Kizumonogatari I: Tekketsu-hen – Oishi’s Story Part 1

Kizumonogatari is as much the story of a vampire and a teenager as it is the story of Tatsuya Oishi. And while his tale is relatively well documented, it’s often tragically overlooked. His impact on SHAFT’s modern state can’t be understated, and yet it’s his comrade Shinbo who stays in the spotlight – the sad yet understandable consequence of what has been happening at the studio for over a decade. To understand this fascinating film we need a grasp of the company’s culture first, so it’s time for some industry trivia.

As of writing this, SHAFT is still celebrating its 40th anniversary, but for a very long time their existence was hardly noticeable. Even their timid attempts at evolving beyond subcontracted work – Eto Ranger (1995) – and recurring collaborations with a powerhouse like Gainax – Mahoromatic (2001), This Ugly Yet Beautiful World (2004) – weren’t enough to make them stand out. And that is why Mitsutoshi Kubota, who took the reins of the studio in 2004 after Hiroshi Wakao’s retirement, planned a revolution. A way to get recognition and ensure economic viability, while increasing their chances to produce their own work. His scheme required a creative leader, and I don’t think the name he chose is going to surprise anyone even vaguely acquainted with the studio: Akiyuki Shinbo.

The director had left a big impression on Kubota back in 2001 through The Soul Taker, which featured one episode co-produced by SHAFT. Interestingly enough, the series also had a notable impact on another famous company; Yasuhiro Takemoto got to direct the two episodes outsourced to Kyoto Animation, and the effect Shinbo had on him can still be appreciated many years later. It’s amusing to consider how a rather forgotten TV show played such a pivotal role shaping the future of two essential studios in the current anime industry.

The task Shinbo received at SHAFT wasn’t simple: he wasn’t going to direct a new series, but rather the whole studio. He became an overall supervisor of their entire output, while also guiding younger artists to make sure this style would live on. This marked the beginning of his unusual moonlighting, juggling jobs in a way that didn’t really allow him to do as much classic directorial work. To date, Shinbo has never been the sole director of a SHAFT series because he can’t. But he didn’t face this crazy challenge all by himself, of course. With his good pals Tatsuya Oishi and Shin Oonuma they formed the appropriately nicknamed Team Shinbo; a group of artists with compatible sensibilities, who had worked together in the past, and shared the desire to construct a new SHAFT.

They were also supported from the sidelines by artists like Nobuyuki Takeuchi, who already had a relationship with SHAFT that truly blossomed once this new period started. Takeuchi started to get credited as Visual Director, a non-standard role that put him somewhere between art&color directors and the role of a series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario., since he also supervised a lot of work and got to draw plenty of storyboards. Shinbo and his companions already displayed clear Osamu Dezaki influences, and by adding Takeuchi – who had worked under Ikuhara a lot as a regular Utena animation director – to the mix, this became even more pronounced. It’s fair to consider Ikuhara and Shinbo to be the most notable heirs of Dezaki’s grandiose staging, so a studio drinking from both streams and full of still young creators willing to experiment was bound to evolve the style in interesting ways. And they did!

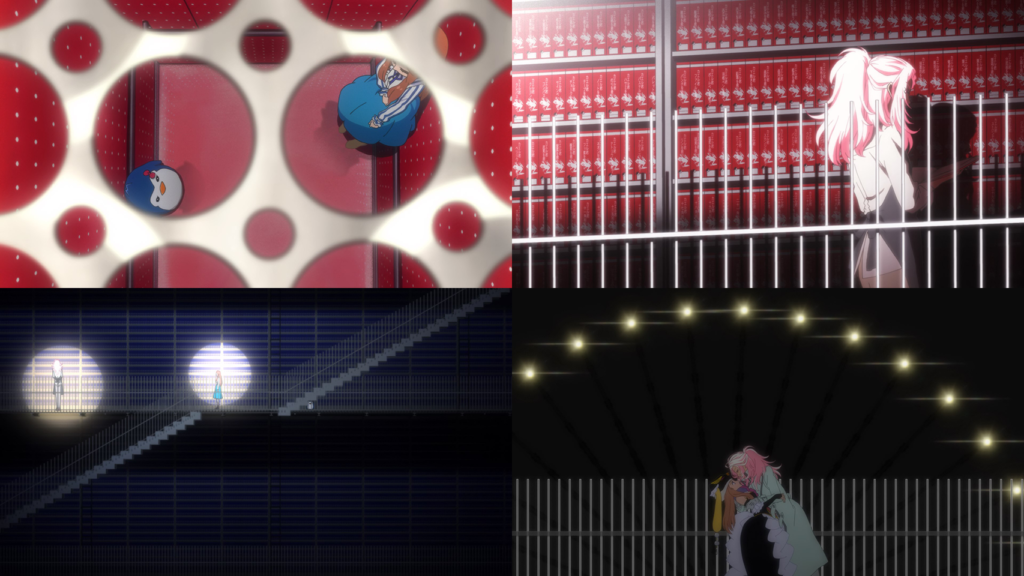

Mawaru Penguindrum #9, directed/storyboarded/supervised/solo key animated by Nobuyuki Takeuchi. A distinct feel of peeking into a stage, noticeable even within an Ikuhara series where framing already resembles a play.

It wasn’t only through the transformation of classic movements that they brought change, though; the studio’s internal structure was rearranged, giving higher priority to the photographyPhotography (撮影, Satsuei): The marriage of elements produced by different departments into a finished picture, involving filtering to make it more harmonious. A name inherited from the past, when cameras were actually used during this process. department while partly abandoning their painting roots. Digital production was still in relative infancy and the industry’s attempts at fancy postprocessing were clumsy, but they weren’t shy on their attempts to use new tech in ways that were innovative back then. While their early output hasn’t necessarily aged well, plenty of filtering techniques that are commonplace nowadays were already used by SHAFT during the mid-00s. This focus on photographyPhotography (撮影, Satsuei): The marriage of elements produced by different departments into a finished picture, involving filtering to make it more harmonious. A name inherited from the past, when cameras were actually used during this process. still lives on nowadays.

Their digital department is actually robust enough to assist other studios sometimes, and the work they do on their own productions is so extensive even viewers without a trained eye tend to notice it. Partly thanks to their infamous TV-to-DVD/Bluray comparisons, which always feature huge differences. SHAFT’s project management has been questionable at best, and falling behind on schedule has become pretty much the norm. That led to some of the last-minute tasks like intricate effects consistently not getting finished in time for the TV broadcast. It isn’t so much that they try to “improve the episodes for the disk release” as many fans believe, but rather that they finally get to finish those scenes as they intended. Even if you prefer the generally less overloaded TV versions, it’s important to understand that those are often simple placeholders they never intended to keep. But I digress!

The beginning of SHAFT’s new era was an exciting adventure. Their first series Tsukuyomi Moon Phase wasn’t that interesting of a work per se, but it became the canvas where the new leaders experimented as they pleased. By the time Pani Poni Dash came out in 2005 they had already found their footing, and pretty much any of their productions from 2006 and onwards could easily be identified by any anime fan, whether they had seen that particular series or not. Through these years they developed a studio culture entirely different from what we’re used to when it comes to latenight anime; having an identity to begin with is rare, as most companies blur into an indistinct mass and their output varies heavily depending on the staff – often freelance – hired for the project.

Modern SHAFT takes it to the opposite extreme. They have a brand. Their godfather supervises every project and oversees the growth of all up-and-coming directors. This ultimately affects even their finances, since most contracts they get are signed under the assumption that they will produce something adhering to the style they’re known for. Some studios stand out from the pack by having a reputation of producing particularly polished work, but in SHAFT’s case, it’s through an aesthetic. A steady source of contracts is the lifeblood of any studio, so having something that immediately sets you apart and makes producers consider you over the dozens upon dozens of other companies is a priceless asset – moreso when it has led to some tremendously successful productions. In this backwards world, standard visuals can be more of an inherent risk. And that means that the uniform SHAFT Style overseen by an always busy yet never truly involved Shinbo is here to stay.

This internal structure differs greatly even from other closely-knit groups in the industry, which don’t have this kind of fixed hierarchy. When Shin Oonuma left to SILVER LINK in 2009 he tried to replicate the system; he also attempted to become a major figure overseeing it all, giving visual cohesion to the studio’s output. However, he eventually had to give up on the idea, instead focusing on his projects alone and no longer imposing a company brand. It seems like no one can be the boss of a studio like Shinbo is. And perhaps it’s better this way, since the downsides to that system couldn’t have become more obvious. Approaches to art evolve as new people give them their personal spin, but they also deteriorate – especially if the replica isn’t natural but rather an unwritten law for the company.

To make matters worse, the people who revolutionized SHAFT barely have direct control on their output nowadays; one had to gradually give up on hands-on work, one simply left, and the last one and his key accomplices spent half a decade pretty much missing – more on him later, since you can probably guess who that is. Without that trio, their idiosyncrasies were stripped of context and nuance, reduced to a checklist of visual gimmicks. Some of their most capable directors like Naoyuki Tatsuwa have the confidence to depart from the asphyxiating guidelines, but even he has uninspired projects churned out of a no longer unique template. And this affects everyone, not just the staff thoroughly bred within the company; even someone like Yuki Yase who was already handling episodes before joining the studio now produces series that fit comfortably within SHAFT’s aesthetic.

This doesn’t mean by any stretch that all series directors at SHAFT are exactly the same – there are decent summaries of their individual approaches – but rather that they’re all subjected to the same restrictions. The fact that some of them manage to produce notable work now and then in spite of that situation is laudable. Having a defined studio culture is fantastic, and as far as I’m concerned their best work is unmistakeably SHAFT, but the current situation is far from ideal.

This isn’t an essay on SHAFT, though. It’s about Kizumonogatari, which is Tatsuya Oishi’s story. And it’s not a sad story, despite being labeled as such. Let’s go back to that early golden age then. Oishi had a humble beginning at Studio Junio, but his capable hands led him to work with Gainax people – with whom still keeps excellent contacts, even nowadays. Through freelancing work he worked on Shinbo’s productions during the 90s multiple times, and it seems like his output on Tenamonya Voyagers finally enamored the person who would become his mentor of sorts. After that his collaborations with Shinbo were plentiful, and he ended up joining his adventure at SHAFT. Oishi shaped the studio and the studio shaped him, a mutually beneficial relationship that boosted his career; he was immediately appointed as a storyboarder, and his architectural sensibilities were quickly acknowledged as well so he began doing all sorts of design work.

It was thanks to his iconic openings sequences that Oishi started garnering attention, though. Editing turned out to be his forte, and his repertoire of imagery – mixing diverse types of media, non-standard transitions, inventive typography, striking use of color – immediately caught everyone’s eye. That made him the perfect candidate to direct these unrestrained yet very tight sequences, which he produced over and over. Looking back on them now, you’ll quickly realize that many of the studio’s most memorable openings like Sayonara Zetsubou Sensei’s OP1, Maria Holic’s intro, and just about every Pani Poni Dash one were directed by him.

And everyone at the studio noticed that, of course. Not only did he become their best-regarded opening director, but as previously mentioned he got also began getting many concept design roles; they even made him Typography Director – no, not a standard job anywhere in this industry – because of his experimentation with text. Isolated pieces weren’t all he did, though. He was also entrusted with storyboards and direction of important episodes, where he put those talents to very effective use, albeit in a more subdued way. Oishi’s work during that time started to quietly define what the SHAFT style has become. He had more apparent triumphs too, as Hidamari Sketch x365 gave him his first chance as assistant series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario.. His work, particularly in the first episode, still stands out as the franchise’s peak, so it’s understandable that he was allowed to properly lead the company’s next big project: Bakemonogatari.

Oishi tackled the idiosyncratic writer Nisioisin with his own peculiar mannerisms, and gave someone similarly unique like Nobuyuki Takeuchi a big role as well. As a mix of creators with that much personality was bound to be polarizing so it’s understandable that so many people were immediately put off by the series, but just as many if not more were drawn to it too. So much so that it ended up becoming obscenely successful, with Oishi’s style catching the eye of people like never before. As a director, his work on the series was the natural evolution of those sensibilities he displayed beforehand – definitely worth looking into, but deserving of a post of its own.

One notable side of Oishii’s work that I feel is too relevant to Kizumonogatari not to mention, though is his affinity with intricate animation, which contrasts with the company’s economic approach. It’s possible that the very root of this is that he was a particularly strong animator himself. His openings managed to put some of those previously mentioned old acquaintances to good use, and his episodes regularly attracted the studio’s best assets. People like Ryo Imamura and Genichiro Abe consistently came to his aid, and eventually became main animators of the projects he was put in charge of. It makes sense that SHAFT’s de facto ace director would have the A-Team at his disposal, but it’s the ambitious scenes that he enjoyed boarding that attracted them to begin with. It’s fair to say that his thoroughness and perfectionism as a project leader perhaps weren’t the best match for a studio with notoriously poor management; a certain Bakemonogatari episode that aired full of placeholders still lives in infamy in famdom memory, but I’d say that things went well nonetheless.

Until that moment, that is.

The unbelievable and yet to be matched late-night success that Bakemonogatari achieved was followed by an unsurprising announcement: the next book would be animated. Of course it woiuld be! Not only that, Kizumonogatari would become a film. But then, silence. For years. Monogatari eventually continued on the hands of other people, yet barely anything was said about the film. The series’ new staff, particularly the director Tomoyuki Itamura, had to fill shoes too big for them. Its execution had to be coherent with the existing material so some elements remained – like the interstitial screens Oishi used – but seamlessly replacing an auteur of his caliber is impossible. It wasn’t until much later in the franchise that Itamura started really feeling comfortable with himself and letting more of his own voice be heard.

Sadly, throughout that period Oishi was nowhere to be seen. It wasn’t just him either, his core team from Bakemonogatari suffered a similar fate. Nobuyuki Takeuchi stopped getting credited altogether, and his name only popped up on some Monogatari production books. Ryo Imamura’s output was reduced drastically. Having the studio aces disappear for years was an unsustainable situation, and the only reasons to remain somewhat optimistic were vague hints. I will make it, fighting on, proclaimed Oishi’s Tanabata wishes. He wanted to, and seemingly he had the staff he needed with him. Kizumonogatari had to exist, as unlikely as it seemed at a first glance.

Overlapping with the overall studio decline only made matters worse. SHAFT’s creative madness was maintained in precarious equilibrium, in an industry where even seemingly solid projects are always at risk of crashing. It is no surprise that a series of unfortunate developments managed to make them stumble so hard. At this point, Shinbo couldn’t really afford to draw basically anything himself. He had become an Ideas person making big structure and key choices, but never responsible for the concrete execution. As mentioned before, Shin Oonuma embarked on a different adventure entirely. And Oishi had vanished. The studio’s new main directors like Yukihiro Miyamoto inherited everything too fast, which didn’t let them properly develop their voices – especially since the company’s partnership with Aniplex made them churn out projects faster than a relatively small studio could afford to.

The layered minimalism current SHAFT productions default to is closer to a watered-down version of Oishi’s style, with the most experimental elements removed. This can’t be stated enough. Perhaps it’s because he had a wider visual vocabulary than his peers. Perhaps it’s simply because it’s easier to isolate his idiosyncrasies, whereas Shinbo’s boards and Oonuma’s digital touch are more inherently personal. This isn’t to say Oishi is all gimmicks of course – I consider him by far the strongest, most deliberate director at the studio – but the truth is that it’s his phantom which currently restricts the directors at the studio. A bit of a shame, since cases like Mamoru Hatakeyama, who left and went on to direct well-regarded series like Showa Genroku Rakugo Shinju at DEEN, prove that the studio is capable of training fascinating new creators.

If only the person who shaped this style could resurface. Run back home and deliver something that actually lived up to the foundations he and his friends built years ago – hey!

I have been repeatedly pointing out that this post is about Kizumonogatari. Which is true, but also very blatantly a lie, as anyone who has made it this far will have noticed. I couldn’t simply jump onto the movie itself, since it’s so fundamentally linked to SHAFT’s developments over the last decade. With all the context out of the way, please join me again for Part 2 of this essay where I’ll actually talk about the film on a very different kind of post. I won’t lie next time, I promise!

Support us on Patreon so that we can keep producing content like this, and move the entirety of Sakugabooru to an independent server. Those who contribute $20 a month or more will also be able to suggest some titles for us to extensively talk about like this!

Just like the monogatari series I was deceived by what was going to be presented to me, and got something different. However I do not find this a bad thing because I do enjoy what you have to say about Shaft. Of course its subjective to whether or not current Shaft is still good or not, there is a great wall that divides the old shaft with the new shaft. Hopefully we get to read more about the style and technical aspect of Kizu. Now we wait for this 3 part series of both Kizu and this write up. I… Read more »

Haha, I really enjoy Monogatari so I allowed myself to have some stylistic fun with this. Even the title is a silly wink to it.

And yeah, the point of this wasn’t to simply say that SHAFT is no longer any good. Monogatari 2nd is easily one of my favorite series they’ve produced, and it was made during that creative drought. I think it’s important that even people who still love their output understand the special way in which the studio functions, how they arrived to that point and who is in charge of what.

Despite Shaft getting a little stale for me (Zaregoto looking just like any other monogatari, but with Yuki Kajiura, on a project that had Take being the original designer) Kizumonogatari was really refreshing and it seems that most of it comes from Oishi going on a different direction from the rest of the studio after Bake.

His work is inherently more exciting than any of their recent output, I can relate to that for sure. Doesn’t mean the rest aren’t capable of putting together a good series, but he has the spark that makes something immediately attractive.

I would really love to see Tatsuwa head up another project. I really enjoyed his work on Koufuku Graffiti, and think he has a lot of potential.

It should be a toss-up between him and Miyamoto to direct the upcoming Fate Extra anime, and he feels more likely if there’s anything significant for Madoka being planned. It doesn’t sound like the kind of series that would play to his strengths, but who knows!

Fascinating read! Before this write-up i honestly thought that the Shaft visual quirks were a result of Shinbo actually directing each series the studio put out – him being credited as a director on every project probably attributed to this. I had no idea there he was more of a supervisor in many cases – guess I’ve been showering praises to the wrong guy all this time! I guess my biggest question is, why didn’t Tatsuya Oishi and his crew go on to director the multiple sequels that Bakemonogatari spawned (or, alternatively, why were they pushed out), and why (and… Read more »

Thanks! My assumption is that Oishi never moved on because he believed in the Kizumonogatari project, but that he struggled *a lot* with it. His approach to the adaptation (which I’ll talk about a lot in the next post) is kind of insane so I can imagine him having to redo the storyboards over and over. Projects that take so long often get axed, but Monogatari being Monogatari means it still made sense to keep on funding it even if it seemed like a hopeless project. Shinbo’s disappearance has been more gradual. He liked drawing storyboards under a pseudonym even… Read more »

Which Madoka episode?

#9, which was officially storyboarded by someone who doesn’t exist.

Absolutely fantastic. I am really enjoying this write up so far.

Its so difficult to find out much about Oishi and reading something this extensive (along with your tweets) really sheds some light on the situation. Hopefully we will see a resurgence of creative strength in SHAFT, or something like that.

More experimental work would be excellent, but I’d be happy to see simply more inspired direction all around. It’s a shame to see a studio with unique and diverse talent succumb to a rigid formula.

Interesting writeup but I think that with skipping Madoka, it appears too arranged that basically Shaft lives and dies with Oishi.

It “skipped” Madoka as much as it skipped every SHAFT production that Oishi wasn’t involved with, because he’s what the writeup focused on. I had to talk about certain shows because they had an impact on him personally and the studio he works at, but basically didn’t mention any of their recent output because he was gone entirely. The series didn’t even have a notable impact on the studio on a creative level (though it obviously was a /huge/ deal considering its success), even the collaborations with Gekidan Inu Curry predate it. Again, don’t take it as “SHAFT has made… Read more »

Looking how many of Shaft’s today “workhorses” were heavily involved in Madoka first. I think it’s quite unfair to try to downplay Madoka for Shaft.

Who exactly?

Was Miyamoto the ‘real’ director behind Madoka? It’s not 100% clear from looking at MAL, etc.

He was the series director, yep. He directed the first and last episodes as well.

Thanks for the fascinating read. I can’t say I’m a big fan of Oishi’s style, but I appreciate how colorful and distinct his stuff is. I’d like to see what he’d do with a straight drama series without otaku-pandering elements.

Which Bakemonogatari episode was the one with placeholders?

Episode 10. If you can find the original broadcast it might be worth watching to see just how many cuts it was missing.