Naoko Yamada: Filmed With The Heart

Today we’ll have a very special post, right in time to celebrate a fantastic director’s birthday – and her entire career while we’re at it.

Last major update: November 2019

NAOKO YAMADA: THE PERSON

Naoko Yamada was born in Kyoto but didn’t get to stay there for long, since she moved to her maternal family’s home in the Gunma prefecture. She was raised in a very rural area before returning to Kyoto years later, something she still fondly jokes about nowadays. Frolicking in the countryside wasn’t her only childhood hobby though, as she recalls already being a fan of various anime; Ghibli films such as Nausicaä were unsurprisingly among her favorites, though it’s series like Crayon Shin-chan and Doraemon that she was particularly fond of – coincidentally, two Shin-Ei Douga franchises with strong connections to the studio that would end up becoming her home. As an elementary schooler, she’d spend time copying drawings from new shows that she came to enjoy, like Dragon Ball and Mobile Police Patlabor. Her artistic interests kept on expanding and brought her to join clubs like the photographyPhotography (撮影, Satsuei): The marriage of elements produced by different departments into a finished picture, involving filtering to make it more harmonious. A name inherited from the past, when cameras were actually used during this process. and tokusatsu ones while growing up, but when it came to academics she settled with something more traditional as she majored in oil painting at the Kyoto University of Art and Design.

While Yamada absorbed the technical knowledge just fine, she had some issues when it came to creating her own pieces. Around the final stages of the course, she felt like she couldn’t properly express herself with the canvas, and instead decided to manufacture a mechanical objet d’art as her graduation project. The struggle to communicate, to convey exactly what she feels, has been a recurring theme throughout her life, eventually becoming a core element in her works as well. In live events and interviews she often notes that it’s hard for her to find the right words to express herself, and various staff who have collaborated with her – voice actors, composers, and the like – have mentioned that she’s never overbearing with precise commands despite having an extremely calculated vision. Rather than risking words to be misunderstood with many orders, she’d rather give them room to perform, correcting their work afterward if need be. In that regard, she’s thankful she ended up in a company where almost all departments and artists are within her arm’s reach, which allows a safe and thorough supervision that isn’t artistically asphyxiating.

It’s worth noting that her interests had drifted rather heavily towards film rather than anime at that point. To this day, Yamada’s still a film buff who uses the company’s staff blog to talk about the directors who convinced her to seek the path of an artist, or even directly influenced her work directing anime; notorious mentions include the likes of Yasujiro Ozu, Alejandro Jodorowsky, Sergei Parajanov, Sofia Coppola, and Lucile Hadžihalilović. It’s easy to draw parallels between their techniques and Yamada’s own titles, but her endless quest to find new ideas (be it from filmmakers or seemingly unrelated fields like mathematics and sociology) to incorporate into her works won’t let us maintain a definitive list of Yamada influences. Perhaps one day she’ll settle down enough so that we can detail all the influences that helped shape her personal ethos, but her constant evolution and general attitude towards the creative process make that impossible right now. And you know what – it’s more interesting this way.

When it comes to animation, the works she looked up to at the time were fairly non-standard as well. She’s not the only idiosyncratic anime director who has cited MushiPro’s groundbreaking, psychosexual piece Belladonna of Sadness as a pivotal experience in her life and constant source of influence. But perhaps more interesting is her choice of Jan Švankmajer’s Alice as the movie that made her pay attention to animation to begin with. This unsettling take on Carroll’s work is a mix of stop motion and live-action footage that hardly resembles anything in the industry she ended up at, and yet it’s the very reason she’s here. Fans are often surprised when finding out where her roots truly are, since a superficial look at her titles can lead you to think that she’s simply a commercial anime director who adores cute things (which she absolutely does!). Observe her work with a keener eye, however, and you’ll notice how tangible those influences can be, even in the most amusingly inconsequential forms.

NAOKO YAMADA: THE ANIMATOR

And so the woman enamored with film, who’d recently finished a university course that somehow combined oil painting with manufacturing of art gadgets, ended up joining a 2D animation studio right away, simply because she saw their leaflet on her campus and it felt right. Considering that she’d already briefly worked at a bakery where she’d used those same artistic skills to decorate cakes, perhaps this chaotic progression was the most fitting end. Naoko Yamada joined Kyoto Animation in 2004 and was first tasked with drawing in-betweensIn-betweens (動画, douga): Essentially filling the gaps left by the key animators and completing the animation. The genga is traced and fully cleaned up if it hadn't been, then the missing frames are drawn following the notes for timing and spacing. for Inuyasha. Back then the studio did lots of outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio. work for other companies, and that happened to include one episode a month of Rumiko Takahashi’s iconic fantasy series, for a total of over 30 by the end of the broadcast. These were almost entirely all handled by Tatsuya Ishihara and the late Shouko Ikeda, whom fans of the studio’s work are surely acquainted with.

This relationship was so beneficial for both parties that KyoAni were even allowed to sneak in the cast of their first original work Munto in one episode, stealthily promoting their biggest project at the time. And amusingly enough, those background characters got more screentime than Yamada herself; due to arriving right at the end of the series and working on episodes where KyoAni only assisted Sunrise and thus didn’t get their in-betweeners properly credited, her name never actually appeared in the series – that means she either made her appearance on #160 or the finale #167, for those of you who appreciate the minutiae. A modest, technically uncredited debut.

Yamada’s own animation on the first K-ON! ending.

Rather than spending a training period drawing in-betweensIn-betweens (動画, douga): Essentially filling the gaps left by the key animators and completing the animation. The genga is traced and fully cleaned up if it hadn't been, then the missing frames are drawn following the notes for timing and spacing. to gain animation dexterity as tends to be the case, Yamada gained trust immediately and started drawing key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. for AIR, where she debuted on episode 9. Anime production is rarely easy, though, so her experience wasn’t as positive as that quick promotion might lead you to think; her first batch of cuts required many retakes, as series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario. Ishihara kindly explained to her. That is a moment she treasures despite the extra work it entailed for her, but most importantly, it marked the beginning of an essential relationship for her career at the studio. Ishihara would proceed to become the mentor of a weird subculture girl throughout the following years, often assisting Yamada when her career was making important leaps.

But it’s not the time for these exciting developments yet: Yamada had to gradually improve as a key animator first. She worked on two episodes of Full Metal Panic! The Second Raid, where she learned a lot from the late Yasuhiro Takemoto despite struggling to keep up with his always demanding pace. During The Melancholy of Suzumiya Haruhi, she got to draw key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. for four episodes instead, and she particularly recalls having fun working on Taichi Ishidate’s inventive layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists. for episode 10. When Kanon (2006) and Lucky Star were in production, her output was already quite high, and regularly included work on climactic episodes. While her career didn’t progress like that of a standard sakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. ace, there was something to her work that quickly caught the eye of her peers at the studio, who made sure to have her around for important moments.

Another sample of her key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. in Nichijou‘s ending.

Going through her achievements as if the milestones themselves were the point while paying no attention to her actual art would do her a disservice, though. Yamada’s drawings can be as refined as you’d expect from someone with her painting career, with a sense of femininity that often stands out. That background is relevant to this day, since painting is still one of her favorite means of expression and a technique she’s managed to give an important role in her works. She defaults to a modern and trendy aesthetic when she’s allowed to draw freely, but bringing out the charm of women is what she enjoys the most – perhaps a bit too much sometimes. Her sense of cuteness isn’t the restrictive perfect beauty anime sometimes has, though; she can convey it with quick sketches, and chooses to do so with very goofy drawings over and over. That everyday, sometimes disheveled appeal is what she always intends to capture as an artist.

Since we’re talking about an animator, though, observing her work in motion is advised. Her timing tends to be on the snappier side, not really abrupt but far from even and smooth, with a pleasant bounciness to it. With the passage of time key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. has understandably become a lesser priority for her; when she acts as episode director she still enjoys drawing rough layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists. and then let animators properly finish the cuts, but as series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario. she has no time for that. This isn’t to say her career as key animator is over, though. Up until the last few years, where she’s been ridiculously busy leading many projects, she was still regularly among the handful of great key animators trusted with ending sequences and studio commercials – my favorite example being the Nichijou ending that was fully key animated by Nao Naitou and her alone, which you can see above. When needed and available, Yamada the animator will always be there.

NAOKO YAMADA: THE EPISODE DIRECTOR

But let’s return to the young Yamada, who’d earned a reputation as a reliable asset by that point. The studio clearly saw more in her than just key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. prowess, however, since in 2007 she was already getting promoted to episode director. After passing the secret director aptitude exam, she went through the ritual of acting as an assistant for veteran staff to ease her way into the new role. First it was under both Ishidate and Ishihara for Clannad episode 8, and then episode 12 alongside Noriko Takao, who’d end up playing becoming a perfect symbiotic partner for her. Episode 17 marked her directorial debut, although she didn’t have room for much personal expression since she was working with Kazuya Sakamoto’s storyboards.

Her first work featured timid attempts at interesting photographyPhotography (撮影, Satsuei): The marriage of elements produced by different departments into a finished picture, involving filtering to make it more harmonious. A name inherited from the past, when cameras were actually used during this process. effects, back when anime’s complex compositing was in its clumsy infancy still, making it a bit of a sign of what would eventually come. The show’s extra episode was her first chance to be fully in control – direction and storyboards – and that turned out to be… a fairly unglamorous debut, to be honest. Decent composition you wouldn’t be able to tell came from an absolute newbie, rather cartoony animation coupled with ridiculous low-angle layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists. to accentuate the comedy, but that’s about it. The entire episode understandably feels like something a pupil of Ishihara would produce, especially when it comes to the approach to the humor. This lines up with Yamada’s animation output as well, which often relied on fish-eye lens distortions and the likes to emphasize that something outrageous is happening in the otherwise everyday scenarios that the studio’s works tend to depict.

The one constant we’ve been coming back to is explosive growth though, so by the time the sequel started airing, she already felt like a different creator. Her involvement with Clannad After Story started with the cute third episode, where her soon to be best animation ally – and already best friend alongside Takao – Yukiko Horiguchi decided to ignore the show’s questionable designs almost entirely in favor of a pleasantly loose and cartoony spectacle, with much more liveliness to it than usual. Yamada got more adventurous with each episode she handled, putting more effort into the lighting, learning to create a sense of space, and trying out new techniques whenever possible; since her mentor Ishihara also happens to be a big fan of photographyPhotography (撮影, Satsuei): The marriage of elements produced by different departments into a finished picture, involving filtering to make it more harmonious. A name inherited from the past, when cameras were actually used during this process., both in real life and when it comes to mimicking its techniques in anime compositing, the series also was the perfect training grounds for someone with a desire to try out new things in that regard.

Not all digital effects have aged well at all, but some striking tricks she’s maintained like dyeing lineart white under light sources already appeared back then. And more importantly than her visual quirks, her direction became tremendously effective. Her episodes turned into a perfect example of execution trumping everything else, as it was hard not to feel engaged even if you weren’t all that invested in the narrative; that’s more generic praise that we can give her direction nowadays, but that’s exactly what she was like at the time: a newbie with tremendous potential who could make memorable episodes, but who didn’t have a well-defined mentality yet. So while that journey of self-discovery had only just started – and arguably isn’t over yet – her peers did notice her aptitude, hence why a newcomer like her ended up co-storyboarding the finale of the first series she was seriously participating in as a director. Serves to say, that’s rather exceptional.

Ever since then, she’s been regularly handling key episodes at the studio, prioritizing her own projects but always helping out others if she’s got the time. Her contributions to series led by her peers are often considered some of the best moments in their respective series, like Hyouka #14, Free! Eternal Summer #12, or Violet Evergarden #5. Even when involved with lesser regarded titles her work tends to catch the critical eye, since studying how she looks at anime is a worthwhile effort in and of itself. Much like how the promotion to episode director didn’t really kill her career as key animator, getting moving up to series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario. hasn’t put an end to her episodes in other people’s series either. But for now, let’s look at how she began leading her own projects.

NAOKO YAMADA: THE SERIES DIRECTORSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario.

While she still had lots of work to do on Clannad After Story, Yamada received a call from her superiors and immediately assumed the worst. She was already doing a fantastic job in a field a newcomer doesn’t belong to, but a creator’s worst critic is always oneself. She lacked confidence and began preparing herself to hear that she’d been fired. When she received the proposal to direct her own series instead, she accepted before even knowing what they were asking her to make. That of course turned out to be K-ON!, her personal paradigm shift. Despite working with source material limitations that made it hard for her new writing partner Reiko Yoshida to properly structure the series, the show ended up towering above its peers – in popularity, technical accomplishments, and raw heart.

It’s at this point where Yamada’s method direction, which she tried to apply to her individual episodes previously, finally blossomed. She always obsesses about every character’s demeanor, insisting on treating them as autonomous entities rather than pawns that she could have full control over as a godly creative figure. Yamada’s expressed that she’d rather become an invisible director without an apparent style – tough luck on that, I’m afraid – than eclipse the people who happen to live in her stories. Her anime becomes beautiful almost by accident, since from this point onward she heavily prioritizes expression over leaving an impression, the feelings of the characters as something more important than even the clarity with which they’re transmitted. In a way, Yamada’s anime is directed by its own cast.

The team captured the essence of high school life so precisely that the series managed to trigger a powerful and sweet sense of nostalgia, even if the events depicted weren’t something you experienced yourself. Yamada and her team constructed a club where friends mostly laze around and made it become a familiar and warm place throughout the series. This immense relatability ended up turning a niche manga into an unexpected monstrous hit. And leaving aside its incredible financial success, the most significative sign of its popularity was the virtually unmatched mainstream appeal for a modern latenight property aimed at men; K-ON! managed to attract larger audiences of non-anime watchers and women than shows perceived as way more approachable in the west like Madoka Magica. Its eventual broadcasts on important TV blocks aimed at children and teens should come as no surprise then, but they were exceptional nonetheless. It also had a big effect on the wave of latenight series chasing this dream by putting a group of girls in a random school club, though none came close to matching it.

Its brilliant accomplishments don’t hide the series’ shortcomings, though. As a newbie director, Yamada was afraid to stray too far from the frankly unremarkable source material, and instead used original content to elevate it rather than making something that was truly of her own. Yamada also struggled to juggle her own episodes with the larger picture; as the series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario., she had many more tasks to do than when handling one episode at a time, making her own storyboards less impactful than usual. Instead, it was people like Takao who delivered the most memorable episodes. The person who’d coached Yamada when she was getting promoted went on to become one of her most powerful weapons in this series and its sequel, even causing her to adopt some traits like the moody ambient lighting. Some rumors fueled by an ex-member of the studio suggest that Takao’s departure after the second season of K-ON! was due to feeling overwhelmed by her friend’s powerful irruption, but even if that were true, in the end they had a positive effect on each other and both went on to direct beloved series.

While the evolution of Yamada’s personal style was more moderate compared to the previous giant leaps, K-ON! finally gave her a proper venue for certain aesthetic sensibilities. The trendy music video approach to the TV show’s ending sequence didn’t only become a recurring custom for the franchise, it’s stayed as a personal quirk that leaks into her other works. But if we’re going to talk about an artist personally using the series as a launching platform, it has to be Yukiko Horiguchi; whatever your aesthetic preferences may be, it’s hard to deny that hers are perfect animation designs, malleable forms that lend themselves to nothing but charming drawings. And yet this isn’t at odds with detail: all her works have gone on to feature intricate shots that feel right at home, and her design sheets include so much information about how the characters look and act that all animators who work under her are delighted to do so.

Every loose sequence in K-ON! is a delight – even if it’s just 4 frames – but those designs also enable excellent pieces of animation that aren’t based on extreme exaggeration. These are the designs that made renowned animators like Toshifumi Akai and sushio fall in love with Horiguchi, and the reason why even when she quit animation she still attracted artists like One-Punch Man’s Chikashi Kubota. It says a lot that her recent jump into Twitter under a pseudonym was kind of an anime industry event, and how her gradual return into anime via the 22/7 commercials has many sakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. aces who never got to work with her when she was exclusively working with KyoAni dying to jump into any of her new projects.

Most 22/7 short films draw not just from Horiguchi’s direct input, but from Yamada’s school of direction as well.

The most positive impact of all K-ON‘s recognition might have been how it boosted Yamada’s confidence before season 2, something she has personally admitted in interviews. Even if you’re harsh on yourself, a hit of that dimension has to be a big morale boost. Her reinforced spirit, alongside way better planning, paved the way for a strong sequel; this time around they had twice as many episodes and no new core characters to rush to introduce, so they focused on depicting the last year of the club members’ highschool life at a leisure, natural pace. And with one episode alone, that approach put the original series to shame. The change in atmosphere was unbelievable considering that the first season wasn’t exactly set in an inert school backdrop to begin with, and far from being a fluke for the intro, it ended up setting the tone for the whole season… though admittedly, this time Yamada did stand atop every other episode director, so the palpable atmosphere in her first episode was rarely ever matched.

The Houkago Tea Time girls left the clubroom constraining them just like the staff broke the chains of the source material weighing them down, expanding the K-ON! universe on many levels. Recurring classmates quietly came alive, the more diverse locations and slow but sure passage of seasons enabled a gorgeous variety of lighting and moods, and the setting as a whole breathed in subtle ways like the club’s board. Ever since the first season it changed on a weekly basis, with new drawings and comments based off recent in-universe events. And, following the general trend of taking the solid concepts present in the first series and going wild with them, season 2 took that commitment to off-camera life and went as far as adding new scribbles within the same episode to represent the passage of days. Yamada’s thoroughness in making the school feel real through details like that is commendable. She firmly believed that K-ON! was deeply rooted in realism, though I feel her sense of real is more along the lines of imbued with life than strictly representative of the world, because K-ON!! is still a cartoon and proud of it. Though considering she spent hours upon hours arguing with Horiguchi about the exact proportions of the cast, perhaps there were some concerns about actual realism as well.

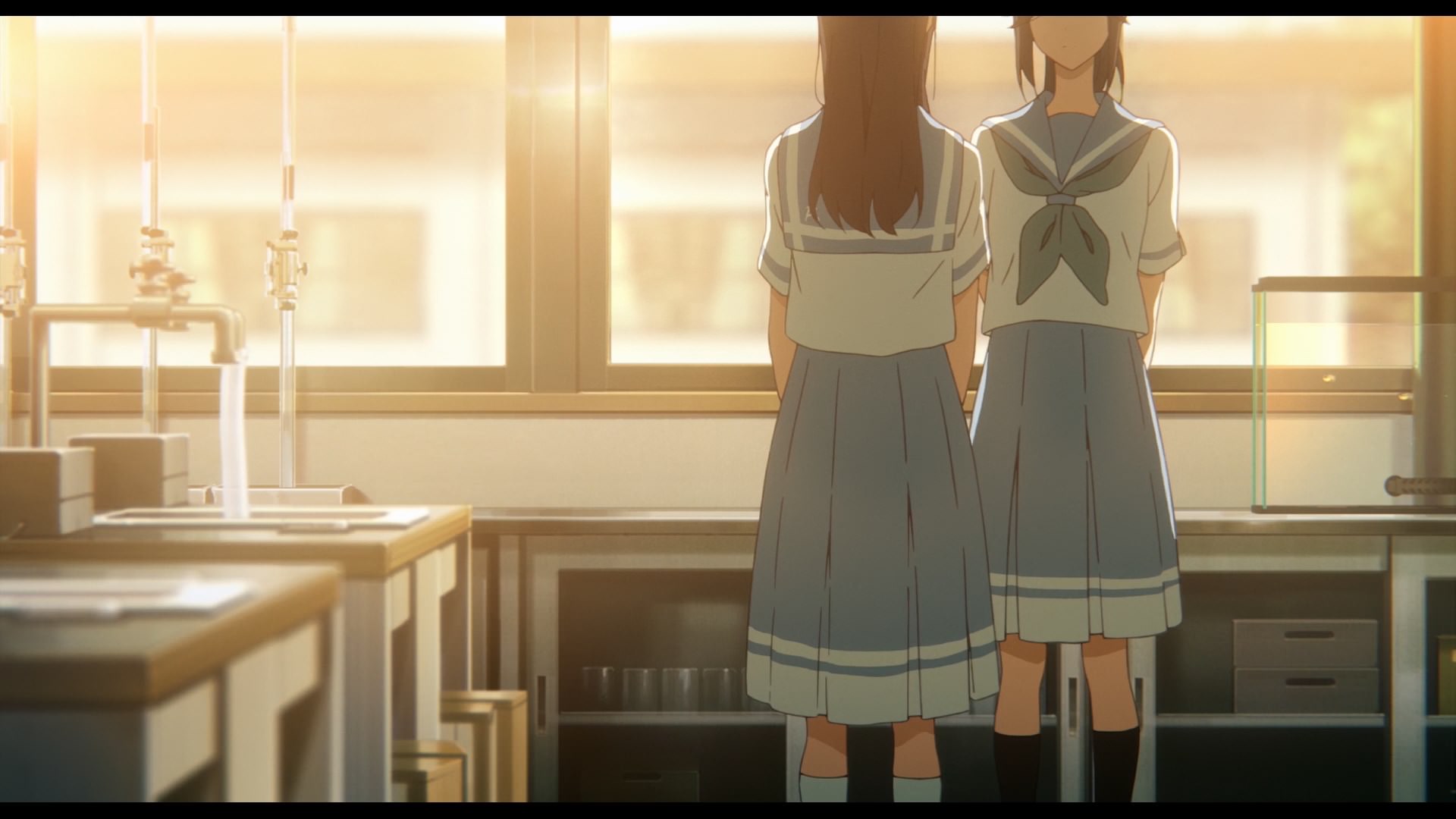

With that adjustment of the atmosphere came an adjustment of the aesthetic. The designs lost a bit of elasticity, but the characters gained enough visual personality to make up for that. Yamada’s attention to gesture and the increased length of the series allowed them to build a true acting vocabulary for the cast, consistent and ever-expanding. While as a director she has amusing recurring postures, her understanding of body language always comes first. She approaches her own life with this attitude, paying attention to these mundane events that actually spell out who we are. This was accompanied by more nuanced framing, as she finally mastered some tricks that are integral to her modern work like the leg shots as a window of the soul – not as glamorous as eyes, but equally effective in her hands. Far from being a silly quirk, she’ll go as far as to conclude a film with an obscenely expressive long sequence that focuses almost entirely on the characters’ legs. The consistent level of excellence they achieved led to an animation legend like Toshiyuki Inoue to call it the perfect TV anime, while heavily praising the studio’s work. They crafted something truly special, even by KyoAni’s high standards.

There was another budding tendency in the fantastic second season, but it wasn’t until the movie that Yamada really started focusing on the idea of anime as footage to be filmed. Very aware that many people would watch the movie on a big screen, Yamada carefully constructed the layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists. (assisted by the studio’s godfather, the late Yoshiji Kigami) with that in mind. since the very beginning of her directional career, Yamada had been toying with the idea of simulated lenses, but from this point onwards she would start thinking about anime’s actual camera. The effects she wants the team to apply may be what people notice the most, but the way she conceptualizes shots keeping in mind not just what’s happening but how it’ll be consumed is what makes this approach work. The K-ON! movie began extending this level of carefulness to other aspects as well; the expanded range of color – as they were capable of adjusting light effects on a per cut basis when necessary, rather than the show’s already thorough per scene basis – and the relentless animation display truly made it feel like a theatrical production. Following franchise traditions, it proceeded to absolutely smash all records at the time, paving the way for the currently booming latenight anime film market.

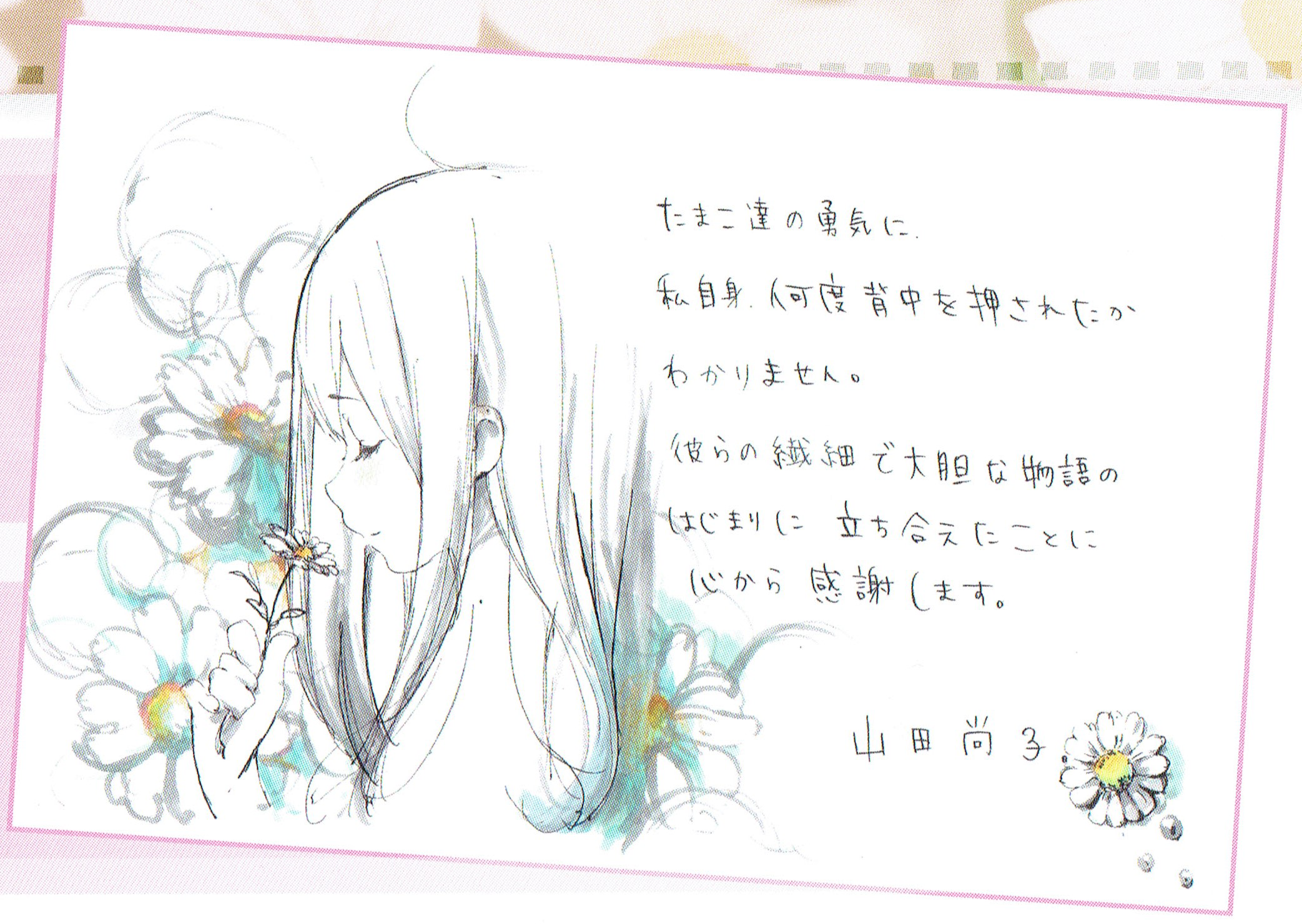

When a franchise lands nothing but historic hits, then chances are it’ll never go away… and Yamada & co actually rejected the proposal of a third season of K-ON! in favor of an original project that eventually became Tamako Market. This charming little show felt like a natural follow-up to the way the second season of K-ON! turned the setting into as much of a character as the main cast. The titular market was populated by colorful people and shops, living up to its promise in that regard. The episodic tales showing the different shapes love can take contained isolated greatness, while generally remaining a joyful experience. Unfortunately, the show was brought down by a half-baked final arc that felt like detritus from scrapped, more narrative-focused plans, and poor timing didn’t allow it to be up there with her previous outstanding productions. With no commercial success either, it seemed like this would be her first failed adventure.

All things considered, that only makes Tamako Love Story’s existence all the more satisfying. The unlikely sequel film took ideas casually tossed around but never properly examined by the original series and did an outstanding job with them. The lens turned inwards, and this time the tale of love being explored involved the protagonist and her childhood friend, who weren’t very compelling individuals in the original series – and yet it worked tremendously well! A bittersweet movie with an extra serving of the sweet romance part, but also a fantastic articulation of adolescent worries. If Yamada the storyboarder reached her maturity halfway through K-ON!, then Yamada the film-maker began doing so with this movie. Her visual lexicon was fully established, from her love of bokeh and telephoto lenses on a compositing level to the very look of the serene skies. She exploited live-action techniques while enjoying the inherent freedom of animation, which is the core of her modern approach and what makes her storyboarding and direction so unique.

And speaking of her boarding prowess, it’s worth noting that she handled the entire film all by herself. Considering she also storyboarded ¾ acts for K-ON!’s film, the vast majority of Koe no Katachi, and the entirety of Liz and the Blue Bird again, her desire to be a very hands-on director is undeniable. And seeing how effusive the judges that awarded her with Japan Media Arts Festival’ New Face Award were after Tamako Love Story came out, going the extra mile like that was well worth the effort. Was there room for more growth, though? People all around the industry have been reacting with heavy praise to everything she’s been doing for a while, specifically pointing out her peerless, delicate technical direction; as Makoto Shinkai put it, it’s a refined and noble style that you want to copy but simply can’t. Is being a very well-regarded film director as far as her influence extends then?

NAOKO YAMADA: THE STUDIO AND INDUSTRY LEADER

Summarizing a complex series of events by singling out individuals is reductionist, but it’s fair to say that Kigami shaped Kyoto Animation up to the point it started becoming a notorious independent force. While Takemoto’s work is much more to my personal taste, it’s Ishihara who then followed up and became the most influential creative figure at the studio on their rise to fame during the second half of the decade. These eras are relative, of course. Boundaries aren’t strictly defined and it’s not as if these figures eclipsed all other directors, but they definitely were the dominant voices at some point. And yet it seems obvious that the climate at the studio changed yet again. Ishihara’s been succeeded by Yamada, the eccentric newbie whom he once coached. The symbolic baton pass arguably occurred as early as around K-ON!’s end, though its effects only truly became apparent after productions like Tamako. As I said earlier though, I believe that there’s little point to perfectly delimiting these eras, and would rather focus on observing their peculiarities.

What does Yamada’s leadership entail then? On an individual level it means that she’s earned a special place at the studio, with enough weight to claim a project as important as Koe no Katachi despite not having read it yet when the deal was sealed. But you’re not a leader without followers, and that’s where this gets interesting. When it comes to KyoAni’s new generations of young directors, Yamada is far and away the biggest influence. Shows like Euphonium, where she supervised everyone’s work rather directly as series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario., only made this even more obvious. The studio’s new hope Haruka Fujita is a strong candidate to inherit her delicate touch, and has been learning from her as she acts as her substitute of sorts when Yamada is too busy. Even a director like Taichi Ogawa who was someone else’s pupil got eventually pulled in by her gravitational force, and with time he’s become an anime cameraman just like her. Even after his tragic passing, Kigami will remain the figure that the studio’s key animators ook up to, but when it comes to directors, there’s a new icon to follow.

Another aspect in which Yamada’s presence seems to have had an effect on the studio as a whole is the company’s gender ratio. Both the fact that anime is still a male-dominated industry and that Kyoto Animation is mostly composed of women are rather well know pieces of information. The latter is something she was hardly responsible for, of course; she estimated that back when she joined the company was already around 60:40 female, which should be understandable on a studio where the person with the ultimate choice over everything that gets animated is the woman who co-founded it. The industry as a whole is thankfully – albeit slowly, as these things go – moving towards at least a healthier parity, so with time we might get more spaces like KyoAni where women consistently command the creative process, rather than only having isolated projects where they do. Rather than simply going with this flow though, the studio’s gender gap is widening faster than ever. For the last handful of years, all new key animators promoted at the studio had been women – a rather significant data point for a company where only animators are given main roles in production. While KyoAni is clearly in need of thorough rebuilding at the moment, it seems very unlikely that those trends will change.

Yamada was their first female series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario., which paved the way for more, and her open desire to work with women by her side must have had an effect on promotions for the last few years. She’s particularly adamant about women acting as animation directors when possible, both within episodes and as character designers and chief supervisors. Versatility is required as an animator and she clearly doesn’t think that gender is a be-all-end-all (after all, the late Futoshi Nishiya formed a tremendous duo with her in Koe no Katachi and Liz and the Blue Bird), but she hasn’t hidden that she prefers to rely on female artists when it comes to articulating the behavior of women within animation. And it’s not just on a visual level that she favors women: her scriptwriting buddy Reiko Yoshida has been in charge of all of her projects, and Yamada’s openly admitted that she values her work amongst many other reasons due to her female POV, which “deals with certain situations in ways men wouldn’t dare to or even be capable of.”

Her next film Koe no Katachi, however, proved to the audience – and to herself – that those preferences weren’t actually a deal-breaker. As someone who struggles with communication even if to a much smaller degree, the movie felt like the most natural progression for her, but it also was a first in some ways; Yamada admitted that she was worried she wouldn’t know what to do with her first male protagonist, which also happened to be her first project where the key staff wasn’t fully composed of women. A big change… or was it? Yamada was delighted with the exquisite expression in Nishiya’s designs and animation, and has since then said that her worries about dealing with a male protagonist were simply misplaced. As a director who respects her characters as individuals, she realized that her portrayal didn’t rely on gendered tendencies to begin with, so that was just a superficial difference. As it turns out: gender, kind of an arbitrary thing.

This isn’t to downplay her role in the current positive trends at the studio, though. Her modus operandi often involves carefully, almost obsessively, depicting female characters. This can resonate very strongly with women, hence why to the surprise of some people, the biggest demographic when it came to Koe no Katachi‘s attendees in Japan ended up being female teenagers. And if they fall for her works so hard they decide to join the studio, chances are that they’ll be taken under her wing as well. Despite being in separate branches at the studio at the time, Free! and Banana Fish‘s director Hiroko Utsumi looked up to Yamada as a friend and mentor of sorts; she debuted as storyboarder and episode director in K-ON!, and later relied on her for advice and to direct the OP/ED sequences when she received her first chance to lead a project. And while Utsumi left years ago, her series’ popularity made dozens upon dozens of young women aim at a professional career at KyoAni – which a bunch of them have managed, receiving the opportunity to learn from Yamada and perpetuating that cycle.

Don’t get me wrong: I don’t think this is something that she’s consciously doing, and it should by no means be interpreted as a progressive revolution that she’s been planning for years. But she has had tangible positive effects on an industry that still needs more women in key roles. Understating her impact at this point would be foolish.

What comes next, then? Her evolution as a filmmaker clearly hasn’t stopped: Koe no Katachi was a landmark in tactility within Japanese animation, a major point in a movie where communication has an inherent physical component, while also starting her partnership with composer Kensuke Ushio. The fascinating soundscape of the film was taken to another level entirely for Yamada’s latest film Liz and the Blue Bird, which fundamentally challenges standard production methods by intertwining animation and sound in a way that commercial anime had never seen before. That, alongside new tricks she had up her sleeve (like the audiovisual decalcomania that’s meant to mirror the similar yet never equal lives of the two main characters) makes both her last movies tremendous technical and emotive achievements that we’ll have to explore at length in separate articles.

Yamada heading new works is an exciting event in and of itself. Even if the narrative doesn’t sound that compelling, that simple, sincere core surrounded by an obscenely detailed depiction of life sprinkled with avant-garde techniques is something you know you can look forward to. But I’d argue that the last stage of her career isn’t defined by her growth as a creator, as that’s actually been a steady process. What’s truly changed in recent years is how, in the same way that she’d been influencing up-and-coming artists at her studio, that’s now happening for the industry at large. Though she was already used to receiving praise by renowned individuals, I believe that the difference is made when youngsters burst into the industry holding someone as their idol. Recurring SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog protagonist ちな, one of the most precocious stars in anime history, recently admitted in an interview that it’s Yamada whom he looks up to the most and the one whose vision he tries to mimic when directing… surprising no one, as that’s amusingly obvious in his stunning episodes.

Of course, he’s just one of the many artists we could point at to represent this new generation of artists with a thick layer of Yamada influence all over their work. Shin Wakabayashi, the promising young mind behind the aforementioned 22/7 short films, is another brilliant example of this phenomenon; the entire short series appears to use K-ON!! as its holy scripture, balancing Horiguchi’s cartoony charm with Yamada-style method direction. The presence of creators like them is spreading that Yamada flair further into A-1/CloverWorks territory… even more than it already was, since her old partner Takao was already one of the studio’s aces. Even if you take it to different fields you find cases like Fukkun, a composite artist in-between the indie space and the professional industry, who keeps studying Yamada’s approach to direction and lighting work in an effort to grasp the style that fascinates him so much. As weirdly specific as her appeal can be, once her magic captures you then you might as well giving up hope of ever escaping, hence why it’s fairly easy to find up-and-coming artists with tangible Yamada influence.

And that is one of the small sources of hope in the studio’s tragic situation, after the arson attack that took many employees’ lives and hurt the hearts of even more. KyoAni is in the midst of a process of healing and rebuilding, having recently opened its doors to animation students as they normally would, but with a new feeling of urgency that can be felt in their application guidelines. More than ever, KyoAni needs inspirational figures who can attract young prospects to the studio and are then capable of mentoring them if they join the team properly – exactly what she has been doing over the last few years. It might take much longer than expected to see Yamada’s next work, but in these circumstances, I can only be glad that the studio has her around. Happy birthday, パピコ.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

Happy 32nd Birthday, Naoko Yamada.

Also, this was a really great post. I didn’t know some of the things about her that you posted.

Awesome write-up about my favorite director! Happy birthday 山田!

Excellent article for a truly exceptional artist! Congratulations, director Yamada!

Thanks for this! What a fantastic read. I love Nichijou, and I’m forever thankful for Yamada’s dedication.

She actually loves Nichijou so much she still has a bunch of Nichijou merch around her desk. Seems to be a favorite around the studio.

NAOKO YAMADA: THE QUEEN OF THE WORLD

seems like the natural progression.

Only benefits from being the best you can be, this post tells me!

Indeed, what she says about the feet/legs. The sequence you shared of the K-On film is sentimental because of that kind of cut and balance, where you know whats going on up there but it`s enough to express down there. Ah, what am I trying to say?

Thanks for writing!

rereading this article now i realize that yamada’s approach to animating life in a way that FEELS real and believable rather than being 1:1 accurate to reality sort of reminds me of takahata’s work with ghibli. her work is more whimsical and sensory than his in ways but the intent feels similar. i look up to her and her proteges so much as an artist, and having these detailed profiles of animators and directors is so helpful and informative for anyone looking to dip their toe into sakuga culture–so thank you so much for all your hard work!!!!! (and happy… Read more »

The link between them might seem tenuous but it’s actually very direct – Kigami was fascinated by Takahata’s approach on Fireflies, and he rebuilt KyoAni following that. It’s no surprise that they share similar fastidiousness and even that desire to challenge how anime’s made since at the end of the day, they share the same core philosophy.

“But she has had tangible positive effects on an industry that still needs more women in key roles. Understating her impact at this point would be foolish.” Yamada is truly one of my most favorite people in the anime industry, and I consider her, along with Mari Okada, to be impressive examples of female talent, but I don’t think the word “need” is appropriate enough. It sounds like studios should hire someone just because of their gender, and not according to their talents. At the same time, I believe that the examples of Yamada and Okada are impressive enough for… Read more »