Anime Craft Weekly #29: Major Mainstream Misunderstanding – Part 2

On the first part of this essay I addressed some common misconceptions about anime widely enjoyed by general audiences; first regarding misguided attitudes like mainstream acceptance being related to excellence and artistic intent, but also important facts like the existence of huge family series invisible in online discourse. And perhaps more relevant to people’s interest, a sample of latenight shows that managed to reach non-anime fans, which proved that the assumed biases against common aesthetics and premises are massively exaggerated by the western community. For many years, television has been the vehicle through which all sorts of anime has arrived to many audiences beyond what English-speaking fans and other subcommunities outside Asia tend to assume. But there’s a slight issue – TV is dying.

That is far from a problem exclusive to anime of course, since the decline of television is a worldwide phenomenon caused by the eruption of new and more efficient ways to consume media. Since audiences for animation content skew younger than for live action material though, this industry has received the impact with full force. Understanding the situation prior to this media revolution is important, but I don’t feel like this is the right time for an extensive overview of anime’s history; it has existed in TV series form for over 5 decades after all, and even the first latenight broadcast can be traced back to the 60s. The major point you should be aware of when it comes to the issues we’re dealing with is that for the longest time, TV channels themselves financed lots of anime. They were still a driving force when anime majorly moved to latenight shows that make monetization through advertisements trickier, and even as the industry’s output skyrocketed aided by digitalization. When the usage of wide production committees (where a bunch of companies split the costs and thus the risk) became the norm, TV stations were a very consistent source of funds. Daytime shows with big live audiences could reach lots of people through the ads intercalated with the broadcast, and latenight series at the very least managed to promote themselves alongside some other properties owned by the companies who funded the project. It’s easy to see why channels were interested in anime, particularly adaptations of already popular material.

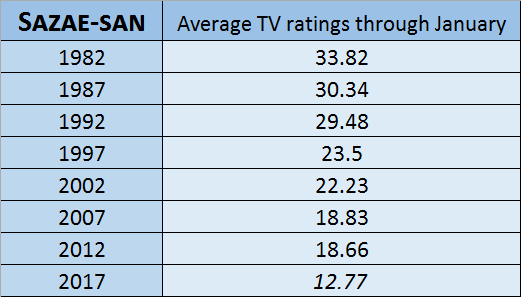

I was talking in past sense for a reason, though. Animation has always had a bit of a hard time competing against live action, which is comparatively less expensive and reaches more people; while it’s not a widespread idea, there is a sizeable number of people who simply won’t watch any animated material, whereas no one would seriously be against consuming media with real people. In spite of that, there were still a bunch of shows with absolutely mind-boggling viewerships – the Top 10 TV anime ratings is almost entirely over 30%. You might recognize the top two there, because they happen to be those family shows that I mentioned last time since they still carry on strongly nowadays. But while Chibi Maruko-chan peaked with its 39.9% during one week in 1990, nowadays it struggles to reach 10%. Ratings in general have decreased due to the increasing number of options, but anime in particular has decayed rather extremely. Since Sazae-san is still comfortably ahead of any other anime, let’s see its evolution throughout the years by comparing January ratings.

There are multiple factors at play here – the aforementioned general downtrend of ratings due to more and more options being available, as well as the tendency of long-running programs to decay after a while. That said, the decline is so steep that it tells us this is no ordinary situation. And if you thought that’s bad, let’s look at how modern Gundam series have fared, since that highlights a specific issue.

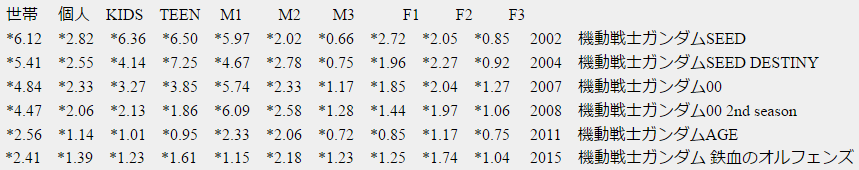

As you can see the general viewership keeps declining, but young people in particular have vanished. Even Iron Blooded Orphans, with which Bandai explicitly wanted to recapture those younger viewers, barely recovered from AGE’s disaster. And if you wonder if that has an actual impact on anime – damn right it does! The Nichigo timeslot, which has been one of the main avenues for daytime anime, will die after Iron Blooded Orphans’ second season ends. It has been unceremoniously fulminated, and we have enough hints to determine the decision was taken not that long ago. The first teaser of My Hero Academia’s sequel back in June 2016 featured MBS’ name, which seemed perfectly natural at the time. The TV station had partly funded the series after all, hoping it would do well and boost Nichigo’s ratings. And yet they vanished from the next promotional videos, even before it was announced that the second season would actually move to the rival network ytv/NTV. It seems like the sequel was initially planned to air on Nichigo again, but its untimely death forced it to move elsewhere. The irony of the situation is that My Hero Academia’s cache has allowed it to land on an even more popular timeslot, so it has actually benefited from these unfortunate developments. MBS/TBS’ reaction has been to replace that Nichigo slot – 5pm on Sundays, as its name indicates – with an expanded block for anime starting at 6:30am on Saturdays. The reasoning is transparent. They understand that it’s not as if teenagers are less likely to become big fans of anime nowadays, all that’s changed is the way they choose to consume it; tablets and phones are extremely common amongst teens, but not so much with infants. And since as a TV channel it’s more complicated to monetize series being consumed through other avenues, they decided to chase the latter group. That’s why the shows that are being announced for this not-quite-successor of Nichigo are blatantly aimed at younger crowds.

It might seem like I’m painting a dark future here, but doomsaying isn’t the objective of this post. We recently featured an analysis of the industry’s yearly growth, and those relatively positive results already indicated that if anime falls apart it won’t be because of a lack of interest and potential customers. Television might be dying for real, but it’s not going to drag anime down with it. As much as corporations love a profitable status quo, they’ll be forced to change if profits depend on it. To be honest, it’s always tricky to predict future developments regarding an industry like this, barely held together by elements in precarious balance. Having arrived to this point though, it’s more of a matter of observing the present than speculating about the future, since those changes are already happening. Online distribution will be the first thing that comes to mind for most people, and for good reason. The number of productions openly aimed at a worldwide audience is increasing thanks to it, but even projects manufactured with Japanese people in mind see it as a perfectly valid avenue. Many people don’t seem to be aware of the existence of Monster Strike, yet that phone game is so massive it earned $1.3 billion in 2016 alone. Adapting such property into anime would be quite a big deal, and when it came to it they decided to go with Youtube as the platform. That worked out quite well, with hundreds of millions of views through its entire run – as you can see, the first episode is sitting at over 4 million views. It eventually received a movie as well, once again proving that TV isn’t really needed anymore.

That reflects another change we’re starting to experience, the new opportunities in the theatrical space. There were some exceptions like Ghibli and Mamoru Hosoda’s output, but for a long time the vast majority of hugely successful anime movies were spinoffs of existing TV properties. You might think that Ghibli’s disappearance would be a fatal blow to this already limited outlet, but it appears to have had the opposite effect. Makoto Shinkai’s Your Name has absolutely wrecked right about every other original anime film, and the continued success of A Silent Voice and In This Corner of the World are a sign that adaptations no longer need the support of television either. The latter struggled to even exist, with multiple delays and crowdfunding campaigns, yet despite its painfully mediocre initial earnings it’s been carried by excellent word of mouth into big success. And while that enamored older audiences, A Silent Voice became a sensation amongst teenagers, especially girls. It was the first time the studio produced a film not tied to an existing show, and despite their hesitation it turned out to be their biggest hit of all time. The success of those three 2016 films amongst different publics will only encourage other companies to attempt similar endeavors. Even someone whose work is so inherently niche as Masaaki Yuasa has managed to get TOHO to distribute two new films of his this spring – if that doesn’t make you hopeful about the future of this medium, I don’t know what will! As you can see, the evolution of the industry reshapes the concept of mainstream anime as well. There will continue to be anime that reaches people beyond latenight otaku, all that will change is the delivery method.

That was a lot of words about mainstream anime between these two articles! I hope I didn’t make everyone’s brains melt halfway through.

Support us on Patreon for more analysis, translations, staff insight and industry news, and so that we can keep affording the increasing costs of this adventure. Thanks to everyone who’s allowed us to keep on expanding the site’s scope!

MonStrike getting the recognition it deserves. Youtube is great for it and it was wonderful. I wish it had regular runtime though instead of 12 minutes, though I do like the extra time sometimes for more promo of White Ash, who now I see as the face of Monster Strike.

How is BNP success with their kids animes (TriCool, Brave Beats, Heybot, and I guess DreamFes)

More stand alone anime films!? Yes, please! I’ve always found original, or stand-alone, movies to be the very best way to get new people into anime. They are easy to consume and usually conclusive, so all I need is to get someone to sit down for 2 hours or less and proceed to be sold! I’m also just generally a fan of films for some of the same reasons. A good somewhat complete story in one sitting is very satisfying. And the production schedule of films is, of course, generally much better than TV series, and allows for a lot… Read more »

That’s actually an interesting point! With the industry moving towards films big time, services like Crunchyroll will have to find new ways to stay competitive and that won’t be easy. Acessibility could become temporarily trickier.

That’s certainly the downside of movies. I guess streaming doesn’t work quite the same for them, unfortunately. I don’t know if that’s just because of the perception that Japanese companies have that streaming is really only for TV series, or if there is a legitimate financial reason that streaming doesn’t work as well for movies. Either way, hopefully something works out. I see them in theaters when I can, but that’s about as much as I can do at the moment.