Studio Culture In The Anime Industry – The Curious Story Of Free! And High Speed!

Fans and critics alike love to associate qualities and flaws to anime studios, but to which extent does that hold any water? Have companies managed to build an in-house style of their own, and do they want to do that in the first place? We’d like to address misconceptions in this regard while explaining the potential of studio culture in the anime industry, as illustrated by the very curious tale of one of the biggest anime series of recent times: Free!.

For the longest time, the anime fandom has had a studio-centric view of the world of anime. It’s slowly changing as of late since it’s become easier for viewers with an interest in the inner workings of the industry to find out about the massive degree to which freelancing affects anime production, but I’m under no delusion that we’ll ever get to a point where anime fans will mainly look at key staff rather than the studio they’re momentarily attached to. As misguided as it is, that mindset does make a lot of sense; it’s much easier to track studios than individuals, there’s the belief that this is exactly how it works in other creative spaces (whether that’s true or not), and critics perhaps don’t have the best track record of pointing out how anime is actually made. Add all those up and the misunderstanding of the nature of the industry becomes chronic.

With that in mind, the irony of the situation comes from the fact that many studio leaders would love it if those misconceptions were true at all. Anime production companies are for the most part desperate to pick up as many contracts as possible because each project by itself won’t even serve to keep the studio running for as long as they have to work on it. They need to fill up their schedules, and doing that means wrestling with the countless other studios that are in similarly tight situations. If they haven’t managed to earn a reputation as hit-makers or as an animation powerhouse, establishing a brand of sorts can at the very least help them stand out a bit more. It can serve as a bargaining tool when negotiating and gain them more offers in the first place. This can end up entirely defining the identity of a studio, as seen with studio SHAFT’s revolution and the direction they’ve stuck to ever since.

Have they succeeded at large, then? The answer is obviously not. A massive percentage of anime production companies continue being flavorless, often simply being a set of hired hands without a noticeable personality they adhere to. Perfectly capable of making memorable work, of course, but without much cohesion besides tenuous links for fans to take out of proportion. At the end of the day, a studio’s identity is defined by nothing more than their practices, the creators attached to them, and their output. That means that if they aren’t able to maintain a company ethos, all that’s left is staff that tends to come and go and a series of projects that often correspond more to availability and personal connections than a desire to chase certain genres or aesthetics.

But of course, as much as that’s true in the general sense, there are multiple exceptions. A few companies have identities of their own, which impacts their work to different degrees depending on how prevalent and consistent it is. Some producers and directors manage to get the very specific kind of anime they want to make funded – everyone knows what TRIGGER’s core team is fond of – while others limit it to a subset of their output, like P.A. Works’ working anime tradition. That personality can also come from recurring staff members eventually dyeing the company their own color; though freelancing is the number one defining aspect of the anime industry, the next key aspect is interpersonal relationships, which can create situations where key staff return over and over to the same studio – if the bond is strong enough and they have a bold style, that can also give the company its unique flair. That also includes relationships with companies, like the link between studio ufotable and Bandai that’s led to the former’s involvement in many video-game adaptations, simply because that’s the latter’s business.

As you can see, developing a brand can be a planned or otherwise complex effort… or a lucky accident too, if one of your titles happens to become very popular and you’re suddenly offered similar ones. In the case where that followup work is also successful, it only encourages them to actively pursue that path further. Post-Yuru Yuri Dogakobo has put together about a dozen colorful, cute titles about schoolgirls fooling around. More recently we have the example of White Fox, who after the mega-hit Re:Zero have started getting bombarded with requests for fantasy titles with a dark spin to them.

If you take all those factors to the extreme, you get a company that’s so far removed from the rest of the industry that it might as well not belong to it: Kyoto Animation. That statement is quite literal when you consider that, unlike every other sizable studio, 99% of their staff only ever work on their own productions – that exception being some Shin-chan work, as a legacy of the studio’s origins. The norm in the anime industry is to pick up assistance work all the time, so that you don’t have staff sitting around during production bottlenecks and to earn some much required extra money. KyoAni stopped doing that ages ago, so their staff – mostly composed of people who joined young without experience elsewhere – is never in direct contact with other companies. It would have been more surprising if they hadn’t developed some kind of in-house style.

And that stands true on a management level as well. The studio’s success allows them to be picky with what they make, and the way the company operates to begin with is incomparable to their peers. Many of their policies are excellent; anime’s current gold standard when it comes to working conditions, with actual salaries and working schedules that ban recurring overtime, thorough training of young creators as their number one goal, usually sensible project planning, extended maternity care, and so on. Other decisions, on the other hand, border on nonsensical – their strict control on public social media accounts is a Neanderthal’s understanding of anti-leak measures. Even the wrong-headed moves make them who they are though, so if you’re willing to pay attention beyond superficial matters, it’s fairly easy to understand what KyoAni’s identity is like. And if you take that time to do that, you’ll notice a very interesting inner schism: Kyoto and Osaka. The fact that the studio has two branches is well-known, but the notoriously different quirks and priorities of their respective staff tend to be overlooked. As a curious consequence of the company’s motto to only work with the people who physically surround you, the studio has gone beyond studio culture – it has different division culture.

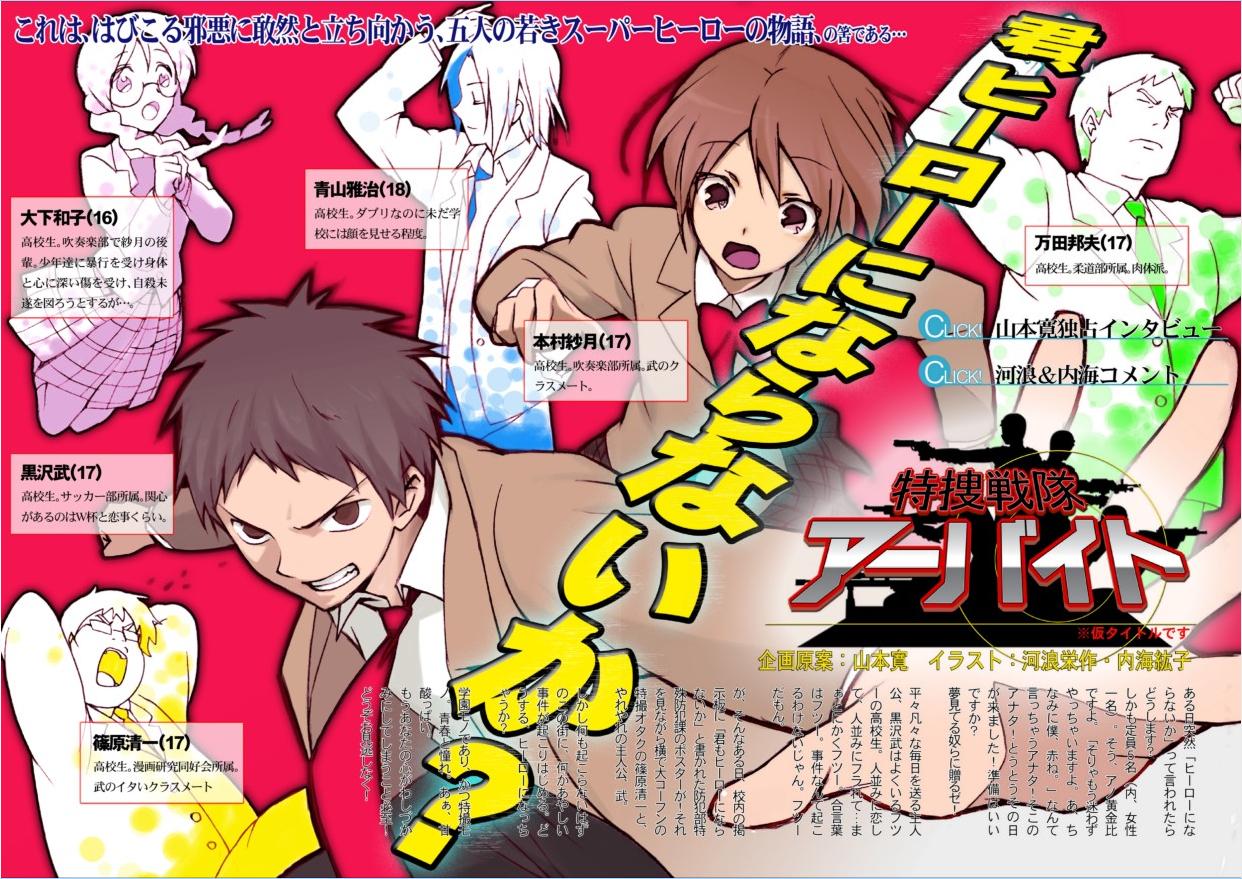

No other franchise exemplifies this better than Free!, hence why the start of its third season offers a perfect chance to talk about this. Truth be told, the series has been unusual ever since its inception. Back in 2011, Koji Oji’s tale High Speed! received an honorable mention in the 2nd Kyoto Animation Awards – the same year Beyond the Boundary was also given that very minor prize. It’s a custom within the company to, with the blessing of the author, put together fairly liberal adaptations of awarded titles that are deemed to have potential in anime form. Those are officially considered original anime by the studio, not only as a way to highlight their ownership of the KA Esuma imprint but also to mark how transformative these adaptations are. But even among those, Free! is an exceptional case. As much as the promotional tools and anime itself want to claim otherwise, Free! is not High Speed!, and High Speed! is not Free!.

That rift was first created when the concept ended up in the hands of none other than Hiroko Utsumi, who had become the highest regarded episode director at Kyoto Animation’s Osaka branch, Animation Do. She usually formed a star team with Miku Kadowaki, which worked out so well it earned them both the possibility to be entrusted with an entire series. Utsumi gave High Speed! a read and sensed something compelling in the characters’ bonds, but wasn’t convinced at all about the middle school trappings. She doubted its appeal and felt that it revolved around dilemmas too mature for a bunch of kids. The solution she arrived to was to age up the whole cast and instead create an anime series that would act as a sequel-but-not-really to High Speed!, which instead got published in book form. She put together a barebones pitch, and after many revisions (plus some concept art and one viral commercial you likely remember), that led to the broadcast of Free! in 2013.

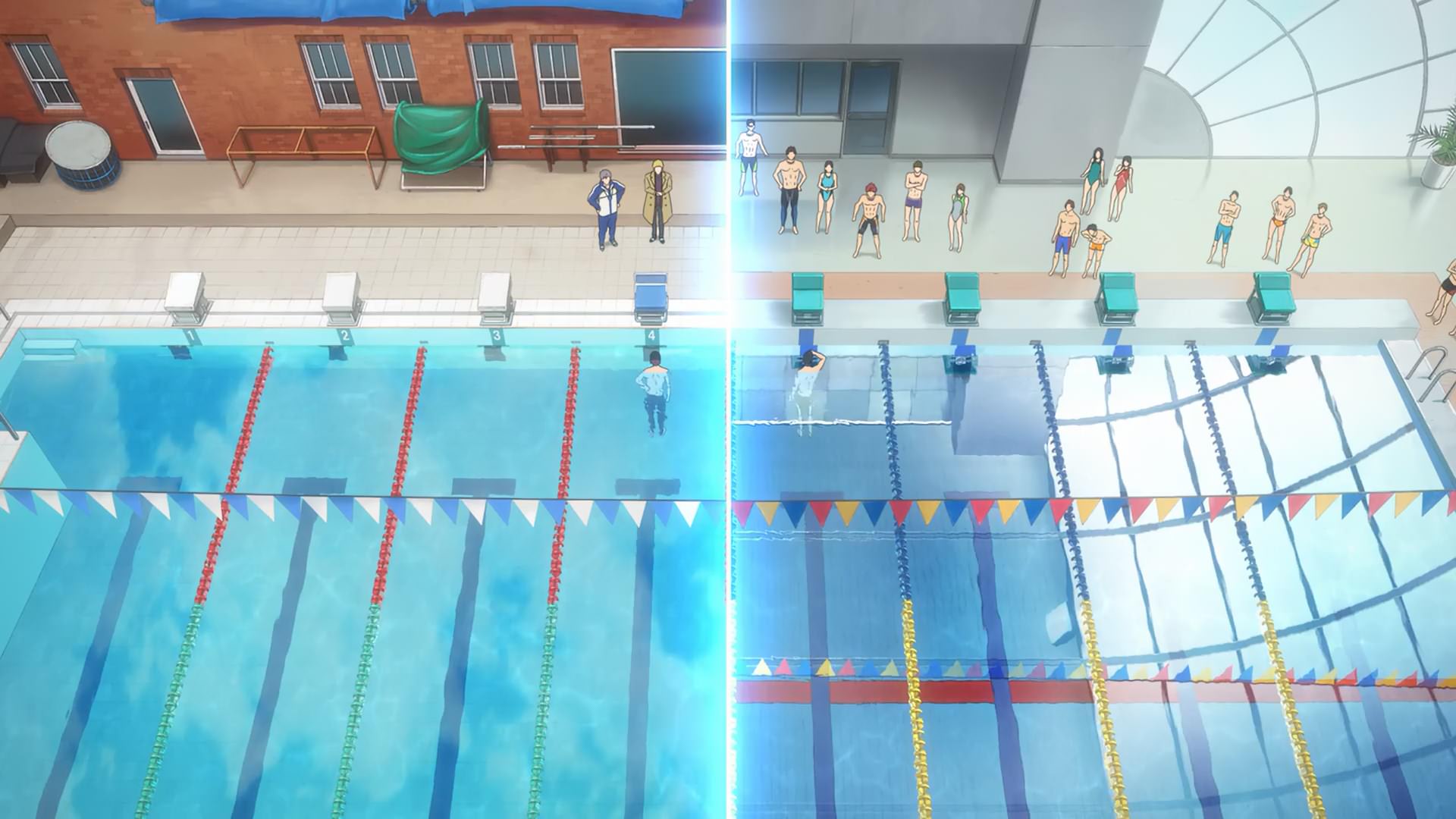

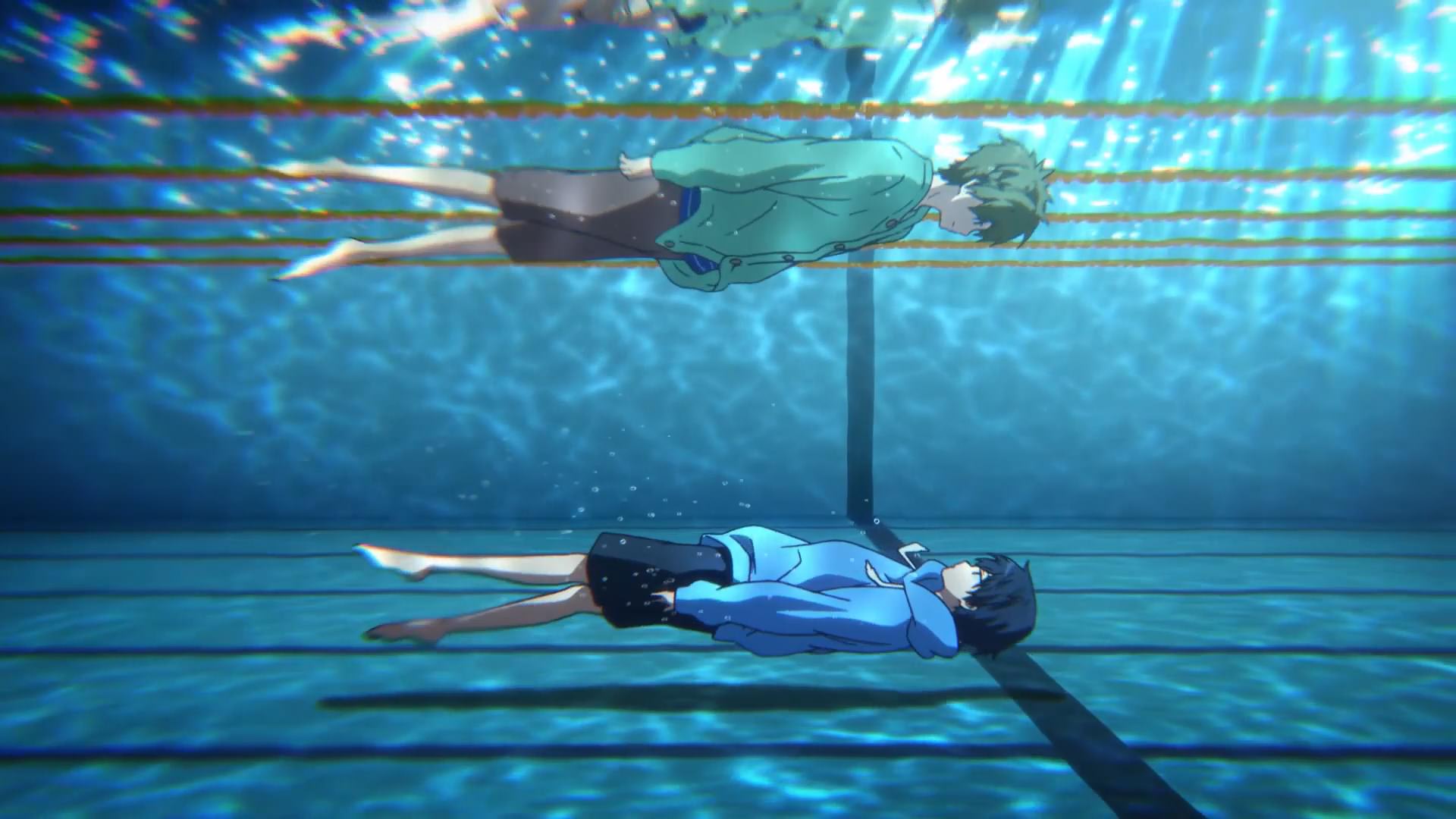

The first TV series, as well as its sequel Eternal Summer, embody Utsumi’s personality and Animation Do’s unique charm. As a storyboarder, she had always stood out as the most audacious voice in the studio as a whole; eye-catching visual concepts, extreme angles, colors that pop, even some Dezaki-esque flair could be found in her work. This was all geared towards making the audience feel something, rather than strictly as a vehicle to convey the characters’ feelings. It’s not that she didn’t consider those, but watching Utsumi’s anime is always observing her personal interpretation of it – there’s no illusion that the cast and narrative are autonomous, everything is obviously distorted by Utsumi’s lens, and that feeling only further increased when she started leading projects of her own.

Free! is by all means a product of that unashamed boldness. The new setting can be pragmatically justified by the fact that Utsumi attended a swimming club while in highschool so those are the experiences she could draw form, but the main reason behind that change was that she wanted to gleefully enjoy the muscles that would have developed at that age. She’s never made an effort to hide that, to the point where Upper Bodies is one of the explicit keywords behind the whole production. Utsumi wants nothing but showcasing what she loves, even if she has to bend reality itself to make that happen; Free! conveniently ignoring the rules and customs of the sport to allow for a certain emotional event is quite the contrast to how all the Kyoto-led projects treat their subject matter, but it’s not surprising in any way when you consider the creative forces behind it. This is what Utsumi and Animation Do are like, and they pack quite the punch.

As it turns out, that particular style does resonate with a lot of people. Utsumi’s work is charismatic like very few other people’s, mostly because of how contagious her enthusiasm is. She has a blast enforcing her personal views and the innate sense to transmit that joy to the viewers, making up for technical shortcomings and sometimes questionable decisions. If you critically analyze the massive off-screen rewriting of Rin’s personality between the first two seasons of Free! you’ll likely reach the conclusion that it borders on nonsense… but do you really care in the first place? His charm in the sequel is immense, and Utsumi’s adoration for the character is palpable, so the show convinces you that it doesn’t really matter. Utsumi’s magnetism draws in countless viewers, both people who are aware of her shortcomings and those who are blinded to them because of the director’s dazzling style. That individualistic wildness runs deep in Animation Do’s bloodline, even if we often only see it as a way to spice up the gentleness of their Kyoto peers. And to this day, Utsumi stands as the greatest embodiment of their identity.

Amusingly enough, the person who best represented her workplace ended that relationship because of the way the company operates; another consequence of having all your staff working full-time exclusively on your titles is that if they ever want to try out something else, they have to leave for good. The allure of freelancing can be strong even if it means leaving behind friends and better working conditions. So by the time a new entry in the franchise was considered, Utsumi was already preparing to amicably part ways with the studio. Losing the central figure in the project up until that point confirmed the need to make something entirely different – hence High Speed! The Movie.

The project wasn’t just a return to the source material (mostly its second book), but also a switch from an Osaka lead to the usual Kyoto headquarters. The director chosen was Yasuhiro Takemoto, who’s always glad to be able to work on projects revolving around the emotional immaturity of boys. As seen in the likes of Hyouka, Takemoto is capable of very gently poking at the insecurities of kids, as if he was personally guiding them in the right direction. His approach is as representative of his branch of the studio as Utsumi’s was, with an equally impressive ability to maintain a recognizable voice throughout very diverse projects; it’s not an easy feat to be able to imbue works as fundamentally different as Maidragon, Amagi, and even Hyouka with similar traits, and yet Takemoto does it as if it were natural.

The resulting movie was understandably quieter, more solemn, but extremely compelling. The road to getting there, however, wasn’t all that smooth. The explicit intention was to create something that fans of Free! would still enjoy, to the point of retconning its original characters somewhere into the beginning of it all. Even though Takemoto is also known for leaving his personal imprint on works he touches, he’s not particularly fond of massive narrative changes beyond structural ones, so it’s not as if this new team was going to reinvent High Speed! to fit within the established anime canon. This friction also manifested on an aesthetic level – the movie was mandated to be immediately recognizable as part of the same series, and yet the design work had to be tweaked to adapt to the different tone. Takemoto and Futoshi Nishiya, a character designer who might as well be a mirror of the directors he works with, discarded the sharpness Utsumi had introduced since the very first piece of art and opted for softer traces and an appearance that subtly highlights the vulnerability of the kids. The success in spite of all the adverse circumstances speaks volumes of the skill of the people involved. High Speed! stands as an easy recommendation for just about everyone, including those who weren’t fond of Free!.

If you thought that was the story of a messy success, the events that followed since then might boggle your mind. Since the popularity of the franchise refused to die down and plenty of staff were still fond of it, the decision to return to the series yet again was made. However, Takemoto’s middle school tale had reached a graceful end, and that meant returning to the present and Animation Do’s jurisdiction. High Speed! hadn’t been as explosively popular as its younger older sibling (it’s a complicated family), but its fans were so dedicated that the staff have been trying to integrate its characters into the story of Free! – a story that had originally ignored their existence and replaced it with conflicts and characters that overlapped their roles. The quest to create a solid continuity – enhanced recap movies and OVAs disguised as a theatrical project, which ignore events that would clash too hard and feature cameos to gradually introduce High Speed!’s cast back into Free! – has led us to odd project that is Dive to the Future. The hot swimming boys have become sort of a Frankenstein’s monster by the time they started reaching college.

What is this third season going to be like, then? A thrilling summer adventure, most likely. Replacing Utsumi, we have Eisaku Kawanami as series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario. for these new iterations. Another passionate member of the Osaka branch, without the sheer charisma of his senior but with a similar overall mentality. Kawanami’s fervor is likely to get directed more towards hot-blooded swimming competitions and as much absurd comedy as he’s capable of fitting into the series without compromising the tone. Free! remains immediately entertaining and has the potential to introduce interesting conflict that expands on the Future theme introduced by the previous season, supported by an interesting set of new characters that aren’t new at all. The franchise is currently a messy mix of virtues from the studio’s two distinct locations, awkwardly glued together and yet somehow still a bunch of fun.

In an industry where studios struggle to establish an in-house style, the extreme case of a company where each building has a well-defined identity is very interesting. It’s affected the studio on every level, to the point of gearing their animation forces in slightly different ways; Animation Do’s sakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. ace is Tatsuya Sato, specialized in ardent emotional outbursts. Meanwhile, newer generations of Kyoto stars are captained by the likes of Nami Iwasaki, who inherited the delicacy and expressive thoroughness that Yoshiji Kigami spread through the studio. Now this doesn’t mean there aren’t exceptions to the rule: Kyoto’s veteran Noriyuki Kitanohara is as impactful as Osaka’s best, while Animation Do’s new director Takuya Yamamura will be imbuing the upcoming Tsurune anime with the tenderness he gained from KyoAni icons like Naoko Yamada. If you look at the bigger picture though, the fact is that each branch of the studio has a culture of its own. The differences between High Speed! and Free! illustrate just how much shared mindsets can influence people’s work, even if they belong to the same studio and are technically working on the same franchise. The curious story of this series is an interesting anecdote that explains its odd growth, but also a fascinating example of the impact studio culture can have in the world of anime.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

the link for “barebones pitch” is broken

Fixed! WordPress mangled that link spectacularly.

Somehow you always come across as disliking Utsumi. Why is that?

I’ve watched everything she’s made, been saying she’s one of the most gifted storyboarders in modern anime for years, and in this post I called her work immensely charismatic and contagiously joyful among other superlatives. If I dislike her, then I’m really bad at it! I’m personally very fond of Utsumi’s work within other people’s frameworks, to the point I considered her among the best episode directors&storyboarders at KyoAniDo of all places – an extremely high bar. But when it comes to series direction, under circumstances where she has no one to tell her to stop, I find her dangerous.… Read more »

Don’t you mean Utsumi is great at episode direction but not so much with series direction?

This was so interesting! I’m really excited to see what kawanami-san does with the season. I’m not a big fan of the episodes he has directed as episode director, but the first episode of Dive to The Future was quite enjoyable.

One question though. Did Yamamura-san move to KyoAni or is Tsurune a Animation Do headed production also? Because Kadowaki-san switches between both studios, right?

I’ve been wondering that since having the series director physically overseeing what other staff and departments do is integral to how they work. For Kadowaki it’d be nothing new though, yeah.

Also, regarding Kawanami – I don’t think he’s anywhere as good as Utsumi, but since he’s respecting her work this much, I think it’ll work out well enough. Both the OP and ED made me laugh because they’re him doing his best to make Utsumi-like sequences (and the ending’s very cute so I think he succeeded with that one).

We will find out soon enough! I’m looking forward to seeing what Yamamura-san does with his first series. I am actually not the biggest fan of either. I didn’t really like ‘Free!’ or ‘Free! ES’ but I watched them anyway because of ‘High Speed! Starting days’ (major Takemoto-san fan here). I was never aware of the episodes that Hiroko Utsumi had directed as E.D., because back then I was one of those kids that thought a studio is a studio and not a collection of individuals haha. What would you consider her most stand-out episode as E.D.? I would love… Read more »

She was already exceptional in Nichijou (quite literally, her team actually made two consecutive episodes!) but I think her genuine masterpiece is Hyouka #21, the Valentine’s episode.

That was her?! That episode was outstanding!

I tried watching the first season last year simply because of how excellent the production looked and the staff behind, but ended up dropping it because the substance and teen angst of it all just bored me death. Having read this and seeing how much the series has changed and rewritten some areas, it gives me hope that maybe I’ll be able to enjoy it more as the series move on. I’ll give another try.

I thought the second season was great already, keeping the fun aspect the series always had and with way more compelling conflict. Even if the road leading to that point was bumpy it was 100% worth it. High Speed! is a plain excellent movie and I feel like DF will be entertaining at worst, so it might be worth revisiting even if you had a poor first impression.

Sorry for commenting on an old article but in case you do see this. I was wondering if you had any idea why High Speed has so many enshutsu and people on sb in a manner more similar to a tv production. Can this be attributed to Takemoto’s approach and maybe not needing it to be his inside-out or just a result of the schedule?

Each act of the movie had different unit directors/storyboarders, the reason being… somewhere in between the middle of those two? Disappearance had 6 directors as well so Takemoto’s workflow seems to lead to that to begin with. Sure he tries to draw a bunch of storyboards on his own shows, but he’s not the kind of creator who has the need to control the immediate execution (like recurring solo movie storyboarders ala Yamada) as long as it follows the themes he’d envisioned. That said, HS deserved better from a planning standpoint for sure. A bit rushed, which I’m sure didn’t… Read more »

Oh I see. I had guessed that he didn’t have the desire to have that level of control based on other comments you had made about him on the blog. I was curious because of Yamada’s aforementioned approach and Ishidate solo storyboarding Mirai-hen. It is cool that Fujita and Yamamura storyboarded as they were somewhat new directors at the time and they’re two of my favorites at the studio. Yamamura especially as it appears that he and Takemoto would continue have an important role in each other’s projects. And yeah, the schedule is unfortunate for the debut ADs and such.… Read more »

Hiroko is horny on main and it’s glorious