A Colorful Leap Into The Next Age Of Anime – 5 Years Of Studio Colorido Works

Over the last 5 years, Studio Colorido has become one of the most beloved studios in the anime industry because of their thrilling, imaginative, and colorful works. What was once a small crew with potential has now become one of the most capable digital teams in animation, leading the pack when it comes to new techniques and embodying the spirit of the new generations of anime creators. And this is how it happened.

Fall 2018 is quite the celebratory occasion for Studio Colorido. Though it’s not their anniversary per se – the company was founded in August 2011 by multifaceted producer Hideo Uda – it marks exactly 5 years since they began putting their delightful works out there. The limited screenings of their first two short films were held on October 13th 2013, while the full version of their first commercial was released on October 18th, so we’ve got plenty of reasons to commemorate the first lustrum of Colorido anime. Half a decade is all it’s taken them to evolve from a promising prospect to being at the forefront of the anime industry in many regards, with a distinct identity and the technical proficiency to live up to the ideas that set them apart. In hindsight, their success might seem like the logical conclusion with the talent they’ve amassed, but observing their evolution makes it clear that we’d have experienced a very different outcome had they wavered on their principles and not made certain choices. To understand what makes them so unique, we’ve got to look back at the short but eventful road that took them where they are now.

In that regard, a crucial step that tends to get overlooked is the very first one. The two major patterns when it comes to establishing new anime studios are teams splitting off existing companies, and entirely new groups of creators coming together under one shared goal. Colorido is often seen as the latter, but that’s not quite correct and sort of misses the company’s actual motto. While founder and current board member Uda had some brief experience in this industry after cooperating with the likes of studio Khara and Gonzo, his background wasn’t in anime, instead leaning more towards management and business matters. As a consequence, the studio he built initially had no creative philosophy whatsoever, no artistic vision motivating its conception. That might be ringing some alarms, but creating that initial blank slate was by all means a deliberate move; though he had no ideas to uphold on a creative level, Uda did have a goal: to establish a studio where artists could work comfortably, shielded from the abysmal working conditions and complicated financial situations that plague anime as a whole. He’d be the pragmatic core of the company, lessening the burden of the creatives and allowing them to become the studio’s leading voices as much as possible. By doing that, the studio would ideally develop a creative ethos along the way. And that it did!

A sample of Colorido’s digital workflow circa 2013, as belatedly shared on their YouTube channel. It has only progressed further since then, becoming integral to their essence.

Who did Uda and his initial team approach in those early stages, then? Since they were looking for artists capable of becoming the soul of their new studio, they chased individuals with a strong personality, taking kind of a scattershot approach. The result was two projects so opposite in nature that they serve as the best example of the studio’s lack of any artistic ideology during its inception. On the one hand there was veteran Takashi Nakamura, a bit of an unsung anime hero. During the 80s he’d played a key role in the growth of Japanese animation, leading the pack with dense work that gained even more texture after he supervised AKIRA. Though he never was as concerned with realism as some of the outstanding artists he inspired, most notably Hiroyuki Okiura and Koji Morimoto, there was an authenticity to his portrayal of people that had rarely been seen in anime before or ever since.

And while as a director he didn’t make quite as much of a splash as he did as an animator, hence his relative obscurity among the fandom, Nakamura’s works are still rightfully held in high regard by those who’ve gotten a chance to experience them (especially A Tree of Palme, an official selection at the Berlinale back in 2002). As a storyteller he proved to have a ludicrous range, seemingly capable of tackling all sorts of genres and tones. But some things remained consistent: the rock-solid fundamentals he gained as an animator, a dignified air that was maintained even during the sillier or most tragic moments… and profound unmarketability, which is why the project he had in mind at the time got scrapped by the studio that was supposed to produce it. Promising him an opportunity to actually bring it to life, Nakamura hopped onto studio Colorido to share their very first adventure.

The result of his effort (and I do mean his for the most part, since he directed, wrote, boarded, and key animated the whole thing) was the silent masterpiece Shashinkan. Multiple generations are framed through the camera lens of a photographer whose only wish is to see people smile. And he succeeds at that in spite of loss being an inescapable part of our lives, as highlighted by catastrophes like the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, the Russo-Japanese war, WWII, and the passage of time itself. The short film captures life, a photographer’s at that, with a rugged style that has no business feeling as immensely delicate as it does. This is a kind yet unflinching work that deserves to be remembered as the start of such a special studio.

Nakamura would return a couple years later for Bubu and Bubulina, Colorido’s contribution to the Animator Expo program – a quirky tale of sisterhood that also happens to deal with the struggle to find an audience, brought to life by similarly rough lineart and acting that once again encapsulates Nakamura’s animation philosophy. Despite that successful relationship, however, the director amicably parted ways with them to continue his career with other companies from the same network. The reason is simple. By that point, Colorido had already chosen its destiny: to become a vehicle for a new generation of creators, basing their entire operations on digital craft. It’s not as if Nakamura was unwilling to embrace tech advancements, as he’s recently been involved in hybrid and CGi productions, but he knew the studio was geared to accommodate youngsters who had grown up with these tools rather than a veteran experimenting with them for the first time in the later stages of his career.

The mastermind behind the studio’s newfound doctrine was the other creator sought by Uda at the beginning of Colorido’s life, none other than Hiroyasu “tete” Ishida. Though he barely had any professional experience (assisting his ex-professor Gisaburo Sugii on The Life of Guskou Budori was all he’d done since graduating), Ishida was already popular enough to be entrusted with a leading role in this new adventure alongside a figure as prominent as Nakamura. In 2009 and while still a student, he’d rocked the entire world with Fumiko’s Confession; this frenetic short film earned the praise of critics and fans alike, winning awards in festivals worldwide and going wildly viral, as you can tell by the fact that the main upload on his channel keeps edging closer to 5 million views. Although his obscenely gorgeous graduation piece Rain Town proved Ishida wasn’t a one-trick pony by offering a solemn and melancholic sensorial experience, which deservedly won a handful of awards as well, it’s the positive exuberance of Fumiko’s Confession that would go on to define Ishida’s career – and as consequence, set Colorido’s path as well.

However, it’s often said that the greatest studios need at least a couple of pillars to sustain themselves. Multiple leading voices to ensure some diversity, even if there’s a clear ethos to the company as a whole. Perhaps this simply comes down to attempting to replicate the unmatched success of the Miyazaki and Takahata partnership, but it’s precisely Ghibli that we’ve got to talk about at this point. Ishida wasn’t about to tackle his first challenge at Colorido alone, and the main ally he contacted was someone who had been working at the legendary studio for a few years. Yojiro Arai actually intended to become a background artist, which will surprise no one who’s experienced the peaceful, bucolic greenery from Colorido’s works; this is an aspect that was always present in Ishida’s early works as well, but ever since his career got intertwined with Arai’s, the aspect that makes all the Ghibli comparisons going around meaningful for once was strengthened.

The first turning point for Arai was watching Eureka Seven, immediately falling in love with Kenichi Yoshida‘s design work. After reading that Yoshida started his career at Ghibli, Arai made that into his new goal. And lo and behold, he did make it into the demanding studio… then reality slapped him in the face, reminding him that the dreamlike job at Ghibli also required nightmarish dedication. While he was in the midst of struggling with that, though, he was contacted through Pixiv of all places by Ishida, with whom he’d been acquainted with for years. The proposal he received, to leave the highest regarded studio in favor of an unproven new adventure, was risky to say the least, but he quickly realized that he made the right choice by saying yes.

That collaboration led to the other inaugural piece for Colorido’s activities: Hinata no Aoshigure, also known as Sonny Boy & Dewdrop Girl. Arai, who had never even officially handled key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. duties, became the character designer and supervised the animation, while Ishida made his professional debut as a director, writer, and quite the long list of roles. The absurdly charming result captures the appeal of the studio to this day, even after all the changes they’ve gone through. Their work still has that appealing aesthetic that mixes Ishida’s initial sensibilities with the Ghibli influence that Arai carried, with sceneries that range from pastoral to surprisingly vivid urban settings. That influence can be felt on some level on a thematic level as well, since this was the first of many Colorido pieces to view the world through the eyes of children, using their imagination as the catalyst for the magic of animation. And since Ishida’s never been shy about his proclivities, his first short film at the studio could only be a sweet, straightforward romance that sets up the perfect scenario for his renowned soaring imagination. If you’re still not acquainted with Colorido’s work, Hinata no Aoshigure remains an excellent showcase of their allure if you want to check whether their work resonates with you or not.

As mentioned earlier, though, Shashinkan and Hinata no Aoshigure aren’t the only two works they managed to squeeze into their busy start of operations back in Fall 2013. Having wrapped those up comfortably early, the studio had time to produce a little work that was nonetheless pivotal for the company. WONDER GARDEN, a commercial for the thematic Control Bear store that was opening at the time, marked many important first times for the team; it was their first animated advertisement, Arai’s own directorial debut, as well as the first full piece the studio shared online. The significance of allowing Arai to take the reins for the first time is self-explanatory, but the other two points are key when it comes to understanding Colorido’s viability as a company. As you might have already heard, advertisements for companies outside the realm of anime are so much better remunerated than standard work that there’s no point in even comparing, making it a very appetizing pathway for smaller creative crews. And, although Arai’s fantasy ideas are ironically less magical than Ishida’s more mundane imagination leaps, he’s still got that special touch that immediately gets your attention, which is very important when it comes to short pieces and commercials in particular.

It’s no surprise then that WONDER GARDEN was the first of many Colorido commercials, with all sorts of companies rushing to request a fancy ad of their own. In FASTENING DAYS (a narrative series of commercials for zippers of all things), Ishida saw a great opportunity to put his masterful traversing of three-dimensional environments to good use, whereas Arai exhibited the influence his colleague had on him with the beautiful pastel color ads for Puzzle & Dragons. But it’s not just the two studio leaders who got to make them; though on a certain level being contracted by a company to advertise their services is quite restrictive, the shorter format and vague requests they received also allowed lots of experimentation, even by outsider directors and other acquaintances of the staff members. Youngsters like part of the team behind the viral McDonalds ads got entrusted with a project for the first time, while other short productions got to differ from the norm in curious ways.

Look no further to the latest Colorido commercial Susume,Karolina – a promotional piece for Karolina Styczyńska, the first non-Japanese professional shogi player, directed by fellow Polish Mateusz Urbanowicz and sponsored by Calorie Mate. Which is to say, a nutritional food complements company paid for an ad that served as the directorial debut of a renowned background artist, dealing with quite an unusual topic in the first place. See, there’s plenty of space for inventiveness in the advertisement space after all.

The Puzzle & Dragons commercials directed by Arai show the strong influence Ishida had on him – that cartoony, fantastic leaping could have easily come from the latter’s mind.

Both Ishida and Uda have recently admitted that they plan to keep on producing commercials, meaning that on a creative and financial level, Colorido is completely in agreement that those will remain an important venue for them. But it’s not the time to wonder about the future quite yet, since the next important step in grasping the studio’s identity involves the second animated advertisement they created, the next major work following that busy Fall of 2013. To celebrate the 10th anniversary of Fuji TV’s noitaminA timeslot, the studio was contracted to produce a 3 minute long short film that would be screened during the commemoration and then uploaded online, as well as a splash screen that was used during TV broadcasts throughout the year. Paulette’s Chair is a whimsical yet straightforward piece that once again flaunted Ishida’s biases. Unashamedly so, again. His ability to create iconic imagery in a way that comes across as effortless and genuine proved to be perfect to celebrate a whole decade of one of anime’s best-known timeslots.

It wasn’t the charm of their work that made it such a noteworthy event, though, but rather the establishment of a key relationship. Avid readers of this site might remember the name Koji Yamamoto, who at the time acted as noitaminA’s chief editor. But even if you didn’t know him, his goal will immediately sound familiar: to build a space where artists can do their thing without worrying too much about the financial and management matters that often neuter creativity in anime. To shield them from this industry’s problems, pretty much word for word as Colorido’s founder Uda said he wanted to. While noitaminA’s initial motto to offer quality programming for underserved audiences had done some good, that effect was gradually being diluted, so Yamamoto began coming up with new initiatives. And those eventually led to the foundation of the Twin Engine network, which Colorido is now a core member of. Those shared values and crossing paths at exactly the right moment led to a relationship so strong that Yamamoto has actually been acting as Colorido’s representative director since late 2016, when that partnership was solidified.

The consequences of that bond led to the next major development for the studio – both in its relevance and sheer scale, since it was the biggest project they’d undertaken up until that point. Colorido and Fuji TV partnered up with TOHO to bring the 26 minute short film Typhoon Noruda to theaters on June 5, 2015. Perhaps this sounds like a small step up, but keep in mind that they were still a tiny studio with barely any professional work at the time, so this was quite the high-profile homework they were assigned. The short film switched the script from most major Colorido works; this time around it was Ishida who provided the character designs, a bit more mature and refined than usual, while Arai was in charge of all directorial duties. Since by that time the studio had already managed to catch the eye of quite a few people in the industry, the project also served as an opportunity to attract various outstanding guest animators. Between that and their usual captivating art direction, it’s no surprise that Typhoon Noruda is downright gorgeous.

Unfortunately, the film is also rough around the edges in a way that Colorido’s simpler works had never been. Even if I don’t tell you that Arai had based it all in an illustration he’d drawn as a child, you could have guessed that its origins were something along those lines simply based in the juvenile storytelling and the awkward clash between the relationships it wants to develop and the confused sci-fi narrative. Colorido’s works until that point had been essentially perfect realizations of their ideas, but Typhoon Noruda showed that if the studio wanted to create something more complex, they were better off finding writers who could channel their vibrant energy. But rather than being discouraged due to the messier package, I found the movie to be exciting proof of the room for growth Colorido still had, and how much better things could be if they found the right allies.

Following Noruda, Colorido proceeded with their steady growth while producing a handful of those aforementioned commercials, keeping a lower profile while preparing their next big development. Along the way they hired new staff, reaching the few dozen they’ve got nowadays. A substantial increase, and yet not too many, as they’re aware that a modest size is required to maintain their healthy environment as is. That expansion also enabled them to experiment with other formats, like handling the production of a fully outsourced episode of TV anime in the form of Battery #4. But since Colorido feels more comfortable when crafting their own energetic works than they do helping out other teams (as it tends to happen with studios that develop a distinct personality), tasks like that were quickly put on the back burner in favor of something bigger: their first feature-length movie.

First announced in March 1st 2018, Penguin Highway promised to be a thrilling summer adventure. For the first time, the world would be seeing Hiroyasu Ishida’s work on the big screen for an extended runtime. And adapting the delightfully quirky work of Tomihiko Morimi, no less! Prior to the premiere, Ishida admitted that heading such a large project for the first time was already enough of a headache, so he abandoned the idea of creating something original and instead chose a source material to adapt very carefully. The whimsical nature of Morimi’s coming of age story, equal parts straightforward romance and morphing penguins, turned out to be as compatible with Ishida’s own qualities as he’d imagined, even actively encouraging his own quirks. As the director he was able to provide a thoroughly joyful experience, but also to isolate themes like the pathways and make them into a motif, the visual core of a deceivingly smart film. Penguin Highway is a cute movie you’re bound to have fun with on your first watch, and the kind of work that will refuse to leave your mind afterward, no matter its rougher spots. Feeling like more than the sum of its parts is definitely part of the Colorido brand!

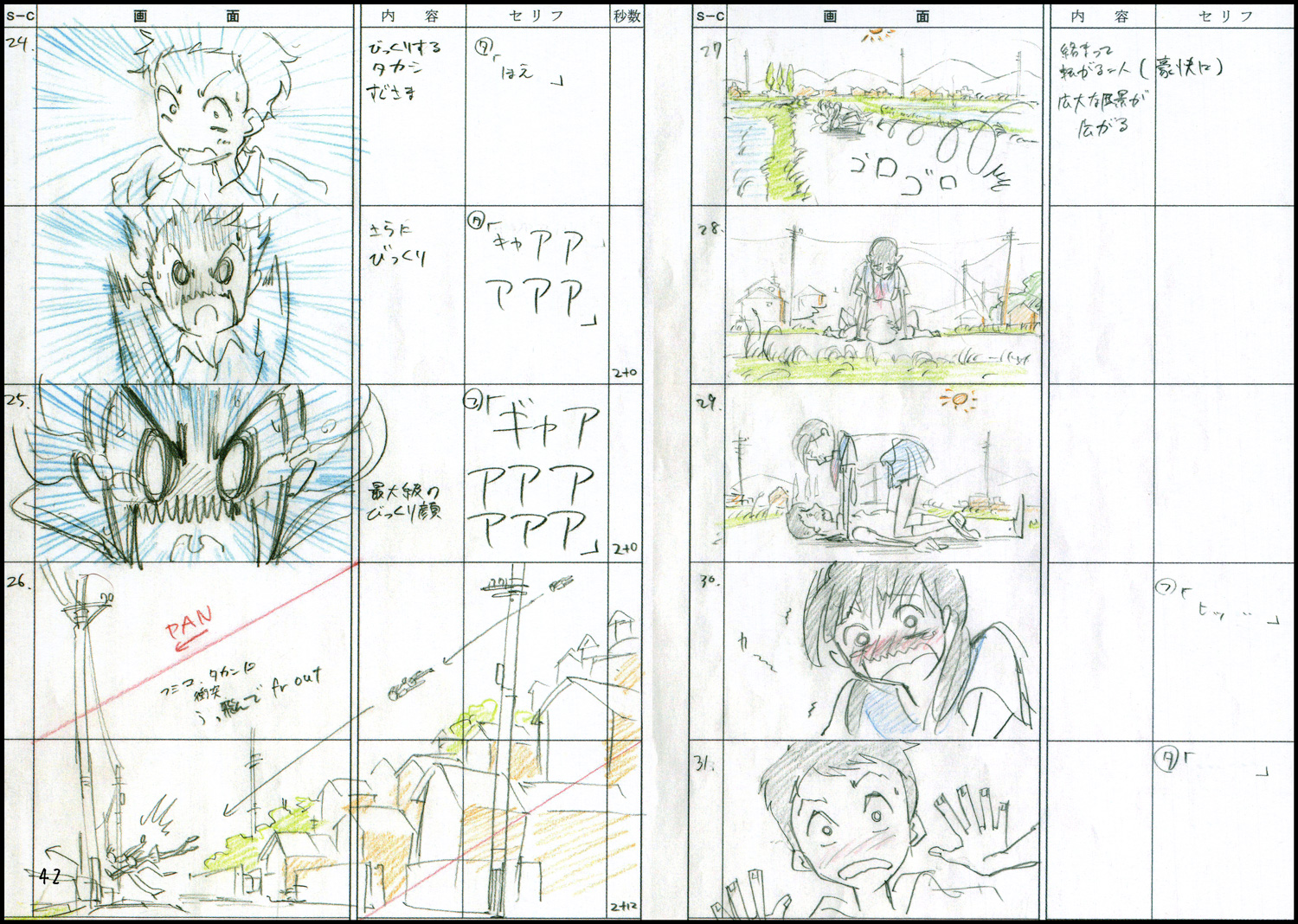

There’s no denying, however, that there were some growing pains in moving from shorter works to a feature-length movie. Some of Ishida’s previous uncluttered elegance was lost along the way, and while the movie will give you more to chew on than his previous titles, it’s perhaps not as thrilling on a base, almost instinctual level. The production fared brilliantly in their scope increase, but they’ve also admitted that it didn’t represent as much of an advancement for their workflow as they’d have liked. Each of Colorido’s projects is seen as an opportunity to expand their digital pipeline after all. Until Paulette’s Chair all the early stages were still analog, but from FASTENING DAYS onwards the layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists. became digital. Typhoon Noruda marked the switch to drawing the storyboards on a tablet using CLIP STUDIO, and they followed up on that by beginning to draw the concept art digitally as well.

Penguin Highway represented some notable advancements too: everything from the early sketches to the finished product was crafted digitally, settling on StoryboardStoryboard (絵コンテ, ekonte): The blueprints of animation. A series of usually simple drawings serving as anime's visual script, drawn on special sheets with fields for the animation cut number, notes for the staff and the matching lines of dialogue. Pro and TVPaint for the animation as their new tools of choice. Everything in their hands that is, since they had to rely on generous amounts of outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio. to get the movie finished – most notably for an entire chunk of the film fully subcontracted to studio WIT, who produced it through more traditional means. Colorido’s current goal is to be able to maintain a fully digital pipeline by 2020, but this served as a reminder that unless they grow to the point they can actually sustain a full production, they won’t be able to make their dreams a reality. Consider this exhibit one million that self-sustainability is a requirement for any anime studio with ambitious goals regarding the way they create anime, no matter how interesting the results of collaborating with other companies may be.

It’s worth noting that those dreams weren’t born from an allergy to traditional artistry, which many of their members actually try to echo in the studio’s productions. The root is clear: Colorido identified the awkward cohabitation between analog and digital means of production as the cause of major inefficiencies in the anime industry. Forced to pick a side, they stuck to their guns and followed the path that had been illuminated since Ishida became their de facto creative leader, meaning digital supremacy. Other key members like Arai have expressed that the efficiency they seek with a cohesive workflow isn’t just meant to make management matters easier, but that it also does wonders for artists doing hands-on work like him; after his traditional training at Ghibli, Arai fell in love with digital tools that eased his troubles and let him concentrate in breathing life into the characters. There’s no denying that Colorido has managed to gather quite the skillful crew of youngsters, but the role that their environment and production methods play in the liveliness of their work can’t be understated.

Although they haven’t quite reached their ultimate goal, then, Colorido’s gotten close enough that you might think there are no surprises awaiting. Even as they’ve grown and their responsibilities have increased tenfold, they’ve maintained that cheerful workplace that allows creators to focus on what they love. The studio developed a distinct personality rooted in the worldview of their members and the tools they use, and the company’s devoted itself to those with no hesitation. And yet Colorido’s still found another way to make themselves into a more exciting prospect, not just in future possibilities but on an immediate level. And amusingly enough, it’s an old acquaintance rather than a newcomer that heralds this new development.

A sample of Penguin Highway’s very Ishida-esque stampede, boarded and key animated by Tatsuro Kawano.

Hiroyasu Ishida’s career has been tied to that of Tatsuro Kawano since before either of them even had a career to speak of. Kawano was Ishida’s junior back in their days at Kyoto Seika University, and to say that they enjoyed working together would be an understatement. The first major result of their collaborations was Fumiko’s Confession itself, which despite being Ishida’s baby, had Kawano in quite the important role as its co-animator; as they fondly recall, it’s hard to attribute individual cuts to either of them, since they drew, in-betweened, and painted the whole thing together as colleagues, without concerns about how things are done in professional spaces. They eventually parted ways, with Ishida’s career following the path we’ve covered and Kawano becoming a digital animation ringleader of his own: praised for his animation skill, quickly establishing himself as a worthy heir of the Shingo Yamashita school of direction, and also standing out for his exceptional networking abilities.

If you’re acquainted with how anime operates, you might not be surprised to hear that it’s often that last point that manages to make the biggest difference. Kawano’s talent and charming personality have allowed him to surround himself with other outstanding artists who are always up for working together again after crossing paths with him; this includes exceptional Pierrot-affiliated animators from his early days in the industry, Tatsunoko’s renowned webgenWebgen (web系): Popular term to refer to the mostly young digital animators that have been joining the professional anime industry as of late; their most notable artists started off gaining attention through gifs and fanmade animations online, hence web generation. It encompasses various waves of artists at this point so it's hardly one generation anymore, but the term has stuck. troops, studio WIT stars he met as Kabaneri‘s action leader, plus all sorts of promising individuals who have attended the Animator’s Dormitory like he did. They all gather around him on his works and the self-published books that he enjoys putting out at events, especially those who are young and intrepid like he is. It’s no exaggeration to call him one of the leaders of the new generations taking anime by storm, so his newfound position leading an entire team within Colorido is quite the big deal.

Natsuki Yamada is poised to become one of the most important new animation figures at Colorido through Team Yamahitsuji.

The truth is that even as a freelancer, Kawano had made a point to assist his friend’s studio when possible, but those collaborations have escalated as he joined the company for good and founded a crew provisionally named Team Kawano. It included exceptionally talented acquaintances of his with very diverse skillsets, from the soft animation of Natsuki Yamada to the sensual appeal of ex-SHAFT Taiki Konno, already singled out as one of the most promising up-and-coming figures in anime. The potential of this new sub-unit could be felt for the first time on the fourth Boruto opening – a downright gorgeous relay of warm and thrilling animation, led by Kawano himself and with the inestimable cooperation of Shingo Yamashita on photographyPhotography (撮影, Satsuei): The marriage of elements produced by different departments into a finished picture, involving filtering to make it more harmonious. A name inherited from the past, when cameras were actually used during this process. duties to present everyone else’s work as clearly as possible. This crew (officially rebranded as Team Yamahitsuji as of the production of that opening) has a different flair than the rest of Colorido, but ultimately their ethos fits the company like a glove: a group of youngsters creating vibrant work that could only be achieved via digital tools.

And that’s where we find ourselves, 5 years after Studio Colorido began putting out their animated works. Their wager to build the studio around the preferences of newcomers like Ishida and Arai rather than betting on veterans like Nakamura paid off, and now they’re at the forefront of digital anime production. They’ve managed to grow while maintaining a sustainable, healthy environment that’s so unlike this industry as a whole. Moving forward they plan to keep on making large projects like Penguin Highway but also to maintain their tradition when it comes to shorter pieces, which give both their main talents and newbies a chance to experiment without quite as much risk. And recently, they’ve expanded with an exciting new team that shares a similar mentality in broad terms, but offers stylistic variety and the possibility to collaborate with other fascinating artists.

Anytime it feels like Colorido’s finally about to fulfill their potential and peak there, they leap further while maintaining the same trajectory they’ve had for years. It seems as if only the sky’s the limit for this team – and considering their propensity to launch characters into the stratosphere, maybe not even that.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

i wonder which course did ishida take in Kyoto Seika University?

i looked on their website and theres two different animation courses?

The animation course from the faculty of manga I believe!

Thanks for the great look back at Colorido’s short history! This puts into perspective the effort they took to use the Unity game engine to create the backgrounds for the storyboard and layouts, as well as reusing some of the data for the actual background designs. Since Unity isn’t really well suited for this, they had to program their own workflow in the Unity editor. Unity is really pushing being used for non-interactive storytelling (Unity has produced a few animation shorts themselves and there are more and more being created by others), so I’m curious to see how, or if… Read more »

Two names are seem to be misspelt: “Miyazaki and Takahashi partnership” — “Takahata”, surely; “Tomohiko Morimi” — “Tomihiko”.

Two bad brainfarts, thanks!