Reiko Okuyama And Anime’s Neverending Fight Against Discrimination

Reiko Okuyama’s a legend in the anime industry for her artistic achievements and as an icon at the forefront of the fight for women’s rights in this industry. Now that her name’s entering the public discourse again, though, we have to address an uncomfortable topic: gender discrimination within the anime industry is far from over.

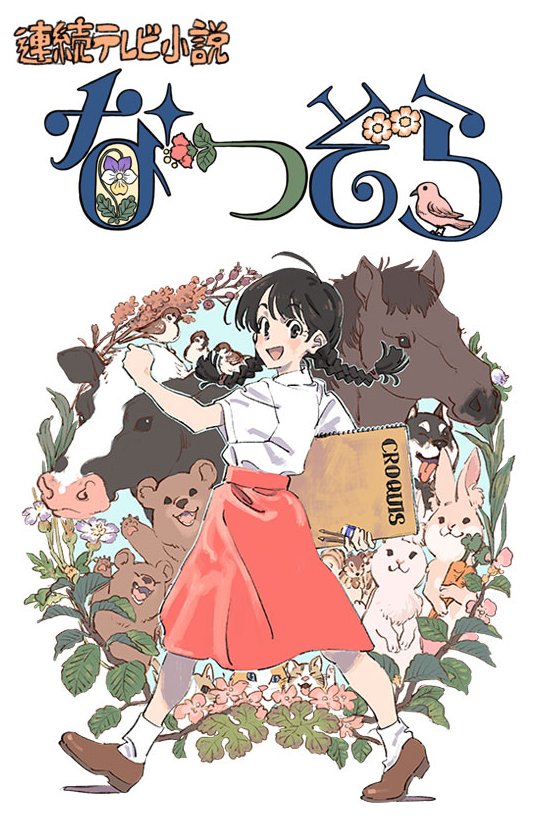

News about Natsuzora, the 100th series in NHK’s popular TV drama slot Asadora, have been circulating for over a year. When it was revealed that it’d revolve around a female animator during the early days of the anime industry, fans were quick to speculate about which real-life figure that tale would be modeled after; though Asadora series are fictional, they’re known to mirror people’s lives every now and then, and this seemed too specific of a scenario not to draw inspiration from a real industry figure. Would it be Kazuko Nakamura, the first woman to act as lead animation director in anime? Or would it instead be Reiko Okuyama, who stands on equal footing as the first woman to supervise the animation in a feature-length movie all by herself despite adverse circumstances (The Little Mermaid, 1975)?

In the end, it seems like the answer was the latter. Late Okuyama’s husband and similarly iconic artist Yoichi Kotabe is being consulted and acting as a supervisor of sorts for the series, which essentially confirms the rumors that were already floating around. Though Natsuzora should be no means be treated as a biography, the intent is to create something that lives up to Okuyama’s legend, and so far they seem to be taking the right steps to achieve that goal. But what was Okuyama like in the first place, and what did she fight for? Let’s find out.

Reiko Okuyama animation reel compiled by Josh H.

Reiko Okuyama joined Toei Douga in 1957 entirely by accident, after misinterpreting the company’s name and assuming they’d specialize in illustrations for children but powering through the trial anyway – and that’s the kind of attitude that’d define her career as a whole. As an artist, versatility was her number one trait. She’d adapt to the geometrical shapes and snappy, caricaturesque animation of The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon just as well as the fluidity and roundness on display in Puss in Boots, a movie that embodied Toei Douga at its most energetic. After an already successful run in the commercial animation scene (first at Toei and later as a freelancer) she branched out even further; illustration work for children as she’d always intended to do, mentorship at the Tokyo Designer Gakuin, even a passion for copper etching works that flourished in the latter stages of her career.

And just as important as her artistic achievements is how hard she had to fight to realize them. As you might imagine, the anime industry in the 50s and 60s was hardly a welcoming place for women with aspirations higher than assisting men with tasks seen as lesser like painting. Her mere presence climbing the production ranks against all odds was subversive, but she wasn’t content with that alone. It’s been documented that Okuyama took a very active role in the labor disputes at Toei, putting her outspoken attitude and natural charisma to good use during the studio’s union conflicts. Risking not only her own career but also her husband’s, suffering multiple setbacks but persevering, she was one of the driving forces in a collective fight that this industry has unfortunately never been able to replicate ever since. Okuyama faced the corporative pushback that also punished her comrades with an extra layer of sexism, a situation that only got more extreme after she gave birth and made it a point to fight for the right of women not to renounce to neither work nor family matters. Her legacy in this regard should be held just as highly as her oeuvre.

This overview of her career, albeit quick, should give you a good idea as to why Okuyama’s life would become the basis for a new entry in a wildly popular drama series. Not only do her achievements warrant that treatment if you observe them objectively, but her whole story’s also got that inspirational vibe that we all love in fiction. Even though the real-life details will be blurred away in this dramatized version, the core of her tale is that of a fight against an oppressive system which can only be won through perseverance – a classic, very relatable scenario. Easy to root for and a good fit for Asadora’s tradition of brave heroines.

The problem comes when you realize that we’re always faster to condemn issues in fiction than we are to effectively address them in real life. Okuyama joined Toei Douga over 60 years ago, and yet that very same studio is still capable of deliberately ruining women’s careers – and they’re not alone in that shameful position. As recently as October 2018, a creator working with Toei (who chose to stay relatively anonymous but whose identity and reports have been verified) opened up about the various forms of harassment that pushed her to sever ties with the studio. After being told that as a woman she didn’t have the right mindset to be a director, justifying lesser remuneration because of her gender, and being disrespected in many other ways, she ended up depressed and with little hope left in anime. An extreme example for sure, but eye-opening nonetheless about attitudes that simply refuse to disappear.

That’s not to say that advances haven’t been made – Okuyama’s own achievements paved the way for that – or that things are just as bad as they were back then. You’ll even find voices in the know that’d argue that gender discrimination within the industry is essentially over. Terumi Nishii, who’s otherwise very critical of anime’s inner workings, has mentioned that she considers such discrimination to be vile but that she feels it has no place in anime’s complete meritocracy; quite the backhanded praise, since she thinks that’s simply a consequence of the industry being in such a messy state that no one’s got the energy to spare to be sexist in production environments.

Looking at her case, it’s easy to see how Nishii’s experience as a popular freelance designer and supervisor who’s actively sought after shielded her from that kind of attitude, but as others have attested, not everyone’s that lucky. It’s important to keep in mind that right about all anime workers suffer from more visible problems: unlivable low wages across the board regardless of gender, impossible deadlines, job insecurity due to the widespread freelancing system, and so on. Greedy corporations (and sometimes middle management) are a clear foe, so the conversation about improving working conditions in anime tends to revolve around addressing that.

On the other hand, sexism is inherently less visible. For starters, it’s a very uncomfortable topic to bring up by the people affected, and privileged groups attempting to maintain the unfair status quo is a harder concept to grasp too. It’s also worth noting that freelance workers can stand on relatively even ground regardless of their gender, as these problems are much more apparent within corporate environments. It’s when female creators are attached to a studio for long periods of time that they start facing a myriad of issues that hold back their career – dismissive attitudes, lack of chances for permanent promotions, lower salaries, no real support when it comes to matters like maternity leave… If we return to Toei, perhaps the biggest worry aren’t the admittedly unusual extreme examples of bigotry like the one we brought up, but rather the fact that there all 17 high ranking executives at the company are men. And while they may not be prejudiced themselves, it’s incredibly lopsided frameworks like that where sexist sleazeballs like the production manager who drove off one of the studio’s most brilliant prospects feel enabled in their beliefs.

As we mentioned, the problems that this creates manifest themselves in multiple ways, most notoriously in the form of glass ceilings. I believe that it’s a big mistake to frame this issue simply as “women struggle to get promoted to directorial positions,” though; not only does that ignore the many other paths in this industry where women have a harder time moving up, it also implies that directors stand on top of everyone else even though that doesn’t correspond to actual studio dynamics. Nishii also had a solid point when she said that anime’s other problems make the industry accidentally immune to certain kinds of discrimination, but that only seems to be in full effect with strictly animation-related duties as those are the positions that all teams are most desperate about. But when it comes to other key positions – producers, decisive management roles, supervisors, directors, you name it – then there’s an oh-so-mysterious sluggish rate of female promotions.

Now if you want some encouraging news, it’s worth noting that like in many other scenarios, discrimination in anime is fated to lose. For quite a few years at this point, most newcomers in the industry have been women, so even sheer inertia slowly moves us forward. While productions where all key positions are occupied by women were very rare a decade ago, they’ve been slowly becoming less exceptional – not that those are inherently superior nor a magical solution to this problem, but their increase is symptomatic of larger changes. It’s a tragedy that disgusting attitudes within Toei drove off a brilliant artist, but women like Haruka Kamatani and Megumi Ishitani have become new ace directors at the studio held in the highest regard by everyone in the production crews, so even a biased system won’t be enough to put a stop to their exceptional careers. If we look elsewhere, companies like Kyoto Animation (who recently improved their maternity leave system with a bulletin sent to employees on a break so that they don’t feel alienated from the productions) show the way forward.

And yet here we are, still having to report depressing cases and a disappointingly slow general progress. Things have indeed improved and are bound to get better, but we can’t get complacent, because the moment we look away these attitudes manage to perpetuate themselves for a few more years. So with the upcoming broadcast of a TV show inspired by an individual at the forefront of the fight for women’s rights in the anime industry, let’s issue another reminder that this battle is still being fought, even if it’s gotten quieter in recent times.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

Thank you for writing this article. I always appreciate your insight about the industry, but this topic in particular is always an extremely divisive one and I’m glad you’re willing to write about it. I’ll definitely try to watch Natsuzora if I get the chance.

I sort of owed the post to a friend who was really hurt when she found out about that specific instance at Toei, so I’m glad I managed to find a way to tackle the issue that wasn’t just reporting on such a depressing incident (which is something that WAS important but would have made for a very downer post by itself…)

Thank you so much for writing about this! Not only are these great for getting insight into an industry where I’d normally have trouble due to a language barrier, it’s just very important for people to know what labor looks like and to be aware of the problems that plague it. Across the seas, here in North America’s animation industry, we’re currently facing similar problems, though thankfully nowhere near as drastic as anime’s problems sound. It might be kind of presumptuous of me to say this, but I feel almost a sense of unity reading this article. Between the terrible… Read more »

The core problems are honestly the same, but it still feels important to be able to detail the specific forms in which they manifest in each industry – especially since the people with power and no interest in change feed on misinformation and vagueness. The people calling the shots in anime are depressingly good at that, hence why positive change is so slow.

It’s particularly important because as far as some fans of the industry will say, Japan has “no feminism.” An insane misconception used to justify sexist attitudes both in Japan and in North America…

The question is what is meant by feminism. I have already seen attempts to declare every second fanservice CGDCT “feminist” only because there is “about girls without boys”. In the western anime fandom, such words have long been turned into clichés that people use to protect favorite titles.

It is symbolic that I got three minuses, but not a single answer. At the same time, the fact remains. For example, I still hear that “K-ON is a fully feminist anime because it was created by women for women”, “accidentally” not mentioning that the author are male and that it was published in a seinen magazine. Feminism does exist in Japan, but you should not immediately attribute to it the western political views.

Dedicated artists profiles without none of this stuff that mysteriously bothers you so much: https://blog.sakugabooru.com/2017/11/30/animes-future-yoko-kuno/ https://blog.sakugabooru.com/2017/11/10/animes-future-mai-toda/ https://blog.sakugabooru.com/2017/09/29/animes-future-haruka-fujita-and-akiko-takase/ https://blog.sakugabooru.com/2017/08/18/animes-future-china-and-megumi-ishitani/ Female creators get otherwise talked about in pretty much every post where we try to interpret the artists’ goals or explain what happened behind the scenes. You’re under no obligation to read the posts on this site, but it’s hard to take ridiculous claims like that as genuine when all you’re doing is popping up in the comments for these out of the ordinary articles in particular to argue with multiple people (by yourself really, since no one was really engaging yet… Read more »

I am not accusing you of anything, if only because this is your personal site and I have no right to demand anything from you. If I didn’t like the content of your site, I just wouldn’t read it.

I couldn’t really tell from the article, but is “Natsuzora” and “Asadora” like a live-action docu-drama or is it something animated?

Asadora is NHK’s morning live-action drama slot/program, and Natsuzora is the title of this particular upcoming series. Not an animated thing, though it’d be neat if this one had a short animated opening of sorts considering the content.

While reading this, you got me thinking about many of the problems also plaguing the video game industry in Japan. I’d say they’re pretty similar, but I think one of the larger reasons for the JRPG decline has more to do with conservatism on the older generations’ part and, for the most part, not letting fresh blood take the reigns. On a side note, I still wonder about what exactly happened that ended Soraya Saga’s involvement in the Xenosaga franchise and an early axe to the series.

It is more interesting to me why we cannot talk about female animators without any emphasis on the fact that they are “female”. Does this have to imply that being female makes an animator better, or worse than men, who should be referred to as “ordinary” animators? Sexism is a separate issue and it does exist in any human society, but I’m a little worried that female directors or animators are rarely mentioned outside the context of politics and their gender.

Huh? Don’t you read the other articles of this blog? Woman are quite frequently mentioned, without any emphasize on gender and politics. Gender equality is an issue which is why articles like this one exist in the first place, but it’s not like this is the only context female animators, production managers or directors are ever mentioned in. You don’t even have to look far for that – the widespread praise Naoko Yamada received for Liz and the Blue Bird, is one of the major recent examples.

I remember very well the material about Yamada herself, in which there was also a section on gender equality and where the author even had to “justify himself” by mentioning that Yamada herself didn’t raise this gender topic. And do not distort my words, in my post was not “the only context” I only said that I rarely meet articles about important women in the industry without a single mention of “progressive” issues.

Thank you for this article. I’m looking forward how the anime landscape will look in one or two decades.

One recent negative example that was kind of eye-opening to me was the production of the new Ekoda-chan anime. It is a manga written by a woman for women, yet all 12 directors are men. Some of them openly admitted in interviews that they don’t really get Ekoda-chan. Not saying their interpretations of the manga aren’t creative or worthwhile or anything, but it’s quite indicative of the mindset of the people in charge.

The Ekoda-chan case gets even worse when you realize they opened up with an episode directed by Daichi Akitaro, who’s been outed as a sexual harasser – it’d happened before already but the accusations went into much more detail just a couple of weeks ago. A shame that a project that’s fascinating in many ways was tainted by terrible decisions on a production level and the involvement of pieces of garbage like him.

I understand what you mean by mentioning this example, but in a different light it looks like an strange hint that women should make content for women, and men for men. Not to mention the fact that “for women” sounds a bit strange in the context of manga, which is published in the seinen magazine with Aa! Megami-sama! and Vinland Saga. Ok, let’s take another example. Many people complain about Domestic na Kanojo, blaming the female author for writing the male MC as a boy with a completely “female soul and behavior”. Personally, I find it rather rude, especially in… Read more »