Pokemon Sun & Moon Production Retrospect: Animation As Character And Tone

Pokemon Sun & Moon‘s TV series wrapped up after 3 years, and Pokemon is now embarking on a whole new adventure. Let’s explore what made its production a resounding success: not the individual accomplishments like pipeline improvements and animation-friendly designs, but rather how all those aspects came together cohesively to define the show’s identity.

Despite the extraordinary endurance of its popularity, Pokemon is the very definition of an iterative franchise. I don’t think it’s fair to say that the actual teams behind the property are just comfortably riding that inertia, though; if anything, I pity the creative leads stuck in a position where older fans demand change in a pattern that’s remained fundamentally the same for decades, while at the same time an equally sizable chunk of that fanbase – sometimes even overlapping with the previous group – reacts poorly to any addition or modification to the formula, minor as they may be.

Mind you, this is a simple observation rather than an attempt to pass judgment on anyone’s feelings on Pokemon’s perceived stagnancy. I personally find the general structure of the games to have a timeless appeal, and value each new release as a familiar, warm place to return to. That doesn’t mean I don’t see where the people who ask for Pokemon to reinvent itself are coming from, even if their reasonable petitions can get drowned by a loud subsect of actors who have specialized in screaming about a massive property aimed primarily at children not catering exclusively to them.

As much as I prefer to focus on positive aspects to celebrate, it’s impossible to discuss what the Sun & Moon anime has been without acknowledging the broader context of the franchise, and that includes keeping in mind the bitter responses too. Much like the games, the TV series tends to use its soft reboots to tweak the formula somewhat. Ideally, the goal is to marry the technological advances that studio OLM strives for with the specific goals that the creative team has for that particular season. In practice, things don’t always work out that smoothly. But three years after Ash’s arrival to Alola, I can confidently say that the staff’s vision when it comes to tone and structure, the updates on their toolset, and Pokemon’s own identity had never been in such perfect harmony before.

Now that Sun & Moon has come to an end and we’re starting a new era of Pokemon anime, it’s the perfect time to look back on the production over these last three years and to find out what made all pieces click together in such an organic way. In retrospect, Sun & Moon might very well be the most fully realized iteration of Pokemon, and that’s something you might be able to appreciate even if the style they were going for isn’t up your alley.

Again, it would be a mistake to judge Sun & Moon in a vacuum. Although Pokemon pundits circa 2016 loved to tell everyone otherwise, it’s not as if OLM’s crew had woken up one day having decided to ruin your childhood by making Ash look like a goofball. At the same time, the studio didn’t come up with a digital production panacea overnight either, which is the more production-savvy but still overly simplistic answer that gained traction to explain the seemingly sudden aesthetic overhaul. It’s important to understand that, while Sun & Moon marked a clearer departure from previous series than ever before, many of these changes were simply the natural next steps in the evolution of Pokemon’s production process that has been accelerating over the last few years.

Even though they get to avoid some of the most insidious problems that latenight anime faces, long-running series have issues of their own. One of them is as amusingly obvious as it is inoffensive… until it’s not. Without extended breaks in your broadcast, it becomes much harder to find the right time to update your pipeline in major ways, and even introducing aesthetic revamps that your staff would have to get used to. Which means that, with the passage of the years, you can end up with archaic toolsets holding you back and an aesthetic that no longer fits current trends; though the latter is arguably not a bad thing per-se, the last thing you want in a project with the duty to deliver an episode a week for the next eternity is being bogged down by fundamental inefficiencies.

If you want an extreme example, the last anime to make the switch from cel animation to digital production was Sazae-san, which followed its traditional path until late 2013. That’s nearly two decades after the industry had begun a switch, at a point where it had become so tremendously inconvenient they had no option but finally modernizing the production, even though all viewers were used to an aesthetic that only analog procedures could nail. Incidentally, Pokemon was a bit of a late bloomer in that regard too; having started in 1997 as a cel production, the series had to ride a bit of a sinking ship until 2002 – late Johto, right before Advanced Generation became the first “new season” in Japan – to switch to digital animation, which required some smart maneuvering on their part to soften the reception. Both in technical terms and when it comes to audience expectations, addressing anachronistic elements in a long-running series can be tricky.

In more recent years, Pokemon has done a better job at keeping up with technological and aesthetic trends, but that’s precisely because they’ve settled on a model of constant evolution; their goal being to stay up to date with tech and outright quality improvements, while also delivering change in bite-size chunks that an audience wary of new things is more likely to digest without making a fuss. This attitude hasn’t been a minor policy, but rather the defining trait of Pokemon’s production ever since OLM Team Kato took over the process in 2010, succeeding the studio’s Team Iguchi branch.

While it doesn’t tell the full story, looking at the evolution of Ash’s own design is indicative of how that attitude manifested. For over a dozen years, the show’s protagonist stayed nearly the same, with a minor shake-up once the production went digital. And yet, despite the core staff between Diamond & Pearl and Best Wishes staying essentially the same, the change of management to Team Kato for the latter led to the first design update that truly got noticed by fans all over the globe… other than his mandatory new hat to commemorate each new region, that is. It did away with some of the previous stiffness, and finally granted Ash colored pupils; admittedly a minor change, but one that takes into consideration both the changes in production (digital HD animation) and consumption (higher definition TVs becoming more commonplace). Following that, XY’s new staff opted for a more extensive update of the designs – and even Ash’s body language – that can be best summed up as make him look as cool as possible, which was unsurprisingly well received by the fans who had been looking forward to seeing him kick ass.

Before we get to Sun & Moon’s aesthetic revamp, though, there are more ongoing changes at the studio worth addressing, since this team is doing way more than changing Ash’s looks between seasons; as you might have noticed, it’s common to hear from larger animation production companies about their intent to improve the quality of their work, but less so to see their commitment to it in concrete, effective ways like OLM has been doing. What are those, then? Though the efficiency gains in their pipeline are the ones that people in the team are most thankful about, from the audience’s perspective the greatest improvements relate to the massive increase in dynamism during action scenes.

For the longest time, mainline Pokemon games got away with a fixed camera during battles. That’s slightly changed in modern times, but we’re still dealing with a fairly static affair that doesn’t quite work if you switch to non-interactive media. The Pokemon anime has always greatly benefited from more ambitious action storyboarding, especially by directors like Yuji Asada that excel at spatially complex fights… but those were so taxing that they were reserved to climactic moments carried by the aces of the team, meaning that they couldn’t be had on the regular… despite a certain monster in the staff doing an impossible amount of work.

To address that, OLM has spent the last few years mastering 3D environments and fully integrating digital animation into their regular pipeline, to the point of translating Toon Boom’s documentation into Japanese and encouraging the staff to give it a spin. Their investment didn’t take long to pay off: while traditional background animation is always there in cases where the goal is a more tactile kind of frenzy, 3D camerawork has become the norm for Pokemon. And that has enabled both the team’s aces and animators who only felt comfortable with modest sequences before to step up their game, increasing the scope of the action for the whole series rather than just during climactic moments. Even writers and directors feel more comfortable in an environment like this, since they know that they can include ambitious ideas without burning out the team too much. Now imagine if this increased efficiency was paired with perfectly animation-friendly designs and a joyful animation philosophy…

And so the stars aligned for Sun & Moon. The game that inspired it had, for the most part, a very particular lighthearted atmosphere to it. And thus the anime adaptation, spearheaded by new series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario. Daiki Tomiyasu and writer Aya Matsui, sought to make that feeling its backbone by rooting the show to its setting more than ever. Although Ash and his friends technically still travel for the trials, Sun & Moon is a much more stationary season, trading some of the adventuring spirit inherent in the premise – which the anime arguably doesn’t exploit to its full potential anyway – for a stronger sense of place. Alola is a more sociologically and ecologically coherent setting than we’re used to, with a consistent ethos across its region that makes the allusions to their way of life carry real weight. When Ash invokes the Alolan spirit during the climax of the final battle, that’s not him spouting nonsense out of nowhere – he’s yelling about the philosophy we have experienced for three years, cheesy as it may still be.

To make things even more interesting, that same philosophy deeply influenced the new aesthetic. Even in a vacuum, the heavier stylization of the designs and their more natural posture would be a godsend for the animators, hence why those principles are here to stay in a post-Sun & Moon world too. What’s much more specific to this series, however, are more stylistic decisions like softening Pokemon’s traditionally sharp lines to such an extreme degree or actively encouraging comedic acting like never before. Ash looks more child-like than ever in the season where he spends most of his time at school, and the entire cast (including the Pokemon themselves) is equipped to emote in the joyful way that Alolan residents would. While there’s no denying that OLM wasn’t as careful as they’d been in the past at gauging potential blowbacks – the switch from Ash’s coolest incarnation to this lovely dork was bound to ruffle some feathers – the entire aesthetic feels like the perfect extension of the show’s goals.

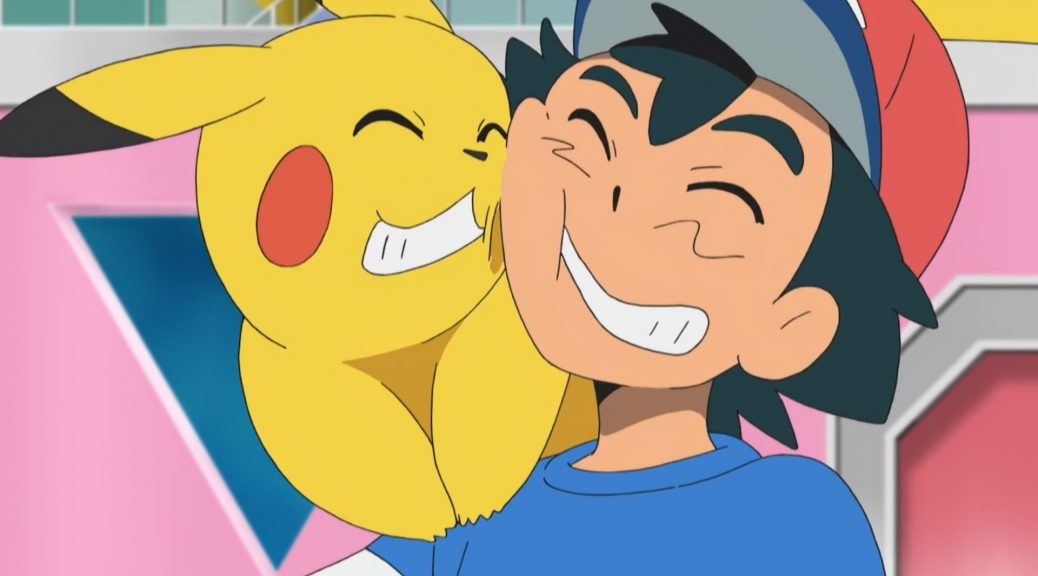

If you want a good example of all those ideas in practice, look no further than the very first scene, which encapsulated what Sun & Moon is all about – in thematic and technical terms, but also in regards to which members of the team embodied those the best. Although Isao Nanba had been in the industry since the late 00s and was already a regular OLM animator, he hadn’t quite managed to stand out… until Sun & Moon’s intro, with its funny character art, shifting expressions that exploited the new malleable designs, plus a very tactile intimacy between Ash and his partner Pikachu.

Nanba found the right environment for him since the beginning of this production, hence why his growth ever since then has been exponential. He began to regulate the looseness of the animation with more expertise and his acting gained articulation in a more traditional way, making it convey the right emotion even when his amusing faces aren’t visible. His contributions to the show’s action – 2DFX in particular – are worthy of note as well, but in the end it was his commitment to making Sun & Moon joyful to watch at all times that summed up why this series was a match made in heaven for animators like him.

In fact, the production fit Nanba so well that by episode #16 he was already making his animation directionAnimation Direction (作画監督, sakuga kantoku): The artists supervising the quality and consistency of the animation itself. They might correct cuts that deviate from the designs too much if they see it fit, but their job is mostly to ensure the motion is up to par while not looking too rough. Plenty of specialized Animation Direction roles exist – mecha, effects, creatures, all focused in one particular recurring element. debut. All of his qualities were in full display there, but perhaps what’s most interesting about it is how it demonstrated the symbiotic relationship between Sun & Moon’s writing and its animation. Most of the episode featured no actual dialogue, as it followed the Alolan starters adventuring without their masters after accidentally getting blasted together. Even though the Pokemon designs didn’t go through a severe linecount reduction in the same way as the human characters, since the concepts are essentially the same, the general approach to the animation still made these creatures more expressive than ever. Knowing that, the team could build entire episodes around non-verbal communication like this, or simply sprinkle tidbits of it to enrichen normal episodes. Countless funny visual gags, foes that came across more imposing than ever, even extra physicality to the action. There’s been so much to gain from the extra expressivity in these creatures.

I’ve stressed out that the aesthetic that enables this wide expression range is inescapably tied to the show’s themes and tone; while the animators benefited from it the most, it’s not as if they went rogue with the visuals, but rather profited from higher up decisions – likely on a director and producer level – during pre-production. That said, it’d be unfair no to talk about designers Satoshi Nakano and Shuhei Yasuda, who deserve a lot of credit not just for how technically accomplished the series is but also for its incredible visual humor. Regardless of personal preferences, the current trend in TV designs towards greater levels of detail can often neuter the inherent charm of animation, most noticeably in comedic sequences. To put it simply, this is the reason why anime still features amusing reaction shots (plentiful in this show too of course) and yet hilarious sequences where those faces are articulated are so rare… except in productions that swim against the tide like Sun & Moon.

Leading this atypical animation effort, not just providing the designs but also in charge of key supervision, we’ve got the aforementioned character designers; plural, in another usual move for Pokemon. Out of the two of them, the one who caught the eye of fans the most is undoubtedly Yasuda, who was promoted to character designer surprising absolutely everyone. By the time Sun & Moon started, Yasuda had only been in this industry for about 5 years and had yet to supervise an entire episode by himself. Even his Pokemon experience was limited, almost accidental; he’d been invited to OLM during by production assistantProduction Assistant (制作進行, Seisaku Shinkou): Effectively the lowest ranking 'producer' role, and yet an essential cog in the system. They check and carry around the materials, and contact the dozens upon dozens of artists required to get an episode finished. Usually handling multiple episodes of the shows they're involved with. Noriaki Suzuki, whom he knew from his early days at AIC, and stuck around for a handful of episodes during XY and XY&Z… even though Suzuki had already left the studio by then. Trusting a newcomer like that with such an important role was by all means a risky bet.

And the risky bet immediately paid off. Yasuda supervised the first episode, confidently exposing Sun & Moon’s identity to the world. No restrictions when it came to character expressions (with Yasuda’s direct intervention in the wackiest sequences), which made the visual gags funnier while also enhancing the reactive feeling of the action animation. Special scenes that weren’t only animated by OLM’s own aces, but also by freelance digital animation stars who have been feeling more at home than ever in Pokemon’s modern iterations. Saying that this first episode was an excellent showcase of the principles of animation doesn’t just mean it’d pass arbitrary tests of squash & stretch and the likes, but rather that it understands the appeal of the medium in a broad way. For a major example, there’s the fact that the simple animation designs allow for richer, denser compositions with plenty of secondary action – like Pikachu burning its hands here – that made the episode, and eventually the whole show, feel more alive.

Rather than the exception that skeptics would expect that first episode to be, it turned out to set the tone for the show altogether, even if it rarely reached those same heights of animation excellence. A great contributor to that consistency was Yasuda himself, who participated as an animation director in a dozen episodes and provided key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. for an even higher number, including many climactic moments. Yasuda even key animated a weekly corner by the name of Eevee, Where Are You Going? that ran for a month, following the Pokemon’s adventures before his path intersected with the main narrative and he joined Suiren’s team. These segments, which featured no dialogue whatsoever, further proved how suited the show’s expressive animation was for non-verbal communication by Pokemon.

It’s important to note that, while Yasuda is undoubtedly talented, he wouldn’t have been able to focus on all these important details if there wasn’t someone to worry about the larger picture. And that someone was Nakano, the other character designer and sole chief animation directorChief Animation Director (総作画監督, Sou Sakuga Kantoku): Often an overall credit that tends to be in the hands of the character designer, though as of late messy projects with multiple Chief ADs have increased in number; moreso than the regular animation directors, their job is to ensure the characters look like they're supposed to. Consistency is their goal, which they will enforce as much as they want (and can). for the entirety of Pokemon Sun & Moon. Their roles in the production were complimentary, starting from their position at the studio; unlike the freelance Yasuda who didn’t have a whole lot of experience there, Nakano had spent his entire career at OLM (on franchises like Inazuma Eleven, Tamagotchi, and of course Pokemon), making him a better candidate to focus on the stability of the production.

When you compare the two’s stylistic traits, this arrangement is also easy to understand. In contrast to Yasuda’s loose, bouncy animation that’s a joy to watch on a moment to moment basis, Nakano’s greatest strength is subtler: the ability to make animation, regardless of how hectic or stylized it is, appear volumetric; his solo endings for Tamagotchi are a great example of the latter, giving actual presence to the creatures with very few lines. And thus he left the immediately satisfying animation duties more in Yasuda’s hands, while the focused on the understated qualities on a larger scale.

By the end of the show, that only left Nakano with time to do hands-on supervision for two episodes. The first one was Ash & co facing his old pals in episode #43, which made Sun & Moon’s celebratory spirit more overt than ever by delivering what fans had been dreaming about for decades; and I mean that down to the impossible production values, making it perhaps the best Pokemon 20th anniversary commemoration altogether. And rather than let that overshadow his next work, his final contribution was #144, the most exhilarating action climax in the franchise’s history. Both of them are dazzling animation festivals, and thanks to Nakano and his team, technically sound ones at that.

Looking behind the scenes on some of the episodes that I’ve been highlighting as particularly excellent, like #16 and #144, reveals another major strength of Sun & Moon: the fantastic guests it has featured more regularly than ever. Although animators of the highest caliber had visited Pokemon in the past, their presence was concentrated on movies and unusual side projects, with the TV series rarely receiving much of that love. And then came Sun & Moon, with Yoshimichi Kameda’s first-ever contribution to the series right in the first opening sequence, as if to send a message to the world; or perhaps, sending a message more specifically to everyone who doubted the warnings that industry legends had professed their love for Pokemon’s new aesthetic… even though they had said so publicly. Unsurprisingly, listening to people in the business continues to be a good way to keep your finger on the pulse of anime.

Kameda’s explosive arrival was the first of many noteworthy guest appearances, all of them adding a unique flavor to the series. Episodes like #97 channeled the sheer intensity of Kosuke Kato and Boya Liang, whereas Nanba’s supervision debut on #16 that we talked about earlier relied on the acting charm of Dogakobo-affiliated aces like Hayate Nakamura and Akira Hamaguchi. Episodes like that prove how welcoming the series was for all sorts of artists, not just on a stylistic level but also because of how comfortable it made them feel with experimentation, as seen by the fact that the episode opened with Yasuhiko Akiyama’s first Toon Boom animation.

Incidentally, Akiyama also got to co-supervise his first episode of Pokemon in the form of Sun & Moon #59, where alongside Yasushi Nishiya – not as integral to the fate of Pokemon’s animation as he’d been in season’s past – he showed a side of himself that fans of this franchise weren’t acquainted with, further expanding the show’s range while he was at it; nothing but adorable animation but with more restraint, emphasizing Mao and Suiren’s childlike innocence via details like their awkward walking. And once again, it was achieved in part thanks to one-off appearances of animators who rarely if ever work in Pokemon – like Nobuyuki Mitani, who animated the intro alongside Akiyama.

At the end of the day, when people think back on the unusually high concentration of external talent in Sun & Moon, they’ll turn their eyes to special episodes like #144. And why wouldn’t they? The final relay with Toshiyuki Sato, Chikashi Kubota, Daiki Harashina, and even not-so-stealthy Kameda is something that right about any TV series wishes they could pull off. A mind-boggling sequence that feels like the only right way for Sun & Moon to reach its peak: a mishmash of styles by freelance artists from all over the industry, all devoted to an earnest celebration of how thrilling Pokemon can be despite having little to no narrative stakes. As far as I’m concerned, the perfect climax.

While I’ll be the last person to devalue an exceptional feat like that, pretending that Sun & Moon’s outstanding animation is simply the product of a lineup of all-stars guests would be disrespectful to the team and miss the point of the show’s actual achievement. While it benefited a whole lot from all these renowned artists making one-off appearances, the lesser-known ones who carried the series on a more regular basis deserve just as much respect. Mind you, that doesn’t just include youngsters; veteran OLM animator Tadaaki Miyata, whose Pokemon work for over a decade had been almost entirely limited to theatrical projects, became a regular member of the TV team for the first time. And that’s precisely the biggest triumph of Sun & Moon as a production: creating a welcoming environment where all these animators, regardless of their personal style and industry cache, could freely make some of their best work to date.

The most emblematic example of this phenomenon has got to be Takeshi Maenami. You’d expect someone with a portfolio as limited as his to be a recent graduate… but the truth is that he completed his animation education at Yoani 10 years ago, before attending cooking classes and helping at his parents’ restaurant for the better part of the decade, as he admitted in the meme format du jour. Though he did a few side jobs in the industry, it wasn’t until 2018 when his career as an animator truly started. And out of all the freelance work he’s done since then, his Pokemon output is by far his strongest work; not only is it the healthiest production he’s landed at, it also made the idiosyncratic rhythm of his animation feel way more at home than in titles with a narrower stylistic range. Despite arriving quite late to the show – his first contribution was in episode #111 – the energy he conveyed in his appearances earned the love of many fans. In the span of a few months, Maenami went from being a technically-newcomer artist barely anyone knew, to becoming the animator whose continued presence fans are celebrating – since of course, Maenami is happily sticking with Pokemon even after Sun & Moon’s end.

A similar sentiment applies to the more in-house side of things, be it OLM employees or individuals with half-binding contracts with the studio. Let me be clear: I have no intention to hide my weakness for Aito Ohashi’s work. Although in technical terms there are more unusual animators in the team, his adherence to his personal style makes him the boldest of the bunch. There is no hiding the fact that Ohashi was destined to become a mecha animation ace whenever he’s in charge of animating any creature reminiscent of robots. His shots of the trainers mid-battle, which use his gorgeous drawings of arms and hands (with 2DFX-like highlights) to channel tremendous energy, are amusingly reminiscent of cockpit cuts in mecha anime. His training in magical girl shows comes across crystal clear as well. And if that wasn’t enough, Sun & Moon found new ways to add to his charm by letting him supervise episodes low on action but with massive amounts of wacky visual humor. Excellence of all kinds on offer, while never abandoning his easily identifiable style. It’s no wonder that animators like him get all the attention.

But again, it’s important to establish that Sun & Moon is a collective triumph, rather than just the sum of the work of its most popular contributors. Every iteration of Pokemon enjoys the rise of new capable team members – that’s practically fate, something that’s bound to happen in a long-running project like this where young artists constantly have to step up their game to make up for the creators who eventually leave the team. While that process is natural, though, up-and-coming artists also benefit greatly from animation-friendly environments like this, hence why Sun & Moon appears to have raised more young prospects than ever; Rei Yamazaki, Takashi Shinohara, Osamu Murata, plus the aforementioned Nanba and Maenami, are just a few of the new names that have begun to catch the eye of fans because of their quick growth throughout this production. And even then, they’re but a fraction of the team that made it possible.

I’ve talked a lot about what makes Sun & Moon different, but it’s impossible to understand its production without addressing something that’s stayed exactly the same. The final piece in the puzzle: the presence of Masaaki Iwane as the team’s ace and workhorse. Usually, those roles would be separate, but Iwane is by all means extraordinary. His 22 years of experience in the Pokemon anime are impressive in and of themselves, but even more so when you realize that he’s been animating its most iconic, climactic sequences pretty much since the start. From the most apocalyptic events to the sweetest downtime (though still ridiculously dense animation-wise), he’s always been there. It’s no exaggeration to say that Iwane has codified what we think of as good Pokemon animation; the broad and exaggerated movements that he’s admitted he uses in an attempt to make the audience feel like the animation is more elaborate than it really is aren’t his personal quirk anymore, but rather something he’s transmitted to generation upon generation of animators, including Sun & Moon’s designer Nakano.

That alone would make Iwane a key figure in the production, but there’s another small detail to consider. Scratch that, a gargantuan detail. Iwane key animated 25 episodes of Sun & Moon all by himself. Which is to say, there’s a 2 cours anime within Sun & Moon with nothing but his own key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style.. On top of that, you have to add his ending sequences, all the contributions he made to special episodes, and his regular help to acquaintances of his like Asada and Yuki Naoi. Then add the fact that he goes back home to animate his own personal Pokemon clips, and hand-craft merch while he’s at it. Now consider that he’s been doing this for ages. Is he human? Allegedly, yes.

Jokes aside, you can imagine how important he’s become to the Pokemon anime, and Sun & Moon was no exception. Long-running series require ways to offload work from their main team on a regular basis if they intend to maintain a consistent level of quality that’ll keep fans happy. The easiest way to do that is outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio., which Pokemon does in spades… though with a bit of a twist; the animation production of 77 out of the 146 episodes of Sun & Moon was subcontracted to other studios, but the series’ healthy schedule allows the in-house team to work side by side with them and bypass many of the usual problems that come with full outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio.. And out of all those assistant companies, the one that handled the most episodes was Cockpit (こくぴっと), a tiny company created by Iwane and his friends in 2016 after the dissolution of Studio Cockpit (スタジオコクピット) where they had met in their youth. And there’s the irony of the punchline: Iwane, the single most influential animator in OLM’s biggest franchise, technically doesn’t belong to the studio.

I wouldn’t hesitate to call the results of everyone’s work some of the greatest in long-running anime production, especially when compared to modern titles that have to scrape by occasional highlights among mediocrity. This isn’t to say that it’s been an animation craze every single week, of course; fatigue was a real worry whenever long demanding arcs happened, as well as whenever the production overlapped with the making of a movie… even in 2019, which had no 2D Pokemon film but still gave extra homework to the team by making them help on the production of Ni no Kuni. But in retrospect, even those more modest moments reinforce Sun & Moon‘s strength: at no point did it lose its identity, due to the smart resource management, the inherent fun of the aesthetic, and that simple, wholehearted dedication to its themes. Even during its rare harsh moments – like the graceful subplot about loss that leads to Litten joining the team and Mao’s situation tackled in multiple episodes – Sun & Moon felt built from the ground up to be Ash’s fun vacation in Alola.

Does that mean that the new reboot, which appears to be aiming for an entirely different style, is doomed to failure? Not necessarily, and once again I feel like people aren’t paying enough attention to the iterative nature of OLM Team Kato’s changes. Even though Sun & Moon‘s artstyle is gone, as it was created with the tone of that series in mind, the degree of stylization of the designs remains – much like the 3D environments weren’t a one-time experiment but rather something the team adapted to moving forward, because they represented a material advantage for the creators. And so, once again, we’ve got exceptional animators celebrating Pokemon‘s aesthetic, with the likes of Maenami already making their way to the production; look forward to his extensive work in the upcoming Lugia fight, and enjoy his opening cut in the meantime. We likely won’t get to experience a range of expression as wide as Sun & Moon‘s, but if these visual adjustments have been done according to the tonal and structural changes, Pokemon‘s 2019 reboot could end up standing on its own too. It won’t win any award to the most inspired title, though.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

Technically, the switch to digital coloring happened during the last “season” of Johto.

https://bulbapedia.bulbagarden.net/wiki/EP261

Thanks! I was a few months off there, fixed it.

Thank you thank you thank you to Pokemon SM for making me enjoy this series again like I did as a kid and thank you for writing something so indepth about it. I love the badass action animation that people keep sharing but you nailed the “something else” that made me fall for SM

Ill be honest I was skeptecal when they showed the designs. I know pokemon has to be kids friendly but it just looked too childish to me. If you showed me a picture of ash by itself now itd still think he looks weird. But when i watched the anime it turned out to be AWESOME. Maybe not perfect (some ultra beasts episodes i didn’t like) but fun almost every week like you said. And to me this visual style feels so much like alola now that i cant imagine the show with different designs now lol

I found this impressive. Good to go…

2002 was also the year Detective Conan switch to Digital so it seems like a pretty standard time to me.