Anime’s Present And Future At Stake: The In-Betweener Problem

Last week, anime creators with diverse backgrounds and standings in and outside the industry joined their voices to illustrate the hellish experience that is in-betweening. This is how the delegitimization of an essential job is ruining lives and putting anime’s present and future at risk.

You can tell that something has been brewing for a long time when a sizable wave of protests hits social media without a specific new event to spark it. Just one animator happening to tag their bitter past experiences as In-betweener’s Hell on Twitter was all it took for this to get traction, quickly prompting folks with very diverse standings in the anime industry to share their stories. High-ranking veterans who have long since moved on from those hellish days, people who left the industry right after joining it because it was unbearable, and everything in between them, all disclosing very personal stories that relate to the bigger point: being an anime in-betweener is awful. And it shouldn’t be.

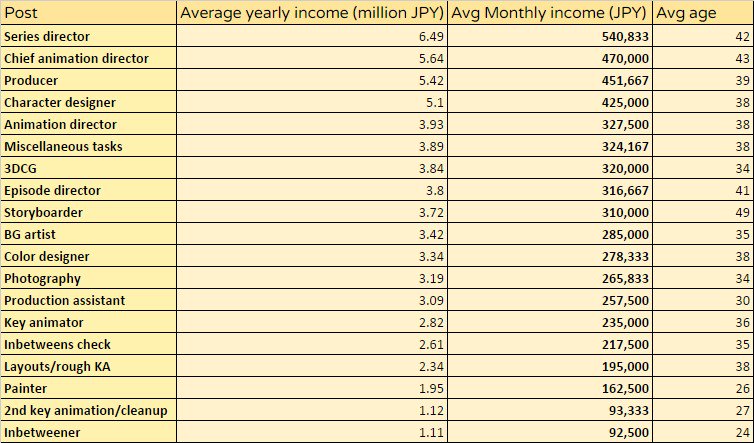

If you know a couple things about the anime industry, those most likely sound like depressingly familiar words. It’s no secret that in-betweeners are usually paid per drawing at frankly unlivable rates that have stagnated around 200~400JPY, or that whenever they receive some sort of salary, it tends to be either insultingly low or downright a scam in its application—sometimes both. It’s equally public knowledge that this causes their work hours to be at the very least equivalent to full-timers… but with none of the benefits. We’ve compiled data on this before, especially as it pertains to young animators, so none of this should come as a surprise on a fundamental level.

And yet, these personal accounts hit hard, rooting all the data and awful tendencies we know about onto actual people’s lives. It’s one thing to hear for years—for decades—that in-betweeners don’t make anywhere near enough money to sustain themselves, and another to see multiple artists who are now at the highest position animators can aspire to explain that their first monthly earnings hovered around 7,500~15,000JPY. And, as many others pointed out, it doesn’t get much better if you manage to stick around after that abysmal start; “There are months where you make less than 50,000[JPY] even if you cut down on your sleep. It’s commonplace to get paid [the equivalent of] 100JPY per hour.” explains one of the many tweets that make it clear the issue isn’t limited to entirely new trainees.

This combination of pitiful rates and strict output-based remuneration means that in-between animators have to put their own health at risk to survive. Many of them explained how much they had to start cutting out on food expenses; “I had so little money that to save on food costs, I used dieting methods to stave off hunger. One time I lived on just coffee milk for a week and came down with a fever,” and “In my time as an in-betweener, there was a period of about 2 years where I lived on flour mixed with water and fried in a pan. My secondary staple was bean sprouts. Every couple of days, I would splurge and eat a single fried egg with okonomiyaki sauce.” are only a couple of examples of the alarmingly common trend they highlighted. As one of them summed it up, “I started thinking about food I wanted to eat in terms of how many drawings they were worth.”

Perhaps even more harrowing is the sleep situation, where tweets like “To think that you would be stuck to a chair working for 36 hours straight…” were aplenty. All-nighters aren’t a rarity, something they’re pushed to do when a project is close to wrapping up, but rather a regular occurrence in many cases. The humble goal of wanting to make enough money to stay alive requires them to put that very life at risk. It’s with a mix of irony and profound deserved bitterness that people contributed to the tag with tweets like “On the 7th night of consecutive all-nighters, the elves finished my drawings. The 8th night, I began to hallucinate voices. The 9th night, I started seeing things, and was sent home by my senpai.”

Countless voices raised to disclose their personal horror stories; many did so publicly, and others that are arguably even more chilling through private accounts that I’d rather not draw too much attention to. While the ones that detail how the job impacted their daily life stand out the most—having to sleep in the studio’s balcony even in the winter would be laughed at for being too on the nose if this were fiction—it’s another kind of anecdote that illustrates the specific problem that in-betweeners face. As an entry-level position in an industry with terribly low standards, it’s frustrating yet sort of to be expected that the job is going to be awful… but it’s worse than that: it’s not even seen as an actual job, and the people who do it are barely seen as humans, let alone as professionals.

When we interviewed many production assistants to shed light on what’s another of the worst positions in anime, it became clear that they’re looked down upon even among their peers; they’re not real creators, even though the second most common route to becoming a director is precisely through production assistance. We’ve continued to see that feeling weaponized from above in the most malicious ways in cases, like the studio 4ºC production assistantProduction Assistant (制作進行, Seisaku Shinkou): Effectively the lowest ranking 'producer' role, and yet an essential cog in the system. They check and carry around the materials, and contact the dozens upon dozens of artists required to get an episode finished. Usually handling multiple episodes of the shows they're involved with. who sued the studio over the near-slavery conditions he had to endure during the production of Children of the Sea. The studio succeeded in dividing the workforce and essentially pitted veteran artists against these overworked management staffers—and as of yesterday, we know they lost the case pretty spectacularly. The labor victory comes with so many caveats that it’s hard to rejoice about it, but seeing this strategy fail for once is comforting.

Similar tactics have been employed to deprecate an already troublesome job like in-betweening, gradually shifting the culture until its current state where they are genuinely not considered animators by a lot of people—including some of those who went through that phase themselves. That obviously doesn’t mean everyone is like that, as initiatives like the hashtag that kicked everything off this time also featured many showcases of solidarity by veterans, but it’s scary how well these tactics work over time. And, since a lot of in-betweening is outsourced overseas now, you can bet that adds yet another level of disgusting dehumanization.

The truth is that we’ve already talked about practices that embody this discrimination. Charging in-betweeners a fee for the usage of their desk if they’re not promoted to key animation roles fast enough sounds nonsensical… until you interiorize that they don’t see in-betweeners as animators at all, that it’s not treated as an actual job despite being essential to the process and requiring a skillset of its own.

Plenty of comments in the hashtag highlight the same attitude—“The in-betweeners were responsible for preparing and cleaning up for the company party, so I ended up working nonstop from noon to the morning after, immediately followed by the next day of regular work.”—and their poor standing within studios, even compared to newcomers in other positions. One of the more telling reports exemplifies that: “I teamed up with several other in-betweeners to meet directly with the studio president to try and get them to take action against a veteran for his flagrant sexual harassment and abuse of power, only to be completely ignored. (The veteran in question ended up leaving the studio a few years later, when it looked like the police would have to get involved after he finally crossed the line one too many times).” Some private musings added that in similar situations, it wasn’t until young staff from other departments raised their voices that problems like that began getting addressed. It’s not the industry’s appalling standards, it’s not your usual case of abuse of seniority: it’s those and a fabricated bias against in-betweeners that’s been getting worse over time.

これの比じゃない人がいっぱいいる

ただの地獄じゃない、阿鼻地獄だ…。#動画マン地獄篇 pic.twitter.com/HYCSX5X4AK— コダ川 (@kodaike_numaji) June 16, 2020

If you thought that such things don’t impact anime’s quality negatively as well, think again. This isn’t only obvious because the in-betweening job on most TV shows is rather dodgy as a result, but because the extremely rare exceptions to the norm have stood as anime’s greatest and most consistent powerhouses for decades. We’re led to believe that the likes of Ghibli and Kyoto Animation rose to greatness magically, that they simply happen to have better animators, when in truth much of their continued excellence is owed to a legitimization of this role that enables the existence of career in-betweeners. Not just experienced in-between checkers that you can find pretty much everywhere, but rather a large percentage of the in-betweening force that’s able to make the choice to stay there because it’s a sustainable job.

While it’s true that in-betweening isn’t a job for everyone, it is a role that some people do feel more comfortable with when given a fair opportunity, be it because it fits their character or technique better. The mantra that there’s no artfulness to it has been repeated so many times that many people treat it as objective truth, despite top animators having highlighted the draftsmanship behind the solidity of the lines and speed of the best career in-betweeners in many occasions too. Even the excuse that key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. is an inherently superior position because it allows the individual artist to determine the feel of an entire shot is starting to crumble, since anime’s increasingly more disjointed production is making it harder and harder for them to realize their vision.

Now, treating in-betweening as a training stage isn’t inherently wrong. Having young artists trace the work of more experienced key animators is a good way for them to come to gain insight on their technique, and a position where there’s a lot of following instructions isn’t a bad choice to begin grasping anime’s often counterintuitive pipelines. But by treating it as a mandatory step—a thesis proven wrong by multiple waves of webgenWebgen (web系): Popular term to refer to the mostly young digital animators that have been joining the professional anime industry as of late; their most notable artists started off gaining attention through gifs and fanmade animations online, hence web generation. It encompasses various waves of artists at this point so it's hardly one generation anymore, but the term has stuck. artists with no traditional training—with such awful conditions, anime isn’t only ruining its present but also its future; their awful situation isn’t addressed since it’s still seen as a temporary non-job, but since most new animators are funneled through it, the industry’s attrition rates are abysmal. If nothing is done about it, anime’s talent is simply going to dry up.

If you can’t recognize the skill at play, you might want to reconsider your understanding of animation and its craft.

That prospect is so scary that the industry has started toying with potential solutions to the problem, but as is also the norm, those come with their caveats as well. Automation offers a lot of potential not just for the future but the present already, as studios like David Production have integrated tools like CACANi into their pipeline to ease the in-betweening workload. At the same time, though, it still requires a lot of human input to lead to satisfying results—and if we keep treating in-betweening as a hellish temporary stage, no one’s going to have the opportunity to get good at it, thus not enough personnel to handle that human input.

Even in an unlikely future where in-betweening is fully automated without impacting the quality, anime would still be getting rid of its only remotely dedicated animation training step. As flawed as it is, immediately pushing all newcomers towards key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. duties where there’s much more room for personal mistakes could lead to an immense disaster. It’s easy to get excited about new tech making artists’ lives easier, but let’s not forget how these things always go. There’s no denying that the digitalization of anime production has expanded everyone’s toolsets and led to tons of QOL improvements, but what have those all been in favor of? The answer is nothing but overproduction, using the removal of traditional bottlenecks to overwork the entire industry. Technological advancements are great, but if they don’t come accompanied by a culture shift, their utilization will never truly help anime creators—if anything, they tend to bite them in the back.

So, what’s that culture shift? It probably begins with the legitimization of in-betweening as a job, likening their status that of key animators for starters; if anyone buys too much into the argument that in-betweeners simply have fewer responsibilities, remind them whose drawings you’re actually looking at in the finished product. This is yet another reason why the current employment model that relies on pretty much nothing but performance-based freelancing can’t be the way forward: it’s only through fairer contracts for all animators that working conditions will improve, because division always gets exploited from above. We’re seeing similar things happen to key animators, where the division of the workload between layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists. and 2nd KA is leading to people on both ends of the spectrum to make less money. Funny how that’s always the outcome!

Every day that this problem goes unaddressed, more material for hashtags like In-betweener’s Hell is created. More people suffer, anime’s future talent gets scared away, and even the immediate quality takes a hit. Everyone loses, except those who benefit from the status quo.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

Are there any tangible ways for me, a Western anime watcher, to realistically make some kind of a difference in the industry?

It would be marginal at best, but from my perspective, you could support studios that have a good reputation for treating their staff well such as KyoAni and Studio Colorido (that I know of, correct me if I’m wrong)!

For this specific problem it’s tricky because in-betweeners tend to be even less visible, so it’s often harder for them to get any traction when it comes to Patreon-style services (FANBOX being the most popular one among animators atm) or even with self-published books, which are the relatively easy ways to contribute I usually direct people towards. One thing I want to point out, though, is that it ISN’T anyone’s duty as an individual to make a difference when it comes to anime’s systemic problems. The industry’s inoperancy has placed an unfair burden on fans who simply can’t address the… Read more »

I see – thanks for that insight. It’s really saddening how hard it is for an individual to address systemic issues, anime-related or not. I only got into anime in the past year or so, but it’s brought me so much enjoyment, entertainment, and, on occasion, personal insight and meaning. As I learned more about the industry, I was really torn because it feels like consuming this media is implicitly encouraging and supporting these terrible practices. That being said, I don’t think I can stop watching entirely. Do you think there are any positive trends for the industry? Something I’ve… Read more »

I think there are positive *cases* more than trends. Like that example you bring up, there are exceptions where those projects backed by sometimes massive international corporations secure a larger production budget, but for the most part, that’s not the case whatsoever. The core staff might get paid better if they’re lucky, otherwise they’re essentially standard projects. A hashtag exposing anime creators’ earnings on Netflix projects a while back made it clear that for most of them, it was standard rates if not lower. So, while there are some reasons for optimism and younger generations definitely feel less willing to… Read more »

Beautiful piece!

In-betweener is hard work!!

Love these kinds of articles. Keep it up

Just wondering how is studio trigger in all this since it’s a well known studio for a good number of animated pieces but I’ve never really heard anything about how they do internally and wether theyre on more of a good working pattern or not ?

And since they’ve also tried to get closer to their overseas audience which is a nice thing that’s not much seen it’d be interesting to know how they’re doing on the inside

Literally just today it was revealed that the same black company union that assisted the exploited 4ºC production assistant had to intervene with cases of unpaid overtime at Trigger: https://twitter.com/magazine_posse/status/1277844313469321222 The studio acknowledged it and promised to do better in a short statement. They also have a pretty well-documented history of being a bad place for youngsters (https://twitter.com/dannyothello/status/1030611533477421056) even though it’s exactly the kind of studio that attracts a ton of excellent fresh talent. Some of them (pretty famous ones even) left within months. They’re not an industry anomaly, and I personally know some people who are very happy about… Read more »

hey, i wanted to ask if you know how much money is needed to to found an anime studio, and how much is needed to found a Anime prodcution company. (im not sure if thats the right term, but i mean the company that takes the order of lets say Shounen jump, and gives it to an anime studio.)

if you have any articles regearding those things that´d be super cool. I really want to know the costs and mechanics and ways how an anime is being produced money wise, and how sponsors come into play

Generally 10 million yen i have visited more than 50 sites of different support and main studios most of them started with a capital of 10million yen

Wow it’s kinda sad to heard that as it’s a well known and respected studio, probably the reason some are still happy to work there,

I think It’s kind the same problem that happens with video games when one is in a dream company and start doing anything to be able to stay there because it’s a kid dream and they still enjoy the finished product but most of the time the problem that come behind are really not worth it

I never understood why Westerners have such a hard-on for Trigger while they were ridiculing the same people when they were still at Gainax…

I guess rebranding does work wonders.

The most obvious solution seems to be making Japanese minimum wage mandatory for in-betweens as a baseline pay, however I’m unsure if that is possible as it seems like it would have been done by now unless there are other reasons. The attitude towards them, well I doubt there is any easy fix for that. I hate in-betweening bing outsourced as it is a great starting point for newcomers, and not all of them will be talented enough to go straight to key animation.