Spring 2021 Anime Overview And The State Of The Anime Industry

It’s time to go over the many interesting offerings in the Spring 2021 anime season to talk about their creative teams, the themes they’re touching on, and their production circumstances—with a lengthy talk about the increasingly more polarized state of the anime industry.

–SSSS.DYNAZENON

–Godzilla: Singular Point

–86: Eighty Six

–Bakuten!! (Backflip!!)

–To Your Eternity

–NOMAD: Megalo Box 2

–Pretty Boy Detective Club

–Other Titles

–But Seriously What’s Up With The Anime Industry

SSSS.DYNAZENON (PV)

Director: Akira Amemiya

Assistant Series DirectorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario.: Yoshihiro Miyajima

Character Designer, Chief Animation DirectorChief Animation Director (総作画監督, Sou Sakuga Kantoku): Often an overall credit that tends to be in the hands of the character designer, though as of late messy projects with multiple Chief ADs have increased in number; moreso than the regular animation directors, their job is to ensure the characters look like they're supposed to. Consistency is their goal, which they will enforce as much as they want (and can).: Masaru Sakamoto

Heroic Animation Chief: Hiroki Mutaguchi

Mechanic Sequence Director: Gen Asano

Art DirectorArt Director (美術監督, bijutsu kantoku): The person in charge of the background art for the series. They draw many artboards that once approved by the series director serve as reference for the backgrounds throughout the series. Coordination within the art department is a must – setting and color designers must work together to craft a coherent world.: Taketo Gonpei

Chief 3DCG Director: Shinichi Miyakaze

PhotographyPhotography (撮影, Satsuei): The marriage of elements produced by different departments into a finished picture, involving filtering to make it more harmonious. A name inherited from the past, when cameras were actually used during this process. Director: Katsunori Shirado

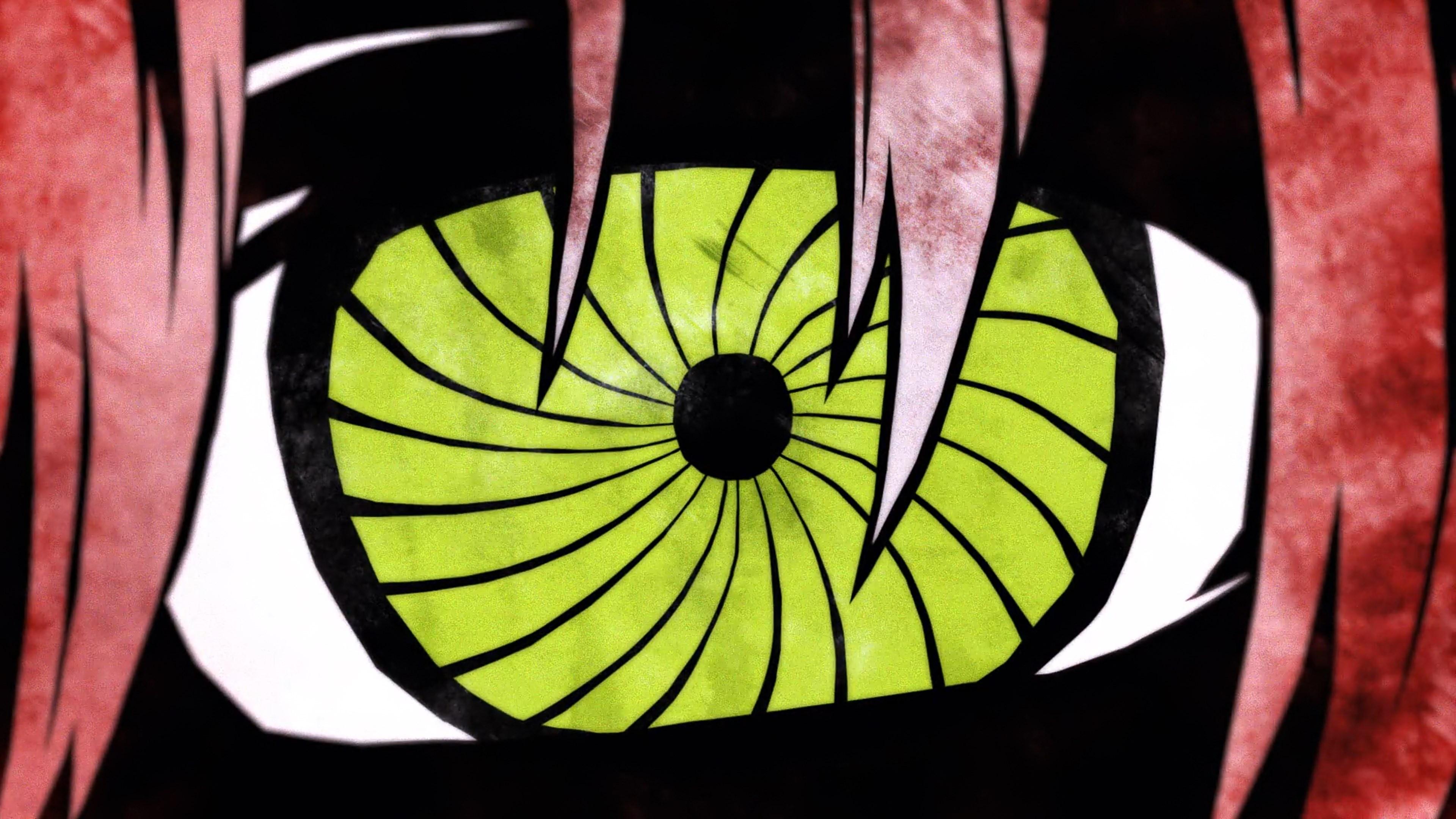

Kevin: SSSS.Dynazenon is a pseudo-sequel to Studio Trigger’s SSSS.Gridman, which was by itself a spiritual successor to their Animators Expo short, as well as a new take on the 1993 tokusatsu series Gridman the Hyper Agent, while at the same time paying homage not just to dozens of toku titles but also to every Masami Obari piece of animation under the sun; and if you’ve seen SSSS.Gridman, you’ll know that the only surprising fact about that statement is that Akira Amemiya dared to follow up the perfectly conclusive ending of his own TV show. But that he has, and after having my doubts about it, I can only say that I’m glad he did.

Amemiya’s heavily Anno-inspired directorial style continues to be some of the most engrossing television you can find nowadays, and the series managed to immediately justify its existence by switching its focus in a very interesting way, while also starting a conversation with its predecessor the likes of which I’ve never really seen. The new ensemble cast is very charming, the slowly unraveling mystery has me coming up with theories that will inevitably be wrong again, and Keiichi Hasegawa‘s naturalistic dialogue in the face of unnatural events continues to be a joy to listen to. On top of that, the show’s production has been finished for months, so you can sit back and enjoy the show without worries about implosions that are so common in TV anime; in the meantime, its creators might sit back and enjoy the viewers’ crazy theories as well. If you want some speculation, but also more behind the scenes reporting to explain how the project’s curious origins are directly tied to Dynazenon‘s themes and focus, you can go read our first set of production notes—you knew we’d be covering this one!

Godzilla: Singular Point (PV)

Director: Atsushi Takahashi

Series CompositionSeries Composition (シリーズ構成, Series Kousei): A key role given to the main writer of the series. They meet with the director (who technically still outranks them) and sometimes producers during preproduction to draft the concept of the series, come up with major events and decide to how pace it all. Not to be confused with individual scriptwriters (脚本, Kyakuhon) who generally have very little room for expression and only develop existing drafts – though of course, series composers do write scripts themselves., Scriptwriting, SciFi Research: Toh EnJoe

Character Designer, Chief Animation DirectorChief Animation Director (総作画監督, Sou Sakuga Kantoku): Often an overall credit that tends to be in the hands of the character designer, though as of late messy projects with multiple Chief ADs have increased in number; moreso than the regular animation directors, their job is to ensure the characters look like they're supposed to. Consistency is their goal, which they will enforce as much as they want (and can).: Satoshi Ishino

Kaiju Design: Eiji Yamamori

Concept Art: Yuji Kaneko

Libo: Godzilla‘s continued success and its ability to draw in new generations of viewers detached from its very specific original context have incentivized TOHO to experiment a bit with their most valued property; it seems like no coincidence that we keep seeing the big radioactive lizard presented in new formats, despite the corporation being very careful with their brand integrity, as corporations tend to be. Singular Point is in fact the first Japanese-made animated television series to feature Godzilla as its central point, which may seem almost unbelievable in its history of nearly 70 years. TOHO’s protective nature in regards to this IP means they are very careful when selecting production partners, and more so if the project happens to be a historical landmark. As the result, director Atsushi Takahashi was appointed as the showrunner—presumably after the massive success of the 2017 Doraemon film which he both wrote and directed—with reputable animation studios BONES and Orange responsible for the hand-drawn and CG parts respectively.

Takahashi’s previous history of working with BONES was key to the developments that ensued. When he decided to approach the kaiju phenomenon with a sense of realism, SciFi novelist and former post-doc researcher Toh EnJoe—who wrote 11th episode of BONES’ Space Dandy, storyboarded by Takahashi—was called by producer Minami with a proposal to provide the scientific research to back the concepts and creatures that’d appear in the series. However, as the project still hadn’t appointed a scriptwriter at the time, EnJoe ended up writing the whole series too.

I do recommend reading his profile for those of you who aren’t familiar with the name; EnJoe’s maximalist writing style backed by academic knowledge is essentially anti-anime in the way it packs information, tying fictional creatures with speculative biology, contemporary sciences, and fictionalized Japanese folklore. If you’re looking for a fresh experience in this medium, this is it! And if that sounds too overwhelming, let it be known that Takahashi balances the content out with humorous situations between female protagonist Mei and her enthusiastic AI assistant, and of course there’s also the reason many people signed up: sweet kaiju action!

Blue Exorcist‘s Kazue Kato—another creator with previous working experience with director Takahashi—drafted the diverse character designs, while industry veteran and BONES regular Satoshi Ishino polished them for animation, then stuck around to serve as chief animation directorChief Animation Director (総作画監督, Sou Sakuga Kantoku): Often an overall credit that tends to be in the hands of the character designer, though as of late messy projects with multiple Chief ADs have increased in number; moreso than the regular animation directors, their job is to ensure the characters look like they're supposed to. Consistency is their goal, which they will enforce as much as they want (and can).. Kaiju designs were provided by Eiji Yamamori, who shares a background at studio Ghibli with Takahashi, with textures for the CG models painted by acclaimed art directorArt Director (美術監督, bijutsu kantoku): The person in charge of the background art for the series. They draw many artboards that once approved by the series director serve as reference for the backgrounds throughout the series. Coordination within the art department is a must – setting and color designers must work together to craft a coherent world. Yuji Kaneko. In case you’re in need for a barrage of extraordinary sakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand., then this anime likely won’t satisfy you beyond the overall pleasant visual style and the ending animation by Norimitsu Suzuki, but fans of Orange’s CG animation are in for a treat with plenty of detailed, lively creatures and bombastic VFX. Be it because of the solid schedule, sheer luck, or a combination of the above, that team is being complemented by a fair bunch of noteworthy storyboarders too, so you can always look forward to the direction being on point. This is not a weak team by any stretch.

The series is currently being broadcast in Japan with a worldwide release set for June on Netflix. The platform’s binge model has always been a source of controversy among anime fans, but I think it’s suitable for Singular Point in particular, at least from what I’ve had a chance to see. Toh EnJoe admitted that he had trouble arranging the narrative structure into 20 minutes long episodes, and the breaks aren’t exactly audience-friendly; so far it feels more like a very long movie divided into smaller chunks rather than a serialized story. Don’t take it as a criticism, though, but more as a part of its unique appeal. If you’ve been looking for a Godzilla incarnation with compelling story and characters, or for the reappearance of more classic kaiju than just the most famous creatures, this might be the one for you.

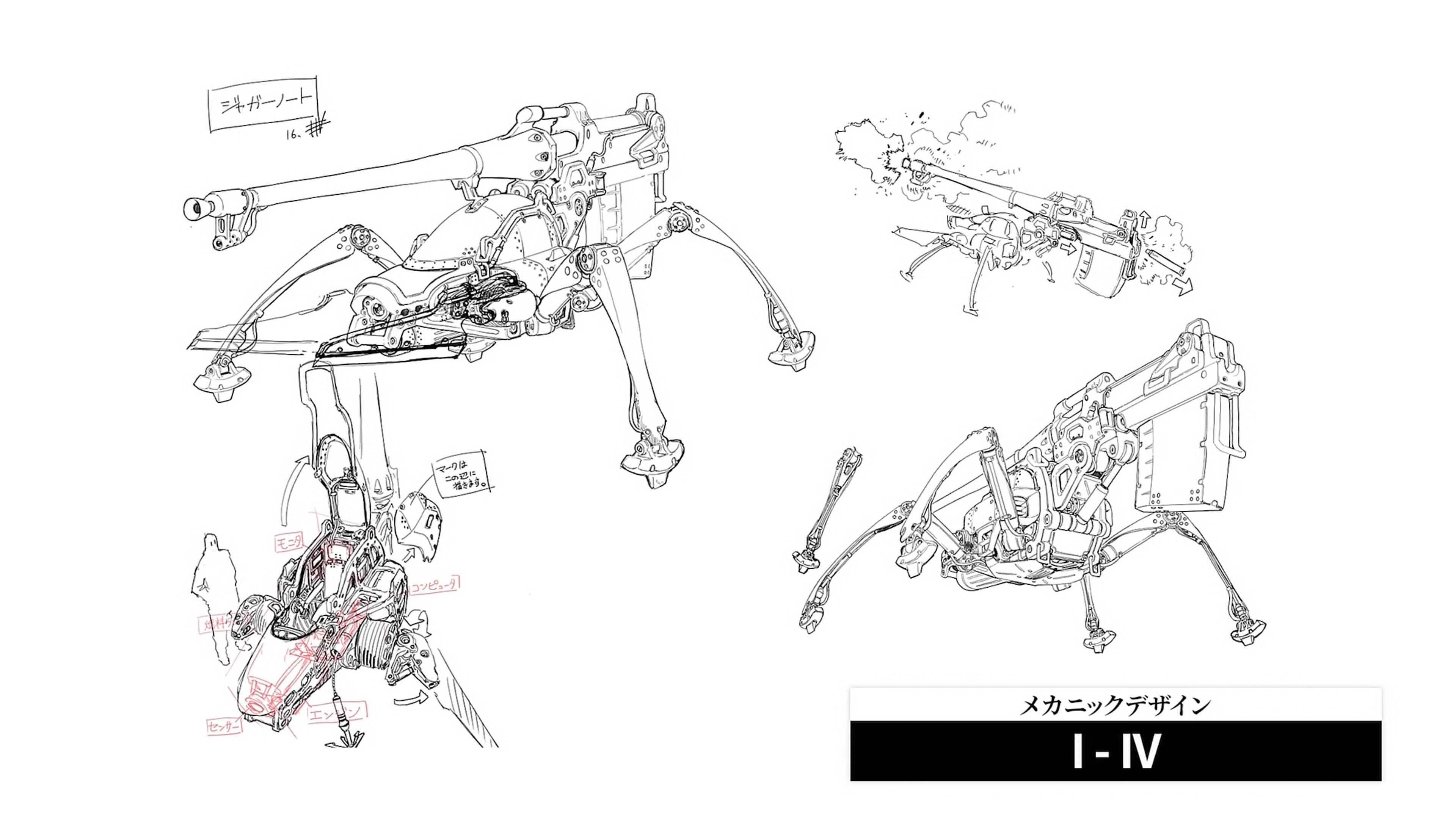

86: Eighty Six (PV)

Director: Toshimasa Ishii

Character Designer, Chief Animation DirectorChief Animation Director (総作画監督, Sou Sakuga Kantoku): Often an overall credit that tends to be in the hands of the character designer, though as of late messy projects with multiple Chief ADs have increased in number; moreso than the regular animation directors, their job is to ensure the characters look like they're supposed to. Consistency is their goal, which they will enforce as much as they want (and can).: Tetsuya Kawakami

Main Animator: Yoshihiro Kasahara

Action Supervision: Ryouta Yanagi, Kengo Matsumoto

Art DirectorArt Director (美術監督, bijutsu kantoku): The person in charge of the background art for the series. They draw many artboards that once approved by the series director serve as reference for the backgrounds throughout the series. Coordination within the art department is a must – setting and color designers must work together to craft a coherent world.: Masanobu Nomura, Yumi Horikoshi

Kevin: Regular readers of the site are likely aware that we’ve repeatedly brought up Toshimasa Ishii as one of the big names to follow in commercial animation over the next few years. His notoriously enthralling style proved to transition well from small-scale efforts to larger projects, so as the first TV anime he’s directing, 86: Eighty Six should have been an immediate cause of celebration. And yet, I admit I approached it with some apprehension. It’s not as if Dengeki Bunko’s hits can’t be perfectly entertaining, but if there’s one thing they often aren’t is nuanced, which is a dangerous prospect when your work borrows WWII concepts and imagery as means of tackling racism and the quick descent into fascism. After watching the anime and reading several volumes of the light—not so much in tone—novels, though, I would say that it’s got surprisingly sharp ideas that this adaptation is capturing reasonably well.

In telling a story about a country that stripped racial minorities of human rights because of an international conflict they had nothing to do with, kicking them out of the inner 85 districts and branding them with the derogatory term that serves as the title, 86 doesn’t stop at the obvious points that racism and fascism are unequivocally bad. The series goes out of its way to argue that the obsession with the aesthetics of liberal democracy is shallow and can easily be co-opted and twisted, to show the effect of propaganda on such a regime over time, and to underline that war is awful but giant mechs are damn cool—even the deliberately shoddy spider tanks that the eighty-six are shoved into. While some viewers overseas will find holes in its depiction of racial tensions, find themselves hoping for more visible diversity, and just shrug at the kinda awkward anime hijinks that happen sometimes, 86 is a thematically sound series with a narrative that’s easy to get drawn into.

There are two important conclusions to draw from this: that Ishii was entrusted with solid material, but also that it wasn’t necessarily easy to adapt. A lot of that nuance comes in the form of narration that the anime was never going to keep, meaning that Ishii—and to some degree series composer Toshiya Ono—had to figure out how to tweak the storytelling to convey as much of that information as possible through the dialogue and the environments themselves. While the results when it comes to the former aren’t always graceful, the way the introduction establishes the Republic of San Magnolia as a creepy ethnostate, artificial even in its cuisine, serves as a showcase of Ishii’s exquisite direction aiding the storytelling.

Ishii has been put in a position where he must be efficient and impactful, and he’s already gearing his old arsenal with those goals in mind. The sleek transitions he’s known for allow him to both underline thematic points and abbreviate all that information he needs to convey; look no further than this literal smash cut with a cream puff baked with nothing but self-indulgence and hubris, followed by the state of the frontlines where you’re more likely to encounter death than sweets. His boards constantly highlight those contrasts, making use of transitions like that to emphasize how close death hovers above the eighty-six. While the anime might not be able to flesh out the source material’s thesis as much due to the differences in formats, when the delivery is this on-point that feels like hardly a problem. As it turns out, that director we’ve been praising for a few years already is pretty good at his job. Who would have thought?

But what about the more mechanical aspects of the production? Though I meant this in the broader sense of the animation and management process, there’s also the fact that this is a mecha anime, which adds more complications to the process. Most of 86’s warfare is conducted by shabby mechs pushed way beyond its specs to pull off all sorts of pirouettes, which is a lot of visual information—texture, volume, agility but also limitations—to convey for right about any mechanical 2D team you could assemble on TV nowadays. The team’s solution was to fully subcontract these tasks to Shirogumi, a CGi and VFX company with a strong pedigree. While their cold photorealism isn’t something I personally feel passionate about, I can accept the argument that it does fit the tone, and their technical skills speak for themselves too.

When it comes to the rest of the production process, 86 has had mixed luck. It’s quite clear that the project is being promoted as a flagship title, with Sword Art Online‘s popularity being the goal they’re openly chasing. This is obvious even when it comes to the staff, with the likes of Tetsuya Kawakami heading the animation design and supervision duties, and of course series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario. Ishii; much like SAO’s Tomohiko Ito, Ishii has acted as an assistant of Mamoru Hosoda—and of Ito himself—before getting entrusted with the big Dengeki title of the current era. Pretty obvious parallels even if you don’t factor in the tone and magnitude of the promotional campaigns.

And yet, it’s hard to say that studio A-1 and perhaps Aniplex as a whole have internally granted it that true flagship status. 86 is in the hands of a rookie animation producer, and the rest of the team that’s gathered around the names I’ve mentioned come from all sorts of run-of-the-mill productions; now this is not to say that they’re not capable of good work, and if anything it’s A-1’s relatively modest teams like Kaguya-sama’s that have left the strongest impression on me lately, but you shouldn’t go in expecting an all-stars team. And for that matter, don’t expect an exceptional schedule either: by tracking the production assistants we can vaguely pinpoint the start of the actual animation process to Q1 2020, which is pretty tight for a fairly ambitious 2 cours anime that was originally slated for that same year. Even with the pandemic forcing a delay, that’s not a whole lot of actual time.

So what does that leave us? A thematically rich story that’s kind of a pain to translate into anime, which is thankfully being handled by a director capable of pulling it off. It’s a project conceived with ambitions of becoming the next big thing, though also lacking the full commitment from higher-ups for the staff to cruise into that goal. The drawbacks are there, but even with those in mind, this is a very interesting prospect.

Bakuten!! (Backflip!!) (PV)

Director: Toshimasa Kuroyanagi

Series DirectorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario.: Seishiro Nagaya

Character Designer, Chief Animation DirectorChief Animation Director (総作画監督, Sou Sakuga Kantoku): Often an overall credit that tends to be in the hands of the character designer, though as of late messy projects with multiple Chief ADs have increased in number; moreso than the regular animation directors, their job is to ensure the characters look like they're supposed to. Consistency is their goal, which they will enforce as much as they want (and can).: Yuka Shibata

Director of Rythmic Gymnastics Practicing: Fumiaki Kouta

Kevin: Your feelings on Bakuten will likely depend on how much you value audiovisual execution over meaty original ideas. This is not to say that its by the book sports series premise is inherently a problem, nor that the fairly archetypical characters aren’t likable—there is a reason why those easily identifiable patterns are in place to begin with. But, even when applied to a sport like rhythmic gymnastics that’s hardly touched upon in this field, Bakuten’s basic concept will quickly feel familiar; protagonist Shoutarou Futaba is an active boy with a natural aptness for sports, but he’s bounced around different activities as a bench player because none truly resonated with him… until he happens to come across a dazzling gymnastics performance by his soon to be teammates.

Neither the narrative nor the character writing appears to be much more complex than that, and yet what I just said sells Bakuten‘s actual experience very short. The show’s ability to sell life-changing moments like that is up there with TV anime’s best offerings, thanks to its excellent sound direction and an animation effort that doesn’t punch above its weight so much as it beats firearms while barefisted. Its success lays not just in the depiction of the sport, a careful showcase of hybrid animation with smart camerawork to increase the wow factor, but also in the highly evocative reactions to that spectacle. When pairing eye-catching pirouettes with equally stunning effects, immediately establishing its visual language with bird feathers and the sky but always iterating on it in neat ways, it’s incredibly easy to buy into Bakuten’s seemingly simple offerings.

Unsurprisingly, Bakuten owes much of this to its series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario.: Toshimasa Kuroyanagi, best known for his ambitious work on The Great Passage and Shonen Hollywood. Over the years, Kuroyanagi has honed a realistic approach to animation that should be unsustainable in TV anime without a powerhouse to support him… and it often is, but that hasn’t stopped him before. Although he had to compromise somewhat in the design front, going for a more anime-ish aesthetic and simplifying robico’s concept art, the first episode serves as a perfect example of the incredibly articulate, down to earth way in which he conceptualizes animation. Since the very start, it’s clear how densely packed with life his vision is, how much care he wants to put into body language and minute gestures, and the realistic solidity that he’s aiming for when it comes to the actual gymnastics.

It’s important to note that Kuroyanagi’s realism isn’t self-serving, nor too cold and analytical. Sure, he does have a penchant for realistic art—just look at how he draws his own characters—and more ambition than he knows what to do with, but he’s found ways to channel those proclivities to his works’ benefits. The thorough acting gives the side characters an immediate visual charisma they’d never have otherwise, and it directly reinforces the writing of the protagonist himself; besides being a cute, well-constructed series of shots, Kuroyanagi confirmed that this scene was meant to casually convey that Shoutarou already had pretty impressive upper body strength. The show’s storytelling may not be subtle, but it sure is graceful, and a lot of it comes down to the confidence it has in letting its thorough animation do the talking.

On top of that, this also reinforces another one of Kuroyanagi’s favorite tricks: contrast. By establishing this curiously realistic normalcy that we rarely ever see in TV anime, the moments of wonder where that’s ditched feel all the more magical. It’s easy to tell that this is one of the main pillars of the project, as it’s been a regular occurrence across different episode directors; each with their own balance, but always with ambitious down to earth acting that highlights the dashes of fantasy. And this applies to the camerawork as well, especially when it comes to the rhythmic gymnastics. While practices use matter of the fact framing, with still cameras that imply objectivity, the actual performances have their camerawork tuned by the one and only Shingo Yamashita, with the dual purpose of obscuring the rough edges and giving the big moments a whole lot more of dynamism.

So, where’s the trick then? How can a modest studio like Zexcs be putting together a truly top-tier sports anime production? An important factor in making this possible is animation producer Kiyoshi Shintaku, who’s behind the studio’s most ambitious efforts; often alongside Kuroyanagi, but also in works like Kase-san or Kurage no Shokudou, where he also dragged the aforementioned Yamashita. Well aware of Kuroyanagi’s ambition, Shintaku made sure to surround him with very talented main staff capable of elevating the whole team’s output. Such is the case of character designer and co-chief animation director Yuka Shibata, with extensive experience in right about every major studio of the 00s, as well as action specialist Fumiaki Kouta, who’s specifically in charge of directing the performances across the whole show.

The final ingredient is a very common one to successful TV anime recipes: time. Bakuten is part of a project to commemorate the major earthquake and ensuing tsunami that hit Japan in 2011, and as such has been a long time coming—its preproduction dates back to 2016, 5 years ahead of its eventual broadcast. The lengthy preparation can be felt in aspects like the gymnastics themselves, as the schedule has allowed them to cooperate with actual clubs and also make extensive usage out of motion capture techniques, providing invaluable reference material and even data to use in the CG shots.

That said, I don’t want people to misunderstand: the project starting in 2016 does not mean that the studio’s been working on it for 5 years, let alone animating it for that long. Just like how me taking a couple days to drag myself to make a call does not mean I’ve spent 48 hours on the phone, you can’t assume that the animation process has a tremendous buffer just because the first talks were ages ago. And this is where things get a bit spooky, because while I know for a fact some episodes have been finished for months, Kuroyanagi has a history of allowing his ambition to melt projects entirely, so even a reasonable buffer could crumble. If you want a scary yet somewhat comforting bit of information, you should know that he absolutely intended to have the first episode’s performance animated with no CG whatsoever; a frankly insane idea to even consider, but the fact that he was able to compromise and still make it such a dazzling scene makes me hopeful about the show’s future.

If you enjoy your typical sports anime, Bakuten’s pointed direction and impressive production values make this a very easy recommendation. And if you think you don’t, maybe give it a try as well, because the confidence that oozes from its execution might be enough to sell you on it—just gotta hope that Kuroyanagi wasn’t too confident about what the team could accomplish!

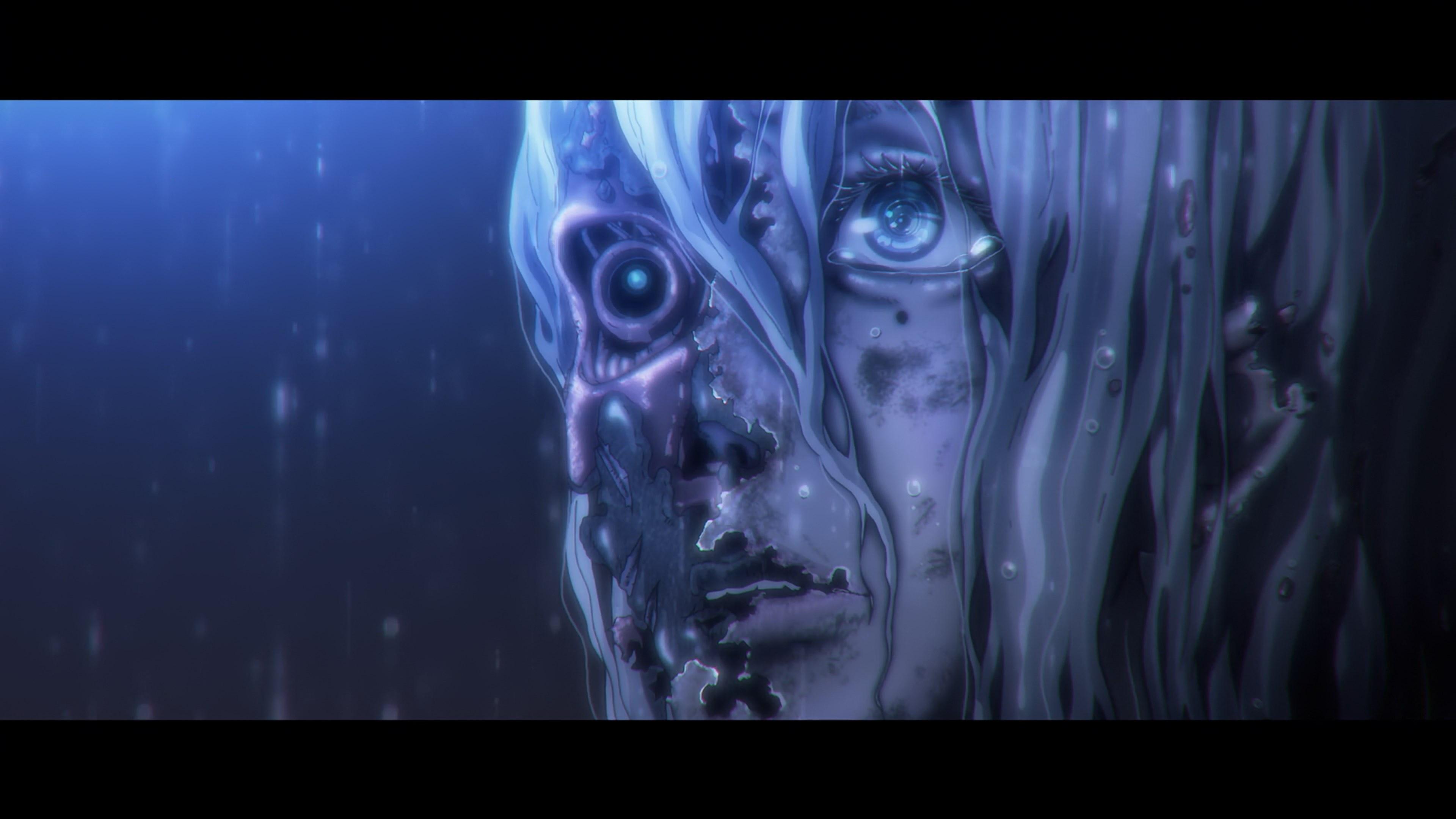

To Your Eternity (PV)

Director: Masahiko Murata

Character Designer: Koji Yabuno

Kevin: It’s frankly insane that a TV anime adaptation of To Your Eternity exists in the first place. You’d struggle to find a series of hurdles more daunting than this ambitious tale across cultures and time, with constant usage of notoriously difficult aspects to animate like large animals and morphing sequences, and with the scary duty of having to succeed Naoko Yamada’s Koe no Katachi as the latest Yoshitoki Oima adaptation—something that’d be easier to forget were NHK not promoting them together so much. And yet, here it is, stunning in some ways, merely passable in others, and admirable all the way through.

While I’m not sure that the staff appreciates having their bar raised to scary highs by all that Koe cross-promotion, the truth is that it’s a great thematic follow-up to Oima’s previous series. Whereas Koe was a smaller story about finding beauty and the will to live together in an often cruel world, To Your Eternity’s vignettes address life itself, whether that beauty in it is inherently tied to mortality, and how one might seek happiness in spite of everything.

I would say that Oima has only gotten better since then: more poignant, and also way funnier—both by improving her already great, quirky paneling and simply by knowing when to add that levity. Very much in Koe fashion, To Your Eternity eventually goes off track in a spectacular way, but it’s an amusing jumping of the shark that somehow keeps the series true to itself, and it happens so late that anime viewers shouldn’t worry about it either way. For now, you’ll be tuning into small arcs that relate to protagonist Fushi in some way or the other—mortality and the lack of thereof, the worthlessness of superficial appearances, the definition of humanity—and then get pretty sad at the end of them all.

Is the anime handling that exceptional source material with the care it deserves, then? I would say they’re doing a more than adequate job for a modest TV production, which is both a commendation of their work and a condemnation of the decision to give such demanding work to a team like this. The art direction is admittedly pedestrian at best, and series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario. Masahiko Murata—who’s so far storyboarded every episode—has taken a very conservative panel by panel, expression by expression approach that’s hardly the most interesting take on the material we could have had. When you consider what they had to deal with, though, corner-cutting like this is perfectly reasonable; keep in mind that the series has already received a major delay, which is always a lesser evil but wouldn’t have happened if things hadn’t gotten very bad in the first place, especially given how little NHK cares about its creators.

On the more positive side of things, we’ve got the animation effort led by character designer Koji Yabuno. Although he doesn’t appear to be sticking around as chief animation directorChief Animation Director (総作画監督, Sou Sakuga Kantoku): Often an overall credit that tends to be in the hands of the character designer, though as of late messy projects with multiple Chief ADs have increased in number; moreso than the regular animation directors, their job is to ensure the characters look like they're supposed to. Consistency is their goal, which they will enforce as much as they want (and can)., he set the tone with his volumetric designs and the incredibly precise animation work in the premiere; especially in the second half that he personally key animated, something you wouldn’t know if you looked at the credits because NHK refused to acknowledge it. Yabuno’s ability to abbreviate detail while still conveying volume is excellent, but this time around he is staying close to Oima’s original levels of intricacy, all while still paying attention to even the most minute secondary animation. This has extended beyond his first episode, with other animation directors also attempting to keep this level of detail in the artwork and its movement, even as beasts battle it out. The greater clarity in the framing of the action, and the visceral appeal of seeing Fushi morph between forms in a bloody battle might be the points where it’s clearest that this anime can add something to the already excellent source material.

While the circumstances are far from ideal, this is a valiant effort to bring To Your Eternity to even more people, and it’s hard not to respect that.

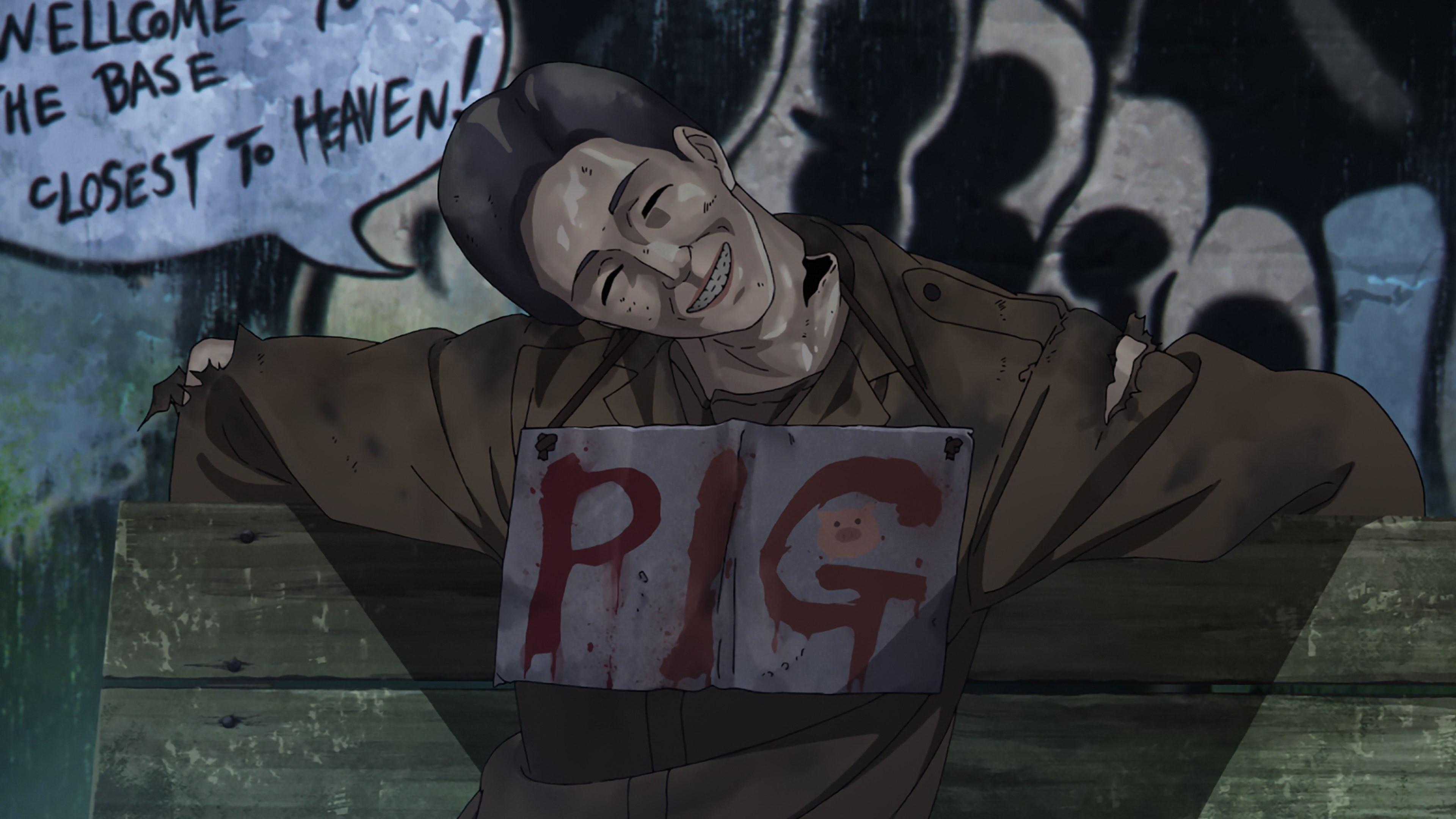

NOMAD: Megalo Box 2 (PV)

Director: Yoh Moriyama

Character Designer: Ayumi Kurashima

Chief Animation DirectorChief Animation Director (総作画監督, Sou Sakuga Kantoku): Often an overall credit that tends to be in the hands of the character designer, though as of late messy projects with multiple Chief ADs have increased in number; moreso than the regular animation directors, their job is to ensure the characters look like they're supposed to. Consistency is their goal, which they will enforce as much as they want (and can).: Naomi Kaneda, Kenji Hachizaki

Art DirectorArt Director (美術監督, bijutsu kantoku): The person in charge of the background art for the series. They draw many artboards that once approved by the series director serve as reference for the backgrounds throughout the series. Coordination within the art department is a must – setting and color designers must work together to craft a coherent world.: Jirou Kouno

Kevin: Megalo Box has been one of the most interesting anniversary projects since its first stages. Yoh Moriyama, a trustworthy designer with essentially no directorial experience, was given the heavy responsibility of following up the classic among classics Ashita no Joe for its 50th anniversary. Asked to put together a sequel, spinoff, or something with a tangible link to the original, he did… none of those things. Megalo Box shaped up to be a beast of its own; one that picked up some thematic threads from the original, with its fair share of references to it in the background, but at the end of the day a perfectly standalone experience that intertwined gritty personal stories with broader social commentary.

Moriyama’s storytelling made use of the tools he was most comfortable with: design work. It was the setting, derived from his stunning concept art, that made the social chasm in the world so clear. He personally underlined the gap between the protagonist’s scrappy gear that he ditched to become Gearless Joe and the highly advanced technological marvels his foes used. Props, outfits, other mechanical gear, even the logo itself—Moriyama was directly in charge of designing many of the elements that did the talking about the show’s themes.

This remains true for this second series. Moriyama is reprising not only his role as director, which means that he’s also back as a designer, because the two appear to be inseparable roles to him. Years have passed within Megalo Box’s universe, and the once champion Joe is now Nomad, a tortured soul who wanders around to escape the traumatic past hidden by this timeskip. This gives the narrative an even grittier tone, but that doesn’t mean its priorities have changed, and once again it’s Moriyama’s visual motifs that embody that best. It’s now a bird, a meaningful symbol to an immigrant community he came across as they were threatened with eviction, that occupies even the show’s logo. Once again, a seamless fit between writing and design; that’s what directing means to Moriyama.

What about the team that surrounds him, though? One of the reasons the original series hit so hard was precisely that: the impact of the animation, never too preoccupied with kineticism, but always sturdy and packing a literal punch. Although Nomad isn’t as extraordinarily fortunate of a production, so far I would say that it’s hitting the exact same notes. The addition of Ayumi Kurashima as character designer could have been a step towards making the animation more flavorful, but in the end she’s not sticking around to supervise it… which is hardly a tragedy, as Naomi Kaneda and Kenji Hachizaki are rotating as chief supervisors to ensure thorough solidity to the art. Given how well this style fits the series, I can’t fault them for not trying to reinvent the wheel.

Another aspect that hasn’t changed but is worth highlighting is the overall approach to the compositing, as I’ve noticed people asking why the show looks so blurry once again. The short story is that the footage is deliberately “damaged” in a variety of ways. Why do that, though? Given how tenuous he kept the links to the original Ashita no Joe, Moriyama wanted something tangible to give Megalo Box an old-school feel and thus keep the balance between new and old. Initially, he considered applying a lot of digital grain as it was, but after thinking that would be too harsh on the eye, he added other steps; heavy filtering on the linework to make it appear thicker and with more texture, having animators sometimes draw in a quarter of the sheet rather than the full thing, and most importantly, the downscaling and upscaling of the footage after exporting it.

I’d be lying if I said there are no drawbacks to this approach. For starters, the result isn’t exactly authentic to the look of old anime—it’s more like a poor old release. By blurring the backgrounds, they also hurt the environmental storytelling Moriyama does so well, and sometimes it introduces purely technical problems like aliasing. And yet, I can’t bring myself to complain too much about a director making such a bold decision with a clear goal in mind. If this is the price to pay to get Megalo Box, it’s more than worth it; even more so now, as Nomad has somewhat toned down the intensity of that damaging process.

Pretty Boy Detective Club (PV)

Director: Hajime Otani

Assistant Series DirectorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario.: Kenjirou Okada

Character Designer, Chief Animation DirectorChief Animation Director (総作画監督, Sou Sakuga Kantoku): Often an overall credit that tends to be in the hands of the character designer, though as of late messy projects with multiple Chief ADs have increased in number; moreso than the regular animation directors, their job is to ensure the characters look like they're supposed to. Consistency is their goal, which they will enforce as much as they want (and can).: Hiroki Yamamura

Main Animator: Nagisa Sekiguchi, Ryo Komori, Tsutomu Shibuya

Art DirectorArt Director (美術監督, bijutsu kantoku): The person in charge of the background art for the series. They draw many artboards that once approved by the series director serve as reference for the backgrounds throughout the series. Coordination within the art department is a must – setting and color designers must work together to craft a coherent world.: Tomoyasu Hosoi

Kevin: Pretty Boy Detective Club isn’t only a descriptive title when it comes to the content of the series, but also about its order of priorities. First and foremost comes the beauty, an adoration of aesthetics that just feels right coming from a writer like Nisioisin, so clearly in love with the form of his own prose. And what is that beauty applied to? Well, of course, boys; a charming cast who lives true to their principles, presented with the most graceful adaptation of Kinako’s designs we’ve seen in animation—all thanks to the versatile Hiroki Yamamura. And that’s when the detective club comes into play, as mysteries unfold and get solved with a fair share of camaraderie. No matter how you look at it, this is a Pretty Boy Detective Club.

And no matter how you look at it, it’s also Ouran High School Host Club’s cousin; casting Maaya Sakamoto as the female protagonist who quickly ends up dressed in more masculine fashion might have been a bit too on the nose, but having such a clear point of reference is admittedly helpful. The connections with Ouran run deeper than you might suspect: while Hajime Otani and Kenjiro Okada are no Igarashi, the SHAFT style they’re iterating on draws from the same Dezaki school as him, so the direction has a similar farcical vibe that feels like a great fit for a bunch of kids rambling about aesthetics.

Now, the show isn’t without flaws and incongruences. The aggressively gaudy indoors art direction is completely at odds with that sense of beauty, for one. Can you really expect thoroughly polished work from studio SHAFT, though, especially now? It’s no secret that they’re in a messy position that demands they figure out who they are again; much of their key talent left the studio, entire new departments are being built to fill that space, and we’re seeing clashing currents of young in-house talent versus veteran outsiders fight for the spotlight. If you can overlook the rougher spots caused by that strife, which I’m sure that its characters would consider the beautiful thing to do, Pretty Boy Detective Club is a pretty fun time.

Other Titles

- There are some sequels we’ve skipped over, not because they lack in quality or interesting points to highlight, but rather because they’ve stayed too perfectly consistent. To say much more about them. Moriarty the Patriot Part 2 is still a lavishly produced—the art direction alone is worth the price of admission—quirky yet elegant fuck you to capitalism and related woes, while HeroAca Season 5 is… well, HeroAca; still produced with a ridiculously large buffer, still not as adventurous as greedy fans would love it to be, still capable of putting back to back thrilling action episodes that put most anime of its ilk to shame. And if you liked Zombie Land Saga, I see no reason why you wouldn’t enjoy its sequel. Unless you have to work on it, in which case you might have some words with MAPPA about its awful schedule.

- My most enthusiastic shout-out goes to Super Cub. Not necessarily because it’s one of my favorite shows of the season, which it absolutely is, but because it’s so quiet that it would never scream for attention by itself. Tojiro Fujii’s understated atmospheric direction and the surprisingly attentive writing that it confidently elevates have no business painting the headspace of an introverted protagonist with such elegance for a show that’s essentially a Honda commercial, but I’m very glad they do. Despite the very limited resources they’re working with, you really shouldn’t miss this one if you enjoy quiet anime.

- While the involvement of high-profile names such as the writing duo of Re:Zero‘s author Tappei Nagatsuki plus Chaos;Child‘s Eiji Umehara and WIT themselves might have made you think that Vivy: Fluorite Eye’s Song was going to be a massive flagship production, the truth is that this is a bit of a side project for the studio. With that in mind, their work is perfectly reasonable, with Nagatsuki in particular doing what he does best and WIT adorning the relatively modest effort with some of the most thorough make-up animation they’ve done to date. The studio is trending in a pretty exciting direction, and even though Vivy won’t set the world on fire, it’s still a pretty fun watch.

- Kyoto Animation staff has affectionately referred to Minidora as season 1.5 of Maidragon. Despite being a short series they’re releasing completely for free, they’re putting enough effort in it that it can easily stand toe to toe with the main series—be it its animation, background art, or the comfy cuteness that’s characteristic of their adaptation.

- Odd Taxi is the best show you’re not watching, one that I’d have given a major spotlight to had its execution not been very rudimentary for the most part. Much like Megalo Box, Odd Taxi is clearly a designer’s anime—the major directorial debut for an artist like Baku Kinoshita, who’d spent years coming up with the crazy ideas that have eventually shaped this show. Come for the funny concept, stay for the excellent dialogue, get addicted to it because of the thriller narrative, and please join me in theorizing about the cast in the furry anime not actually being animals.

- Meanwhile, Mars Red is a fascinating title that marries its stage play origins with appropriately theatrical direction—most visibly through its cinemascope aspect ratio, but also in the farcical staging, and even the audio as the play’s original author is acting as the anime’s sound director. It’s got a striking, very deliberate aesthetic, and mystery that might have been interesting even with plainer delivery. Why didn’t we give it a bigger spotlight, then? Well, personally I’m running a bit low on enthusiasm for studio Signal.MD, after they refused to pay an animation director for their FGO movie because they deemed the work they never gave him enough time to do to be unsatisfactory. Once they got called out on it, they definitely didn’t retaliate by snitching to the cops that he was driving with no license, getting him actually arrested. Isn’t anime fun?

- You know what actually is fun? Pulpy anime that’s stylish in the most basic of ways, like Jouran and its heavy contrasts accompanied by crude ukiyo-e flourishes. It’s the kind of show that feels a pathological need to end episodes with a cliffhanger, which only adds to its appeal as a serialized B-movie.

- Shadows House is a fantastic series by the duo Somato, whose horror coated in cuteness won me over with the short series Kuro, about a girl and her maybe eldritch cat. They excel at emphasizing the subjectivity in horror, and with Shadows House, they succeeded at crafting a much larger narrative confined in a still small setting. Unfortunately, its anime adaptation oscillates between being alright and actively missing the point—color design that allows an anime about shadows to have them accidentally blend into the background?!—so my honest recommendation has to be for the manga and the actually excellent ending sequence, directed by Akudama Drive’s Taguchi. That man’s on a roll!

- Fairy Ranmaru is essentially Boueibu’s cousin, sharing a lot of its DNA but raised in a different household; while Shinji Takamatsu’s direction for its predecessor was always coated in irony, Fairy Ranmaru is in the hands of Masakazu Hishida and their KinPri pals, which means very serious commitment to the most ridiculous extremes. Hishida and company, all of them with plentiful experience directing crazy kids anime, are making a magical girl show that just so happens to star fairly naked hot boys as if that were the most natural thing in the world—and why shouldn’t it be! It’s all supported by surprisingly inventive design work and a solid animation schedule too, which always makes things a more attractive prospect.

- If you’re the kind of person who’d enjoy Nagatoro-san, you don’t need me to mention it at all because you’re already watching it and it probably has become your favorite time of the week. It’s a perfectly reasonable adaptation of a type of material that doesn’t always translate well into longer-form animation, so let me just point out that the opening and ending are excellent examples of repurposed assets. In an era where animators are so overworked, having people around who can materialize cool OP/ED pretty much out of nowhere is starting to become very valuable.

- Much like its predecessor, Mewkledreamy Mix is a very charming show that barely anyone overseas will watch. It represents Sanrio’s magic at its peak: consistently adorable, occasionally insane, and perfectly fine-tuned to make you smile every week. While the drop in production values in between seasons is noticeable, I don’t think you can fault it for not being JC Staff’s strongest work two years in a row, and both the delightfully fast pacing and its eye-pleasing design work have only gotten better since then.

- I was going to dedicate kind words to Cardfight Vanguard overDress, and then it had to take a break for production reasons, so I’ll refrain to avoid jinxing it any further. As someone who only occasionally dips into card game shows, though, this feels like a very fresh entry in the series!

- Also Precure is good, but you knew that.

- Since Uimama continues to be involved with anime that are visually and also morally ugly—and this is coming from a childhood friend respecter—the vtuber anime (?) award of the season goes to the second season of LeverGacha Daipan, which only just started with a reminder that Taiko no Tatsujin games are the best. Sorry, Shinkalion Z. Subtle environmental clues tell me that Yashikizu wants people to treat the cool new set with care, so I hope the exact opposite happens.

But Seriously What’s Up With The Anime Industry

Last season we ended our overview with a lengthy explanation of the state of the industry. It felt necessary, as fans had noticed that many high profile or otherwise promising titles had piled up in the usually quiet winter of anime, but assumed that it happened in spite of the awful circumstances that the pandemic made worse, rather than because of them. Despite remote work being technically doable in an industry with increasingly more digitized workflows and where most animators are freelance anyway, anime’s tendency to work with very little buffer meant that the losses of efficiency a global pandemic was inevitably going to cause would be deadly for tons of projects. And they were… or would have been, in some cases.

A lot of anime is treated by its own producers as completely disposable, to a degree that’s frankly disgusting. But a lot doesn’t mean all, not even most of it; mind you, this just means that they’re actually invested in those titles, not necessarily that they care about its creators nor their artistic achievements. So, what happened to all those titles they had some faith in? Rather than being unceremoniously pushed off a cliff in 2020, they were delayed—most of them quietly so, because corporations just refuse to be honest about behind-the-scenes matters. And this is how we got to this weird start of 2021, where not only we have a ton of anime, but also an unnaturally high concentration of titles that feel like people actually believed in them, from top to bottom.

As nice as that sounds, the side effects are clear. Many delayed titles were already in such a rough spot that an extra 3-6 months wouldn’t necessarily fix their issues, and the ones that proceeded as planned still had to deal with how complicated it is to coordinate a large group of creators right now. Unfortunately, last season embodies just how unstable the situation has become. We highlighted that by bringing to attention the issues that Wonder Egg Priority and SK8 were facing. For the good and for the bad, the former was a once in a decade production, one that crashed so bad that it’s still not over. But while that one had warning signs we highlighted since the start, even safer bets like SK8 ended up becoming an indescribable mess—that one left even its staff puzzled as to how things got that bad despite the ample schedule. Add to that the equally rough state of certain massive sequels, and this paints a picture of an industry completely in shambles.

The reason we’re back to talk about the industry at large again isn’t a simple I told you so, though, but rather to bring up a sentiment that’s been brewing among anime creators—the idea that schedules are actually getting better. This is seemingly ridiculous idea has been echoed here and there across the industry; a minority opinion for sure, but one vocal enough that it has to come from somewhere, right?

One of the most visible voices to mention that the way anime is made is changing for the better is Shinji Takamatsu, who’s been in the industry since the early 80s and whose directorial career spans nearly 30 years. After doing a whole lot of mecha work at Sunrise, he specialized in directing irreverent comedies produced without all that many resources; Gintama, School Rumble, Daily Lives of High School Boys, Sakamoto-san, Ixion Saga DT, Boueibu, Grand Blue, RobiHachi, it’s clear what his brand has become. All while confirming that he’s been making a new show that should premiere in 2022, Takamatsu said that it has become more common than ever to have shows fully finished by the time of the broadcast, in a way that—and he meant this in the most positive way possible—it doesn’t feel like TV anime anymore. Could it be that the solution to TV anime’s woes that people often point at is something that we’re already trending towards?

To some degree, yeah, but with caveats big enough to fit dozens of disastrous productions every single season. It’s important to note that anime finished before their broadcast begins have existed for decades as a rarity, much like pre-scored titles and many other non-standard approaches. And yet, it is true that there have been more instances as of late, for reasons that should be easy to understand. Streaming platforms, for one, tend to want their material ready as soon as possible; this doesn’t just apply to Netflix, or even to large scale decisions like wrapping up a whole production before its broadcast—even weekly deadlines are stricter on streaming platforms than on TV, often leading to them having different masters with varying degrees of polish.

Another major reason, which often overlaps with the previous one, is that titles funded or otherwise majorly aimed at audiences overseas have special demands. Be it wrapping up a show early so that it can get safely approved in China, or simply having the materials done to dub it in English, it’s become relatively common to plan ahead with those situations in mind. There are instances where this leads to indirect scheduling improvements for some titles too; a specific project might not be slotted for an international release with those requirements, but if that team has one such project slated for later, it can benefit from the need to get things done early so the staff can move on. This, alongside the fear that the pandemic has instilled in many companies, is slightly shifting the serialized anime culture to normalize finishing unrelated small projects like Takamatsu’s early as well. So yes, what he’s saying holds some truth.

Even though Yuu Yoshiyama‘s Cure Flamingo transformation sequence had already premiered a month beforehand, she pointed out that this sequence she drew the layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists. for in Fairy Ranmaru was actually her first henshin—simply because the latter’s schedule was so ample that she’d been given the job well over a year in advance.

But of course, that’s only part of it, and a small one at that. For every project that gets pushed ahead so that it can be wrapped up early, a couple more are effectively sentenced to death and starved for resources. The ability to wrap up anime productions early should be a sign of things going well, but by imposing it without addressing the root problems like overproduction, you’re at best only applying a small bandaid to an open wound—and at worst, you’re infecting it.

It’s important to remember that there’s a clear precedent of a sector of the anime industry that was once healthier and is now in trouble because companies burst out the floodgates: theatrical anime. Distributors realizing there was a lot of money to be made from latenight spinoff titles and projects by those same teams have led to a mess that resembles TV anime too much; way too many titles making it to theaters, with a decline in quality that is easily explained by the hellish TV-like schedules. There are signs that similar things are happening to anime commissioned by streaming platforms, which are very much on the rise too. The fact that Science Saru of all people turned in a non-functional production like Japan Sinks 2020 should have been a wake-up call, but as usual, corporations feel no need to listen to such things.

At the end of the day, we come back to an idea we’ve brought up before, including in the previous industry overview: the polarization of anime productions, especially serialized ones. There are indeed more chances to able to comfortably finish a project ahead of time—be it because it’s heading to a streaming service overseas, or because you got lucky otherwise. But at the same time, there are also more, deadlier bullets in this scary Russian roulette. As last season unfortunately proved, we’re seeing one historically messy production after the other, and that won’t change until the real issues are addressed.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

>by tracking the production assistants we can vaguely pinpoint the start of the actual animation process to Q1 2020

Maybe i had misconception but isn’t that a enough time for a split cour if they started animating back then ? unless you means they only had the script finished at that period and was just starting with storyboard ?

By the point where the PAs would switch to it, the storyboards for the first episodes should be done, but 6~8 months for a relatively high profile 2 cours series (even if split) is pushing it pretty tight; keep in mind that given the ampler time allocation given to early episodes, that would only lead to a handful of episodes at the very best finished before the broadcast. So really, it makes sense that it ended up getting pushed back an extra 6 months when the pandemic hit, because it was already in a situation where it couldn’t afford problems… Read more »

This is pretty depressing

Personal I think the flow of story and dialogue seems quite forced and rigid compared to light novel. Like I always feel something akward with 86 flow like scene shifting is very noticeable. Kinda dun like the style of directing. Well that just my personal preference.

Interesting, because I actually think it’s doing a fantastic job at threading together the two main POVs with some very snappy transitions between the two – especially when Ishii himself is storyboarding. It’s definitely not going for a natural approach, so if you don’t like being able to feel the director’s hand, then I get being put off by it. That’s the thing with flavorful directors though, it opens up the possibility to not like their noticeable idiosyncrasies. Even in cases where I’m not a big fan of their style (again, not the case for me here) I still do… Read more »

“The fact that Science Saru of all people turned in a non-functional production like Japan Sinks 2020 should have been a wake-up call, but as usual, corporations feel no need to listen to such things.” As much as people claim Devilman Crybaby was one of Science Saru’s better shows (which I feel is debatable), it seems to have the same issues as Japan Sinks, so maybe it’s just an issue when it comes to some companies working with Netflix? I mean Production I.G’s B the Beginning was frontloaded then dropped like a rock quality-wise after the 4th or 5th episode,… Read more »

I don’t think it’s necessarily their fault nor an inherently flawed model. Sure, you have an early deadline, but that one gets set with more freedom – no need to stick to seasonal patterns, they drop enough money in them that there usually aren’t cross-media obligations. But it’s obviously no panacea either, and when projects overlap (which they will when everyone produces this much stuff) then that early deadline can start looking a lot scarier.

(As to how they choose their content, that’s no secret, it’s all algorithm-based and that’s gross.)

I meant more like how did they approach the companies they did. I.G and Bones I get, Sublimation and Zero-G I don’t.

Yes, hello, I’m from the people who enjoy Nagatoro association, we are having a pretty good time, thank you dear Kevin! I wanna say that the series also does a pretty good job at being… pretty good. It had its fun smears and fun noodly arms and from time to time I catch it having its characters go through acting progressions in a single cut, which is… not groundbreaking or reason to open any champagne but definately a nice thing to see. And I feel in general it’s done a good job at not sucking. Otherwise I feel that maybe… Read more »

Molcar’s ultimate thesis was that humanity is foolish, so I’m inclined to forgive them for any people they might have killed. Which is a lot. Must have deserved it. Also I wouldn’t worry too much about Iruma-kun, especially not because NHK stayed too quiet about it. They’re notoriously bad at promoting their own titles, to the point that some teams have tried to go rogue and promote their work themselves since NHK couldn’t be assed to.

While I’m surprised there was a good deal more good anime to watch this season than I was expecting, anime industry talk always leaves me helpless since I’m not entirely sure what I could help do about it besides waiting on the industry in Japan to resolve itself. Thanks for another banger of an article, kViN.

Kevin I’m sure a lot of us would like insight on Odd Taxi’s production. It seems it is being handled by a lot of people making their debut and yet it has great sponsors. I hope you do write about it someday.

What would you say about Shaman King? With someone like the director of SDS season 2 on board, I thought that it would be great, at least in the visual department. So far tho, the art has been good, but I don’t think that I’ve seen a single impressive cut so far. Is it’s production also facing some issues? And the pacing is also looks really shaky.

Don’t think it’s facing more issues than right about anyone is at the moment, it feels more like a relatively modest production geared towards stability. Besides the character art staying consistently polished I’d say it also has very easily above par results when it comes to the compositing (or rather lighting specifically) and the palette, stays very clean but still gives a specific flavor to each setting. As for the pacing, yeah, that’s a more fundamental issue they’re dealing with. Sort of related: a certain very popular animator/director put the show’s opening sequence on blast, just ruthless dragging of its… Read more »

5 years, 10 years, 15 years…. how much longer can this industry last with such hellish production schedules and low pay? Eventually, the older generation will quit due to age or they just can’t take the BS that corporations put on them and add that I assume the younger generation either quit early or don’t even bother getting into this industry. Just how much longer do you think this industry has? I hate sounding grim but this seems like the future we’re heading toward.

Hey can anyone please shed some light on where that last picture is from?

That’s an instance of make-up animation on Vivy: Fluorite Eye’s Song!

When you say “by tracking the production assistants we can vaguely pinpoint the start of the actual animation process to Q1 2020”, how were you able to do this?