A Masterclass In Illustrating A Singular Worldview: Sonny Boy And Shingo Natsume

Sonny Boy is an anomaly in commercial media, let alone as a TV anime: a fascinating creator given a blank cheque that he cashed in to explore his philosophical views, mixing cultural touchstones and personal musings into a unique sci-fi story, and tweaking animation production norms to illustrate a singular worldview with unmatched cohesion.

Shingo Natsume is a lucky director, and we’re just as fortunate of an audience that he is. This isn’t to say that he hasn’t earned his position, of course, but the range of registers and formats that he has been able to tackle as a director with less than a decade of experience heading projects is by all means extraordinary.

While Natsume is still best known for the action blockbuster that was One-Punch Man’s first season, he never allowed that to pigeonhole him. He would reappear every year or two to jump from the pleasantly understated political thriller ACCA: 13 to attempting to tackle the off-kilter, atmospheric action of Boogiepop and Others. We’ve seen him coordinate the production of a wildly imaginative anthology series in Space Dandy, which he directed alongside Shinichiro Watanabe, a mentor he still turns to nowadays when it comes to musical choices. Although people tend to forget that, the first project Natsume led was actually the first OVA for Hori-san to Miyamura-kun, an indie effort that presented an austere world of two; a fascinating contrast with the lavishly presented ensemble cast narrative of Horimiya’s eventual TV series. Next year, Natsume will face yet another new challenge by succeeding a critically acclaimed director. By directing a Tatami Galaxy sequel, he’ll be returning to the series that featured his first televised episode as director and storyboarder, having taken over arguably his number one mentor in Masaaki Yuasa. It’s one interesting development after the other when it comes to Natsume.

Even in this tightly packed, fascinating career, a single project stands out from the rest; the exceptional within the exceptional, something he deemed a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. When it comes to titles pitched by a producer to a creator—which is to say most of them—the former will tend to have a precise goal in mind. It could be a specific title to adapt, one current trend they want to ride, a type of narrative they think could be a hit, or if they’re feeling terribly generous towards the arts, perhaps one idea that they genuinely believe would be interesting if handled by that team. That is the norm, but Sonny Boy is anything but normal, hence why its backstory is quite different.

Veteran producer Motoki Mukaichi met Natsume for the first time during the preambles of Space Dandy, and it wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that he fell for him at first sight. He had made a name for himself at Bandai Visual, which he leveraged into a position as chief producer and manager at Shochiku after he transferred companies in 2017; which is to say, the kind of job that allows you to get away with a passion project or two. And so, when their schedules aligned, he approached Natsume with a proposal to make… anything at all. While Mukaichi had some specific details in mind—you know who to thank for the constant cliffhangers, since he suggested having one twist per episode to keep viewers hooked—his pitch to Natsume could be summarized with anything goes, as long as you like it. Essentially a blank cheque, a gift that’s hard to come by in this industry.

Presented with that chance, Natsume did the obvious and took it. Now I don’t mean this to say that he accepted the project, which he evidently did, but rather that he maximized these unique circumstances that he might not be blessed with again. His diverse career had allowed us to see many sides to Natsume, even down to independent projects, but nothing can even compare to the way Sonny Boy lays him bare; his favorite artists and companions, his personal philosophical musings, all in service of depicting a singular worldview—his own. One of those trustworthy comrades noted that, while everyone had been able to tell how sharp of an artist Natsume was since his days as an animator, his constant presence as an unsheathed sword made this project terribly exciting for them. If you’ve found Sonny Boy to be fascinating, you should know that this has been the prevailing sentiment within its team as well.

When it comes down to it, the formation of that creative team might have marked Sonny Boy at its most self-indulgent. Natsume can rightfully justify the choice of Hisashi Eguchi as character designer by noting that his iconic style will feel nostalgic of bygone days to those who experienced them, but also very unique to younger viewers, making the style refreshing no matter which angle you approach it from. At the same time, it’s no secret that he picked Eguchi—and honored his works—because he happens to be an old idol of his, in the same way that the cherrypicked soundtrack features nothing but artists he loves and new favorites introduced by the aforementioned Watanabe. Natsume took it to heart that everything was good as long as he liked it, and in the process of doing that, he set the perfect foundations to illustrate his own headspace in an animation canvas.

And, before a single shot was animated, Natsume was already making strides toward that goal. Given the backstory we’ve gone through, no one should be surprised to hear that he’s credited as this show’s author. If you’re familiar with his career, though, you might be surprised to hear that it’s not just the concept behind the series that he came up with, but also the scripts for every single episode—all of this, coming from someone with no anime writing experience whatsoever.

In the same way that he liberally picked and chose favorite artists of his to build the team, Natsume brazenly borrowed concepts and settings from popular pieces of fiction—anything from Robinson Crusoe to Super Mario—that allow him to explore classic dilemmas that he clearly has many thoughts on. Sonny Boy is Natsume’s own take on Two Year’s Vacation and Drifting Classroom, which is to say a Lord of the Flies-esque affair where an entire school suddenly shifts into the void, granting supernatural abilities to a few dozen stranded students in the process. As you might imagine, Natsume frames the factions that arise as a microcosm of society to have broader conversations; he sees forms of order as naturally replicating, but still worthy of critique, hence why many episodes tackle authoritarianism, capital, exceptionalism, faith, religious scapegoating, and so on. It’s all in the friction between the rules we need to function, and the freedom we need to live.

The central narrative thread that follows protagonist Nagara from inaction to playing a role in that necessary struggle, bettering himself and others in the process, is as simple as coming of age stories come. As a challenge to modern fandom’s tendency to solve all media, though, Natsume has made everything that surrounds it delightfully obtuse. The dry writing makes the deadpan, absurdist humor all the much funnier, but it also obligates you to stay on your toes and pay attention. The themes it deals with are never simple, nor do they necessarily have clear-cut answers, so you shouldn’t expect that you’ll walk off an episode having cracked the code. Despite all that complexity, the character writing is on the thinner side, as all but a handful of characters are essentially mouthpieces for Natsume’s worldview. On paper, this might sound incongruous and not all that compelling. And to be fair, it might have been if the scripts were what we were presented with—though again, the team that already found them fascinating would beg to differ. Either way, Sonny Boy is a work of animation. And boy, is it ever a work of animation.

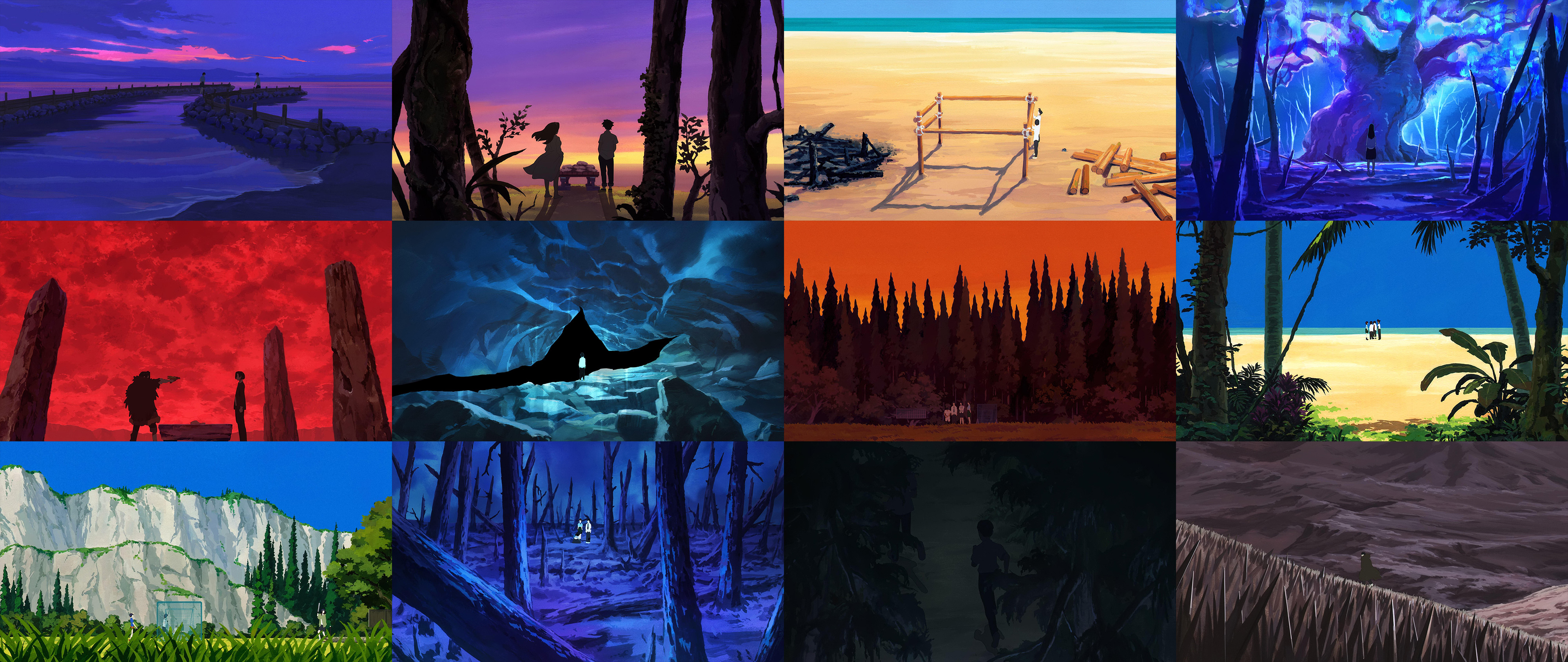

Throughout the process to bring all those ideas to life, Natsume remained thoroughly in control. For starters, he storyboarded half the show himself, which is a much more actively involved role than he’d ever had before. Although it’s not strictly an anthology series, many episodes take the cast to unique settings that embody the psyche of a student or a particular theme they want to explore, so it made sense for Natsume himself to be directly in charge of their depiction. While Sonny Boy’s ideas are wide-ranging and at some points could feel disparate, Natsume’s omnipresence acts as the perfect cohesive agent; never has an anime been about so many things, yet so organically held together as one.

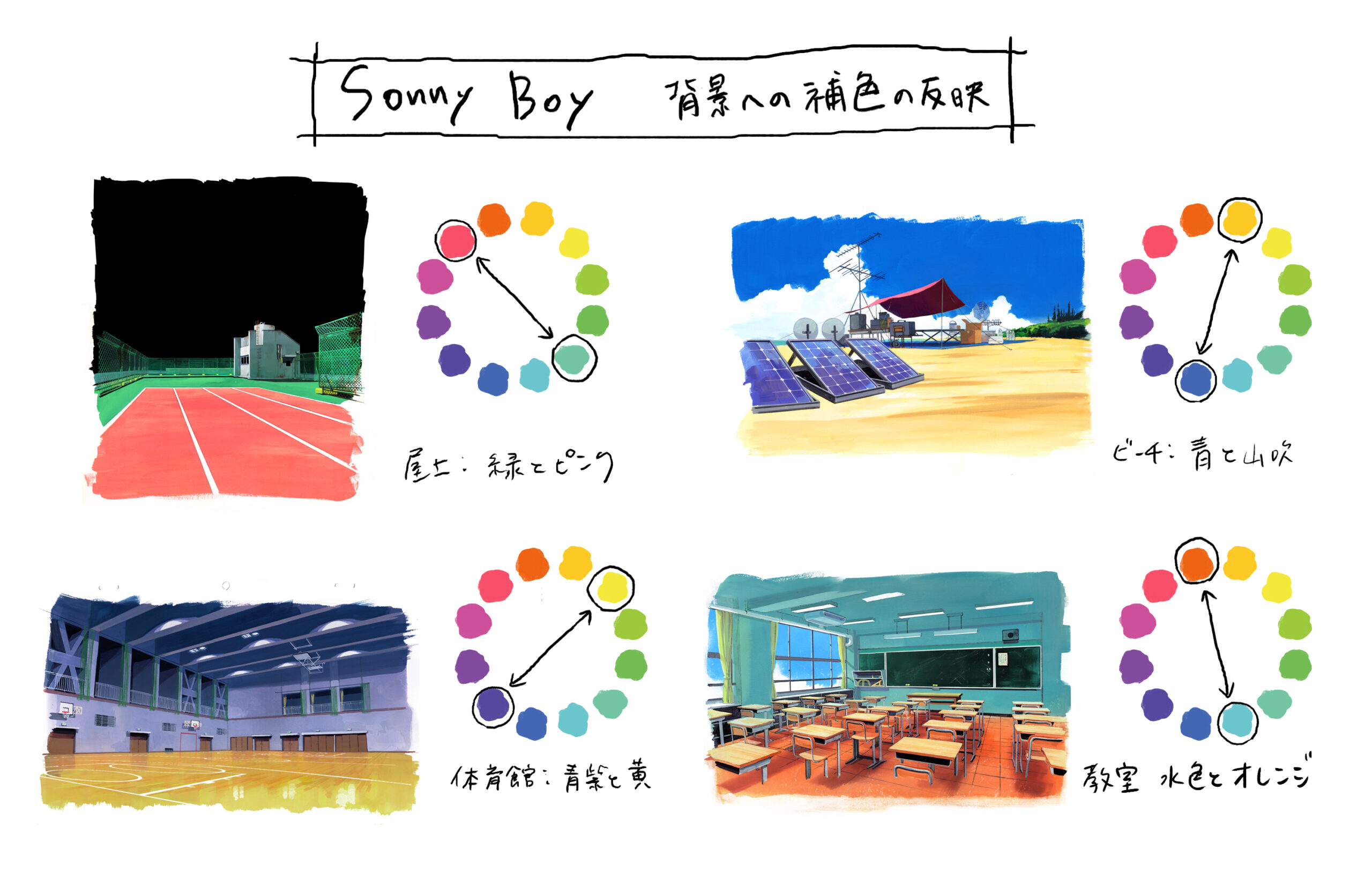

It’s precisely the depiction of those alien settings that I find most interesting, as Natsume took the idea of perfect cohesion so far that he demolished traditional walls between animation production departments. The art direction by Mari Fujino streamlines Studio Pablo’s qualities: without the intricate texture work they were known for when the studio’s name was synonymous with Kentaro Akiyama, we’re left with traditionally painted settings where the arresting colorwork defines the atmosphere.

Her team followed Natsume’s precise instructions, be it mimicking popular painters such as Henri Rousseau or making even bolder choices, such as depicting the abyss with pure RGB black; something you’re strongly advised against on TV, but that he felt necessary to depict both nothingness and infinite possibility. At the same time, the art team also went out of their way to interpret Natsume’s scenario on a more visceral level. As Fujino explained on the studio’s blog, Sonny Boy’s penchant for complementary colors is an attempt to match the uncertainty she thought exuded from Natsume’s writing—an interpretation he clearly found satisfying. By combining the director’s explicit requests with personal readings on his work that he admitted can get his own point even better than himself, Natsume’s world was completed.

That alone would have made Sonny Boy a beautiful series, but the finishing touch that makes it such a bewitching experience is that subversive spin I alluded to earlier. On this site, we’ve talked at length about SSSS.Gridman and Dynazenon’s triumph in building an engrossing world through director Amemiya’s full cel sensibilities; in short, an abundance of shots where essentially everything is handled by animators rather than splitting the workload with the art crew, eliminating incongruences and thus making it so that the audience is drawn into the world more effectively. So, what if you did the exact opposite—granting control to the art team, achieving cohesion on the opposite end of things?

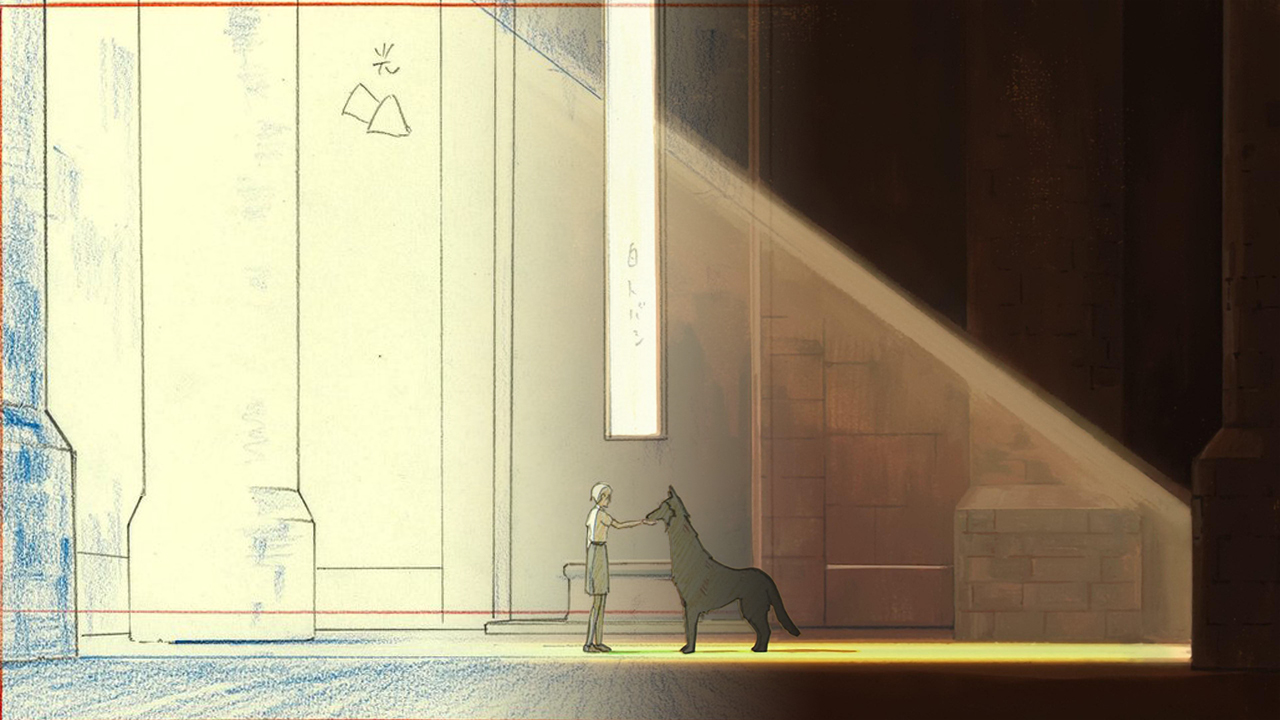

Now, that’s something that already exists as a common practice… sort of. You might have heard the term harmony: shots in anime with layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists. drawn by animators, but that rather than following the normal production pipeline that would eventually take them to standard digital painting, are sent instead to the art department to paint them. This technique was popularized by legendary director Osamu Dezaki through his postcard memories, which illustrated emotional beats in the most dramatic fashion possible. That practice has endured to this day, remaining particularly common at the end of episodes, be it with the sincerity that characterized Dezaki’s flourishes or as an amusing visual gag.

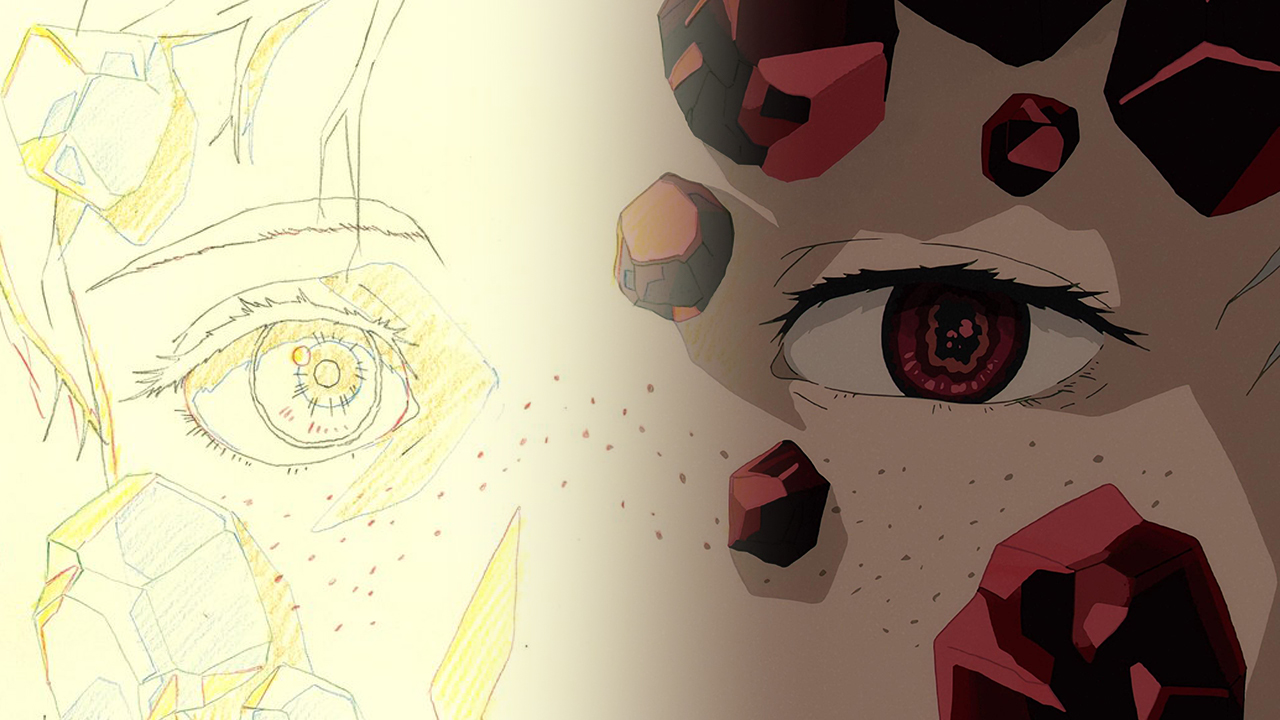

That is, however, neither the fitting tone nor the type of cohesion that Sonny Boy aimed for, so Natsume instead inundated the show with understated living paintings. While traditional harmonies tend to be dramatic closeups that highlight the expressions, Natsume reinforced the atmosphere of every episode with wide shots—as well as medium ones where he could afford to abbreviate facial expressions—that feel like scenic paintings come alive, which he achieved through a variety of techniques. Sometimes the character art was filtered once painted to mimic the simpler traditional texture of the backgrounds, there are instances where the coloring team painted over the lineart to achieve a similar stylized effect, and in some occasions, there were genuinely no animation assets despite characters and creatures moving on screen—the perfect opposite to full cel, zero cel. An approach that solidified that exceptional cohesive feel, while also making the exceptions stand out even more; when the cast ventures into a flat digital world, or when we’re presented with Rajdhani’s scientific inventions and their thick white outlines, they really do feel different from Natsume’s seamless norm.

Although that’s the aspect that stands out the most in this regard, for its prevalence and impact on the overall experience, the truth is that there are many more techniques at play to bring Natsume’s ideas together. A digital process by the name of cutout was applied to the traditionally painted backgrounds to deliberately damage smooth gradients and introduce some degree of banding, which happened to achieve a very similar effect to the digital noise that was often applied to the effects animation when supernatural abilities were at play. No two aspects are at odds in Natsume’s world—and when they are, you can tell it’s for a reason.

However, is it actually possible to create one cohesive whole based on a single person’s vision on such a scale, with the large teams that commercial animation requires? In the end, the truth is obviously not, but that couldn’t stop Sonny Boy from creating that perfect illusion. The piece that completed Natsume’s puzzle was the craftiness on a management level, something that’s always required for a project to live up to its potential. By giving absolute freedom to the author, allowing him to write every single script, and then have him control the execution to such a degree, Sonny Boy had built the perfect net to sustain itself—but nets have holes, which animation producer Yuichiro Fukushi is an expert in filling. Over the last decade and a half, Fukushi has built a very impressive list of acquaintances, as projects like OPM can attest to. Rather than aiming to amass sheer production muscle, though, he instead helped Natsume build a team featuring the creators that he’s most comfortable with, those who get him most deeply. In the end, even those close acquaintances have admitted to struggling to get Natsume’s full nuance, but their efforts clearly paid off.

Fukushi’s craftiness can shine even in the art of cutting corners, as shown by Sonny Boy’s outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio. practices. Madhouse titles often have to do with less than ideal subcontracting to Korean studio DR MOVIE simply to get things finished in time, as both Natsume and Fukushi themselves are perfectly aware of. When it comes to Sonny Boy, however, the subcontracted episodes have been arranged with fairly potent teams that they’re acquainted with, and with special arrangements on top of that to protect that cohesion. Episode #05 was fully subcontracted to studio WIT on paper, but its most important emotional beat—a moment of intimacy between the main two characters—was animated in-house, following Natsume’s script and storyboardStoryboard (絵コンテ, ekonte): The blueprints of animation. A series of usually simple drawings serving as anime's visual script, drawn on special sheets with fields for the animation cut number, notes for the staff and the matching lines of dialogue.. Episode #07 was sent to CloverWorks under fairly similar terms, but it’s #09 that serves as the best example: storyboarded by a very good friend of the team in Keisuke Kojima, and produced at his studio REVOROOT as payback for a beautiful favor, making it an outside team that might as well have been in-house. Fukushi the puppetmaster was perfectly prepared for this project.

The final aspect worth noting is the necessary balance in a team project. Much like the show advocates against totalitarianism, Natsume understands that there needs to be room for individual expression in a creative project—while still being aware that it can’t overpower his overall vision. This is why he was proud to talk about the decision not to have a chief animation directorChief Animation Director (総作画監督, Sou Sakuga Kantoku): Often an overall credit that tends to be in the hands of the character designer, though as of late messy projects with multiple Chief ADs have increased in number; moreso than the regular animation directors, their job is to ensure the characters look like they're supposed to. Consistency is their goal, which they will enforce as much as they want (and can)., granting each episode the possibility to iterate on the character art in their unique way… which wasn’t fully true in the end, as there was a chief supervisor of sorts. For those outsourced episodes further away from his own hand, Natsume deployed regular animation director Keita Nagasaka as a temporary chief supervisor, making sure they still fell in line with his overall vision. Again, it’s all about balance.

The greatest showcase of the potential held within that space of personal expression that Natsume maintained is the stunning episode #08: storyboarded, directed, and supervised by young star Keiichiro Saito, another reliable comrade of his. Saito had already directed episode #03, where he admitted he had to go against his instincts and hold back for the main attraction that was #08; which is to say, that for the first time he didn’t animate half the episode as he tends to when he acts as director, something he gladly did for his latter episode.

In an episode built from the ground to be different from the rest, as a perfectly self-contained emotional journey that contrasts with Sonny Boy’s general open-endedness, Saito and Natsume met in the middle, making an unusually good point for centrism. The former smoothed out some of his most notorious quirks like the low drawing count, openly embracing Natsume’s precepts for the series like those living scenic portraits, but ultimately making that framework his own to fit his personal interpretation of the series director’s writing. Natsume’s usual bright colors were replaced with the earthy palettes that Saito is fond of, it was his own selection of famous painters that the art team was made to use as reference, and the episode was imbued with a solemnity that Natsume’s drier, more matter of the fact delivery hadn’t been concerned with. Sonny Boy #08 is a story about love and subservience, one that I strongly recommend anyone to check out, even if they have no interest in the show. Though, as you can imagine, I would also advise people to give this unique series a spin in its entirety.

I’m well aware that Sonny Boy isn’t a show for everyone. In a way, it’s a show for no one other than its author, who has been allowed to be self-indulgent to a degree anime rarely ever sees. But, if you’re the type of viewer that can get immersed in someone’s nearly uncompromised worldview, I can’t imagine a more interesting work than Sonny Boy.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

>depicting the abyss with pure RGB black; something you’re strongly advised against on TV

Why is this?

He alluded to it in an interview, if I recall correctly noting that it’s essentially considered a broadcast incident if you keep it up for over 5 seconds, but that they went with it anyway. Since he didn’t specify, I’m not sure about the actual nuance (is it if you have it over the whole screen to avoid making viewers think their TV is broken?) or if it’s a technical restriction that escapes me. TV regulations are very wonky either way so it didn’t surprise me to hear about it.

It’s probably a federal regulation. You’re not allowed to broadcast dead air on radio either, I imagine it has to do with the fact that every broadcast signal is technically being paid for by the second and dead air more or less constitutes a large waste of signal. Something something violating the broadcasting license.

I would guess it’s more an aesthetic rule of thumb, something you also hear often in printing, graphic design or painting. The issue is that, in the real world, you never get full blacks or whites, they always have some colors mixed in that you don’t notice too much, except if you compare them directly. If you use full black or white, it comes off as unnatural or harsh, which was the desired effect here.

Well done sir, clarifies so many things about the nature of the appeal of the show. Sonny Boy looked like a dream to me from the very beginning, nothing like an ordinary show. Thank you for providing the information of such a high quality!

awesome very nice

Is natsume being hideaki anno lol nice article as always tho

Hi kvin, Thanks so much for this article. Sonny Boy is one of those rare occurrences, a shot of anime heroin that revives the initial highs that initially brought me into the medium. The feeling of discovering something that was made perfectly for you in this moment. I am wondering: what is the best way to put money in the hands of anyone working on the show? Do they have PayPal’s or patterns? Is buying the Blu-ray’s when they come out actually helpful? If I’m unable to give any of these people money directly, how best can I vote with… Read more »

This one’s tricky! The most direct way of supporting the specific creators would be hunting them down and seeing if they have direct means of support, which isn’t feasible because not all of them do, or even really desirable because it shouldn’t be on viewers to put food on the table of an entire massive team. So really, it’s got to be a choice of whether you want to go through a system we know for a fact is broken and buy the show/related major releases. Will this financially support the creators? Sorta. Madhouse *is* in the committee so the… Read more »

Hi kViN,

Thanks so much for this thorough response. I dream of a day where I can update my episode count on MAL, and alongside the episode discussion prompt get prompted to donate to some sort of collective fund that keeps track of everyone credited on a given show, and pays out those teams directly.

Wistful idealism aside, I agree that we need larger changes much further up the food chain…

What a wonderful write up. Btw, did you notice one thing about that girl with power of monologue? Natsume said in an interview that there would be no internal character monologues, but he willfully broke his word starting an episode with internal monologues to introduce a character whose power was monologue itself. Fascinating.

Yep! I loved the subversion since there are multiple layers to it, because in the end of the episode you realize that the layer of fictionalization to her power meant that even she couldn’t really tell what everyone was feeling in a raw way. He warned that he’d do something like that in an interview and I found the result fascinating, as most things in the show.

Is this similar to how cartoons in the 40s like Tom and Jerry and Loony Tunes/Merrie Melodies had backgrounds that looked like paintings and then in the 50s switched to a simpler illustrative style of painting.

hello, I am an audience from china, it is a wonderful article. I like it, but I have a question about the term you used in your article. What is “registers” mean when you said that “but the range of registers and formats that he has been able to tackle”. My English is not good enough to understand this term. I look forward to your reply, thanks!

Hi! In this context, you can think of it as a broad genre/style. A comedic register, for example, can encompass very different styles (slapstick physical comedy, absurd comedy, even something like manzai) but at the end of the day that still falls into the same larger group. And Natsume is a director who has shown he can adapt to many of those.

Thanks for your answer! It’s really helpful. And I think it’s an interesting expression. I also have a question about your discussion on the forms of order. You mentioned that “he sees forms of order as naturally replicating”, so what is naturally replicating here means. I can easily see that Natsume is offering political metaphor in some episodes, but I wonder what is his unified opinion on the nature of social order. It’s hard to grasp that because the narrative in this serious is largely segmented, and different episodes deal with different topics, so I’d like to know how do… Read more »