The Meteoric Ascent of Megumi Ishitani, Toei Animation’s New Heir

Five years ago, we highlighted a woman who had yet to direct a single episode of anime as one of the most promising young creators in the entire industry. Today, she’s the mastermind behind the most celebrated moments of TV anime—this is Megumi Ishitani, who might genuinely be too good for her job.

We launched the Anime’s Future column here at the SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog to counterbalance the pessimism that becomes inescapable when covering this industry. Turning a blind eye to anime’s structural issues helps no one, but at a time when more people than ever were coming to terms with how deeply rooted those problems are, it felt important to note that there always are new sources of hope. Even as industry folks lament the alarming lack of qualified manpower, despite awful working conditions and creative limitations managing to drive away all sorts of talented folks, so many people fall in love with animation that powerful new voices still burst into the scene with regularity—whether they end up having a fruitful career or not.

To start that series with a bang, we chose to highlight two different artists in the first post. The first one was a precocious genius who works under the name China. Having demolished all sorts of youth milestones in the industry, his lack of experience in directorial duties at the time felt like no obstacle to foretelling an excellent career as a director, especially given his knack for capturing sensorial information of very specific moments even through illustrations alone. Time has proved those hunches right, as his appearances nowadays are synonymous with episode of the year caliber outings like Yama no Susume S3 #10, Heike Monogatari #03, and the music video for Mafumafu’s Sore wo Ai to Yobudake.

Alongside China was a more unassuming name. While he had already built a strong reputation among dedicated animation fans and of course within his generation of very talented freelance animators, not that many people were acquainted with Megumi Ishitani. At the time of writing about her, she had yet to direct one single episode of anime, having only done minor work for Toei Animation after graduating from university. For those who really paid attention, though, the potential was clear: those small contributions showed bursts of creativity and very appealing sensibilities—even when the subject matter was an anthropomorphized butt. And, perhaps more importantly, her student works already set her apart from the norm.

We’ve mentioned many times that Tokyo University of the Arts’ GEIDAI ANIMATION program is the most prestigious course in the country. Its reputation doesn’t ride only on the cache of the instructors and the technical skills they’re able to pass down, but on their emphasis on rearing artists with a worldview, voice, and message of their own. Their alumni more often than not become independent artists, as that mindset is opposed to the prevailing attitudes in commercial environments, especially ones that have grown to be as creatively asphyxiating as TV anime; when most resources are channeled into adaptations, and when the definition of those is narrowed down to exact recreations of the source material, art dies for the sake of products. Right now, the only somewhat stable hubs of Geidai folks are studio WIT’s Ibaraki branch, away from the main studio’s usual pressure, and the Pop Team Epic crew that might as well be as extraterrestrial as the name Space Neko Company suggests.

Ishitani defied those conventions by joining precisely the most corporate of anime studios; not that surprising of a choice given that the Toei Animation empire offers the type of job security that most anime studios can’t ever hope to, but seemingly at odds with the philosophy of the university she sailed from. And yet, it’s precisely the mentality nurtured at Geidai that allowed Ishitani to adapt to an environment like this. The goal she had set her eyes on was to create animation that everyone could enjoy, regardless of context or even their ability to parse it in full. She equated it to the experience of a child who can’t understand all the intricacies of a piece of fiction, and yet might fondly remember the impact it had on them years down the line. For an artist as inventive as her, with that intent to craft self-contained memorable experiences, having to work on weekly franchises wasn’t going to be enough to stifle her creativity.

That assumption was quickly put to test, in a very tricky scenario at that. Ishitani’s training as a director had run parallel to the production of Dragon Ball Super, a title that even the biggest fans of the franchise will acknowledge as an uneven ride. After acting as an assistant director for a couple years, where a couple of ending sequences were the greatest responsibilities she had, Ishitani finished her training stage during the last arc of the show. Her uncredited role as episode director and co-storyboarder on episode #107 was the first time she was somewhat in charge, but most importantly, series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario. Tatsuya Nagamine and co-series director Ryota Nakamura—the closest figure to a mentor she had at the time, who even supervised her unofficial debut—entrusted her with directing and storyboarding the finale all on her own. It goes without saying, but putting a newbie in charge of the climax for arguably the most important anime franchise of all time is both a ridiculous idea and the best thing they could have done. By that point, he’d already picked up on all the qualities we’d highlighted before, and his team’s bet paid off.

While #107 was already quite a strong episode despite the limited animation, #131 in particular raised the bar much higher than Super had ever reached before. Her storyboards were tremendously evocative for the show’s standards, and that adaptability she would need to survive in a foreign environment proved to be there already, as she threaded together a more satisfying action setpiece than most Dragon Ball veterans. Both episodes painted a clear picture of her still-developing style. For one, her tendency towards symmetrical compositions with subject centering, especially framed from the back; standard techniques on paper, but always executed in memorable fashion by her hand, with the added benefit of making deviations—throwing off that balance to signify power dynamics or convey unrest—feel all the more impactful. While at this stage she still had to polish up skillsets specific to commercial animation, her innate sense for shot composition alone already made her stand out in the eyes of many.

After brief stints in an unceremoniously axed project and doing design work for Precure, Ishitani moved on to her next major project: following Nagamine as he set sail for the Grand Line. Having salvaged Dragon Ball Super as best as humanly possible, and then proving that he hasn’t lost his touch with the very enjoyable Broly film, Nagamine was entrusted with revitalizing One Piece by taking over as a series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario. for the Wano arc. To say that he accomplished the goal would be an understatement not just of his leadership, but also the way the entire team bumped up the quality of their work tenfold, starting with the improved management. Nagamine’s Wano was a hit since its very beginning on episode #892, but they saved their secret weapon for over a year—more precisely, until episode #957, the first one in the series directed and storyboarded by Ishitani.

One Piece fans met a noticeably more refined Ishitani than Dragon Ball viewers had parted ways with. Her natural tendencies in storyboarding hadn’t—and haven’t—changed one bit, but her thoughtfulness was already on a different level, as was her technical ability to put it into more concrete terms. The episode made excellent use of shadows for one, enhancing her already eye-catching compositions but also regulating the delivery of information to the viewer, giving her excellent control of the tempo. Working alongside the best animators the studio has access to in a much healthier environment than that of Super maximized her intangibles, and she even found a way to synergize the content of the episode with her own animation ethos. Entrusted with a genuinely world-changing reveal, Ishitani put emphasis on the children as the news dropped; they’re confused about everyone’s extreme reactions over a political decision they’re not equipped to understand, some downright unaware of everything that’s going on, and yet the momentousness of the direction makes it feel like a day that they’ll remember when they grow up. Which is to say, a direct analogy for Ishitani’s animation goals.

By delivering an episode that memorable, Ishitani became a hero for a whole fanbase overnight. A fanbase that then had to wait for 6 whole months—meaning multiple cycles of the staff rotation—for her to show up again. And when she did, she reemerged with even more tricks in her bag, like her attempts to marry the sleek transitions she had been using before with multiplanar compositions similar to that of previous Toei superstar Rie Matsumoto, which give extra depth to shots in a very entertaining way. Ishitani’s creativity wasn’t in need of improving, but by piling up experience, she’s gradually becoming capable of pulling off ridiculous concepts like diegetic and tonally appropriate neon lights that turn a spilled drink into bloody intent.

The spectacular preceding scene, essentially a high-quality music video slotted into the episode, summed up both Ishitani’s self-contained greatness and the incompatibility between theatrical level ambition and TV anime, let alone a long-running title. One Piece is more stable TV show than ever, and Ishitani was granted more time than anyone else as well, but the friction between ambition and feasibility still caused her to struggle with the production of this episode. It’s no exaggeration to say that by this point, she had gotten too good for her job.

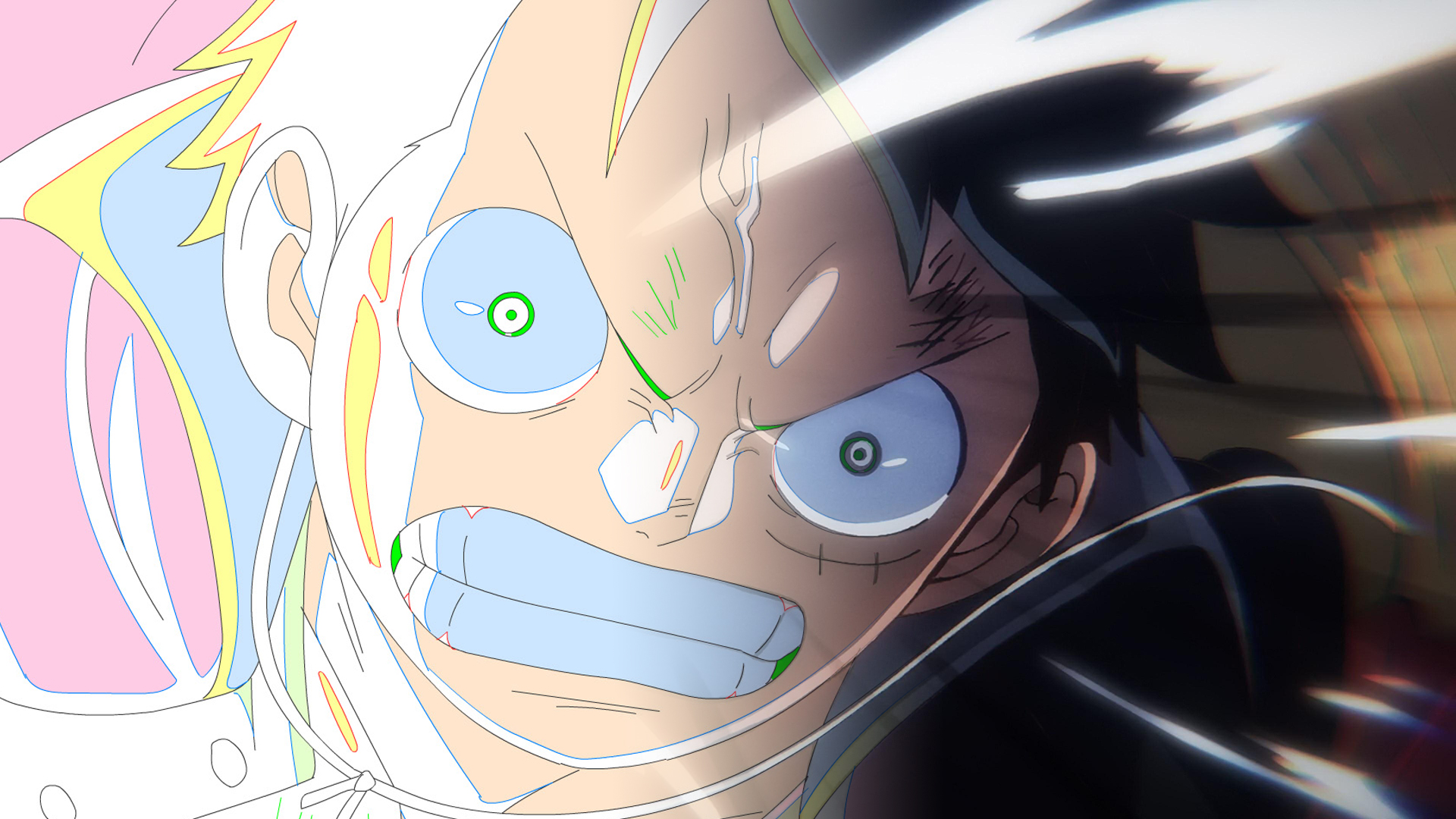

After an even longer wait, Ishitani’s latest work on episode #1015 shows no signs of dialing down the ambition. The episode represents perhaps the greatest technical leap between her works, with the compositing in particular being much more refined. For as ambitious as the lighting in her previous One Piece episodes was, details like the excessive depth of field coupled with chromatic aberration did more damage to shots than they helped. Fast-forward to her latest episode, though, and the eye-catching lighting is much more harmonious, nailing very complicated effects like translucency. Coupled with better guidance of the eye through techniques like racking focus, smoother transitions, and an uncanny ability to artfully stall for time, her technical skill is now at the level where it can live up to her inventiveness.

Though of course, it’s that creativity that drew others to her work in the first place. While her desire to make animation you can enjoy regardless of your grasp of the context and content can be misread as her not caring about a specific work like One Piece, nothing could be further from the truth. Episode #1015 is full of sequences that crystalize the spirit of the manga as well if not better than any other director’s; again, her execution is so memorable that they’re perfectly enjoyable with minimal context, but don’t take any of this to mean that she doesn’t engage with each specific work. Ishitani constantly emphasizes that animation is something that cannot succeed without a team on the same page, and when working on an adaptation, that mindset appears to include the author and their original work as well.

Out of the many highlights, Soty’s depiction of Yamato’s flashback with Ace might be the most elegant summary of Ishitani’s grasp on the material. On top of being a beautiful rendition of one of her favorite compositions, Yamato holding the Vivre Paper as Ace sails through a very narrow ravine is a poignant reminder of one’s freedom and the other’s lack of thereof, further emphasized by shifting the eye to the shackles. Ace’s parting words trigger a change in Yamato’s mentality, who rushes to bid him a more proper farewell; repeating the same composition with the hand holding the Vivre Paper, except this time Yamato is looking at an open sea, now actually capable of seeing freedom in the future. And then, a match cut to the paper burning, signifying the death of Yamato’s one friend. A rollercoaster of emotions in about a minute of footage, beautifully summing up the characters’ worldview with a scene that someone who only treated this as homework could never come up with.

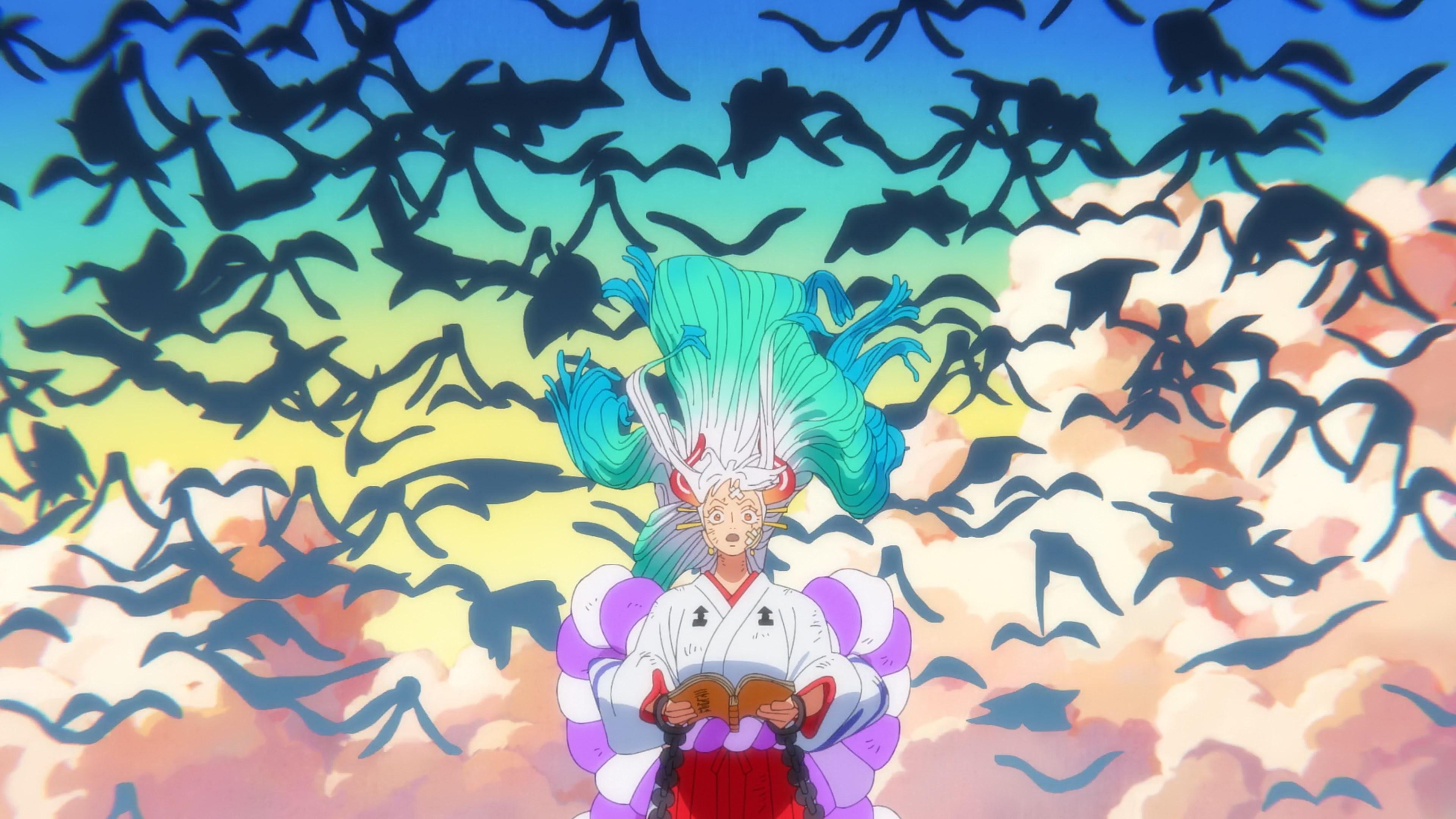

When it comes to embodying One Piece as a whole, and Ishitani’s own creativity as well, the most memorable scene is once again in Yamato and Ace’s memories; and once again in Soty’s animation, because he won’t rest unless he’s majorly responsible for Toei’s greatest episodes every single year. We’re transported to a world of pastel colors and looser forms, befitting Ace’s childhood recollections of the three brothers exposing their dreams. Suddenly, Yamato’s memories switch to another snippet of the past, with a warmer palette but similarly childlike style, featuring Gol D. Roger’s proclamation of his own dream. The two colors merge before exploding into birds: the ultimate embodiment of freedom, which to Roger and Luffy is the real meaning of being the king of pirates. For a character who craves nothing but that like Yamato, this is a life-changing event, and as a viewer who wishes for more bursts of creativity like this, Ishitani is game-changing as well.

As positive as this piece has been, I couldn’t bring myself to end it without telling One Piece fans to enjoy Ishitani for as long as they can, because each episode has made it clearer than the previous that she simply doesn’t belong here. This isn’t meant to be criticism of the series in any way, not even of the studio’s endlessly running commercial franchises. If anything, the role those have had in the careers of the most brilliant directors the studio has raised is something I find weirdly overlooked.

Save for exceptions like Kunihiko Ikuhara’s work on Sailor Moon and his disciple Takuya Igarashi with Doremi, there seems to be a tendency to underplay the past of their most critically acclaimed directors, which inevitably traces back to titles like these. The impersonal atmospheric style of Shigeyasu Yamauchi was perfected in works like Casshern Sins, but it’s hard to fully grasp if you’re not aware of his contributions to the likes of Dragon Ball and Saint Seiya. Rie Matsumoto is often treated like she materialized out of nowhere with Kyousougiga, but formally and thematically, her growth is all over Precure. Even Mamoru Hosoda, whose work in Digimon is still recognized, has most of his work at Toei swept under the rug—including his most personally significant works. Even if you don’t factor in their historical significance, these are all excellent works on their own, deserving of respect regardless of their context.

When it comes to Ishitani, the issue is not that she can’t make great anime in whichever franchise she’s deployed onto, but rather that she’s too ambitious for individual episodes of TV anime. While I wish that she eventually gets a major original work of her own—no doubt including dinosaurs—I feel like the most important change in her career would be switching to leading entire projects, preferably theatrical ones. Over the last decade, Toei has dropped the ball when it comes to securing alternative outlets for unique creators like her, which has been a contributing factor to multiple artists of Ishitani’s caliber resigning their crown faster than you’d normally expect. The ball is on Toei’s court now, because Ishitani has already proved that she’s the real deal.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

“Ishitani’s latest work on episode #1015 shows no signs of dialing up the ambition.”

I think you meant to say “dialing down” the ambition. I’m also very excited to see Ishitani get a bigger project to lead whether that’s a One Piece movie or an original TV show.

Oops, yeah I did! And honestly, as long as it fits how Big she thinks, anything works for me.

That chromatic aberration part you mentioned about episode #982, don’t you think the same can be said for some scenes in #1015 too? This artful stalling clip you linked for example, has some frames going overboard with the aberration just like the previous episode. I didn’t know they were damaging until you pointed it out though.

It’s still there to an extent, yeah. Everyone is going to have their personal tolerance when it comes to this (if it’s something that even bothers them at all), and myself I thought that this time around she got the team to simulate lenses in a way that achieved the goals (giving cinematic depth, directing the eye, simple coolness factor) without hurting the quality much. I have a friend who outright gets headaches with certain applications of chromatic aberration so it’s the kind of thing that I’m on the lookout for. And really, even when her episodes had rougher edges… Read more »

A bit out of context question since we are talking about chromatic aberration, how do you and your friend feel about the chromatic aberration in josee, tiger and fish? Most of the frames there used to focus on a small area, and the further you went from that focus, the bokeh/telephoto effect and chromatic aberration used to get stronger. It was there all the time and I really disliked this. Never understood why they did it that way. I guess chromatic aberration and bokeh are also a mentionable part of post effects in many kyoani anime? How do you feel… Read more »

It’s an artistic choice to embrace and, hopefully in a graceful manner, exaggerate the imperfections of real lenses. Josee is linked to its live-action predecessor and directly draws from Yamada works like Koe and Liz, so it’s not surprising at all that they made this choice. Personally I think that it might have been too ambitiously applied for a team that isn’t used to requiring this level of finesse throughout, but it looked nice enough for the most part. As for its usage in KyoAni works – it’ll likely be reduced in the future since its biggest proponent has left,… Read more »

I haven’t watched it’s live-action counterpart, does it have lens setting like this too that the anime tries to replicate? And yeah I know its direction is very yamada inspired, specially all those camera angles, leg shots and height of camera during lateral tracking. I always felt like josee’s team aimed for a kyoani vibe with the aberration and bokeh, but while kyoani uses those analog-feeling effects selectively on some sequences to capture special moments, josee just did it on ALL frames, which I found unnecessary. I show people this eupho kumiko vs josee kumiko example. The difference between what… Read more »

The comparison between the Josee and Eupho shots is actually really apt because it shows that for it to work perfectly, it’s not just the compositing you have to worry about but also the *composition.* The “awareness of the camera” that industry folks praise so much of Yamada doesn’t just mean that she has a good eye for those effects and succeeds at guiding the photography team, but that she has grown to storyboard things with it in mind already. That Eupho shot is nothing revolutionary, but the shot is arranged in a very readable way, with a layout that… Read more »

Thanks a lot for the elaboration. Your mentioning warpsharp now makes me think if josee’s line-art is another example of filters being abused or going wrong. Warpsharp filtering looks terrible especially when you are upscaling frames, making the whole image look as if it’s been squashed with water. The line-art becomes thicker, squiggly and more noticeable. A very similar problem can also be seen in a lot of bluray releases of old anime that had been remastered from dvd’s. And hell, no one can forget about Q-TEC upscales. (I can think of haibane renmei and chobits bluray on top of… Read more »

Hope she ends up getting to do larger projects (that hopefully involve lots of dinosaurs). Either way, its cool to see big longrunning anime episodes that are mainly focused on character acting. Soty is so great.

So Rie Matsumoto has its origin in Toei…

I joked that Ishitani & Soty were the new Matsumoto & Yuki hayashi, who would have thought they came from the same place.

It was a recurring joke to ask for Kyousougiga The New Generation featuring Haruka Kamatani and Kodai Watanabe, since both of them were the direct successors of the original duo. With him leaving to have more freedom (even if he has guest appearances for his friends) and her career never blowing up despite working on stuff as good as the new Doremi movie, I guess it’d be on these new prodigies to succeed them!

I just cant get over the lighting in the luffy roger scene. The use of dawn lighting and dusk lighting playing into the theme on top of everything else is just such a thoughtful creative touch and could not have been done with more crisply.

Wow, I couldn’t agree more. Her talent is the kind that demands an entire project