Spy x Family And The Messy History, Dynamics, And Intent Of Anime Co-productions

It’s no secret that Spy x Family is a co-production between Studio WIT and CloverWorks, but what’s the backstory behind that deal, what does it involve, and what are the dynamics, history, and intent of anime co-productions in the first place?

Spy x Family’s backstory

A recent interview in Nikkei Entertainment confirmed that Spy x Family’s anime project started with a pitch by distributing behemoth TOHO to Studio WIT. Although public confirmations are always valuable, this much was already guessed before the show even started. The production may be credited to two different studios that have comparably big roles, but the conceptual stages lean toward creators with known ties to WIT, if not directly employed by them. The most relevant example is of course director and series composer Kazuhiro Furuhashi, appointed by WIT producer and company board member Tetsuya Nakatake, who held Furuhashi in high regard as they’d worked together many times; most notably, in their producer-director tag teams for Le Chevalier D’Eon and Real Drive during the mid to late 00s. The biggest distributor in town suggesting the project to a regular hit-maker studio is about as unsurprising as their decision to entrust it to their close comrades.

What appears to be less common, at least if you aren’t well-versed in anime production dynamics, is the decision taken after that: to tackle the project alongside studio CloverWorks. Again, the main reason is something that was already guessed beforehand due to the friendship between specific producers, but Nakatake went into more detail by explaining that the genesis of the project was the Anime Studio Meeting events. For a brief period of time, AniSta gathered producers from different studios to share their insights and goals with each other. Nakatake was a regular guest alongside an old pal in Yuichi Fukushima, Aniplex’s star animation producer who is now acting as the de facto leader of CloverWorks. The two of them began considering the possibility of working together in a major way around 2018-2019, with the encouragement of WIT’s president as well. A few years later, the right circumstances finally manifested, hence why the idea of a co-production was pitched to Fukushima. An unsurprising but nonetheless interesting backstory.

This begs the question: what are those circumstances, and while we’re at it, what has that co-production entailed? Both studio producers have explained that their goal with this deal was achieving production stability in the long run, all but confirming that Spy x Family will have multiple seasons by saying that they’ve envisioned it as a long-time commitment. Nakatake even added that a major reason why he chose Furuhashi as a director was that he trusts his ability to continue delivering high-quality storyboards in time, so rather than a flashy burst of animation energy that quickly dissipates, they’re aiming for a consistently solid package with deliberately placed highlights.

As valid as that approach is, those official statements have a clear marketing intent, so you have to read between the lines and pay attention to the state of both studios to realize what’s actually going on. The truth is that neither studio, and especially none of their selected teams for this project, would be in the right situation to handle this series alone. WIT’s crew, gathered around Nakatake and animation producers Kazue Hayashi and Kazuki Yamanaka, happens to be comprised of folks coming right off Tetsuro Araki’s Bubble; this is patently obvious from its main animators like Keisuke Okura, and involves roles are critical as Furuhashi’s assistant series directors Takashi Katagiri and Norihito Takahashi. While Bubble had been finished ahead of its release a few weeks ago, we’re still talking about a team that had little to no break at all between major projects. If they’d had to tackle Spy x Family alone following TOHO’s original pitch, the project—the quality of the animation, the livelihood of their staff, or both—would have crumbled with time. While a co-production isn’t a magical solution to cut-throat scheduling, halving the workload is certainly a way to make it more bearable.

It’s worth noting that the CloverWorks crew wasn’t in a comfortable situation either. Although the studio’s animation producer on this project is the relatively inexperienced Taito Itou (Norimono Man, Horimiya), the core team is very much gathered around the aforementioned Fukushima, who only just wrapped up his previous show in Akebi’s Sailor Uniform. Again, this includes people he personally appointed like character designer Kazuaki Shimada—an acquaintance from The Promised Neverland—as well as others who have had no time to spare since Akebi, like the last assistant series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario. Takahiro Harada. As much as Fukushima’s magnetism can attract renowned creators, like beloved director Tatsuyuki Nagai and the popular leader of team imas Atsushi Nishigori, we’re talking about two studios that would be in for a nightmare if they had to tackle this project by themselves. The producers aren’t lying when they talk about their personal relationship leading to this cooperation, nor are they misleading people by saying their goal is long-term production stability, but you should still keep in mind that there are clear reasons why this partnership happened specifically in this project.

The dynamics of anime co-production

Now that you know how Spy x Family ended up in this situation, it’s a good time to find out exactly what does co-producing anime imply. While there are as many co-production models as there are co-production projects, Spy x Family is a good starting point due to its fairly even distribution. As previously mentioned, the most fundamental roles like direction and writing lean slightly towards WIT as they’re the studio that the project was pitched to, but both the groundwork and execution have the two studios represented in essentially all aspects.

In practice, this means that there are multiple duos leading specific departments. Spy x Family has two art directors in Kazuo Nagai and Hisayo Usui—the former appointed by WIT, the second belonging to CloverWork’s in-house team—as well as two chief animation directors in CloverWorks’s Shimada and WIT’s Kyoji Asano, for a couple of very representative examples. Even in roles where one studio has the leading voice, the execution is spread reasonably well between the two. MADBOX’s Akane Fushihara was appointed by WIT as the show’s director of photographyPhotography (撮影, Satsuei): The marriage of elements produced by different departments into a finished picture, involving filtering to make it more harmonious. A name inherited from the past, when cameras were actually used during this process. with CloverWorks’ Yuuya Sakuma as her assistant. While the former studio understandably provides a supervisor to oversee the execution of every episode, it’s the latter that is providing more sheer compositing personnel to every episode. In the end, things balance out in a fair way.

When it comes to producing each episode—which in this context means providing the directors and animators—the effort continues to be evenly spread out, following an alternating model. Each episode thus far has been split cleanly between the two studios when it comes to those roles, with WIT producing the odd-numbered episodes while CloverWorks handles the even-numbered ones. This will continue moving forward, perhaps with the exception of some climactic episodes, and with the asterisk that this specific order may shift whenever the show hits a fully outsourced episode; if that were to just replace one of the main studios’ slots rather than act as a buffer for both, this otherwise orderly approach could be thrown off-balance a bit. While you can never take long-term stability for granted, especially when both studios arrived with no breathing room, Spy x Family is on paper a textbook example of anime co-production.

Of course, you shouldn’t take this to imply that all anime co-productions are reasonable arrangements, nor that splitting things in the middle is the only valid approach to cooperation. Co-produced projects are very situational, and studios might simply find themselves in a situation where assigning specific elements of the title to one of the studios makes the most sense. One such example that has been on the rise in recent times, though it’s not always labeled as such for reasons we’ll get into later, are collaborations between 2D and 3D animation studios. You’ll often find the former handling most standard scenes, while the latter will focus on a major element of that work that is naturally less taxing to portray with CGi such as mech, large creatures, dancing performances, and so on. A recent example of this would be Godzilla Singular Point, brought to life by two powerhouses in their own fields like studio BONES and Orange.

The truth is that, as long as the result is satisfactory and the impact on the staff isn’t undoubtedly negative, there’s no such thing as an inherently wrong co-production arrangement. Plenty of collaborations are imbalanced when it comes to spreading the workload and yet perfectly successful in their goals, at least on a mechanical level. If anything, being mindful of the current circumstances of each production company—who has the most available staff and at which departments, whose strengths are conceptual and whose are in execution, which rotation is more efficient, and so on—is much smarter than splitting piles of work in the middle like a disengaged King Solomon.

For the better or the worse, the most popular modern example would be Darling in the Franxx; on paper, it was a co-production between A-1/CloverWorks and Trigger, but in reality, both its conceptualization and execution leaned very strongly towards Aniplex’s subsidiaries, to the point that the latter studio essentially didn’t touch the entire second half of the show. And yet, as much of a thematic trainwreck as it ended up being, it maintained its respectable production quality till the end. Projects can be objectionable on multiple levels and still somewhat succeed in collaborative production management after all; Tatsunoko dumping nearly all the hands-on work for the Pretty series to its co-producing partner Korean studio DongWoo on the cheap is questionable morally and qualitatively, but they still achieve a stability for the staff that most TV anime projects will never have. Labor issues in commercial creative projects are complicated like that.

In fact, it’s even possible for co-production plans to go completely off track and still beautifully succeed. The existence of Sarazanmai was first alluded to in a studio MAPPA recruitment campaign that was looking for production assistants to work with director Kunihiko Ikuhara. Once the project materialized a couple years later, it did so as a co-production between them and Lapin Track, a small studio founded by acquaintances of the director. To the surprise of everyone, it was actually Lapin Track that produced every single episode and special sequence, with their staff handling the majority of the animation and even writing tasks, while for undisclosed reasons MAPPA did essentially nothing in the end—which did not prevent it from being a fascinating series with a solid schedule and consistent production values. While I’d rather not dwell on negativity too much, a co-production failure is more likely to happen when that workload is spread evenly without considering the circumstances. In MAPPA’s case, that would be their more recent collaboration with Madhouse on Takt op.Destiny, which had the studios alternate between ridiculously uneven levels of quality and incomparable approaches to the production process; it’s never great news when the number of supervisors alone tells you who was in charge.

Anime’s history of co-production

Viewers who have a decent grasp of the state of the anime industry but not necessarily of its historical background have been quick to chalk up cases like Spy x Family to overproduction; assuming that co-productions are a developing phenomenon in response to the unsustainable levels of output, which leave studios no other option than teaming up. Now, it’s obvious that there is a link between the two, and there has indeed been an uptick in co-productions in the same way that all creative roles are being split into increasingly smaller chunks to make the job manageable under hellish schedules.

Studios are simply more prone to embracing methods like this in the current environment, where even if one specific project isn’t short on resources and time, chances are that the studio is already booked with overlapping projects elsewhere anyway, so they’ll be happy to halve their workload. At best, this is a way to address the constant bottlenecks that make studios so inefficient, at worst, it’s fueling the already critical issues of overproduction.

That said, let’s quickly dispel that idea: no, co-productions are not a new phenomenon. Like all management schemes to get animation made in barely functional companies, it’s essentially as old as anime itself.

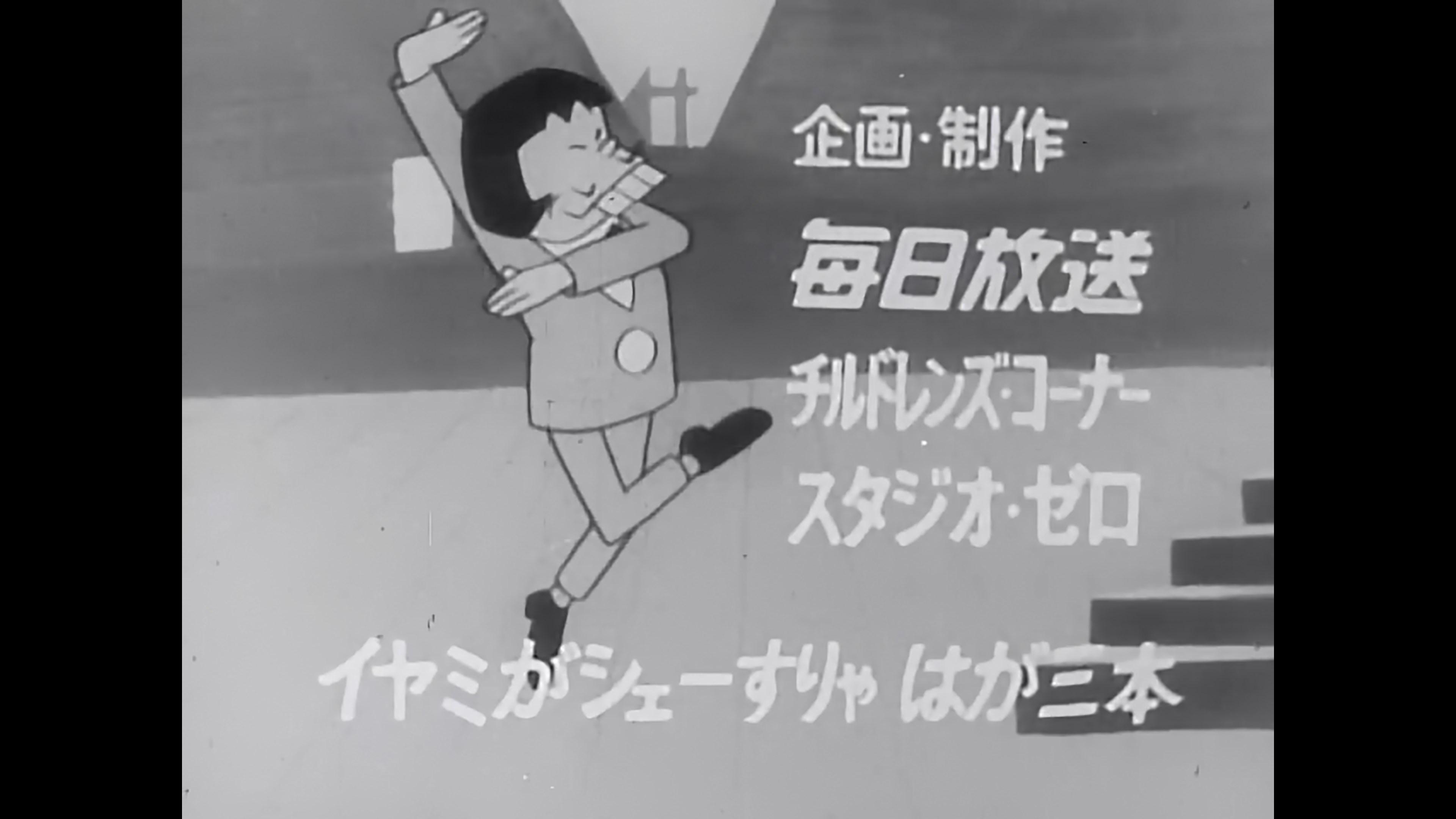

Back when we published an article explaining the mechanics and historical context of anime outsourcing, which you should likely read if you’re still not sure what producing anime entails, we explained that the very first TV anime series already had to rely on fully subcontracted episodes. Having noticed the growing exhaustion within the team behind Astro Boy, the legendary Osamu Tezuka made the executive decision to grant them a bit of a break by outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio. the entire production process for episode #34 to Studio Zero. That’s something he came to regret, as Studio Zero was actually a collective of mangaka who had neither experience with animation nor much of a desire to adhere to any internal nor overarching consistency for the series. This is very much representative of the industry in the 60s, with a tangible effect on how collaborations between studios happened as well; the standards for TV anime production had yet to be set, and multiple studios were formed as branches of preexisting media entities without much if any experienced personnel—and thus in need of help from other studios that had somewhat figured out the process.

After becoming the controversial protagonists for that first instance of full outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio., Studio Zero also happened to star in the first official co-production featuring two animation studios given equal billing. Given that Osomatsu-kun’s author Fujio Akatsuka was part of Studio Zero at the time, it’s no surprise that the studio was involved in its 1966 adaptation with Akatsuka himself as a supervisor. As they were by no means capable of handling its animation on their own, they relied on studio Children’s Corner, formed by ex-Toei Douga folks like Sanae Yamamoto. It appears that this time it was Studio Zero that didn’t take well to the other party’s unconventional quirks, so they reportedly tightened their grip on the production of the series over time as animators scrambled to get the job done thanks to the help of studios like Toei and Mushi Pro; “at the time, everyone worked for Mushi Pro during the day, then for Toei at night” recalled Osomatsu-kun chief director Makoto Nagasawa.

Those collaborations between teams that approached this new field of TV animation from completely different angles continued until the general concept of an anime studio was established; just a year after Osomatsu-kun, the same shortly-lived Children’s Corner would co-produce Kaminari Boy Pikkari-bee alongside a repurposed in-house team at TV station MBS, leading to all sorts of new and exciting headaches. Once TV production standards were more firmly established, co-productions quickly came to resemble what we see nowadays; less of an emergency mentorship process, more of a collaboration between companies that at least solidly belong to the same field. Although rarely credited with equal billing, A-Production represented that shift in their key role co-producing many of the greatest titles of the 70s alongside Tokyo Movie, the predecessor to the current TMS.

In retrospect, nothing exemplifies how widespread yet overlooked this practice is than the output of legendary studio Gainax during their golden age across the 90s and early 00s. There is no denying that they created some of the most memorable anime titles, that their staff were the project leaders and creative centerpieces, but people rarely consider that they made nothing on their own; not in the sense that they relied on freelancers and some major outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio., but rather that all their major titles were co-productions.

You might have heard that Evangelion was a co-production with Tatsunoko, and a look at the personnel alone would tell you that they switched to Production I.G for EoE—a partnership that also brought us FLCL. But less discussed is the fact that Karekano was made alongside J.C. Staff, that Abenobashi relied on Madhouse, that Nadia wouldn’t exist without Group TAC, and that they split shows with SHAFT with regularity. People aren’t wrong for associating all those titles with Gainax, but without fundamental assistance by those studios—on a management level but also by gathering the required personnel—all those iconic titles might not have been possible. Many unsung heroes have had a similar impact on people’s favorite anime, and what’s worse, those efforts aren’t always granted a co-production credit or even a series production assistance nod. It appears arbitrary, almost as if how much work you make isn’t what earns a studio a position of honor in the credits and press releases…

Actually, it’s all marketing

Or, to be more precise, marketing is a big part of it. The truth is that studio assignment was never a binary issue, and anime’s increasingly more tenuous in-house culture makes those lines even blurrier. In an industry where essentially everything outside of KyoAni has an argument to be called a co-production, the reasoning behind these decisions can end up being grounded on promotional potential more than production realities; especially now in the age of social media, studio names have become something to weaponize if possible, just another tool of promotion that can help a project catch the eye of viewers flooded with more entertainment than they can ever experience. A studio other than the primary contractor may work on every single episode, directly managing its execution, and then only be granted a series assistance credit that won’t be featured in any press release… or nothing at all. From production companies being publicly credited for a role that essentially amounts to acting as intermediaries to smaller studios that don’t have the leverage to demand proper acknowledgment, this is a messy situation that doesn’t always offer a clear answer.

If you want an example of how arbitrary and cynically motivated co-production branding can be, look no further than the aforementioned CG studio Orange. While they’re now a beloved studio with a dedicated fandom thanks to works like Land of the Lustrous and BEASTARS, the truth is that it took them a decade to earn their first animation co-production role. Was it because they suddenly stepped up in their assistance roles? While they did improve over time, the beginning of their first-page billing suspiciously coincides with the public acclaim for their work on a popular hit franchise like Code Geass—something that wasn’t all that different from their concurrent works, yet it immediately got them to start being featured as a main attraction in the otherwise 2D titles they participated on.

This very season we have a similar example in the output of Korean studio DR Movie. On paper, they’re co-producing one title this season. In reality, they have a reasonable claim to 3 of them, and that’s without counting more minor assistance work elsewhere. They’ve earned their position alongside Kinema Citrus for Shield Hero, as they’re participating in the production of every episode and have dedicated management of their own to oversee the process. But do you know which series that also applies to, albeit with a production effort more focused on in-betweening and painting? Kaguya-sama, whose every episode is essentially co-produced by DR Movie and yet has never dedicated them even a series assistance credit. Meanwhile, half the episodes of Paripi Koumei had their production outsourced to DR Movie—and the supposedly in-house ones were still mostly animated and finished by them, again to no major public credit. While DR Movie is as big as assistance-focused studios get, they’re not seen as a glamorous name, so work this significant goes overlooked on the regular.

In the end, the final lesson should be not to obsess too much with official branding; if the full animation credits aren’t necessarily representative of the reality of the creative process, you can imagine how misleading the PR-focused official summary of those can be. Commercial animation is necessarily a collaborative project, and in the dysfunctional state of the anime industry, it’s nearly impossible to find a project that didn’t require multiple studios to join hands and handle very significant chunks of work. For every Spy x Family where producers will happily highlight the names of the popular studios leading the production, many similar efforts involving less popular groups of creators are ignored. If you truly want to know who’s responsible for your favorite cartoons, there’s no other solution than to pay close attention to the full credit roll and especially what the majority of involved creators say beyond the usual public pleasantries. Or you could just follow sites like ours, I suppose that works too.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

Great article.

Learned a lot

Damn… That’s kind of sad. I didn’t know about DR Movie, and how good they were. Though, I kind of cynically figured that the announcement of collabs was to market a show, because there’s so many shows that outsource work with no credit. Probably what Takt op. Destiny was, to try to market the show. I knew many guys, including me, were checking the show purely because it was a MAPPA x madhouse Collab, but Kawagoe wasn’t on the level of Fukushi, hence the quality difference from MAPPA to madhouse.

But regardless, thanks for the article Kvin.

Which studio did better episodes ?

Generally speaking, that’d be Madhouse. MAPPA’s episodes are plagued with unintentional inconsistencies and overall look more stiff and limited due to the amount of animators and outside studios overseeing the animation direction as opposed to the 1-2 people of the Madhouse episodes..

DR Movie is such a weird studio in terms of the great stuff they’ve had a hand in without any real acknowledgment, even if you only limit to stuff they’ve done key animation on. And that’s not even limited to anime/Japanese productions… they did some of the best episodes on Avatar, for example…

And in recent years, they’ve pretty much helped save some anime productions from going completely down the crapper, like Re:Zero’s later seasons just by aiding in in-betweenning and paint. They’ve seem to have become the recently appointed Korean equivalent to a company like Nakamura Pro in how ubiquitous they’ve become in the industry’s outsourcing backbone. It’s sad that they seem to get the short end of the stick given their resume.

Really loves how this article zoom in on the individuals then zoom out on studio history.

Sure it makes me falls in the ”marketing around studio’s name” trap, that the article is critizising.

But it really helps me getting a global picture of the subject.

What do you think about any show by one studio where another studio is in charge of animation production assistance every episode as opposed to the co-production structure? Rent-A-Girlfriend for example is a TMS title yet Studio Comet was in charge of animation production assistance in virtually every episode?

It’s actually a co-production with Comet outright, even if they’re not credited on the same level. Which is to say, there are no episodes subcontracted to Comet, but rather that they’re counted as the main team to begin with. 7 episodes were fully outsourced regardless, which tells you how much management trickery it took to have a stable production that wrapped up ahead of time. As I said, there are no inherently wrong models, but the complexity of this net of studios speaks poorly of the industry altogether.

Wow, great explanation, Kevin …

It also answers what happened to takt op Destiny in Fall 2021. 👏👏👏👏

I wish more anime were produced with collaborations like this.

Not related to this article, but do you still plan to do a blog on Heaven’s feel 2 and 3?

I thought they lost some steam throughout so I wouldn’t have much positive to add to what I already said, as far as I’m concerned the first movie sums up the trilogy’s best qualities already.

One day the industry will crash and that will be the greatest day ever. Can’t wait

Nice article

DR movie literally animated all of the kaiji and handeled major chunks madhouse shows in 2000s that’s sad they didn’t get credited beside production assistance in specific episodes