Tomohiro Furukawa, Revue Starlight The Movie, And The Legacy Of Experience-Centric Anime

Tomohiro Furukawa draws from the philosophy and methods of living legends like Mamoru Oshii, Hideaki Anno, and his mentor Kunihiko Ikuhara. He reconstructs their teaching and his influences from countless fields into a unique thrilling style—that’s Revue Starlight The Movie, and what he calls experience-centric anime.

An indispensable skill for a director is the ability to tell their mom about the movie they saw the other day and make it sound interesting. Those are the amusing words of living legend Mamoru Oshii, and something of a mantra for Tomohiro Furukawa, who began realizing just how strongly they resonated with him once his career as a director took off.

After all, that one sentence encapsulates his entire approach to the creative process. For starters, it emphasizes the power of presentation, the aspect he rightly believes to be his greatest strength. Much like Oshii, Furukawa is a well-read movie geek with the most eclectic set of influences you could possibly imagine, all of which he will enthusiastically repackage into his works as well. Oshii’s words even hit close to home when it comes to the realization Furukawa had as a newbie director: it’s not just the audience you have to keep engaged, but also the team making it. In the end, the mom in the analogy is not just your audience, but also your crew, and to a degree, yourself. And thus, when the idea of a Revue Starlight follow-up was pitched to him, he quickly figured out the right angle to tackle the recap film Rondo Rondo Rondo and his spectacular Revue Starlight the Movie. That would be formulated into a line uttered by the characters as a lead-up to that final film, as well across its runtime: “we are already on stage”—a we that extends to everyone in front, within, and behind the screen.

Right now, Furukawa occupies a curious position. On the one hand, he’s being celebrated by industry icons and anime’s most reputable journalists as a disruptive director, so committed to his unique vision that he can bring avant-garde animation to an increasingly more restrictive commercial scene. On the other hand, he’s still unknown by the public at large as he has only helmed one project of his own, and being attached to a mass-produced entertainment factory like Bushiroad means that he’s not exposed to a likeminded arthouse audience but rather younger viewers who aren’t used to his nonstandard methods. And yet, I’m not sure I would hop onto a different timeline in the hopes that his career would pan out any differently. While he’s not aware of the extent of his delightful weirdness, as demonstrated by his casual explanations that drawing from 16th-century painters and niche movies that were never released in Japan is just normal, Furukawa does at least know that he offers something radically different than what his audience thinks they want—and he intends to exploit that mismatch to present them with new experiences.

For starters, it’s important to establish where such an unconventional director draws his influences from; not just because it’s important to understand his unconventional stylistic chops, but because it’s important for him, as a person. Fortunately, as an outspoken and knowledgeable industry figure, Furukawa has had the opportunity to share his inspirations in multiple outlets. He has touched on topics like the 70s to early 80s shoujo manga with BL elements that he’d borrow from his mother, which he felt weakened his perception of gender as a factor in romance, while also giving him a taste for beautiful nobility—two aspects you can still strongly feel in his current work. Even details like his thesis on the architectural history of the Canterbury Cathedral feel tangible in his output, as someone who has grown fond of using the setting design process as perhaps a more important storytelling device than the overt writing itself; especially after he noticed that the directors he looked up to didn’t feel the need to even draw a character to tell us about them.

Wide as his interests may be, it’s clear that he wouldn’t be making anime if it weren’t for those directors that he looks up to, hence why he has dedicated them so much praise. This goes from the likes of Shigeyasu Yamauchi, the first director to catch his attention with Saint Seiya: Legend of Crimson Youth, to Takuya Igarashi, whose efficiency and uncanny ability to craft a picture of his own while adhering to an existing work’s worldview fascinated Furukawa; so much so, that he tried to replicate the storyboardStoryboard (絵コンテ, ekonte): The blueprints of animation. A series of usually simple drawings serving as anime's visual script, drawn on special sheets with fields for the animation cut number, notes for the staff and the matching lines of dialogue. for Futari wa Pretty Cure #08 by obsessively rewatching it shot by shot.

If we’re talking about his greatest influences, though, there’s no doubt that we have to talk about directors like Hideaki Anno, whose very rhythm Furukawa still feels reverberates throughout his work, as well as the aforementioned Oshii—as close to a philosophical icon as he has in animation. It was from studying his works and collaborating with similar directors that he came to his interpretation of their mantra of information control: a concept intrinsically tied to the choice of material in expression to him, to the point that he has grown wary of purely thematic readings of the works of such idiosyncratic directors; why embrace that angle after all, when he has seen them morph their themes to conform to their means of expression? And when it comes to that process of choosing the perfect material to express what you have to say, or molding what you have to say to fit your preferred material, there is no one better than his mentor: Kunihiko Ikuhara. Had I just introduced Furukawa as a student of Ikuhara, though, his past self might have felt uncomfortable. And that complicated relationship is also palpable in his work.

There is no denying that Furukawa is Ikuhara’s apprentice. He has no desire to hide it and will shower his teacher with praise at any given opportunity, even as he pokes fun at how cute his insincere grumpiness can be. It’s clear that he has a deep understanding of Ikuhara in the way he alludes to curiously overlooked qualities of him—like his unmatched scouting abilities and willingness to surround himself with young creators worth listening to without compromising that unmistakable Ikuhara feel, which we’ve always highlighted in this site. Furukawa will often allude to him as his mentor with utmost respect rather than even saying his name, but if you’re an attentive fan, you might have noticed that he does this now. In his interview with Yuichiro Oguro for the 16th issue of AnimeStyle, Furukawa opened up about this topic more than usual. While he has always greatly admired him, and essentially modeled the way he puts together animation after Ikuhara’s management of resources and personnel, Furukawa hated the idea that people would neatly slot him as an Ikuhara follower and allow themselves to stop thinking any further; any nuance and personal qualities, lost to the ease of a label.

This really rubbed him the wrong way, not just as someone with a vast set of influences, but perhaps on a more philosophical level too. For someone who draws elements from countless works and fields, Furukawa has no interest in homages as direct recreations. Instead, he stores everything that catches his eye as bundles of information and techniques. The creative process is, at least to him, all about transforming, adding, and subtracting from those preexisting pieces to fit new scenarios—and the success condition, building something that feels entirely unique out of those atomized influences. Labeling him simply as one specific individual’s follower, then, is antithetical to his vision of the job. And the truth is that you can feel that friction in his work; when he was first entrusted with a project featuring theatrical girls who would fight each other, he quickly thought of giving them outfits similar to those of The Rose of Versailles… before quickly giving up on the idea, thinking that people would immediately made the Utena association and fall back on those Ikuhara follower preconceptions.

In the end, what made him change his mindset was precisely that project. It’s not as if Revue Starlight induced a revelation, but rather that the act of directing a show made him realize just how amazing and deeply influential Ikuhara really was. His mentor had given him a chance when he had no experience whatsoever in directorial roles and taught him the ropes practically, allowing him to be part of Mawaru Penguindrum’s young cluster of core directors. And by the time of Yurikuma Arashi, he already had him standing by his side as assistant series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario.. Leading his own project made it clear to Furukawa how much he owed his mentor, to the point of completely overshadowing that distaste for labels. At the same time, though, that admiration appears to be blinding him to the fact that inspiration works both ways. For as fundamental as Ikuhara was in Furukawa’s process to figure out his style, the latter has also been key in the refinement and evolution of his admired mentor.

In one of those amusing instances of Furukawa cracking a joke about his mentor’s grumpiness, he mentioned that one of the few aspects that he openly praised him for was his ear for euphony and his pun mastery. As usual, Ikuhara’s evaluation was right on the money. Thanks to works like Kaze Densetsu: Bukkomi no Taku, Furukawa had developed a taste for sentences and motifs with such a strong presence that they feel like they physically exist in the work, even when they’re not diegetically typeset into it. For a director who figured out that it’s all about the choice of material, this naturally extends to the delivery of those motifs through the graphic design and VFX, key elements in Furukawa’s work. From the memetic lines that the fanbase quickly latched onto—This is Tendou Maya, I am Reborn, the usage of Starlight as a verb—to Yuto Hama’s unmistakable imagery, his style is catchy in a way that even caught his mentor by surprise. This extends even to his upcoming work; while it doesn’t even have an official title yet, the aesthetically pleasant sounds of Love Cobra, the goofy puns, and Hama’s returning iconography managed to paint a memorable picture out of essentially nothing. Talk about oozing charisma.

Although iconography had always been a fairly important aspect to Ikuhara, it does feel like his praise of Furukawa’s eye—and ear—for these motifs came from a very genuine place, given how much he has come to emphasize this type of imagery and soundbites ever since they began working together. From Penguindrum’s Survival Strategy and Wataru Osakabe’s iconic graphic design to Sarazanmai’s ア symbols, this obsession has endured even when their respective schedules have kept them apart, so much so that these motifs might be the first thing that comes to mind when you think of Ikuhara’s modern output. Perhaps blinded by his reinforced admiration, though, Furukawa sees nothing but Ikuhara’s personality on the screen when he watches his works; and he may be right, but I do believe that he’s become an integral part of it by now.

Other than triggering that change of attitude towards his own creative lineage, though, how did Revue Starlight pan out? If you’ve been following this site, you’ll know that we found it to be a wildly entertaining series that couldn’t fully live up to its potential. Between the severe production struggles that they only endured thanks to key contributions by young individual animators overseas—a worrying way to be ahead of its time—and the uneven character arcs, it appeared to fall short of the masterpiece it could have been. Revue Starlight is a series about stage girls competing for the glory of the top spot in a setting equal parts Takarazuka and surreal fantasy. Its cast is neatly arranged in couples and trios with a shared theme, but those were not created equal, and the central pair with bigger shoes to fill happened to fall flat in the eyes of many; for a series that essentially amounts to a battle of charisma, it didn’t manage to properly sell the characters that finally stood on top, which leaves a bit of a bitter aftertaste even with its exciting finale.

Given Furukawa’s character, you’d think that he would quickly move onto entirely new projects, but the pitch to follow up Revue Starlight with a couple of films—an enhanced recap and a proper sequel—became a tempting idea to him. Bushiroad designed the franchise to be a wide multimedia property with actresses who play the characters in musicals as well as voice them in the anime, and it was by speaking with them that Furukawa grew increasingly conscious about the recurring theme of acting. They were playing a fictional character, those were playing a character in their play, and were they all not playing a character of themselves as well?

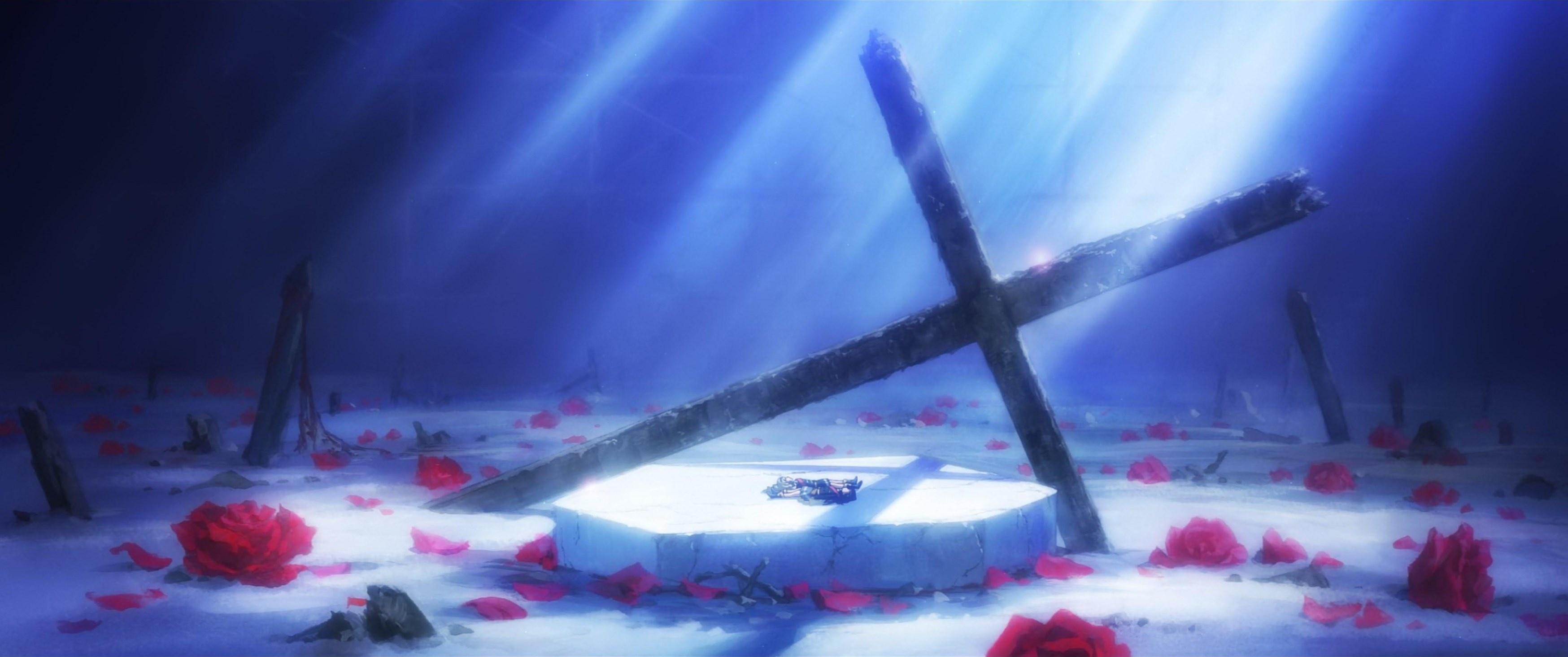

Speaking with Momoyo Koyama, the actress behind protagonist Karen Aijo, was a particularly illuminating experience for him. Koyama had opened up about her struggles to get into Karen’s shoes; how, as a somewhat pessimistic person, she struggled to become an impeccable bright protagonist. Karen is the very embodiment of a protagonist, but that friction between the flawed human nature of the actor and a role that feels so artificially perfect got him wondering—what if Karen was acting as well? That impulse got him to dig deeper into the character, unearthing her worries and even the hypocrisies that he concluded the original series with. And so we have Revue Starlight The Movie, the story about Karen’s death and rebirth: gone is the girl who simply wanted to star in one specific play alongside her friend, reborn into a true actress who yearns for the stage.

As we’ve been establishing, though, what Furukawa says is almost secondary to how he says it, so he had to figure out the right way to approach the production as well. The director has alluded to anime overproduction as one of the important factors here, arguing that if veteran directors and large studios already feel the pain of assembling a high-profile team that can put together consistently polished traditional animation, someone like him stands no chance. With that out of the picture, he decided to play to his strengths with what he called an experience-centric movie. Furukawa fondly looks up to his aforementioned idols, to their works of the 90s that left very strong impressions on you even if you couldn’t follow all the narrative beats. He made a fully conscious decision to go against the trend of emphasizing lore and wordy plotlines with a more viscerally rewarding movie. One that speaks to your senses more than to the database in your brain, a catharsis best felt when physically in a theater—it’s a show about being on stage after all.

This can be felt right off the bat. The very first sequence in the movie wasn’t actually in the script, but Furukawa felt the need to immediately catch the attention of the viewer with the most satisfying popping tomato ever felt in animation. Random as that may seem, tomatoes are arguably the most important motif across the whole movie, and for very Furukawa reasons at that. Revue Starlight had notoriously always featured a talkative giraffe as an avatar for the audience, and in digging deeper into the dynamics of the stage, Furukawa concluded that it’s not just the performers but also the viewers who willingly let themselves burn down and be consumed. To represent that idea in a fairly straightforward fashion, the script included a scene where the girls would eat the giraffe’s meat. Finding that scenario a tad too grotesque, Furukawa pulled from his endless list of influences and remembered painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo, who would often construct human portraits out of vegetables. Thus tomatoes became the heart of the audience and the film itself, and a scene that may have been somewhat eerie became a much more memorable nightmare. Oh Furukawa, never change.

All motifs in the movie follow a similar pattern. After all, this experience-centric approach is nothing but a practical application of the animation philosophy he had derived from his idols, exploiting his amalgamation of influences to fuel the constant spectacle. Revue Starlight The Movie is a thrilling ride that repurposes elements from everything between Lawrence of Arabia and Mad Max Fury Road, always following his formula of addition and subtraction to these pieces. The confrontation between Junna and Nana, for one, uses a setpiece from the 1985 film Mishima – A Life in our Chapters where a representation of the Kinkakuji opens up in half and blinds a character. As it turns out, blinding lights had always been a motif for Nana, representing the brilliance of the first stage she stood with her friends—one that she struggled to move on from, and that she could never grasp again. This gave him the excuse to use an inherently cool staging technique in a new way that fit his own scenario; and if it hadn’t, he might have just altered it to give himself a good excuse to do it anyway. After all, the memorable experience comes first.

Watching Revue Starlight The Movie is an assault on the senses in the best possible way, as the screen is flooded with Furukawa’s ideas and the bombastic audio accompanies them. While the writing feels more poignant thanks to the further consideration that the team gave to the dynamics of the stage, it’s not more words on paper that made so many people fall in love with the movie, but rather Furukawa’s unabashed commitment to his greatest strengths. The character dynamics that people already did love in the series were never built upon particularly complex writing, relying instead on the visual charisma, stage presence, and eye-catching direction that Furukawa granted them. This movie is a bold escalation of that by a director who admits he can’t tell a story in a straightforward way, but whose imagination and creative ammo could take you on an endless jaw-dropping ride; and that’s no exaggeration, given that even after leaving many ideas on his plate, Furukawa had nearly three hours worth of concepts planned for this movie’s eventual two hours of runtime.

It’s comforting to see this team succeed in making something that, despite being partly a consequence of the state of the industry, is as beautifully anachronistic as Furukawa imagined it to be. However, not everyone shares that feeling of success in the end, and that once again relates to the director’s philosophy. For as much as comrades in arms, viewers, and journalists alike praised Revue Starlight the Movie as a roaring success, Furukawa has repeatedly said in his eyes it’s kind of a regretful failure; maybe one that’s proudly disruptive in its goals, loud and catchy in execution, but ultimately dragged down by his alleged inability to live up to his vision and the potential of his team. The immaculate critical acclaim has only confused him, to the point that he’s trying to reverse engineer the qualities people see in his work from that critical appraisal, because he can’t see them himself.

For as much as I wish that Furukawa is ever able to make something that he deems a success, I’m afraid that even if he’s able to accomplish even more than he already has, his impressions will always be tinged with regret. If he was in this business to focus on feature-complete storytelling or polished animation, he might achieve something more tangible and convince himself that he did succeed. What he is chasing as an experience-centric filmmaker, though, is an idea. As an individual, his goal is to match the reverberations of his idols, those that caused him to pursue animation in the first place. And those, you can never grasp. Here’s to more fascinating alleged failures then, I suppose!

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

I loved it so much

From Japan, I read this review interestingly.

Good review!

such a great review. I learned a lot and agree entirely!