Nijiiro Hotaru: Rainbow Fireflies – Toei Animation’s Stunning Tribute To Their Past, And The Threats To Their Future

10 years ago, Toei Animation released Nijiiro Hotaru: Rainbow Fireflies, the stunning culmination of a lengthy production to honor the iconic works of their past and the power of traditional animation altogether. A decade later, the loss of projects like this threatens the studio’s future.

Toei is a conglomerate of entertainment that no anime studio can hope to compare to, and in some regards, that none of its peers should hope to be likened to; for as colossal as their legacy in anime is, that massive footprint also casts some pitch-black shadows, both in labor and creative fronts. Over the last 7 decades, their animation division has evolved into the behemoth it is right now. One that is capable of producing many concurrent, never-ending worldwide hits, and as One Piece viewers can attest to right now, also of doing a fantastic job with them when those titles are well-managed. As more veteran fans of the exact same series will remember, though, their model can also translate to continuously stressful work and a result that feels like it only exists out of inertia and the need to have a product delivered weekly.

While the anime industry depressingly marches towards a future where studios are little more than assembly lines, Toei is a seasoned veteran for whom that outcome is nothing new. They’ve been treated as such for many years, yet still manage to bundle enough creative nuggets within those commercial obligations to stop cynicism from fully taking over. It may be a precarious balance, but Toei has found a formula that allows them to comply with those demands while putting together memorable work and rearing some of the most brilliant young minds in anime. Repeating cycles with the likes of Sailor Moon, Doremi, Ashita no Nadja, and across Precure, with Kunihiko Ikuhara, Mamoru Hosoda, Takuya Igarashi, Rie Matsumoto, and Haruka Kamatani—these positive patterns are not a happy accident. You can never take them for granted in one specific series, but there is one thing that has been a certainty for decades: there will always be something very interesting happening within Toei’s massive halls.

The trick here, of course, is that Toei has escape valves for that pent-up, radical creativity. While it’s possible to approach those popular long-running titles that the studio is known for with more ambition and creativity than is the norm, and the studio’s culture does encourage daring directors to do so, there is only so much one can do to push the strict boundaries of a popular action anime or a huge franchise that must continue selling plastic. It’s often the most idiosyncratic directors who handle iconic episodes of Toei’s flagship titles, but if that were all that they could work on, their careers at the studio would be rather short. Even if it’s only every now and then, wildly unique artists need to be freed from their shackles, hence why Toei appeared to make it a point to always have alternatives on the side as they evolved towards this factory line reality. One such project, released 10 years ago, was the unforgettable Nijiiro Hotaru—Rainbow Fireflies.

Konosuke Uda’s name certainly isn’t as glamorous as contemporaries of his like Ikuhara or his role model Junichi Sato, who earned their spots in the canon of Toei’s greatest directors of all time. However, a lack of public or critical renown doesn’t make anyone’s career any less important. For one, no one else can boast of being One Piece’s very first series director… though one Goro Taniguchi can claim ownership of the series’ first kantoku role, as he directed the pilot that decades later has led to the upcoming One Piece Film Red. Uda’s best works across different genre spaces, such as Lovely Complex, Ginga e Kickoff, and MAJIN BONE are neither commercial megahits nor your prototypical critical darling, but they’re the type of work that people find themselves remembering fondly. As a director who found himself lost and without a drive early in his career, working under the aforementioned SatoJun—and all-time master in injecting fun into the formulaic scenarios you’re likely to encounter at Toei—greatly energized Uda, who has since then consistently succeeded at conveying that enjoyment to the audience.

Within that career of quietly significant feats and pleasant but not extraordinary works, there is one major exception. One that was brewing since 2007, when producer Atsutoshi Umezawa approached Uda to pitch him a movie inspired by a novel that he’d recently read. Umezawa, who had joined the studio in the Toei Doga era and has continued to make time for weird little projects even after his retirement, managed to put together a very tantalizing offer. And to do so, he first sold the idea to the higher-ups, convincing them that it was the right time to pay tribute to those historically significant Toei Doga movies of his youth with a spiritual successor fully financed by the studio.

Umezawa was then able to pass down this perhaps once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to a director like Uda: creative freedom as long as he made something worthy of the legacy of the studio, with a high-profile team and much time at his disposal. While after a long process—2 years for the animation, 3.5 for the production as a whole, and nearly 5 to get it released—the higher-ups eventually got fed up and demanded a finished product, that pressure wasn’t enough to compromise a movie that stands toe to toe with Toei’s greatest achievements in animation. In fact, very few anime can even compare to what this team achieved.

As Uda explained in AnimeStyle002, while the premise of the project may have been sugar-coated, the road they set on wasn’t necessarily sweet—or even a road at all, given how much they ran in circles during the pre-production process, as they figured out the identity of the work they were creating. Nijiiro Hotaru’s journey began with Uda and Takaaki Yamashita, whose participation was a recommendation by Kenkichi Matsushita from the managerial side. Given that the only mandate from above they initially had was to honor the history of Toei Doga, Yamashita’s participation fit the bill; he had also joined during the latter stages of that era of the studio, and eventually found himself mentoring the likes of Hosoda and Tatsuzou Nishita, eye-catching embodiments of the studio’s modern possibilities. If one had to celebrate the qualities of Toei’s past while exploiting the strengths of their present, Yamashita would be their man. That is, in an ideal world where time is not a finite resource.

By that point, Yamashita was already in high demand, both in TV shows and with a theatrical career—his sole focus nowadays—that was taking off as well. Nijiiro Hotaru was such a lengthy commitment that it overlapped with not one but two Hosoda films, let alone other projects that required his assistance. As it was clear since the start that he wouldn’t be able to dedicate his full attention to Nijiiro Hotaru, Uda requested help from a very special artist who ran in similar circles: Hisashi Mori, a Kanada-style action animator who swerved hard to ride Mitsuo Iso’s realist wave but never lost his sharpness and geometrical forms, doubling down on the bold lineart henceforth. The three of them would go on extensive location scouting trips, an abnormality for the studio at the time, drawing concept art to help themselves envision the movie’s ideal form. In a way, it felt more like a careful archaeological uncovering of its natural outcome, rather than a team rushing forward with preconceived ideas.

Again, that process wasn’t easy, and the team found themselves going back on their decisions more often than not. The first major change of plans was within that trio: while Mori originally tagged in to help the busy Yamashita, Uda loved his bold drafts so much that it was quickly decided he should be the character designer instead. That also helped them address some early misgiving they had with the identity of the project; given the request to follow Toei Doga tradition except in a more modern context, Uda and his team felt that they’d overlap too heavily with other distant heirs of that style, such as Ghibli’s works or the then concurrent production of Mai Mai Miracle. By building upon Mori’s uniquely thick linework instead, though, Nijiiro Hotaru immediately felt like a work of its own. The animation pipeline they eventually built reflected those new dynamics as well. Yamashita still lent his image composition expertise by drawing countless rough layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists. that expanded the storyboardStoryboard (絵コンテ, ekonte): The blueprints of animation. A series of usually simple drawings serving as anime's visual script, drawn on special sheets with fields for the animation cut number, notes for the staff and the matching lines of dialogue., which then would be passed on to Mori to adjust acting specificities, and finally onto specific key animators to follow the standard animation workflow.

That change was only the first of many to come, many of them motivated by the previous decision they’d taken. For one, opting to embrace Mori’s bold lines had turned out to create too oppressive of an atmosphere, as they bitterly realized when they were asked to animate a pilot film. Trying to lessen that visual impact by imitating the brown carbon paper effect seen in works like My Neighbor Totoro didn’t work out either, as that gave a sleek autumn-y feel to a movie that was meant to embody the summer top to bottom. The solution they settled on was to interrupt Mori’s black linework with deliberately placed color traced segments that allow the pictures to breathe.

This was accompanied by a change in the art direction as well, further enhancing that fresh feeling. Anime Kobo Basara’s Seiki Tamura, who had replaced Studio Pablo’s Kentaro Akiyama’s early supervision due to scheduling conflicts—talk about getting two of the greatest specialists of their era—was encouraged to selectively drop the detail, mirroring the mindful polarization of prior Toei-adjacent masters like Takamura Mukuo. Uda had encountered Mukuo’s work prior to his tragic passing during Sailor Moon and had been fascinated by his style; so sparse in spots that it made him wonder if those paintings were even finished, and yet so arresting when all pieces were eventually layered. This deliberate economy became another major pillar in balancing the visuals, maintaining a strong impression but not to the point of overloading the breezy atmosphere of the town they were meant to depict. Heavy and light, modern and old, animation and live-action, fantasy and mundanity, life and death, the fundamental contrasts at the core of the work slowly began unfolding.

At its core, Nijiiro Hotaru is about the beauty of ephemerality, themed around creatures like fireflies that can only shine so brightly because they do so for a short span of time. It’s the story of a child timeslipping into the past, and rather than obsess about the mechanics of time travel, its focus is on appreciating the moment with the full knowledge that it will eventually pass us by. Protagonist Yuuta is encouraged to enjoy this once-in-a-lifetime summer experience, and he learns to do so, despite the specter of separation from his new friends edging closer by the day. Their adventures are set in a village that is bound to be abandoned and flooded to build a dam—an outcome that Yuuta knows to be inevitable as that was its fate in his original timeline. As he comes to realize, many of his new acquaintances with whom he’s having the time of his life have personal circumstances that will lead to similarly inevitable fallouts. And that is what the visual style this team settled on is ultimately meant to embody: very impactful in some regards like Mori’s lineart, because these are memorable events to everyone involved after all, but also with a tint of fragility to them. Nothing is eternal.

What completes the movie thematically is its confidence in new generations, which turns what could have been a bit of a downer into a very uplifting tale. Having taken notice of similar events in real life and knowing of their complexity, Uda avoided taking a side in the matter of the dam through a definitive authorial voice; it’s clear that the adults living in the village feel a certain way, but they’re presented as more passive and accepting of the inevitable. That is not the case for the kids, who openly voice their disagreement in a movie that is committed to letting them speak for themselves, even if it’s ultimately not within their power to revert those circumstances. It’s them that the future belongs to, and their criticism of the decisions adults take that threaten their world is held with as much respect as their ability to bounce back. After using the phrase “even so, children still live in the present” as the tagline to promote the movie, the final scene adds “and head towards the future” after showing that they’ve all stood up and found new ways forward. Nijiiro Hotaru has aged like fine wine, and the aspect is now more encouraging than ever.

With those themes finalized—something that took its time, given that they kept adjusting the script while the animation process was already ongoing—what remained was making the final stylistic decisions and finally putting all those ideas into paper. Although they still had to change their plans somewhat in this phase, the process was more straightforward by this point. Uda had it clear since the start that if he was going to pay tribute to Toei Doga’s classic titles and believably immerse Yuuta and the viewer into a rural town in the 70s, the techniques they used should reflect that as well. He had to abandon the idea of using cel animation because it was no longer feasible for mechanical reasons, but found himself drawing a hard line when it came to modern digital techniques.

As a consequence, Nijiiro Hotaru uses no CGi whatsoever, despite prominently featuring elements like the fireflies themselves that are more easily portrayed with those tools. The movie’s animation being fully drawn on paper and supervised by their own specialized personnel was also a point of contention, an anomaly for the industry and Toei specifically; while their investors’ reports have been taking pride for years about how much of that workload is quickly handled overseas by their Toei Phils subsidiary, Uda knew many of those sequences were drawn on tablets, so he limited the in-betweening process to national companies that he knew worked exclusively on paper. Every element of the movie was meant to respect analog animation tradition as much as possible, even if that meant limiting the camerawork or going out of their way with costlier subcontracting.

The most interesting aspect in this regard was the compositing process, which he deliberately entrusted to a photographyPhotography (撮影, Satsuei): The marriage of elements produced by different departments into a finished picture, involving filtering to make it more harmonious. A name inherited from the past, when cameras were actually used during this process. director like Masao Oonuki who had been working in that role since the days of physical materials. Oonuki was asked to limit himself to practical-looking effects, and even to accentuate a physical distance between the character layers and the backgrounds, similar to the one you would have when you layered celluloids. Foregoing the immediate immersive effect of a filtered picture with involved lighting effects, Uda strengthened the immersion he actually cared about: dropping the viewer into that nostalgic world of traditional animation, which may not have the calculated cohesion of the best digital works, but allows you to feel the handcraftedness more strongly.

Those traditional ideas permeated the philosophy of the animation itself. The team went out of their way to record the children they’d cast to voice the characters doing all sorts of actions that they’d be doing in the film, citing the methods of certain Toei Doga works. And once they had that reference footage to enhance the authenticity, all individuals were encouraged to draw as they pleased; again, trying to bring back that nostalgic feeling from an era where consistency to the character sheets wasn’t valued in the way it is now. Mori’s animation directionAnimation Direction (作画監督, sakuga kantoku): The artists supervising the quality and consistency of the animation itself. They might correct cuts that deviate from the designs too much if they see it fit, but their job is mostly to ensure the motion is up to par while not looking too rough. Plenty of specialized Animation Direction roles exist – mecha, effects, creatures, all focused in one particular recurring element. was geared towards protecting the identity of the characters through their gestures more than any specific visual style, and thus the movie became an endless spectacle of character animation with plenty of room for personal interpretations.

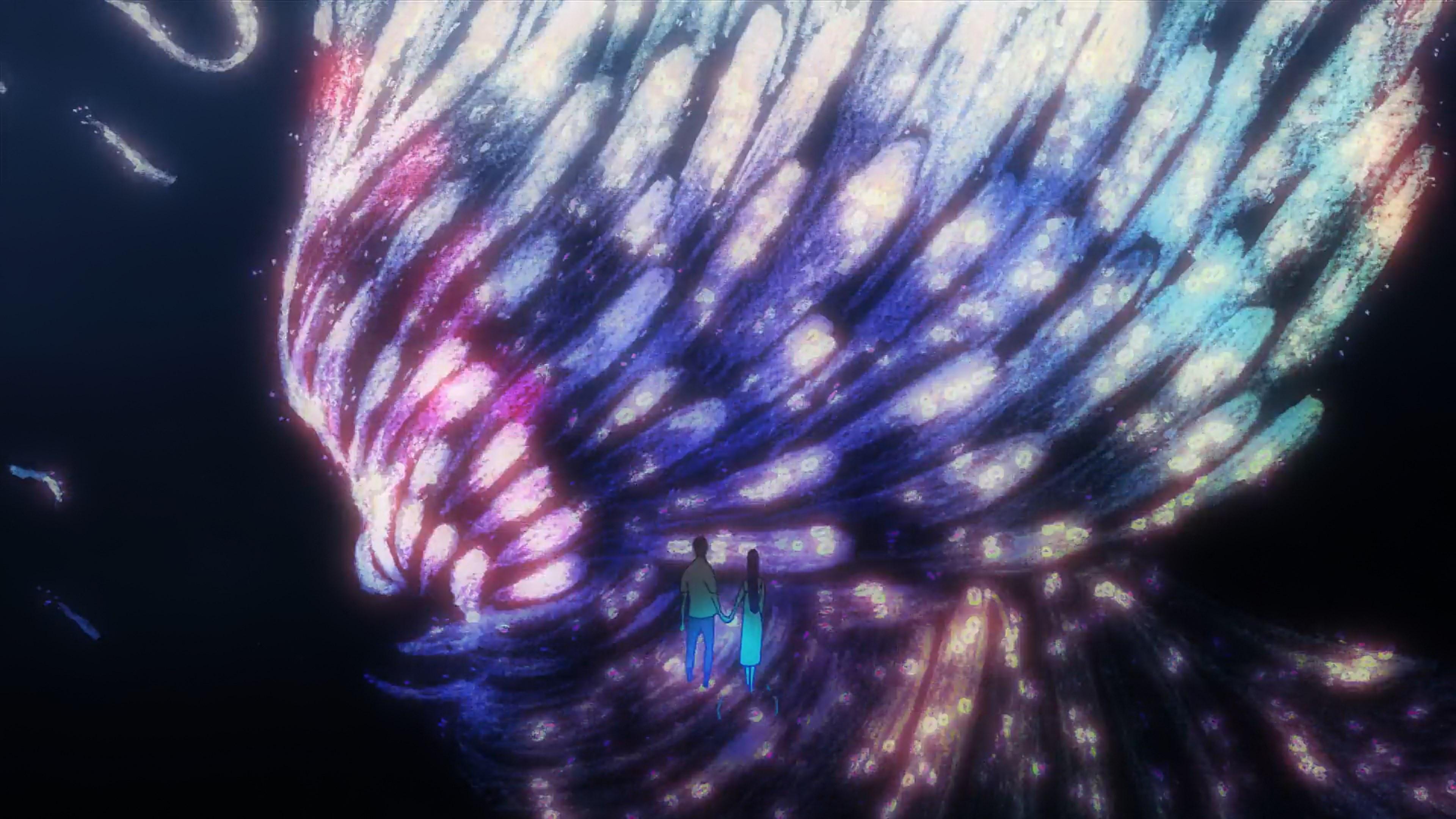

Be it Shinji Hashimoto’s expressive beady eyes and constantly flowing lines or Hiromi Ishigami’s softer touch, the movie wasn’t afraid of constantly shifting styles, yet it never felt like it damaged anyone’s characterization. No one embodied that approach better than Shinya Ohira, whose stunning work was deployed when most effective; his animation lives on the border between photorealism and surreal expressionism, which Uda knew would be most effective in the moments where the characters literally walk the path between life and death. While the movie would have perfectly justified in bolstering animator idiosyncrasy for the sake of it, especially in the context of paying homage to traditional animation methods, it’s worth noting that it was also mindful of whose unique styles to deploy where. Its team included the most skilled animators the studio had at their disposal as well as personal acquaintances gathered by Mori himself, making for a tight team where they were all aware of everyone’s best qualities.

The climax of the movie ended up being pure Ohira animation: all the drawings here are keys drawn by him, and it ultimately didn’t go through any sort of corrections because it would have been too time-consuming and hardly felt like a sequence where the idea of corrections even applies. The layouts for single cuts within it span around 6 meters long, and even the scanning process was tuned to pick up as much nuance from his drawings as possible.

The result of everyone’s work through a lengthy, very mindful production process is a movie that is nothing short of extraordinary. It wouldn’t be realistic to expect Toei’s output to be filled with works like Nijiiro Hotaru, and as Uda confessed, it was precisely that feeling that it was a special project that led to everyone giving it their best. He directly contrasted it with their franchise work, saying that everyone treasured the opportunity to work on a movie that stood on its own, with tremendous artistic freedom at that. Their enthusiastic reactions made it clear that, while you can’t expect Toei to pump out movies like this—something that would be antithetical to their spirit in the first place—your most brilliant creators need these escape valves.

For the longest time, Toei has had them, be it a vague idea to sell merch turned into the mesmerizing passion project that was Kyousougiga or Kenji Nakamura’s worldview colorfully plastered across the different titles he directed at the studio. Now, in 2022, I can’t say that Toei has projects like this anymore. And that’s already a problem.

Over the last few years, Toei’s alternative projects have been either greatly compromised or outright canceled. Popin Q was a quirky little film that was burdened with the responsibility of acting as an anniversary project for the studio when it was never planned to be, and after it underperformed, its promised sequel was slashed and eventually vanished into a book. The most interesting initiative since then was a project to give a platform to their young staff via short films, which after multiple press releases promising it to be a regular fixture, completely vanished after the first entry in the form of Megumi Ishitani’s Jurassic. Ever since then, the studio has focused on nothing but franchise work, while unique projects starve for internal support, are ceremoniously unplugged, or are scams we’re better off ignoring.

The dangers of this for the studio aren’t just theoretical. Some of the most popular figures at Toei have left in recent years citing precisely the desire to work on projects that don’t belong to larger, everlasting franchises; some have more or less left commercial animation as a consequence, while others have simply found themselves stuck in different franchises while their personal projects are stuck in limbo, because this is the type of industry we’re talking about. Uda, who to this day is happy to work with Toei sometimes despite having distanced himself from them, put it very clearly: you simply have to let your staff flex their creative muscles sometimes, in a way that franchise work will never let them. Nijiiro Hotaru was never going to start a new wave of analog animation, but at the very least it should stand as a stunning reminder that artists need freedom, even if their job doesn’t allow that to be the norm.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

Thank you so much for writing this. While I am not working in a creative field at all, I do recognize the need for more then just ‘conveyor belt’ work.

After multiple colleagues have left the last 2 years, it has become apparent to our leadership that only providing salary is not sufficient to retain motivated employees. At least they have acted accordingly upon these insights.