The Layout Crisis: The Collapse Of Anime’s Traditional Immersion, And The Attempts To Build It Anew

The layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists., the backbone of Japanese animation and its keen sense of immersion, are currently shattering. In this long dive, we contrasted the views of industry veterans and fresh faces with our own findings: the death of studio culture and training cycles, the pressure of cynical commercialism, the inherent labor issues, and the attempts to address it all.

In an era where anime remakes are announced anytime you blink, when greenlighting a reboot comes to producers as naturally as breathing, a modern take on a solid magical girl series like Tokyo Mew Mew doesn’t feel like it should provide much food for thought about the state of the industry. The passing of its artist Mia Ikumi earlier this year makes its timing truly unfortunate, but at the very least her work is being honored with a respectable adaptation of material that aged very well in the first place; beloved anime writer Reiko Yoshida penned the manga’s story 20 ages ago, building it around environmentalist themes that are now more relevant than ever—something that by itself already earns it a revisit.

Rather than bruteforce a comeback of the anime’s original staff, Tokyo Mew Mew New is being led by a capable team of creators who evoke its era and eye-catching artists who are tangentially related to the coolest moments in the 2002 show. With its calculated bursts of coolness and convincing recreation of early 00s comedic animation, Tokyo Mew Mew New is content to occupy a similar space to its predecessor: consistently entertaining, by no means extraordinary from an animation standpoint, but rather solid for its era.

As two respectable efforts set two decades apart, it’s easy to compare the differences in their production and see how those hint at the changes in anime altogether. Indeed, Tokyo Mew Mew New’s stock footage is often more dazzling than any burst of animation in the original, as anime has evolved in this flashy direction. Is there a price to pay for that, though? The answer is yes, with an arguably much larger gap in the quality of the layouts in each version. Despite the early 00s being a rocky period for anime in its own right due to the digital transition, and this series being far from the greatest example of immersive composition, this understated quality of the animation is simply worlds apart. As I pointed it out, multiple people reached out with a reasonable question: if this is as representative of a trend as I made out to be, why was it something that sounds as fundamental and in theory undemanding as the framing of a shot that took such a huge hit in quality? Shouldn’t the fancy animation be the victim of this alleged decay instead? To understand that, we have to catch up with the industry’s mentality, history, and practices that enabled that cohesive immersion in the first place.

We’ve mentioned before that inertia is one of the strongest forces in the anime industry. Practices and entire systems stick around for longer than they make sense, as things continue to be done a certain way simply because that’s the way you do things. All the major shifts in the production process have been spearheaded by specific individuals who historically appear to be about a decade ahead of their times, not so much because they’re that revolutionary, but rather due to the friction that widespread change is always met with. Even as their ideas are eventually embraced by the industry as a whole—usually for cynical reasons such as the possibility to make more money, or lose less of it—that change is far from smooth and can be hard to identify from the outside, because the language itself struggles to move on as well.

The most notorious case is of course the compositing process; something that is still referred to as photographyPhotography (撮影, Satsuei): The marriage of elements produced by different departments into a finished picture, involving filtering to make it more harmonious. A name inherited from the past, when cameras were actually used during this process. (撮影, satsuei) despite having moved on from actual cameras when cel was phased out, which only feels somewhat fitting now as more compositing artists aim to emulate actual camera lenses. While in this case it’s simply a curiosity as no one with even the slightest understanding of modern animation would think that physical materials are still layered and filmed, other processes where the significant changes aren’t so intuitive are prone to serious misunderstandings. And when it comes to those, no situation is messier than the very skeleton of Japanese animation: the layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists..

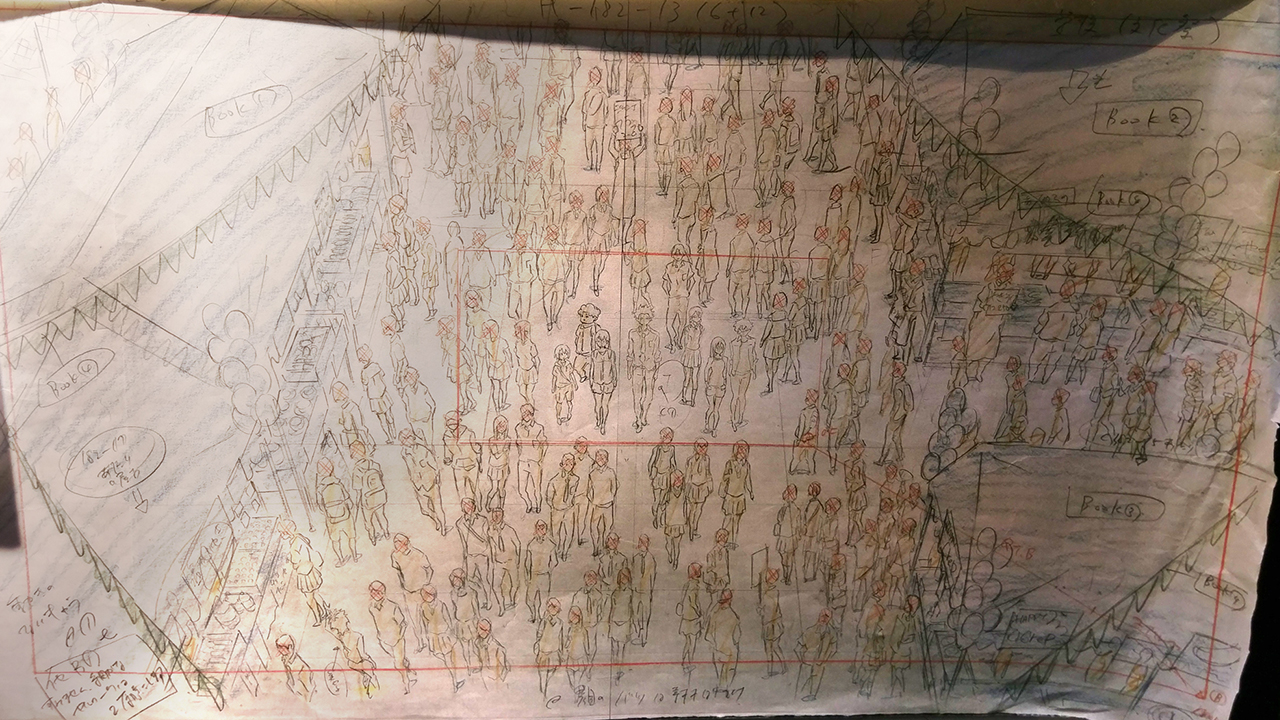

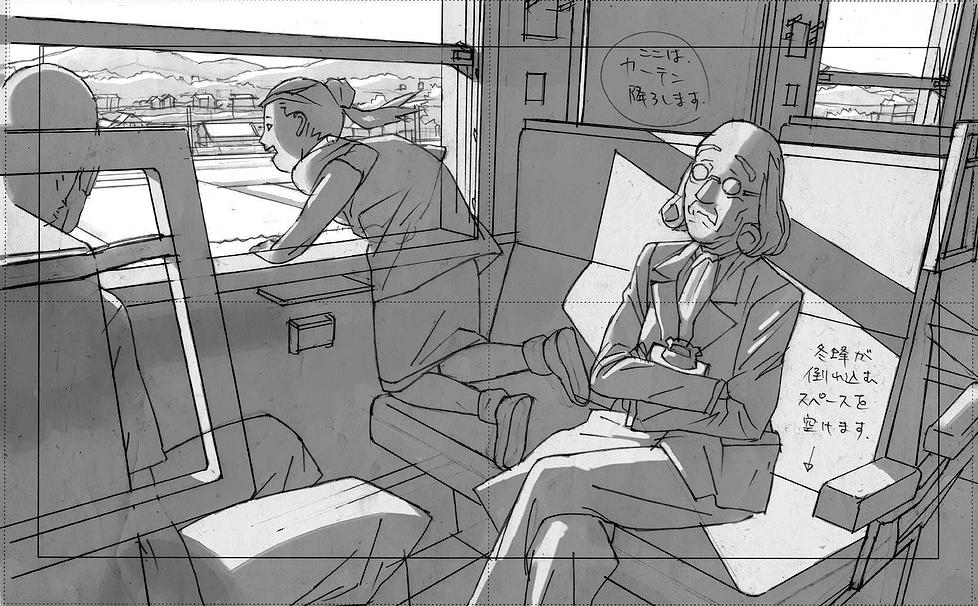

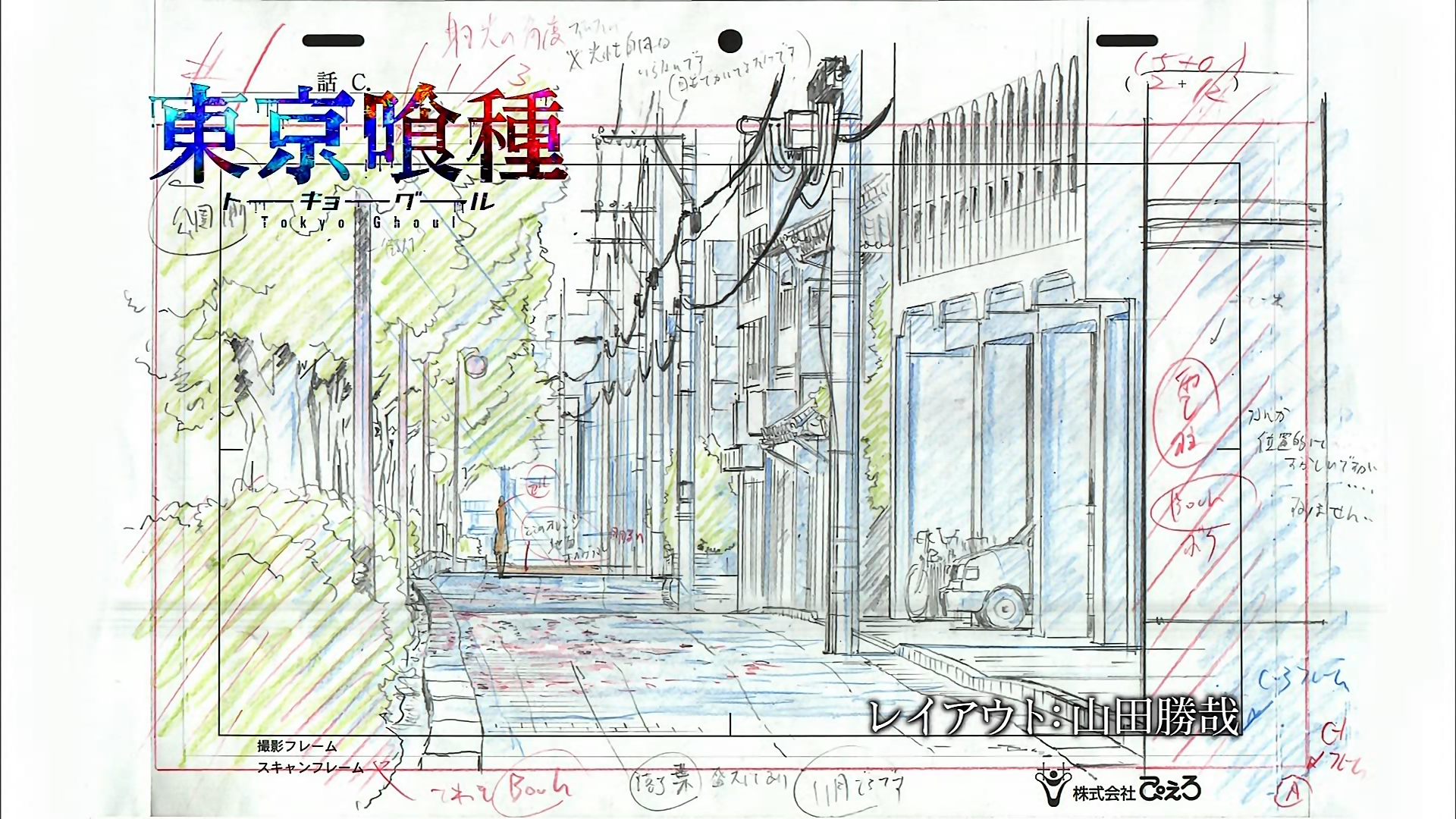

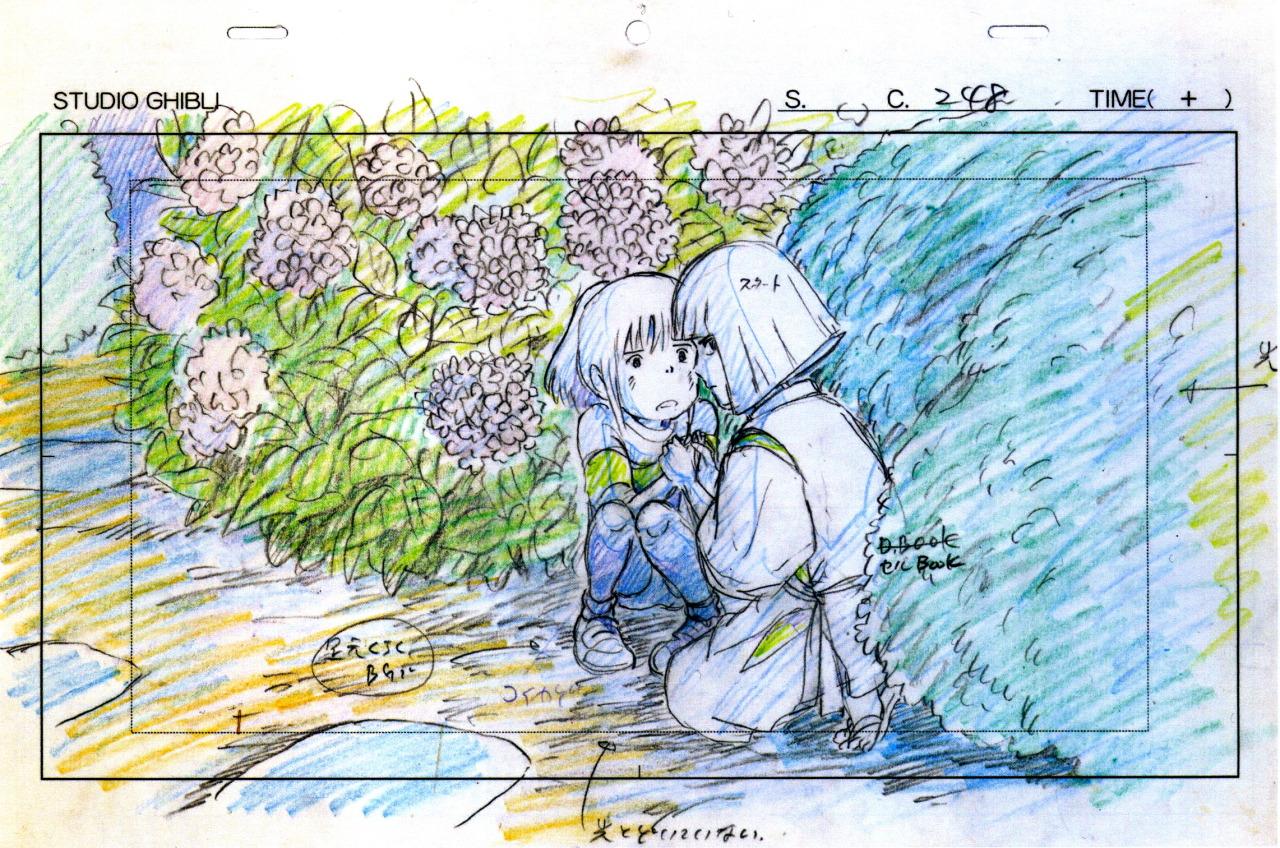

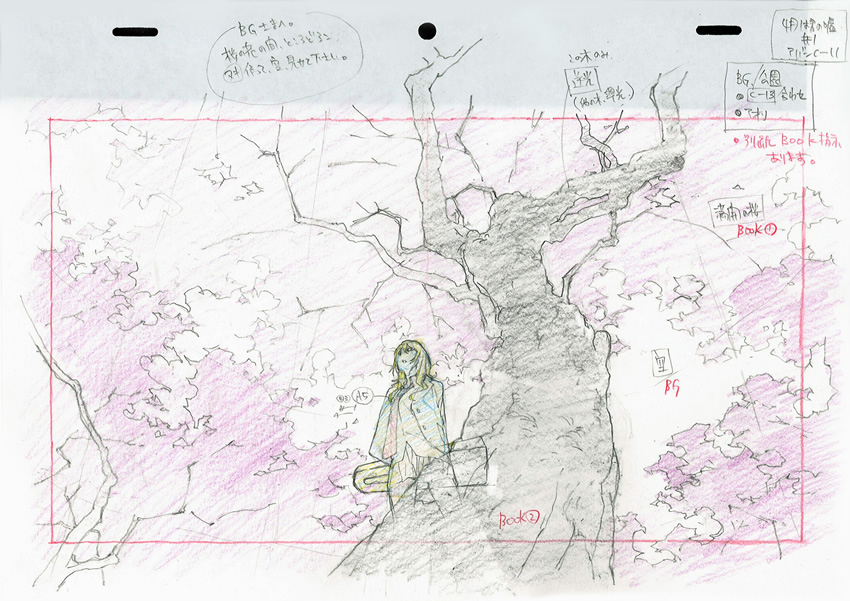

On paper, anime production still sticks to the layout system as established by Hayao Miyazaki for Heidi in 1974; or rather, the more feasible take on it, as no modern project has a young Miyazaki to compose every single shot in their work. While the idea of an animation layout already existed, it was their approach to Heidi that codified the blueprints for commercial Japanese animation as we know it. As you might be aware, that begins with an animator executing and expanding the ideas behind a shot that are rarely fully realized in a small storyboardStoryboard (絵コンテ, ekonte): The blueprints of animation. A series of usually simple drawings serving as anime's visual script, drawn on special sheets with fields for the animation cut number, notes for the staff and the matching lines of dialogue. strip. This includes the composition of the fully-formed cut, annotations for all sorts of staff members that will come into play later down the process, and even guidelines for aspects of the work that will be handled by a different pipeline; most notably, the composition of the background that is sent to the art department. The addition of this intermediate step that gives a very clear idea of what the finished scene will look like turned out to save a lot of time on back and forths and corrections, as a properly checked layout should already put all the subsequent tasks on the right track.

Although you can still find exceptional projects where a single animator handles most if not all the layouts—such as Yuki Hayashi’s key contributions to Kyousougiga—the widespread application of that model quickly shifted to entrusting this task to the key animator in charge of that sequence. This placed a tremendous amount of responsibility on an individual animator, who wasn’t only fully defining the shot through that layout, but also executing the key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. for it. There was an inherent sense of cohesion by having a singular artist envision so much of the final execution of that particular sequence, and for as intimidating of a prospect as that workload could be, that was also the draw for many animators. While working within a larger narrative context and the constraints of a director’s vision rarely equaled complete freedom, animators got to be the protagonists of their own scenes in a way that might even let them forget the poor working conditions.

If that train of thought sounds familiar—as well as that past tense—that might be because you read our 3 years old piece about the alarming fragmentation of anime production, which has all but obliterated that carrot on a stick. Although the focus of that article was narrower, mostly emphasizing the effects that this trend has on key animators, it already alluded to a loss of cohesion and thus the immersive effect of animation. We talked at length about specific events like the appearance and corruption of 2nd key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style., which turned existing tasks like clean-up into a separate job that could be handed to other people—ones who increasingly have had to fill up lankier skeletons of animation.

It’s worth noting that this is a change that has been very relevant to our site. When sakugabooru’s animation archive launched less than a decade ago, we agreed that the information should be shared whenever available, but still made the executive choice of not tagging 2nd key animators for authorship, save for rare exceptions where we knew for a fact that the credit might as well be a misnomer. Flash forward to the current day, and we find ourselves with a more flexible approach as those artists can often be as crucial as even the animation director. Again, the terminology might not have changed, but the nuance is quite different.

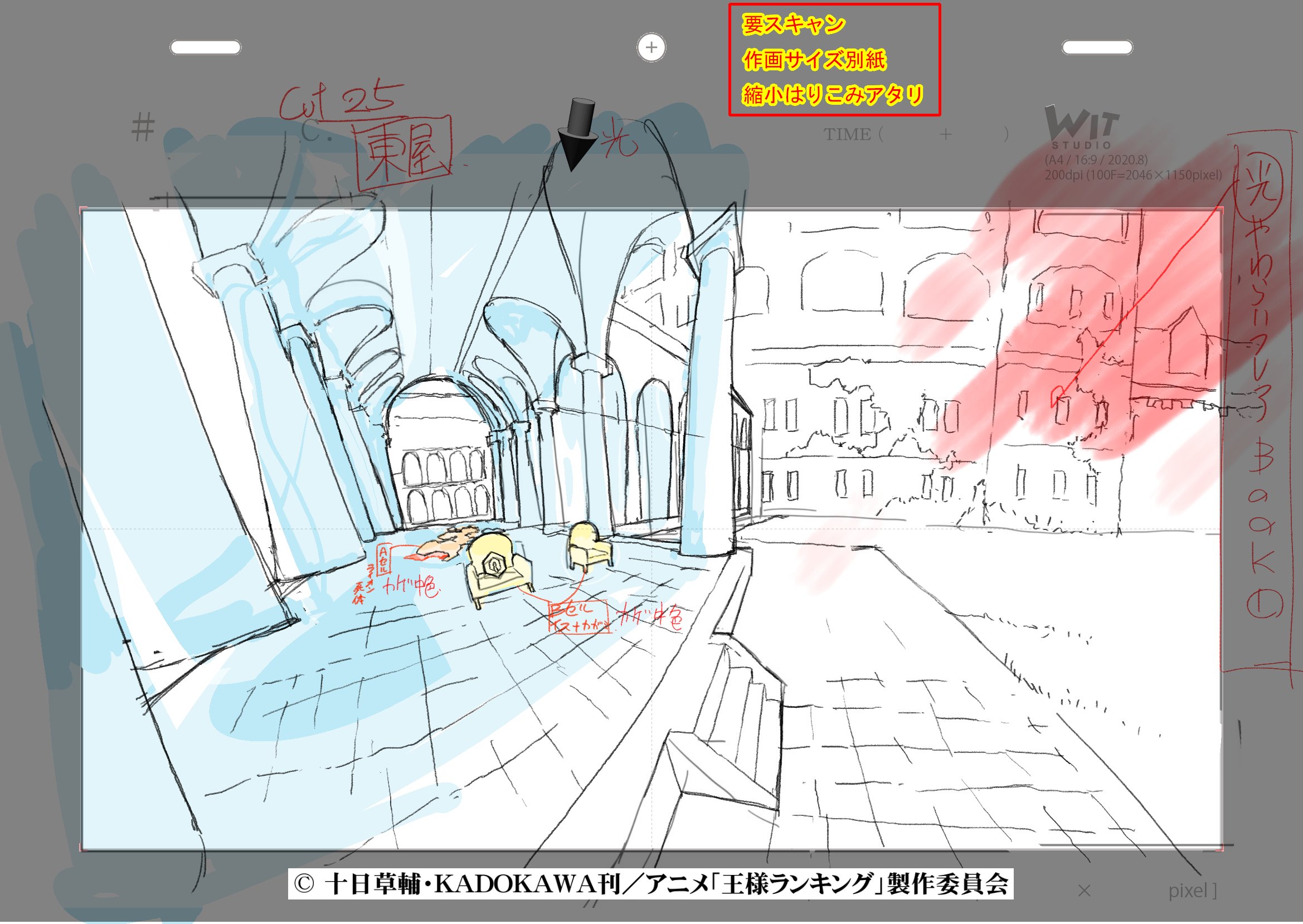

This brings us back to the layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists. themselves. The very blueprints for Japanese animation are undergoing similar changes, with similarly undesirable side effects at that. Although this change hasn’t taken over the industry as a whole yet, environments where digital animation dominates in particular have completely blended the concept of the layout with that of the rough key animation, bundling together two tasks that once had very different goals. While that may sound completely harmless on paper, combining it with other factors like the constantly collapsing production schedules and the industry strongly favoring overly intricate designs and bombastic animation—two elements that don’t play well together—this means that the original goals of the layout process from a creative standpoint are no longer prioritized, if cared for at all.

The technical soundness of the composition and the annotations, the nuance of the framing, and the attention to non-cel elements in the shot get thrown out the window when time is tight, and even when it isn’t, so many jobs are pushed onto young artists with no practical training that all these aspects that aren’t as intuitive as flashy movement no longer receive the love they deserve. And as we’ll get into later, the systems to address these weaknesses have completely collapsed as well. In short, the element purposely designed to be the central pillar stabilizing anime no longer exists as such, and the need to quickly put together a product that’s attractive to as many viewers as possible has crushed the merits that made the layout system worth pursuing in the first place.

Before we get into more specifics about the current situation, it’s important to understand that this is not a binary issue of the peerless immersive layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists. of the past versus thoroughly flat and technically broken modern shots. There also isn’t a single incident that we can point at as the trigger for these problems, but rather an accumulation of changes chipping away at anime’s traditional immersion among many other qualities. While these recent changes to the layout system might be the straw that broke the camel’s back, plenty of other factors have been at play for longer; the anime boom following the digital transition greatly reduced the tactile cel component as animators had less time to dedicate to specific shots, average linecounts skyrocketing make the character art alone a big ordeal, even the increase in screen real state with HD 16:9 production has had its toll. None of these are inherently negative changes: right about anyone can find a particularly detailed closeup in modern anime to be stunning, but as a trend, these changes have been clearly incompatible with the pace the industry demands, and so the changes have come at a large cost.

There is no better way to illustrate this problem than listening to directors and animators themselves. Fortunately—or unfortunately, as it’s telling of the magnitude of this issue—there is no shortage of veterans decrying the current state of the industry. And out of them all, no one is as proactive in trying to address the decay of anime’s layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists. as Ryouji Masuyama. While he’s not as idiosyncratic of an artist as his studio Gainax contemporaries, Masuyama’s fundamentals are so sturdy that he has become a trustworthy regular on high-profile titles at studios like A-1, WIT, and of course TRIGGER. In a way, his figure is completely antithetical to the current direction of the industry; he excels at the foundations that have become flimsy, he’s a mentor in an industry that has abandoned its students, and a mindful colleague and leader at a time where teams are mere collections of individuals.

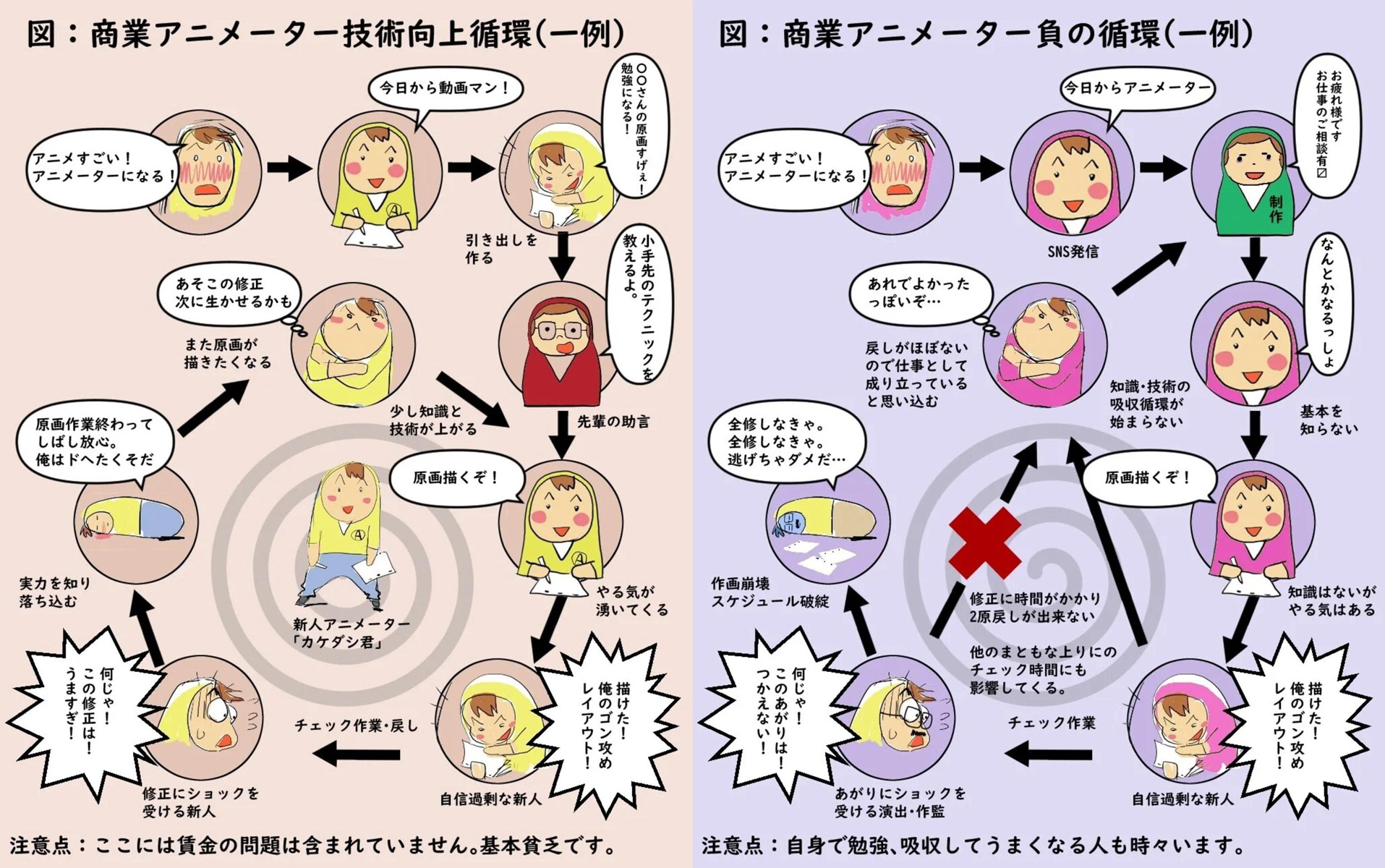

Masuyama has used his platform to denounce these issues and the causes he has found behind them. He directly points at the fragmentation of the workload that we’ve talked about as a critical blow to anime, as it directly impacts the learning process for young animators. In a traditional environment, the layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists. are meant to go through episode and animation directors, who send them back to the animator in charge of that sequence. Ideally, this will not only improve their cuts, but also help the animator understand the rationale behind those fixes; annotations can go a long way, but even simply studying the intent behind the linework can greatly improve the quality of your work moving forward. But what happens if those corrections never make it back to the person who drafted the shot, instead being sent to a separate 2nd key animator in what is known as sprinkling? Masuyama, like many others, argues that the accumulation of knowledge is no longer happening in this now common situation. The original animator never learned of their fallings and potential venues of improvement, while the 2nd key animator isn’t really getting the full story either as they didn’t get to conceptualize the shot.

While many just despair about this, Masuyama has been making an effort to help, even outside of his own projects. He volunteers to hold seminars aimed at young artists whenever he’s got the time, all while publishing all sorts of advice and practical guides to work in the anime industry. He also makes a point to seek information from other industry members as well, as there is no universal truth to anime’s inner workings, and your job should be to figure out the ins and outs of your own pipeline. His layout guide series is particularly lengthy and in-depth. He starts by detailing these fundamental issues in the construction of animation, moving on to technical knowledge, ways to foster the right mentality for the job, as well as plenty of practical advice and mistakes to avoid—the type of knowledge that animation courses often don’t give you, which also isn’t being properly passed down nowadays within the industry due to the downfall of in-house studio culture.

All these issues that professionals like Masuyama have detailed are an internal problem of anime’s workforce, but to get the full picture, it’s worth considering the external pressure they receive as well. One of their most common complaints, not just because of the effect it has when it comes to this topic of immersion but also due to all the creative and labor repercussions it has, is the disproportionate inflation of expectations. The tangible virality of modern megahits like Your Name and Kimetsu has led to impossible expectations being applied across the board by audiences and producers alike, affecting teams that have no business competing with such high-profile titles. It’s no secret—in part because animators will not stop complaining about it—that rather than being a choice by the creative teams, the inflation of linecounts and increasing intricacy of the postprocessing are an unhealthy attempt to match the most easily appreciable qualities of anime’s current cultural phenomena; again, not particularly unique on its own nor an inherently negative trend, but one that is putting extra pressure on an industry on the brink of imploding.

Everyone should know that the casual viewer’s idea that happenings in a particular title are an immediate response to the audience’s feeling is a myth, but at the same time, it’s foolish to believe that the industry doesn’t pay close attention to its customers; or rather, to the twisted image of them projected by social media. I would say that there is no reason to believe that viewers at large are obsessed with polished, hyperdetailed, and stylistically unchanging character art. After all, many all-time popular anime that are remembered as consistent quality products had such obvious stylistic variations on a weekly basis that they spawned animator style charts. If you put too much weight on inherently inflammatory social media platforms, though, it’s easy to convince yourself that most viewers really do have these impossible standards when it comes to intricate visual bombast and strict visual consistency, and thus that fear becomes a factor in many productions. Upon the constant trending of the term animation collapse, even the lead stars of currently beloved shows have to tell themselves that with just one misstep, it could be their own work that is being trashed. And that’s very scary in and industry where, even if you don’t make that wrong step, the ground under you can collapse at any moment.

When it comes to illustrating this link between inflated expectations, cynical stylistic mandates, and simply misguided directions that don’t consider the state of the industry and thus hurt anime’s traditional qualities, few have exposed them as elegantly as Masayuki Miyaji—whom avid readers of this site will recognize him as a creator emblematic of a radically opposed philosophy. Miyaji was a film student who took an interest in animation and underwent training by none other than studio Ghibli, where he went as far as becoming an assistant director for Spirited Away under Miyazaki himself.

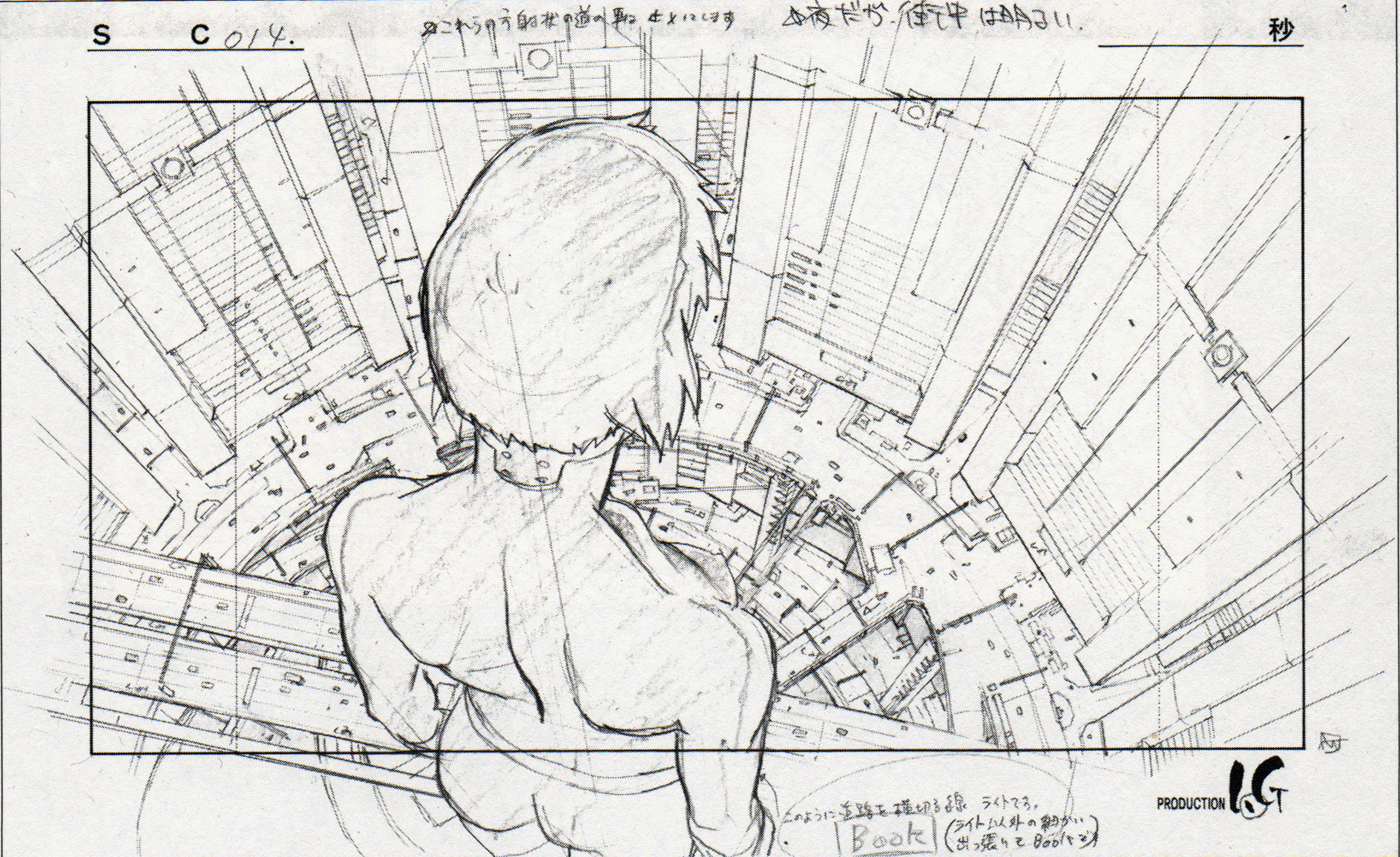

As a freelance project leader later in his career, Miyaji brought animation powerhouses like studio BONES to their knees in an attempt to frame science fiction through a documentary lens; for as messy of a show as it is, the first episode of Xam’d is unmatched when it comes to incidental storytelling through the sheer density of visual information, conveyed through the most stunning layout work you might ever see in serialized anime. His theatrical vision felt anachronistic well over a decade ago, so you can imagine how down he feels in the current state of anime. In a beautifully written stream of consciousness, Miyaji connects many of the dots we’ve gone over—from the inflation of expectations to the failure to properly train new generations of animators—to reach a heavy conclusion: that episode directors might be dying altogether.

Now, Miyaji’s point in that article is even broader, as he navigates all sorts of prickly topics; ideas such as the loss of agency of directors in an era where they’re not asked to challenge the ideology and worldview of the works they adapt, or the double-edged versatility of directors with an animation background, which turns them into handy tools. Despite aiming to make a different point, both broader in scope and more specific in its conclusion, Miyaji ends up touching on similar subjects for an obvious reason: immersing the viewer into a world of its own, with dense and very precisely populated layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists., is what his style is all about. He alludes to that skyrocketing of expectations translating into unmanageable linecounts, which remain a problem even after the size of your average team has grown disproportionately high. He also mentions that fear that has permeated into so many production teams, so terrified of being off-model in an age where that can earn you endless scorn on social media.

According to Miyaji, this has shifted the entire production culture, which is now centered around animation supervision; not the job of animator directors as we knew it, but a much narrower version of it that is all about polishing up those needlessly detailed character drawings. From his experience—Miyaji’s job now mostly consists in drawing storyboards for all sorts of very high-profile anime productions—these animation directors are so busy they have to pass on fixing aspects such as the composition of the layout, the body language, all these fundamentals that your immersion hangs upon. Instead, the checking process falls solely onto the episode director… with the obvious catch that they’re even busier, and as he sees it, in the midst of a process of becoming handymen bereft of vision by design. This is, as seen by one of the greatest experts of transporting the viewer into the world of animation, the fundamental sacrifice that anime’s current circumstances and prioritization force upon creators.

Another obvious conclusion to draw from Miyaji’s depressing view on this subject is that, as you can imagine, crafting an immersive world takes more than just an animator. While we’ve focused on the role of the animator, as they’re the centerpiece of this production system, commercial anime is an inherently collaborative role; as said before, one of the major perks of layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists. as first envisioned was to put people across different departments perfectly on the same page since a pretty early stage. This means that even if you do luck into an animator with those increasingly rarer fundamentals, even a director with vision and the ability to support them, things may still fall apart in the brink of an eye.

A certain skillful animator lamented one such case, where the gorgeous composition they’d crafted was then ruined by an art team that didn’t seem to understand the perspective. The response from a person in that field summed up why that wasn’t quite the case, and how this has become so common: the art crew must have simply lacked preexisting assets that fit that situation, so instead they put together that scenery with the help of contextually inappropriate materials. While smart crutches made easier by digital production are perfectly valid—Tatsuya Yoshihara is king for a reason—these poorly assembled backgrounds that are all over TV anime now are as immersion-shattering as it gets. More than any shoddy drawing, more than any animation error, the space that characters are meant to inhabit accidentally falling apart is the ultimate way to pull you out of the experience.

The truth is that it doesn’t have to be as extreme of a case as that to be a shame, and that very few titles nowadays are safe. Healer Girl might be the TV anime this year I find most encouraging; not my favorite, certainly not the best, but one I’m profoundly glad that it existed. For starters, its production was radically opposed to many of the current issues we’ve talked about. It was in the works for many years, and that’s after the director made it a point to mentor the studio’s animation trainees first. This enabled up to 5 episodes to be key animated by a single person, sometimes with no 2nd key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. whatsoever. And they did so while ignoring all those current aesthetic trends; the designs are fairly manageable, and there were no unreasonable polish demands applied to those episodes carried by singular individuals. On top of that, it had a series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario. like Yasuhiro Irie, yet another household name when it comes to forcefully drag the viewer into a fantasy world through involving layouts—look no further than his iconic Soul Eater opening for that. And yet, despite his storyboards being as sharp as ever and all these positive circumstances, the cel restraint and less than ideal job by an art studio that likely had too much on its plate led to wildly uneven results. Animating an immersive world has simply become this much of an uphill battle.

We could have ended this piece on a downer note like that, but it wouldn’t have painted an accurate enough picture. Now, this isn’t meant to say that all these veterans we’ve quoted are in the wrong; they’re talking about a palpable decay in the finished product, basing their conclusions on their extensive experience making such works. At the same time, though, it’s precisely because they’re veterans who excel at that traditional immersive aspect that they’re more likely to let bad experiences completely cloud over their vision of the present and future. When something as fundamental as whether corrections will be returned to their original animator or not is a flip of a coin, it obviously constitutes a major issue that should be talked about, but that doesn’t mean that we’re in a completely doomed scenario where it never happens and youngsters simply have no chance to learn from their supervisors. Things are demonstrably bad, but has anime’s skeleton truly shattered beyond repair?

To find that whether that truly was the case, we decided to have a long discussion with someone whose point of view is much fresher, while also being knowledgeable about animation and the means to draw the viewer into its world. Though there are plenty of young artists who’d have fit the bill, the person who felt like they could provide a broader view—especially when it comes to the labor dynamics at play—was our good pal Fede. Over the last few years, they’ve found themselves carving out a bit of a new role in the anime industry: a technical translator for storyboards and such production materials, interpreter for staff meetings, and somewhat of an overseas producer, often with another friend of this site you might know as Blou. It’s no secret that their position is enabled by the current chaos in the industry, because for as much as we can idealistically talk about the internationalization of anime production as a theoretical boost to its creative possibilities, the reality is that it’s the desperation of an understaffed workforce fueling this phenomenon. At the same time, people like Fede are the first ones to get a headache from this situation, so you can expect them not to pull back any punches.

Right off the bat, Fede admitted to the problem and corroborated many of the conclusions of the aforementioned veterans, though with a different view on some causes and implications. While agreeing that younger generations who joined an industry that no longer had proper training mechanisms lack these fundamental skills and that not even getting corrections back is certainly a possibility—but not a certainty like Masuyama implied—they pointed at other lacking areas of knowledge as perhaps even more problematic. At the end of the day, perspective and image composition are fairly universal qualities of art, but what about the proper notations in animation production, which are by no means intuitive? Animators are now meant to come to grasp their nuance essentially by themselves in a trial and error process that puts extra stress onto the episode director; and as we’ve discussed, those have too much on their plates already, hence why immersion-breaking instructions and misguided camerawork make it to the finished product more often than they should.

In Fede’s view, and that’s something we agreed about, a way to address that could very well be promoting more compositing staff to episode directionEpisode Direction (演出, enshutsu): A creative but also coordinative task, as it entails supervising the many departments and artists involved in the production of an episode – approving animation layouts alongside the Animation Director, overseeing the work of the photography team, the art department, CG staff... The role also exists in movies, refering to the individuals similarly in charge of segments of the film. duties—something that has been known to happen, albeit to a much smaller degree than your traditional animation and production assistantProduction Assistant (制作進行, Seisaku Shinkou): Effectively the lowest ranking 'producer' role, and yet an essential cog in the system. They check and carry around the materials, and contact the dozens upon dozens of artists required to get an episode finished. Usually handling multiple episodes of the shows they're involved with. paths to direction. For one, that is an aspect of animation that is bound to become a central pillar moving forward, especially in an environment where there are so many lacking areas to mask. And perhaps most importantly, Fede has found that no one is as adept at addressing all the technical problems that are bound to arise, as you’d expect from the people whose job is to assemble all the materials together. As the industry struggles to put together animation in a cohesive, inviting fashion, perhaps this could be the start of a solution.

At this point, it should be clear to everyone that technological advances will not provide a panacea, but we shouldn’t deny their ability to assuage the pain. Look no further than the increasingly more popular practice of providing 3D layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists.. Although enforcing them does have the drawback of limiting the vision of the most ambitious animators, making for competent yet somewhat clinical results, the truth is that it really raises the floor in a scenario where animators aren’t prepared to handle complex interiors. And, applied the right way, they can enable new approaches to animation as well. Some of the funniest work in Spy x Family was the result of the episode directors themselves handling the 3D layouts, letting them board surreal scenarios in the most objective way possible, then properly capturing that contrast in the animation. While it’s not necessarily the most cinematic experience, episodes like this are a perfect example of adapting one’s style to the tools they’ve got available, then figuring out how to enhance the material they’ve been given with it.

As bad as the situation is, there are plenty of examples of digital tools being used to boost those feelings of cohesion and immersion, even when the drawings themselves aren’t as solid as you’d wish. Directors like Shuntaro Tozawa have a knack for inviting perspectives, which they marry with sometimes excellent environmental lighting to draw you into his episodes. When it comes to recent highlights, though, few sources of hope shine as bright as Shota “Gosso” Goshozono, best known for his spectacular work in Ousama Ranking. It’s no secret that he has built his bewitching style on his usage of Blender to conceptualize and draft his 3D-heavy setpieces, but people’s tendency to overly emphasize the software misses the point of his genius. The truth is that, ever since digital pioneer Ryochimo started experimenting with it as a 2D animation tool, many artists have given Blender a spin, but no one has managed to use it to stage something as deliberate and breath-taking as his Ousama Ranking episodes; three-dimensionality comes as a given if you use 3D software, but you need vision like his to actually draw the viewer into those spaces, to use the layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists. themselves to regulate the tension, and of course, to make action this damn cool.

If you’re wondering what the catch is, we just have to go back to our chat with Fede. In their experience, for as well prepared as those compositors turned directors are, their background also tends to have the effect of being overly technical in the explanations of their vision. This marks a stark contrast to animators who approach cinematography in a more visceral and instinctive way. That is the type of friction that you can address in-house, where specific meetings don’t have to be arranged and you can simply swing by someone’s desk, but that is essentially impossible in the current industry, hence why people just can’t seem to be on the same page—and if we’ve learned something there, is that you can’t create a believable world that will draw viewers in if the staff doesn’t see eye to eye.

What about the likes of Gosso, though? Don’t the passionate young animators who approach the process from a fresh direction get to bypass these issues? As we’ve seen, they absolutely can do that… but they will never be the norm. Individuals like that are essentially rebelling against a system that pushes them in the opposite direction. Fede explained the very depressing bottom line: ultimately, nothing has become more limiting for animators and directors than the money, both its pitiful amounts and the way it’s paid. For an animator who hasn’t made a name for themselves, the low remuneration that only factors in the number of cuts according to the agreed rates is simply pushing them to accept as much layout work as possible. Not to spend time envisioning how the backgrounds and characters perfectly come together, not sticking around to finish some tricky 2nd key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. according to the corrections and thus learning in the process, but rather quickly grinding subpar layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists..

And in a way, the situation is even worse for episode directors. While the rates for animators are somewhat on the rise in cases where the studio is desperate, the rates for enshutsu have barely updated at all, even though their job has become a nightmare as of late. Not only are they the ones supposed to fix all these fundamental problems we’ve gone through, but they’re also victims of the uncertainty of the schedules; with the constant delays, projects slowed to a crawl due to the pandemic, and now common similar issues, what was once 150~300k JPY for 4~6 months can take much longer with no real compensation, other than perhaps a binding fee that will not make up for their desperate need to juggle multiple projects. In the process of editing this piece, we were contacted by an independent party who had recently spoken to an anime director, being told that is no longer financially viable to handle both storyboarding and episode directionEpisode Direction (演出, enshutsu): A creative but also coordinative task, as it entails supervising the many departments and artists involved in the production of an episode – approving animation layouts alongside the Animation Director, overseeing the work of the photography team, the art department, CG staff... The role also exists in movies, refering to the individuals similarly in charge of segments of the film. duties—the traditional, creatively ideal scenario—so they instead focus on the boards; something that might pay a little worse, but that is much easier to churn out. The most cynical voices in the industry point at directors like that as uncaring, but it’s the current model that has forced them not to care.

At its core, this is the same old problem. The industry’s issues are never only about money, but they always are about money. That is what a veteran like Masuyama concluded, and similarly, how our chat with Fede ended as well. It’s arguable whether anime’s business model was ever compatible with a unified, creative workflow. What is beyond questioning, though, is that right now it’s actively boycotting it. Let’s be real: it’d be naïve to expect any change just because this entire process of fragmentation and loss of staff agency is creating friction within their work, because as long as the industry can put out flashy products that are popular, no suits will see an issue worth addressing. But as Fede pointed out, they might be in for a surprise when the freelancing model implodes on its own, as managing hundreds of negotatiations on almost a weekly basis and the upcoming in-voicing changes in Japan feel like a ticking bomb that will hurt everyone involved.

So in the end, what exactly happened? A combination of factors, very few of them positive. Anime’s lack of adaptability has made it stick to a production system that is no longer sustainable given the industry’s levels of output, losing the upside of their specific approach in the process. Similarly, business and management models that somehow worked out in the past are now asphyxiating companies that keep acting the same way out of pure inertia. While the dynamics of commercial Japanese animation have a built-in practical mentorship spin to them that could address the lacking fundamentals of the newcomers, excessive fragmentation of the process and the collapse of studio culture have broken that learning cycle. And, even if they hadn’t, a more fundamental problem haunts everyone: the employment model, or rather the lack of thereof, actively incentivizes animators and directors to blaze through quick jobs rather than dedicate meaningful time to specific scenes that aren’t the designated action highlights. Given how needlessly complex animation has become by chasing megahits that your average title has no business even comparing to, that inability to dedicate yourself to a specific job has broken the backbone of anime, the one where the entire illusion of animation rested upon. While passionate individuals and some inventive applications of new technology can address that, at the end of the day, this is a creative problem that can’t be solved without addressing the many labor issues lurking behind.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

Your blog is incredible, thank you so much for these posts. As someone studying animation your blog is a goldmine.

Thank you for the in-depth, clearly written article! And the links to Masuyama’s essays. Excited to read them, and that that knowledge is being preserved. From the standpoint of ‘how can we improve anime?’ I think posts like this are worth their weight in gold for weaving together so many different factors and issues into a single narrative. IMO the layout–not animation–has been anime’s strength historically, and so it’s a shame there isn’t more discourse and celebration of the former. You think about how sakuga culture has birthed some really innovative animators, and have to wonder what a similar layout-oriented… Read more »

That was long. Not only I had to read the whole article twice, but also needed to go through some sentences and paragraphs thrice or more to understand to full of it. Probably my weakness in language is showing, but regardless, thanks a lot for so much elaboration. I am at awe about xam’d and also a bit curious about what happened next. Those layouts are fantastic, but they outright scared me. That much vision and ambition should put inhuman toll on the rest of the team, even if I try to convince myself thinking the production wasn’t this much… Read more »

Not an expert here, but when you talk about ‘inhuman toll’ on Xam’d I think it’s really a question of skill: if the staff were good enough and schedule allowed it, Xam’d level layouts wouldn’t be a problem (check out GITS 2 or Wolf’s Rain). Selfishness is not ambition, but wildly unrealistic ambition–a director creating a workload that the skill level and time on the production couldn’t concievably allow to be completed. Broadly speaking, I do agree with you: More, more fun movement was one of the reasons Pokemon S&M switched to simpler character designs, so I think it’s fair… Read more »

Hello. – Hello.

I am an anime lover living in Japan.

I believe your astute points are useful even within Japan.

If possible, may I translate your article and post it on my site?

My site is here.

https://trend-tracer.com/

*Translated using DeeL.

Thanks.

Fine as long as the original article is sourced and linked!

Damn, that was brutal to read

I guess my question to you is, what happens when it collapses? And what’ll emerge or remain when the dust clears?