The Two Chainsaw Mans – CSM Production Notes 01-03

Tatsuki Fujimoto’s storytelling is spontaneous, anarchic genius, so how should one adapt Chainsaw Man into anime? Its team committed to a vision that has made two takes on the exact same story feel quite distinct, so let’s dive into the anime’s production to explain how and why that happened.

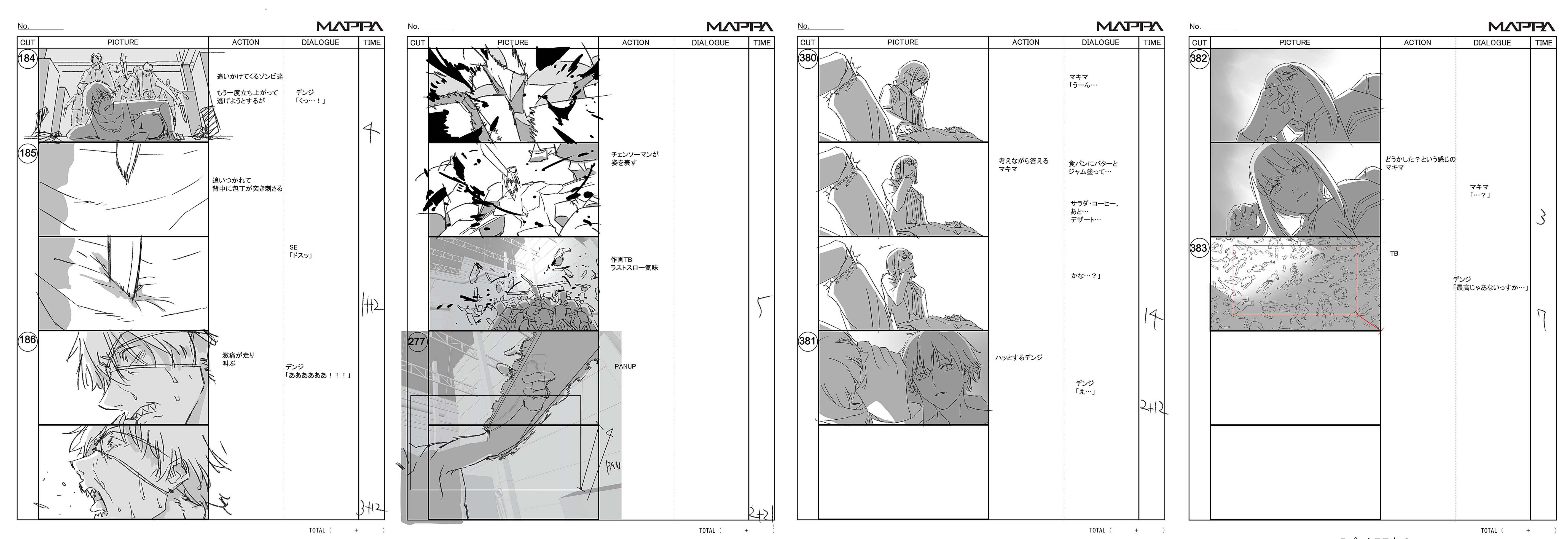

Tatsuki Fujimoto is weird. That’s something I was aware of after following Fire Punch during its serialization years ago, and having since then read not just Chainsaw Man but quite literally all his published works, I’ve only come to appreciate his eccentricity more. While the spontaneity of his creative process, his eclectic influences, and the belief that he’s creating for a public who’s gotten bored with standard works contribute to this, much of that oddness is clearly inherent to Fujimoto; again, he doesn’t act weird, he is. Before you even get to the wild contents of his works, the very grammar of his comics—not just the paneling in a strict sense, but also the pacing of his delivery—is bewitching, clearly drawing from many of his influences yet amounting to something that feels unique. As a reader, I adore all of this, and if I were entrusted with adapting it to a different format, I would dread it. And that’s precisely the challenge that Ryu Nakayama decided to accept.

During our seasonal preview, we already introduced Nakayama’s figure at length, explaining why a newbie series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario. like him was conversely a reasonable choice to lead such a massive project. Given the technical mastery of his animation, his magnetism with other cream of the crop industry members, plus a willingness to break the mold and commit to a vision that we’d seen hints of in his admittedly limited body of directorial work, MAPPA producer Keisuke Seshimo got quite the interesting prospect in his hands.

As mentioned in their conversation published in the November 2022 issue of Nikkei Entertainment, Seshimo approached him during the production of Jujutsu Kaisen, where Nakayama was due to lead the 19th episode. He had thought that, given the opportunity to handle a project from scratch, he’d much rather do so under an external director of his own choosing than with MAPPA’s own personnel—and being an animation geek himself, he was well aware of those qualities of Nakayama we’ve highlighted. In Chainsaw Man’s anime start guide, the director admitted that Seshimo had pitched other ideas before, but those hadn’t materialized. Nakayama was mindful in the selection of his series direction debut, and yet he took this offer the second it was presented to him, despite being fully aware of all the hurdles that awaited him. As a fan of Fujimoto since Fire Punch, he couldn’t pass on this opportunity.

That inertia carried over to the planning process. The second Nakayama gave green light to Seshimo, the two immediately began assembling a team around them, and things never slowed down since then. Although there are slight discrepancies in how core members recall the process—in contrast to this recounting, writer Hiroshi Seko’s guidebook blurb mentions being first inquired by MAPPA CEO Manabu Otsuka in March 2020—the conclusion is that they got the production going in just a couple years, which is rather fast for a title of this exceptional caliber. In another conversation between Nakayama and Seshimo published in the latest issue of Animage, the former alluded to an amusing reason that enabled that swiftness: a déformation professionnelle that makes him wonder how he’d adapt something into animation when experiencing a new work, which led to him already having a preconceived vision for the show before even knowing that it would exist. So, let’s move on to the first episode to see what that entailed, and how it has manifested.

Right off the bat, the anime takes a grounded atmospheric angle to put you in the shoes—eyes?—of its protagonist, Denji. Its production muscle is apparent right off the bat through individuals like animation director and key animator Souta Yamazaki, whose contributions to these early scenes have a tremendous sense of presence and volume; inherently positive qualities of the animation with the added benefit of making the switches to 3D assets less jarring. The team had aimed in this direction in the first place, with the appointment of noted CSM diehard Kazutaka “totos” Sugiyama as the character designer. In contrast to Fujimoto’s raw, spontaneous-feeling drawings, Nakayama opted for a designer whose characters felt perfectly well-defined, tangible, and full with the lineart alone.

These early stages of CSM, as we follow a boy with a life so pitiful he lacks the experience to dream anything but the most standard pleasures, feature all sorts of talented animators who can shine in a scenario like this. You’ve got the likes of Keisuke Kobayashi, perhaps the most thorough animator on Japanese television at the moment, and Takuya Niinuma, known for granting any drawing with lifelike volume through his shading. A tremendous amount of effort is dedicated to making it feel like these characters are really there. And that was precisely the vision that Nakayama had for this series: Chainsaw Man filtered through a lens of cinematic realism.

If there is one thing that the director has repeated over and over in interviews, because it’s something he repeated over and over to his team, it’s that he wasn’t aiming for an overly anime-like take on the material. As a long-time fan of the author, he finds his works to be inseparable from the movies that inspired them, which made him want to commit to a photorealistic recreation of live-action cinema to a degree that no other anime did before. Regardless of how you feel about this adaptation, understanding this is key to grasping essentially every choice they’ve made. When asked to translate that general idea into specific guidelines, Nakayama brought up aspects like the thoroughly down-to-earth palette; in other anime titles with live-action influences, you’ll still often see stylized colors to make the work pop when deemed necessary, but he saw those as concessions that he must avoid. From his demand for naturalistic voice acting to banning manga-like expression shortcuts like sweatdrops—hope that rule doesn’t apply during car crashes—his vision for this title has always been all about animating live action.

Nakayama’s storyboards also make appropriate film references, like the ride that’s about to send Denji’s life into disarray mimicking a similar situation in Ari Aster’s Midsommar, including the very physical camerawork that movie punctuates its turns with. Given a certain painting in the show, though, in CSM’s case that technically ends up amounting to a lesser evil for him.

This philosophy extends to the action sequences as seen in this first episode as well, which turned out to be one of the more controversial aspects. Fujimoto’s work oscillates between moments where the hyperviolence veers into expressionism, and snapshots that are very straightforward about the glorious carnage, which he sells with his excellent compositions. None of this really applies to Nakayama’s CSM, which instead reimagines those moments as involved action setpieces, with pretty fun choreography that takes you on a rollercoaster ride you could slot into one of the Hollywood blockbusters that the author loves. Their dynamism and the titular antihero’s design necessarily involve the usage of CGi, a choice that hasn’t sat well with all viewers… and also has become the source of many misunderstandings. While I would agree that it greatly reduces the visceral appeal of CSM’s mayhem, the truth is that people clamored about CGi in sequences where much of the animation they presumed was computer generated was actually 2D in the end. Mind you, this is a pretty deliberate trap they’ve fallen into; the finishing of the show makes both types of animation meet in the middle to facilitate the switching, which can also cause viewers to mistake one for the other as the tells are minimized.

As the first episode wraps up with the arrival of Makima, right about everyone should already know whether they’re going to enjoy this grounded reinterpretation of CSM or not. Personally, I’ve never hidden that it’s not the angle I’d have approached Fujimoto from. For as much as I support proactive adaptations with an actual vision, I don’t find this to be a particularly bold one, which is what I’d have preferred for a series as idiosyncratic as CSM. Even in this position, though, I find myself enjoying aspects that are naturally derived from Nakayama’s sober approach. Fujimoto’s madness might have asked for a very different soundtrack, but when it comes to the more sober anime, Kensuke Ushio’s very situational score elevates every scene it so much as grazes; and once again, he’s also responsible for the most interesting formal experiments, as he took the chainsaw theme to heart and chopped the waveforms of the songs he’d composed as if he was wielding Pochita himself. Nakayama stated that working with Fujimoto should involve treading new ground, as his manga always feels like a fresh experience, and Ushio is right about the perfect choice for that.

Regardless of your feelings on the artistic choices they’ve made, it would be unfair—or rather, already is, as bad actors have attacked some staff members—to misconstrue this as the team hating anime or not respecting CSM itself; you know, that series they’re all huge fans of. Anyone who knows Nakayama is perfectly aware that he loves anime, but if that needed any confirmation, he went out of his way in the aforementioned Nikkei interview to speak of his own experience growing up within this subculture. Nakayama belongs to the generation of the Suzumiya Haruhi boom, which saw titles that at the time were associated with gloomy loners become the big talking topic of entire classrooms. Thinking that a title like CSM has the potential to take it to the next level, he’s trying to make a show that everyone can enjoy regardless of their experience with anime—an attitude many people could get behind.

Frankly, if there’s a position that strikes me as actually cynical, it’s that of Seshimo. Although he’s undoubtedly MAPPA’s best producer, his statements in publications like the guidebook run counter to what CSM should be in any form. He outright stated that he’s around to stop the show from becoming too extreme and peculiar, because while creators have been exposed to so much art that nothing will be so radical as to scare them away, your average joe might only want to look at beautiful, polished drawings. This belittles right about everyone; Fujimoto, as someone who’s always genuinely dedicated to his nerdy passions, but also a massive CSM fandom that loves a proudly weird work as is.

Why be afraid of scaring away viewers with rough edges, in a project with no external committee pressures at that, when the original author has gained a pretty much unheard-of following with those, if not because of them? Even if we don’t always see eye to eye, I have nothing but respect for a director like Nakayama who will commit to a vision, but producer cynicism is always a bummer.

With the knowledge of what this team is aiming for, as well as the motivations behind those decisions, we can move on to the next episodes to examine the contrast between Fujimoto’s storytelling and this team’s approach. While he loves cinema in all of its forms, his delivery is not defined by the prestige western titles that this show tries to mimic, but rather by his more niche passions. Fujimoto has famously credited the unpredictability of his stories to Korean films like The Chaser, where the titular pursuit is wrapped up before the end of the movie, and thus you’re left guessing what will happen next. If that’s a factor on the macro level, his moment-to-moment delivery is arguably even more influenced by his unashamed love of B movies. The unique grammar I mentioned at the start has Fujimoto constantly operating on multiple, sometimes conflicting registers; be it dumping the protagonist’s dismembered remains in a frankly funny way or, interrupting a fight with the fate of humanity on the line because you crave a burger and some DDR.

In that regard, the anime’s more one-note restrained approach does feel like it’s losing Fujimoto’s magic, but I’ve found myself smiling at the new surrealism born from a straight-faced delivery of his deranged script. I would be lying if I said that the anime is joyless or detached in the first place, and the second episode by Touko Yatabe—assisted by chief episode director Masato Nakazono—is proof of that. The care put into Denji’s nasty breakfast of dreams, as well as original additions that perfectly sum up the character dynamics, tell you that the team really does understand the cast and what’s important to them. And if you want a demonstration of the fun they’re having with it, I could point at Denji’s iconic foul counterattack. Not only does it have some of the best character animation in the episode courtesy of Yoshihide Ideue, but they also added a metallic sound effect to the kick in reference to the Japanese golden balls slang for testicles; and to top it off, they proceeded to crudely type the word with the first character of the voice actors for the unnamed cops in the episode. You simply can’t separate CSM from its juvenile spirit, and even a serious adaptation finds ways to have its fun.

Another defining element of Fujimoto’s unique delivery that the anime is taking a different approach to is the modulation of time. As a mangaka, he fully exploits the format to derive humor out of the pacing itself. Fujimoto will use repeated panels to a degree that defies common sense, dragging out dumb jokes that become funnier the longer he keeps them up, then turn around with the same energy and abbreviate events in such a way that the immediacy becomes very funny—even if the actual event is a scary one.

Anime isn’t as natural as a canvas for that, and given his grounded approach to other aspects, Nakayama doubled down on a linear, constant, and coherent passage of time. A good example of this disparity comes at the end of the second episode, courtesy of Power and her mastery of the hammer. This was originally one of the funniest sequences of pages in the manga, a perfect example of how Fujimoto exploits immediacy; ridiculous developments happening so fast that you can’t help but laugh in amazement, which mirrors his overarching storytelling too. In contrast to that, the anime’s recreation makes the more technically correct choices for its medium: by adding resistance to the hit and slowing down that smash, the sense of impact is increased. Both works execute essentially the same script in a way that best reflects what they are: one’s a chaotic ride, the other a very premeditated spectacle.

The end of this episode also marks the arrival of a cornerstone of this adaptation: the multitude of ending sequences. For those who aren’t pleased with the direction of the series, it’s easy to point at these and claim that they get CSM better than Nakayama does, but that’s doing the director a tremendous disservice. The ending of episode #02 was an essentially solo job by Hitomi Kariya and studio Colorido. With her gorgeous colors, looser expressions, and textured drawings that feel way closer to Fujimoto’s rough style than the solidly drawn anime, she nailed the found family aspect. With his ending for episode #03, Maxilla’s Yuki Kamiya matched the eclectic nature of Fujimoto’s original work and a Maximum the Hormone song that couldn’t be any more fitting. And of course, there’s the exceptional opening by Shingo Yamashita that I neglected to talk about because I already said my piece; a barrage of homages that embodies not just Fujimoto’s love for cinema but also his constant non-sequitur turns, twists on his usual techniques to represent the darker side of this series, all wrapped up in his usual sleek editing. A sequence that might very well be the most thorough translation of Fujimoto’s unique appeal.

If you’ve read the manga and want to see how Yama twists the knife, pay attention to where Makima’s gaze is directed in the fourth cut here. And if you haven’t pay no mind to this and return in a year or two, whenever you want to feel sad.

So, is it a coincidence that Nakayama’s idols and pupils are nailing aspects of the original work, while his own interpretation strays away from it? Of course not, and this shouldn’t even be up for debate. Nakayama is clearly aware that he’s doing something of his own, and despite being so committed to it, he’s willing to balance it out with these stylized sequences that capture qualities from the original in a more direct way. Leading to CSM‘s broadcast, and even more so once these endings began dropping, some people have expressed their frustration that the show itself didn’t embrace these vivid palettes and bolder drawings, which feel particularly close to the manga volume covers. As much as I get the sentiment—these endings are the anime at its most visually appealing as far as I’m concerned—I think there’s an important distinction between artistic choices and artistic goals, which Nakayama has also echoed.

When asked about whether he’d deliberately chosen a young and inexperienced cast for the series, the director explained that he didn’t particularly care about that choice, but rather that it was a consequence of his goal; he wasn’t making a point about fresh talent, it just happened to work out like this because youngsters are less likely to be accustomed to the anime-like acting he wanted to avoid. I feel similarly about the idea that CSM must use very bright colors because that’s what Fujimoto did with the manga volumes. All the author is doing there is trying to capture CSM’s vibrancy into a single eye-catching illustration, hence why such colors make sense—but that’s a feeling that the comic already evokes in black and white, so it clearly isn’t a mandatory step. Would have a more chaotically Fujimoto-like CSM anime been better served with bright colors? I’m inclined to believe so, but the fantastic opening already proves that you can match that energy with a relatively understated palette. Would Nakayama’s take be better with bright colors? That would likely feel incoherent to every other design choice, which means that I now kinda want to see it because it sounds funny.

As if to add some of that spice that people were missing, Hironori Tanaka arrived to lead the third episode as the director, storyboarder, main animation director, and top key animator. Those acquainted with his modern output might be aware that he isn’t just theoretically compatible with Fujimoto’s anarchic hyperviolence—he has quite literally been making Chainsaw Man before Chainsaw Man. As an animator best known for his fluidity, a trait he coincidentally shares with Nakayama, many fans weren’t aware that he also happened to be a tremendous illustrator; after all, why would the ace animator known for drawing flowing hair as if it was liquid and smooth body motion also be a beast when it comes to detail.

It wasn’t until more recently in his already long and hyperactive career that he started finding the time to sometimes settle in specific productions for a while again, and also being given the opportunity to be the leading voice in specific episodes. With the right—which is to say gruesome—material, his supervision proved to evoke visceral reactions like no one else’s. Sharp yet still organic drawings with gushing blood and extreme posing feel exactly like the ingredient that the CSM anime was missing, an influx of energy that still doesn’t betray Nakayama’s more grounded vision. For as strict as he’s been about realism, the series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario. has always been looser when it comes to the devils, who frankly have no reason to be subjected to the laws of this world; which is to say, rampage away, Chainsaw Tanaka. But not too too much, or else you’re going to be corrected by the rest of the team because you drew the marketable girls too spooky. Not a what if, incidentally.

With the anime wrapping up its introductory episodes, it feels like its identity is well-established already. Its one that differs from Fujimoto’s off-kilter, sometimes downright manic storytelling, despite very few changes in the narrative having occurred. If you’re in for a cool time with a still goofy script, Nakayama’s cinematic realism should more than please you, especially given the sky-high production values thus far. If you’re the type of preexisting fan who simply can’t separate the author from his fascinating weirdness, or simply looked forward to this adaptation because you’d heard of the manga’s idiosyncrasy, you might find the result to be lacking. But as we’ve covered, and at the very least when it comes to the series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario. himself, this approach comes from a genuine desire to reach out to many viewers through some of the original author’s beloved tools. As long as it continues to be an interesting project, even if that is partly derived from the friction with commercialism, we’ll continue to cover it over here. How else would I get an excuse to share more Power clips, really.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

While I’m not a fan of the manga/anime’s narrative (and character designs), I am intrigued by the setting and composition of the anime series. I do not want to sound negative but while I don’t enjoy the CGI in certain scenes, I understand why it’s being used. If anything I hope Granblue Fantasy gets a 3rd season and hopefully Nakayama directs it since he has a great sense of setting with certain vibrant colors. That and the storyboarding for the action scenes. Not in terms of “choreography” but overall movement. How does one portray that in storyboards? It doesn’t seem… Read more »

I’m sorry if my response offended anyone. I was just asking some questions.

I was a bit startled at the beginning seeing how you started saying everything from a complete first-person perspective. That’s rare, since in most of the articles you form the sentences in such a way that sounds more like general objective evaluations. Was that to avoid controversies, like telling the fans it’s just your subjective take on the adaptation? I very much agree with your take on the anime though. I now do understand the reasoning behind why the director took the visually grounded approach, but I still don’t agree to it. While making the anime look like a photorealistic… Read more »

I tend to switch when they’re personal posts and I’m emphasizing that it’s my reading, which was bound to happen on a piece like this where I took a collection of interviews and other bits of info, then used them to contrast my view of both takes on CSM. It’s not something I actually pay much attention to though, lol. Maybe I just felt lonely because I’m the only person on the site who really cares about the series?! (no longer a valid excuse since Dis binged the manga this week and enjoyed it lots). And yeah, some truly eye-rolling… Read more »

oh hey, can you convince him to idle in the dead IRC? it’s flat dead, so once in a while I get a jolt to ask him if he’s still suffering from that problem he set in the /topic, but I guess he left the channel forever.

Do you think the director will change for the next seasons after all these criticisms?

This is the first time I see an anime being attacked so much by Japanese fans

Hell no. The reaction might look bad if you’re deep in the fandom, and believe me, it absolutely does suck that some people are getting harassed over making a high-quality product that just doesn’t happy to be the embodiment of someone’s impossible dreams. But at the end of the day, this is but a tiny fraction of a massive fanbase that is clearly loving such a fancy adaptation. It’s true that some of the reaction feels kinda unprecedented (seeing an acquaintance get 200+ aggro QRTs from the JP side of things for a pretty innocuous comment was crazy since that’s… Read more »

As someone who has read the manga in it’s fullest and still is following, I am very much pleased with this adaptation. Even if I see where people are coming from, I disagree very hardly with the claims that the fights are “boring” compared to the manga or that the style of the manga is lost in adaptation.

It’s frustrating that out of every one of Fujimoto’s works, Chainsaw Man is the one being adapted using a live-action, cinematic approach. This style would have been more appropriate for any of his other mangas. Goodbye Eri and Look Back are obvious choices considering their grounded explorations of why we are driven to create art. Goodbye Eri in particular is a perfect fit as the paneling emulates videos taken with a handheld phone. Even Fire Punch would have benefitted more from this style than Chainsaw Man. Despite Fire Punch’s hyper-realistic brutality and absurd narrative direction driven by a refusal to… Read more »

Another great read! I’m quite torn on the adaptation so far. While the cinematography and realism is well done and captures the film influences Fujimoto imbues in his manga, I cannot help but dream of a different Chainsaw Man adaptation, one that leans into the more surreal and visceral side of the manga like what the third ED shown. Hell, I think even Fire Punch would work better with the film aesthetic, since even with how deranged FP was it had a certain groundedness to it CSM didn’t have as much. It’s a pleasant show so far if you separate… Read more »

I have hope that the increasingly more deranged narrative will push not just for the animation and visuals as a whole, but also other aspects towards surrealism. There is one otherworldly (or rather netherworldly) setting in particular that I think is tailor-made for Ushio, since he can make literal chainsaws clashing sound somewhat ethereal. Even from Nakayama’s angle, there’s room for more experimental work once the series basically loses any semblance of normality (if it ever had any, lol).

As someone who hasn’t read the manga I can’t comment on CSM as an adaptation. But I have read Fujimoto’s more recent one shots and didn’t really resonate with their quirks, the repetitive paneling and all that. I’ve enjoyed CSM a lot so far and was happy that the first episode was serious and focused so much on getting you emotionally attached to Denji. The animation and attention to detail has been insanely impressive. At least in the Western community it would seem that Nakayama’s decision to ground CSM more in realism to reach a wider audience has worked. It’s… Read more »

You’re quite literally the person it was made for then, no shame in loving it, lol. Maybe I’m biased since it was my first exposure, but while CSM is overall the stronger work without a doubt, I think that Fire Punch is still the best series to become acclimated to Fujimoto’s quirks and grow to appreciate them. His more modern output can stand on its own thanks to other qualities, but Fire Punch completely falls apart if you detach it from his bizarre delivery. It fully embraces his Tsutomu Nihei influences around the end too, so anyone who enjoys his… Read more »

I’m not a reader of the manga, but I did somehow come in with the expectation that visually it would be a bit more wild and experimental. That there would be more, I dunno, pop?

But it might be because of the manga cover — I had seen that and it is a bit … impressionistic.I’ve also watched a lot of Ikuhara lately and that’s had an effect on my animation sensibilities perhaps.

As it stands I think CSM looks solid visually, just a bit clean for my tastes.

Ever since I knew who the compositing director would be, I was skeptical about director Nakayama’s vision, which you named very well with cinematic realism, and I totally disagree with this vision of the manga that nakayama chose: the colors and the composition, are completely out of place, despite the colorful manga Chainsawman having similar light colors, there it is more harmonic and bolder. I also believe that the direction of the voice acting is also wrong, castings to support his selfish vision of realism, will greatly limit the reach of Chainsawman’s success. Finally, I must say that the title… Read more »

My personal opinion, I think this anime series “animation quality” & storyboarding would benefit from the “Kanada” style of animation. You know like Takeshi Maenami or Yuu Yoshiyama. A focus of dynamic poses of characters especially their actions.

You practically read my mind, and I would add one more to that list, Kai Ikarashi, that one would have the intensity in animation needed to adapt chainsawman, that’s why I was frustrated with his participation in the Cyberpunks anime that Trigger released recently, it was an energy channeled in the wrong place.

I’m not sure if Kai Ikarashi is working on another show atm. Especially since a Gridman movie is in the works. And who knows what else Trigger’s got cooking. I know I suggested Takeshi Maenami or Yuu Yoshiyama to work on the CSM anime but idk if those animators are flexable these days. Cause I doubt Maenami will EVER work on anything Pokemon relate ever again. Especally how the Pokemon anime is in shambles in terms of animation quality mid way though 2019 (Journeys) then just jumped ship. A pity. No wonder the community rarely posts Pokemon clips onto Sakugabooru… Read more »

I thought the anime was going to be a modern day Urasawa’s ‘Monster’adaptation where it was ‘good’ anime adaption that could have been better in service to a prestige work , but now it seems to be more akin to ‘The Wicker man’ movie (not in terms of quality) where overt and subtle changes in delivery fundamentally change the feel of the work despite the story being mostly the same.

I find it a little strange that the way the producer thinks that making the anime more accessible for a wider audience is to not let it have a unique or extreme style, I feel like that is something people want, even if they haven’t personally fallen in love with Fujimoto’s style.

The manga’s style itself has already amassed a pretty wide audience… I would think he’d want to cater to that.

Re: someone else’s comment, I’m of the opinion that more “photorealistic” animation styles have the potential to make things feel *more* unsettling and surreal, because they hew closer to the way we perceive our actual world. This is part of what I love about Ghost in the Shell (1995); with Okiura’s highly realistic character designs and restrained, weighty movement, the more bizarre and unsettling elements are brought closer to our own experiences and we are forced to confront them not (so much) as moving drawings, but more as representations of a potential reality. This “heightening” effect, the action of merging… Read more »

Sorry if my English is bad. Personally, I loved the adaptation. And when I say it, I mean it (totally, the way they made the composition is just mesmerizing). I read the part 1 of CSM 5 times and I’m sure the staff did it more times so I think they understand the key points of story and the dynamics of the fight scenes. Indeed, all the fights we had until now are pratically a basically the prologue, Denji’s fights are meant to be berserk and unixeperienced at first, when he uses the chainsaws it kinda makes sense to me… Read more »

thanks for your insight, I now understand why CSM reminds me so much of Psycho-Pass. Both ground their surreal, horror elements by contrasting them with realism, which in my experience has been a hallmark of Japanese horror (though my experience in that regard is definitely limited). Had the title run to US-style splatter fest (as the word “chainsaw” might lead people to expect), it wouldn’t be fun for me. Horror needs normalcy to really shine. Tom hitting Jerry with a big hammer is worth a smirk because it’s expected, but when CSM pulls out the big hammer it’s funny because… Read more »