Yusuke Matsuo, Do It Yourself!!, Yama no Susume, And Storytelling Through Comfortable Animation

Many anime try to offer their viewers a relaxing experience, yet few can seamlessly blend that goal with their themes and visual storytelling like these two little gems: this is the story of Do It Yourself!!, Yama no Susume, and their animation leader Yusuke Matsuo.

The Fall 2022 season of anime has brought us an exceptional crop of new titles, and perhaps most importantly, it has done so across entirely different genres—regardless of what type of show you fancy the most, this season has likely offered you something that isn’t just up your alley but also strongly put together. One of those blessed genre spaces happens to be an anime staple: shows where a group of youngsters comes together to do a hyperspecific, down-to-earth activity, bonding over it and allowing the viewer to have an entertaining, mostly relaxed time throughout uncomplicated—but not necessarily vacuous—storylines. Which is to say, what a lot of viewers have come to call Cute Girls Doing Cute Things, an amusing but not necessarily adequate term; after all, the cutest current example is Cool Doji Danshi, a series with an all-male main cast where the very specific activity that brings them together is public embarrassments and the ensuing attempts to play it cool. Although labels are flawed by design, I think that the iyashikei/healing term gets much closer to capturing the actual appeal of many of these works, even if that is only one of multiple goals for them.

Out of all shows vaguely sticking to that type of premise, Bocchi the Rock has earned to most acclaim, and there are good reasons for that. Its much stronger comedy focus gives it something for a broader audience to latch onto, especially when its humor is as sharp as it is. The protagonist’s character arc is archetypical but in consequence clearly defined, and the direction is quite good at selling it as a compelling inner conflict. And of course, the delivery as a whole is so creative to the naked eye that any viewer can tell they’re experiencing something unlike any other show out there. It’s frankly no wonder that the show has this many people completely enamored with it. You really did it Bocchi, you inadvertently became the popular girl that your shallow ego always desired.

If you look past Bocchi‘s dazzling appeal, you might encounter two fascinating sibling projects that fall more traditionally under that healing umbrella. In a different context, two concurrent TV anime sharing the same designer and leader of the animation process would be quite the worrying sign; one that would hint that they perhaps weren’t very involved in those projects, or that the schedule put unreasonable pressure on them to handle both jobs. Fortunately, the person in question happens to be Yusuke “Fugo” Matsuo, and those projects had such ample schedules that it led to comical situations; like, for example, animators commenting how weird it felt to return to the same 1 cours anime they’d already worked on 2 years prior to do some extra work. Although the overall production process for TV anime can be much longer than fans realize, rest assured in knowing that it’s not exactly common to have a rather short series animated over nearly 3 years. Given the results, though, perhaps it should be.

As helpful as it is to have a schedule that accommodates such a large workload, no amount of time alone would have conjured work as appealing as Fugo’s out of thin air. It’s public knowledge that he began forging his skills at Kyoto Animation, but even among the members of such a special studio, he was always on the extraordinary side of things. While he has admitted that he struggled to live up to his own vision and the generally high level of draftsmanship of his peers, Fugo shot up to key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. duties after his trial period without spending any recorded time on in-betweening duties. Within just a couple of years, he was already earning the praise of the likes of Yukiko Horiguchi, which was reflected in how they’d trust him with jobs as demanding as handling over a hundred cuts in an episode. Contrary to most people who work for them, Fugo’s stint at KyoAni was rather short too, taking a certain studio exodus at the time to go his own way; quite literally, because after following other ex-coworkers for a bit, he quickly made sure to tread his own path. In no time, Fugo had become the type of artist who is followed, rather than one to follow.

So, what is it exactly that to this day draws other animators to Fugo? In issue 014 of AnimeStyle, and as part of the coverage for one of his projects, Yuichiro Oguro hosted a roundtable discussion featuring younger creators who’d worked under Fugo there, many of whom have gone on to already have notable careers of their own. They all went on to praise him effusively, explaining how he’d had shifted or downright revitalized their entire careers. One such case was Kazuaki Shimada, currently occupying the position of character designer and co-chief animation director for the Spy x Family anime. Shimada—Shima-D to Fugo—explained how he’d first met him while wearing a shirt of his BLACK ROCK SHOOTER OVA in an attempt to cause a good impression on an artist whose early works he already loved, and most importantly, confessed that it was an invitation of his and the positive impressions that ensued which stopped him from literally quitting the anime industry.

When it came to highlighting Fugo’s strengths as an artist, everyone’s answers were all over the place. Some pointed at his acting finesse, others at exciting action. There was praise as specific as the tactility of his high cel work, and as general as the cuteness of his art. Mentions to qualities of the past like his usage of deliberately jumpy animation on the 4s that he once picked up from Kenichi Kutsuna, as well as still relevant virtues like his solid layout constructions. Shimada himself ended up concluding that to him, Fugo is simply capable of drawing anything. His idol’s answer denied it, but in a way that hints at the versatility that he does have; “I really can’t draw the things I haven’t drawn yet”, he said, somewhat admitting that he has more or less mastered everything he’s already tried. His technical fundamentals support that, but above everything else, it’s one thing that makes Fugo feel almighty: his eye for natural animation. Not necessarily realistic, but drawings and overall visual compositions that feel comfortable, coherent within their world, simply frictionless. In short: comfortable animation. Perfect qualities if one were to head one of those relaxing, healing cartoons.

For as consistent of a quality as that has been in his work, especially when production circumstances haven’t boycotted him, it’s worth noting that Fugo’s actual artstyle is in a constant state of shifting, even within singular projects; always recognizable, yet never quite the same. When prompted about this, Fugo explained that he’ll go as far as redrawing design sheets in between seasons of anime that don’t actually demand an update for narrative or production changes. And he’ll do so, despite it increasing his workload, because it’s important to him to draw what is most natural to him in that specific moment—something that is constantly changing. This mentality, which is the source of his greatest quality, he framed as a potential negative as well. Fugo contrasted himself to other artists who have the ability to perfectly replicate their own art forever, claiming that what the likes of Shimada do is impossible for him. With that view, it’s understandable that he decided to double down on naturality as his artistic ethos instead. After all, if he can’t force himself to follow old patterns, he’s better off taking the opposite approach and letting his pencil flow free, as that has also translated into frictionless animation in the audience’s eyes.

Much of this animation philosophy was disclosed in a long AnimeStyle feature about Yama no Susume, a series he has carried on his back for nearly a decade at this point. This season, its latest entry happened to coincide with the release of Do It Yourself!!, an original anime where he also served as the character designer and main animation director. Both of them exhibit these qualities in their own ways, though it would do them and their teams a disservice to reduce it all to Fugo’s frictionless appeal—even if that is inseparable from them in more regards than the animation alone.

Neither show is lacking in conflict and purpose, even if those are kept within the down-to-earth scope of their stories. DIY’s structure is simple and unassuming, telling a cute story about noted klutz Yua Serufu and the friendships she builds—new and old—precisely through the discovery of the joys of handcrafted creation. The message baked into that premise is not revolutionary, yet it feels more pointed than similar works, perhaps because it originates from a visionary mind whose works are often rather optimistic about the potential of technology; a series like this dropping amidst the sad rush for AI automation in art can only be considered an act of god. Without outright denying technological advance, and if anything showcasing very quirky near-future inventions, DIY makes a solid case for manmade creations as a means of individual expression, a way of bonding, and even as a community-building mechanism.

This message, which remains consistent until its ultimate conclusion, goes perfectly hand in hand with the show’s visuals. And it’s that ability to get absolutely every production department on the same page that is the most impressive aspect about DIY, what makes it click together like few shows do. As you’d want in a show with this theme, the backgrounds are painterly and also farcical, often with corners fading to white as if to underline that is something that a human being painted. The colors of those backdrops are beautiful on their own, but even more so in the harmony they achieve with the other elements in the show. DIY goes to almost unprecedented lengths in seeking internal cohesion, even in highly situational sequences. It can be a background art shadow cast by a cel layer character to increase that harmony, painted mobs to blur the lines between types of assets or full cel shots to remove them entirely, beautifully restrained digital touches, minute color design shifts, you name it—DIY is always doing its best to feel natural, with no inner friction. None between its writing and visuals, and none within the many aspects of the latter.

And as we established before, few people can nail that feeling through animation like Fugo. Like the rest of the team, he also adjusted his style to fit the theme of the series. His designs are a bit more stylized than we’ve been used to as of late, encouraging the type of looseness that evokes the spontaneous, unrestricted spirit of handicrafts. At the same time, the linework is still very well defined, which makes the switches to the very precise animated tutorials feel rather natural as well.

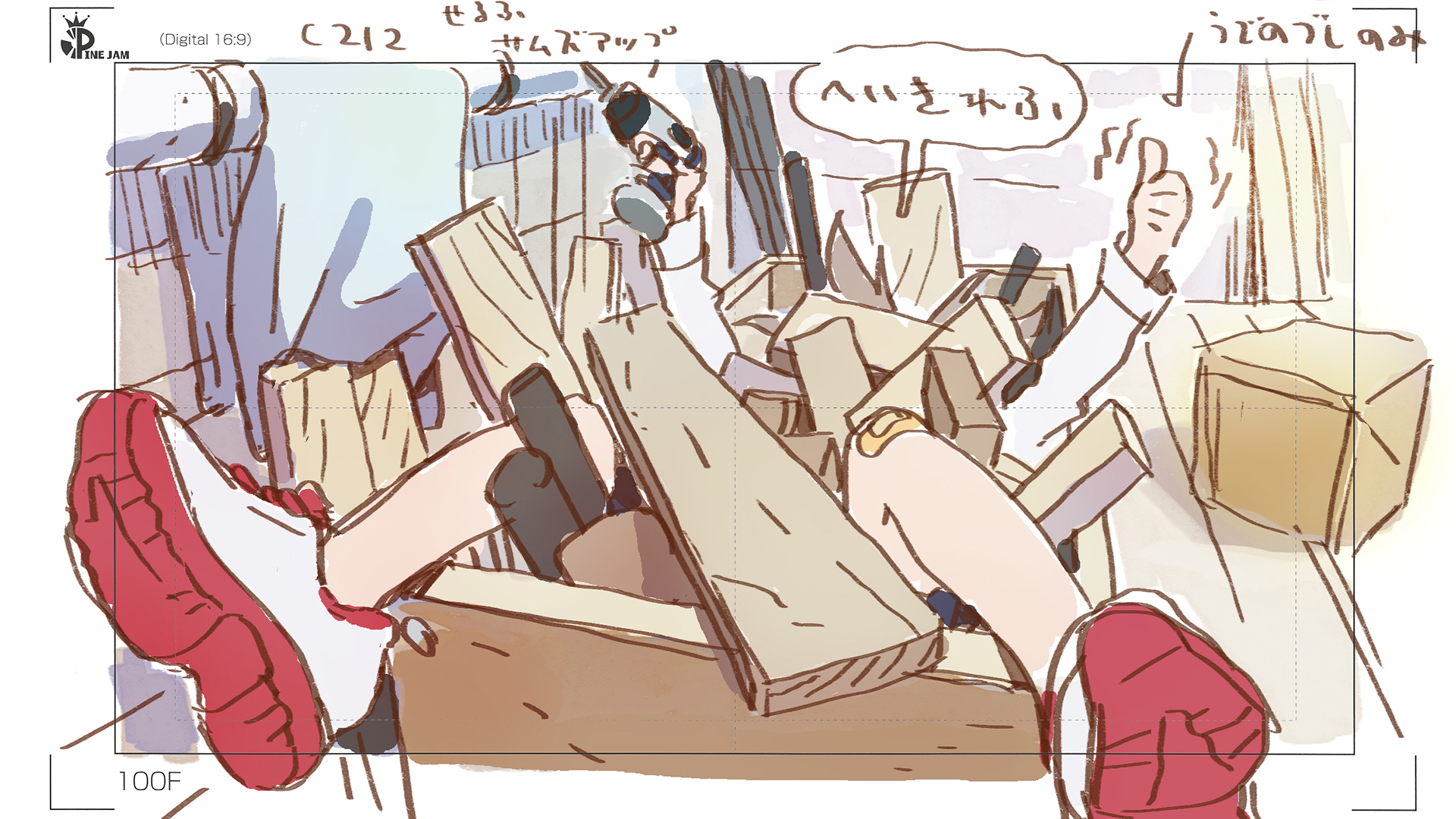

As tends to be the case with him, Fugo was so active in defining each character visually that his role became as inherently tied to the storytelling as the director, writer, and original author. Whenever he has the opportunity, he is the type of designer who’ll provide not just very rich expression sheets, but also all sorts of references for the body language of the characters. In his very thorough corrections of the first episode, he completely redrew every spaced-out Serufu mannerism, every pouting and irritated Purin. He provided similar references for every other character, such as the specific ways Takumin nervously fidgets her hands, or the way right about everyone should stand around in their shorthand, distance shot forms. Studio PINEJAM even shared some of Fugo’s concept art for the first episode, which should feel very familiar to anyone who’s watched the series as all of it made it into the show pretty much exactly as he’d envisioned it.

When everything clicks together this well, everyone on the team deserves major props, especially those who led each department. The undercover Mitsuo Iso, for coming up with the basis of this world, and writer Kazuyuki Fudeyasu for developing it. In-house art directorArt Director (美術監督, bijutsu kantoku): The person in charge of the background art for the series. They draw many artboards that once approved by the series director serve as reference for the backgrounds throughout the series. Coordination within the art department is a must – setting and color designers must work together to craft a coherent world. Yuka Okamoto and color designerColor Designer (色彩設定/色彩設計, Shikisai Settei/Shikisai Sekkei): The person establishing the show's overall palette. Episodes have their own color coordinator (色指定, Iroshitei) in charge of supervising and supplying painters with the model sheets that particular outing requires, which they might even make themselves if they're tones that weren't already defined by the color designer. Kouji Sakagami, whose work went hand in hand, as well as photographyPhotography (撮影, Satsuei): The marriage of elements produced by different departments into a finished picture, involving filtering to make it more harmonious. A name inherited from the past, when cameras were actually used during this process. director Yasuhiro Asagi for assembling the beautiful puzzle they’d prepared for him. And of course, series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario. Kazuhiro Yoneda, who not only got everyone on the same page but also pushed them to deliver some of their best work ever. If you were to single out who best embodies the production’s greatest qualities, though, Fugo manages to stand out; it doesn’t feel like a coincidence that, in a show that is otherwise thoroughly frictionless, the only episodes that feel somewhat off are a couple in the mid to latter half that got hit by prioritization woes and couldn’t afford to uphold Fugo’s ideals as much. But even with those minor issues, DIY is a beautiful example of cohesive, natural delivery, with an animation figure that embodies those as the centerpiece of the production process.

Then, what about Fugo’s other title this past season? For as standard as it may appear at first glance, it’s also quite an interesting prospect. YamaSusu is for the most part a bright series filled to the brim with love for the outdoors and mountain climbing in particular, but at the same time, it’s blunt about the dangers of that hobby. A pivotal moment in the series was its protagonist’s physically and emotionally painful failure to climb Mt Fuji, which she has only now conquered, 8 years later for the viewers at home. The interpersonal relationships it depicts also appear nice and fluffy on the surface, as the overall arc for the protagonist is to open up to others again via the confidence that climbing is giving her and the relationships that it’s nourishing. And yet, its team has always attempted to introduce a tinge of bitterness to it, to avoid turning their characters into unbelievably positive, naïve caricatures.

The third season in particular reexamined the relationship between the now timid protagonist Aoi and her outgoing childhood friend Hinata, who’d been pushing her to befriend more people ever since they met again. Most interestingly, it wasn’t the former at the core of the conflict that time, but rather the latter’s contradictory feelings, underlining the nasty but very human jealousy of a person who sees their once dependent friend grow relationships that don’t involve them.

At its best, YamaSusu’s outside adventures match their inner journeys, turning their modest climbing—and eating of good food—into the most satisfying experience. Although its overall structure is messy to say the least, as the show has continuously grown in scope in ways that were never planned at the start, YamaSusu is a very pleasant watch that knows when not to hold back its punches. With its slightly unorthodox progression and yet tremendously cathartic ending that calls back to multiple seasons prior, the latest season Next Summit can attest to all that.

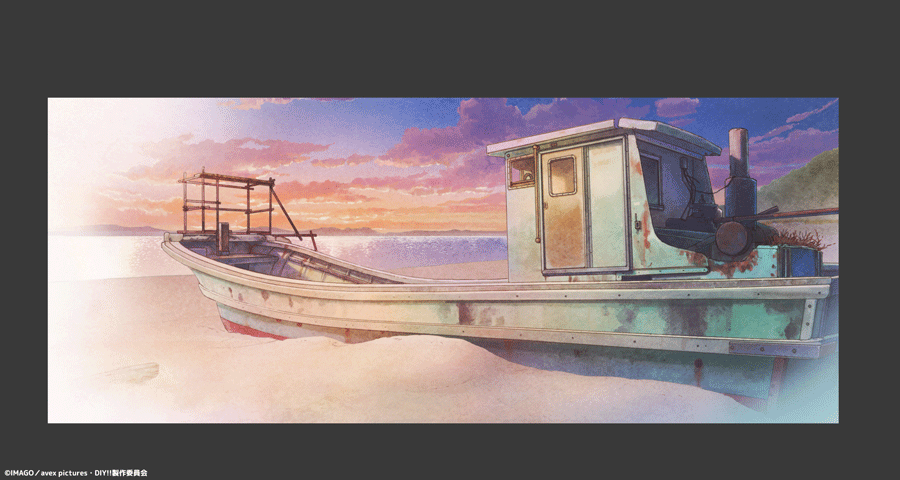

What’s interesting in the context of DIY is the way YamaSusu arrives at its default pleasant state. In contrast to its sibling handicrafts project, YamaSusu does by no means have a consistent, airtight aesthetic, and there are various reasons for that. For one, its theme is very different; while DIY got to build everything around the idea of increasing the handcrafted appeal of the visuals as that’s what the story is about, YamaSusu’s mountaineering narrative made the team… well, go climb those mountains. Over time, the inclusion of the staff’s own experiences in those locations has gained more prominence, as have the filtered photos that represent those location scouting efforts. Although by the time of the latest season these have actually become one of the main draws of the series, the road to this point has been a tricky one, marred with conflicting staff visions and uneven execution.

But what about other visual aspects, such as the animation itself? While that Fugo mantra about natural, comfortable animation rings true in YamaSusu just as much as it does in DIY, this title much more strongly represents that side of his that completely disregards stylistic consistency to achieve it. Other animation directors in the project like Noriyuki Imaoka have spoken about the idea of evoking cohesion out of a lack of thereof; if everyone’s drawings have a personality of their own, no one’s drawings stand out like a sore thumb because they have a personality of their own. This is something that Fugo himself has embodied since the start of the project, deciding to waste no time in adjusting people’s artstyles more than is strictly necessary—so barely at all in his mind—because that could stall the process and take time away from the things that really matter to him. And again, those relate to telling a story through animation in ways that don’t feel forced to the eye.

In the case of YamaSusu, Fugo’s ties to the storytelling process are even more deeply rooted than in DIY. In that same AnimeStyle issue, series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario. Yusuke Yamamoto admitted that he keeps him around the writing meetings, trusting Fugo to stop him if he ever goes overboard, and accepting his advice for aspects as fundamental as how to structure a new season. And after all, why wouldn’t he value his input this much? Although it was impossible when it came down to it, the very first YamaSusu season was planned to be singlehandedly key animated by Fugo at first, which would have made it his story as much as anyone else’s, if not more.

When it comes to executing those ideas he was already involved in establishing, Fugo has remained a very involved animation leader. At its core the ideas at play are the same as in DIY, and yet YamaSusu’s more animation-centric experience has made his role even more important. A concept that he has been obsessed with in his quest to create natural-looking animation was the control of the level of information on the screen. While certainly impactful if well used, a screen that is constantly too packed will not allow you to absorb everything, and if anything, it’ll just tense you up. To address that, Fugo has directly intervened across the entire production process. At points, he has even personally edited the location photos that serve as the basis for the layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists., so that the backgrounds themselves don’t overwhelm the viewer.

A known pet peeve of his in the same direction is the so-called enlarged animation (拡大作画); which is to say, the trend where characters who ultimately appear rather small for most of the scene are drawn larger to pack in more detail, and later reduced as needed. This increases the workload not just for the animators but also for the surrounding departments like the compositing crew, who have to tweak the lineart so that such drawings don’t clash with the rest of the shot, as reducing the size also makes the lines thinner. And above everything else, this clashes with Fugo’s desire to restrain the visual information, hence why he’s instead a strong proponent of simply abbreviating the designs in an appealing manner; something that the greatest figures in the show’s animation are onboard with, even those with otherwise very detailed styles. Rather than needlessly cram the drawings, Fugo explained, the effort should be put into the postures and body language of those lightly detailed distance models; otherwise, your dotfaced character might as well read like a scarecrow to the viewer, and that’s not ideal either.

Time and time again, Fugo’s decisions as the leader of the animation process—sometimes in a rather broad sense—have emphasized natural delivery. Through his proactive role in preproduction duties, it feels natural for the characters he helps define and for the themes of the show. Because of his attitude and approach to his own art, it’s natural coming out of his pen. And thanks to all his technical choices, it feels natural arriving to the eyes of the viewers. When the entirety of the team that surrounds him chases a single goal, it’s possible to turn that into a completely frictionless, soothing experience like Do It Yourself!!. And, even in productions that embrace a bit more chaos like Yama no Susume, his control over the visual storytelling and guidance for the rest of his very talented team makes it so that every minute action just feels right. While many anime titles fall under the umbrella of healing shows that we mentioned at the start, barely any can compare to the thoroughly pleasant experience of shows like these. That’s the power of Fugo’s comfortable animation, and somehow, this season has let us experience it twice.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

I didnt know both of my favourite anime of this season was handled by the same person! Thank you!