Kimi no Iro / The Colors Within: A Polychrome Prayer For Art [Annecy 2024]

Naoko Yamada’s recent film draws from its relationship with nature, art and the creative process, spiritual imagery, and very specific choices of instruments for its teenage band—all of them, becoming the director’s tools to express her thesis.

Guest piece by Jade. You can find her being an adventurous librarian somewhere in France.

Naoko Yamada’s The Colors Within premiered last week at the Annecy Festival, receiving a standing ovation and much praise from the audience. Those who loved her previous films were won over again, and those who did not still recognized its impeccable direction. It is similar in spirit to Liz and the Blue Bird (2018), with a much warmer tone and aesthetic, plus a more experimental structure which might surprise some.

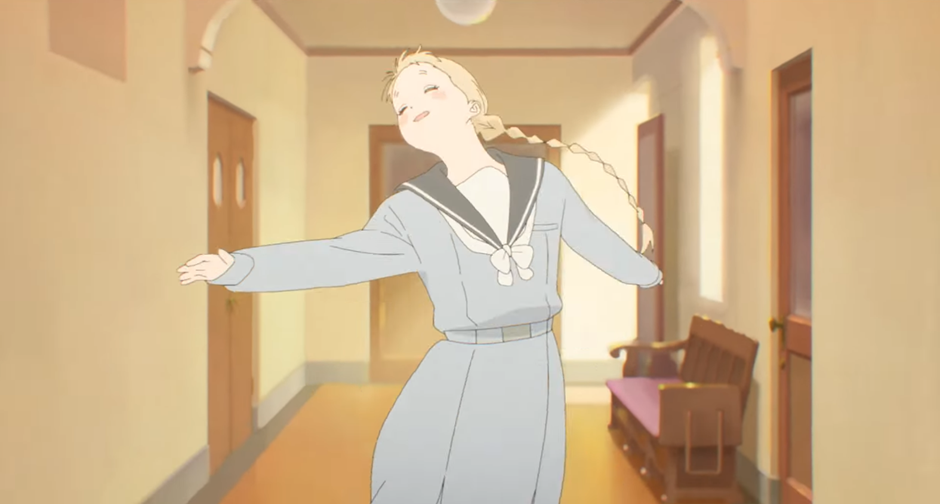

Like Liz and Yamada’s previous films, Colors Within is characterized by great attention to detail and a complete understanding of human movement, small and big: each character walks and acts in a specific way, from the school girl side-stepping her way into school to another’s anxious hand wringing. Yamada’s keen understanding of people and the way they act is at full display here. Perhaps this mastery of movements is at its peak in the ballet scenes beginning and ending the film, faithfully reproducing the difficult choreography of Giselle’s first act and then modifying it to fit the protagonist’s skills, showing all the energy and hesitation of an ex-ballet student who has not quite mastered the most difficult moves.

Besides her expected charactefulness, the film is also bursting with Yamada’s usual love of the flora and fauna. In the world of Colors Within, seasons and feelings are indicated by the brief appearance of a specific plant (like a sweet osmanthus for Autumn) or birds flying in unison over the uncharted sea—even the stickers on a character’s desk feature birds in a loving union. These illustrative moments and the way they are edited are here to both create breathing space and to symbolize emotions without any dialogue; a Newton’s cradle which reflects a character’s doubtful face shifts into unripen tomatoes, and the flakes of a snow globe intended for a loved one turn into imagined pieces of the rainbow, filling the frame with the idea of first love. The film is never overbearing with its symbols, lulling the viewer through a feather-light touch. No choice, from the music to the animation, is left to chance, yet the result seems startlingly simple.

Reviewing Colors Within without spoilers is no easy task, but talking about spoilers here also feels inaccurate, as the film has no twists and very little to no conflict. Not that the three main characters are not conflicted themselves, or don’t go through a story of self-discovery. What Yamada and Reiko Yoshida did with this film was to strip away all the usual foes and dramatic threads of a coming-of-age story. While most films spend time on tension and pathos to end in a burst of happiness and resolution, Colors Within almost does the opposite, like a continuous healing balm.

The story, which takes place in an almost fairy tale setting, perhaps a mix of Japan and the city of Annecy itself, features Totsuko, an ever-cheerful synesthete who perceives people as colors. Like a planet to the sun, she’s attracted to her fellow schoolmate Kimi, an exemplary student who suddenly drops out of school. In her quest to find her, she meets Rui, a music aficionado destined to become the nearby island’s next and only doctor. The three of them instantly decide to form a band and over a year become great friends. Like most teenagers, the three struggle with how they are perceived and how they see themselves. Totsuko cannot explain to others her unique synesthesia for fear of being rejected, Kimi cannot reconcile the perfect image her grandmother has of her with her own vague ambitions, and Rui fears unveiling a part of himself to his mother who sees him as the future savior of the island’s clinic. The core of the film is simple: acceptance and self-love.

While such themes have been tackled plenty of times before, the execution is what makes Colors Within unique. As stated, the film is painstakingly detailed, every frame jam-packed with information without ever becoming overwhelming. It is not just set in a generic catholic school, with a few biblical mentions as backdrop: Hiyoko the nun quotes both Niehbur’s serenity prayer and Isaiah 43:4 at key moments in the film, clenches her prayer beads in a moment of doubt. The choir sings popular Christian songs What a Friend we Have in Jesus and Ave Maria de Lourdes, the young ballet trainees practice on My favorite things from the musical The Sound of Music, one of the most popular if not the most popular film to watch in catholic families.

Digging further into the setting, you might notice that the students bear the symbol of ichthys, known as Jesus Fish. Totsuko herself repeatedly finds joy in confessing and praying in the chapel. The band practices in an abandoned church which shelters their instruments and friendship, and finally express themselves during the Saint Valentine Festival concert. All these elements gracefully accompany a vision of friendship, love, and forgiveness, ending on a stained-glass window that bears the words “Love Thy Neighbor”. The film is not about Catholicism or even religion: the immense research that went into creating this world simply serves as reinforcement for the thesis of the film in the best way possible.

That thesis, or at the very least the precepts that inform it, is stated in Niehbur’s serenity prayer about acceptance quoted at the very beginning. Then, how does one accept themselves? Yamada’s answer is to do it through art itself.

Art, by making the invisible visible, allows people to find love and self-love through the process of creation. The main character’s gift is directly linked to that idea. Totsuko does not simply assign random colors to people she sees, but actually perceives their hidden potential. It is what draws her to Kimi and Rui, unsure about themselves and where they will go. It is what draws her to Hiyoko the nun, a stern woman with gray eyes and a gray uniform who shines in her eyes like the morning sun. Her love, joy, and honesty help each of them to realize their worth, and thanks to music, to art, they are able to show their true self to the world.

Hiyoko, through a catholic lens, stresses the importance of creating, of expressing “truth and goodness” with what she calls hymns, which include not only joyful singing but also Kimi’s sorrowful ballad. Totsuko states that she wants to transpose Kimi’s beautiful blue color into sound, and sees her aura when hearing specific notes. The characters bond over listening to each other’s music and are energized by communal creation: not only is it necessary to create to be fulfilled, it is also crucial to share that creative process with others.

Perhaps the best example of this idea is in Rui’s instrument of choice. He plays the theremin, a direct symbol of making the invisible visible. An electronic musical instrument invented in the 1920s, the theremin is complex to master and produces an almost alien, eerie sound, akin to a humming voice. I happen to be a fan of one particular theremin player, musician Grégoire Blanc, and immediately recognized him in Rui’s hand gestures and controlled sounds.

I would argue Blanc is perhaps the best theremin player in the world today and a master of many other instruments, electronic or otherwise, arranging them in beautifully directed videos. Yamada seemed to think likewise when I met her, being a fan herself and telling me she would have picked no one else for the film. Rui’s height, his love for electronic instruments and arrangements, and even the fact that he plays in a church seemed to have been inspired by Blanc himself, who was invited to Japan during the film production to be used as a reference. Within the film, he delivers a beautiful theremin version of Adolphe Adam’s Giselle, which finally allows Totsuko to dance freely and without shame. Liz was already remarkable in its attention to music and how the beats followed the characters’ very steps, and this movie ties that into the narrative itself in stunning fashion. Kensuke Ushio‘s work is even more important here, and it is refreshing to watch animation and music work in tandem when the role of composers has often been devalued these past years—sometimes relegated to another promotional hook.

The songs they play also suit each character to a T. Totsuko’s joy and love of all things spinning is rendered into a perfect earworm about planets, which makes her and nun Hiyoko spin in another reference to Maria in The Sound of Music. Kimi wishes “to bloom like a flower”, and states that “tomorrow will always come” in a ballad and an electronic rock song, while Rui dazzles with his sensitive theremin.

Once again the devil is in the details, from Kimi’s Rickenbacker guitar to Totsuko’s Casio SA-46 and Rui’s Moog theremin. The film doesn’t bother too much with realistic instrument playing aside from the theremin, but these details as to what each instrument represents show nothing has been left to randomness. Like the catholic setting and the fairy tale place in which the film takes place, there is a blend of realism and idealism that makes the film’s spirit so contagious. It’s the exact type movie that makes you want to leave your house and start a band immediately.

In the end, then, what are the colors within this highly encouraging film?

The three characters in the film are represented by the additive colors of Red, Blue, and Green. Thanks to various props and clothes, their parental figures are themselves depicted as subtractive colors: Magenta, Cyan, and Yellow.

These colors are displayed everywhere in the film, even in the foundation of the chapel we see in the intro, before even meeting the characters: Blue (Kimi) and Pink (Totsuko) are glass frames in the chapel’s windows, while its pillars are painted a gentle sage green (Rui). Blue, first depicted as a fish swimming freely, is of course the color of Virgin Mary and a summer sky, but also of sorrow and the changing sea. This fits Kimi perfectly, as a once popular icon who decided to find her own path and struggled along the way.

Green has many meanings, but in this film it mostly symbolizes nurture, protection, and healing: even when Rui is absent his color is all over the school, in its walls, its uniforms, and of course the trees and plants. When Totsuko meets him, he’s bathed in it, and he’s almost always framed with this color in mind. Pink and red represent love, symbolized in an apple Totsuko eats every day. She herself doesn’t know of her own color, despite outright claiming she wants to be pink as a child, ignorant of her potential. The fact that it is her color is no mystery, from her pink eyes to her wardrobe. Totsuko as the incarnation of love is not meant to be subtle, but the movie avoids the cliché of the eternal angelic airhead: she’s incredibly funny and silly but has common dreams and doubts. She feels joy as intensely as she feels sadness: when Kimi abruptly leaves, her world literally stops spinning and loses all its colors.

Although the palette choices are evident, Yamada refuses the boring choice of a simple 1:1 color theory of the film. The trio is not the Powerpuff Girls: many props explicitly don’t match the theme, and the characters swap colors easily. Rui flamboyantly does not wear green at the end concert, but an Oscar Wilde lavender suit with a frilly shirt and high-heeled white boots. Kimi abandons her blue uniform to wear mostly boyish black, white, and red throughout the film, and claims the color again for the end concert with a denim vest. This keeps the film from being too cartoony and simple: the mastery of Colors Within lies in blending all this extensive research and a myriad of details into a cohesive, smooth experience. I’m certain the film will be analyzed and theorized in its totality once it is released, but it is first a spectacle for the senses, getting better with each rewatch.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!