Look Back: An Exceptional Production To Embrace The Paradox Of The Artist [Annecy 2024]

Tatsuki Fujimoto’s Look Back presents the creative process as inherently isolating and frustrating, yet inevitable and a means of connection. Now, its stunning film engages with those ideas through Kiyotaka Oshiyama’s exceptional production methods.

We classify gold according to its purity, most often expressed through Karats; a unit of fineness that contrasts the presence of the desired metal to its total weight, including impurities and alloys. While this does not imply that the purer the gold the objectively better it is—the increasingly higher softness doesn’t make it as appropriate for many use cases—we still consider that this quality makes it inherently more valuable. Even in situations where there isn’t such a material aspect as with a precious metal, that sentiment is common: we tend to seek the real deal, the uncompromised state.

Applying that angle to commercial art, however, is tricky. While independent works may be allowed to truly be themselves, the sheer size that commercial teams grow to (especially when poorly planned, which is also a common occurrence in these environments) inevitably introduce extraneous particles. Add to that external pressures like those by the producers, and you have a situation where it’s impossible not to contaminate that ideal in the mind of the project leader. Much like in the case of alloys, that mixing isn’t inherently negative; many of anime’s greatest achievements can be traced back to dynamics born of collaboration, which would have never popped up in the director’s mind regardless of how brilliant they may be. And yet, despite being effectively impossible and not necessarily superior, we still find ourselves seeking more of that purity. We want it as viewers, and so do creators.

One such artist is Kiyotaka Oshiyama. Mind you, we’re not talking about a rebel who fundamentally rejects organized animation production. Oshiyama has been in the anime industry for 20 years, and ever since he broke out with his animation directionAnimation Direction (作画監督, sakuga kantoku): The artists supervising the quality and consistency of the animation itself. They might correct cuts that deviate from the designs too much if they see it fit, but their job is mostly to ensure the motion is up to par while not looking too rough. Plenty of specialized Animation Direction roles exist – mecha, effects, creatures, all focused in one particular recurring element. debut across Dennou Coil, he has been a very sought-after individual. Regardless of his high technical skill, or even his exceptional versatility and speed, no one who doesn’t click well into collective working environments would be invited to as many prestige efforts as him. He’s respected as a creator and appreciated individually to a degree that confirms this reading.

And yet, it’s undeniable that he’s drifting in a very individual direction. The first major hint came a decade ago with the release of Space Dandy; most specifically, with the nearly-solo effort that became the 18th episode. Though Oshiyama contributed to the series in multiple occasions, personally key animating no less than 50 cuts alongside other superstars in episode #22, it was #18 that was constructed in a fundamentally different way. He wrote its script, storyboarded the episode, directed it, provided designs, drew all the key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. (with limited clean-up help), supervised every cut, and at points drew some in-betweensIn-betweens (動画, douga): Essentially filling the gaps left by the key animators and completing the animation. The genga is traced and fully cleaned up if it hadn't been, then the missing frames are drawn following the notes for timing and spacing. as well. Within a project that encouraged artists to imagine a world of their own, he committed to that approach to a degree no one else was able to.

Just a few years later, on his directorial debut with Flip Flappers, he found himself on each of those roles again despite his responsibilities increasing by an order of magnitude—not enough to stop him from also doing some voice acting and playing the didgeridoo, seemingly. It was that ability to be the most effective figure in the trenches even as a leader that bailed the production’s collapsing schedule, with Oshiyama and character designer Takashi Kojima handling an impossibly large number of cuts despite their positions. And gradually, this ability to handle such an unconventional workload became a desire to do so.

In a fascinating interview about the production of his new film for Animage 553, Oshiyama explains that after all these years of creating animation within large groups of people, he started getting tired of that. His points of frustration with that system are common ones, even among individuals who don’t later try to reformulate the approach to producing animation; as an artist, it’s not the most pleasant of feelings to see that your work has morphed beyond recognition when it makes it to the screen, be it for deliberate artistic disagreements or due to anime’s messy inner workings. The first point you can more easily dodge by climbing up the ladder, but there is essentially no way to becoming impervious to the risk of passing on a workload to others. The solution to that is as simple as it is unattainable for most: just do it all yourself.

It was that mindset that led to the founding of Studio Durian alongside his partner Yuki Nagano, who had precisely been the production desk at studio BONES for Oshiyama’s outstanding episode of Space Dandy. To support their rather idealistic intent of creating uncompromised animation without the interference of industry norms on any level, the two came up with multiple schemes. Those ranged from spreading Oshiyama’s name further through his now common roles as a designer in high-profile anime, to much more unique ones, like his personal atelier offering art corrections as means of guidance for artists. If there’s one way to prove the capacity of your unconventional studio, though, it’s to create something exceptional through the methods you’ve committed to. And that is precisely the role of the 2019 pilot film for Shishigari, a stunning representation of the theme of man vs nature through Oshiyama’s stylized, round, yet tremendously visceral animation.

Whether he eventually gets to produce a Shishigari feature film or not—we should all wish that he does—Durian’s efforts did pay off. In the aforementioned interview, Oshiyama reveals that an Avex representative approached him to pitch the production of a Look Back film, though he would have to participate in an audition with a pilot to earn that position. For an individual so committed to his views, Oshiyama has also spent the last few years pondering if his radically different take on Tatsuki Fujimoto’s work would be well received. Chances are that he has had that worry since the very start, as his comments point to having spoken with Fujimoto once he had already secured the spot in early 2022; which is to say, that he’d have participated in the audition around the release of the lavish pre-animated PV for the Chainsawman TV show. As it turns out, his worries were for naught: he did indeed secure this title, and the public reception so far has been exceptionally positive.

It barely takes a few seconds into the film to realize why the director thought the style might have been contentious, but also to understand why it has left such a strong—and so far positive—impression. Oshiyama’s view of Fujimoto’s art is one we’ve echoed before on this site: much like his storytelling, his drawings feel very spontaneous and of the moment, which ought to give the animation a similarly organic feel. As if to combat the inherently more clinical feeling of digital animation, various teams have been employing different strategies to give a rougher look to the linework; be it the classic emphasis of unconnected lines or filtering processes that deliberately damage them. By approaching the idea of that angle, however, you’re further diluting the hand of the original artist—precisely the type of consequence that Oshiyama takes issue with.

Instead, and right upon the public announcement of this work, word came from their team about their attempts to convey the lines of the key animators exactly as they were. In Oshiyama’s view (and many others), the traditional process of tracing their art for inbetweening purposes tends to lead to a loss of nuance; and, with the industry further fragmenting each step of the animation process, those losses of intent and personality pile up. What was once bearable because of the smaller teams is now a constant blurring of the initial vision. Through a nearly direct presentation of the original artist’s lines and by deliberately limiting the number of animators—which meant drawing half of the key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. for the film himself and leaving the rest up to very skillful individuals—Oshiyama is challenging all the industry trends he found bothersome and unfulfilling.

While those ideas are interesting on their own, it’s in their intersection with Look Back’s own worldview that they make this a fascinating adaptation. Even on a stylistic level, Oshiyama attempted to meet it beyond its superficial traits. Saying that the film has a rough look to it to mimic Fujimoto’s spontaneous pen isn’t wrong by any means, but it misses how much further the director went to engage with its core. So, let’s dig deeper into Look Back just like his team did.

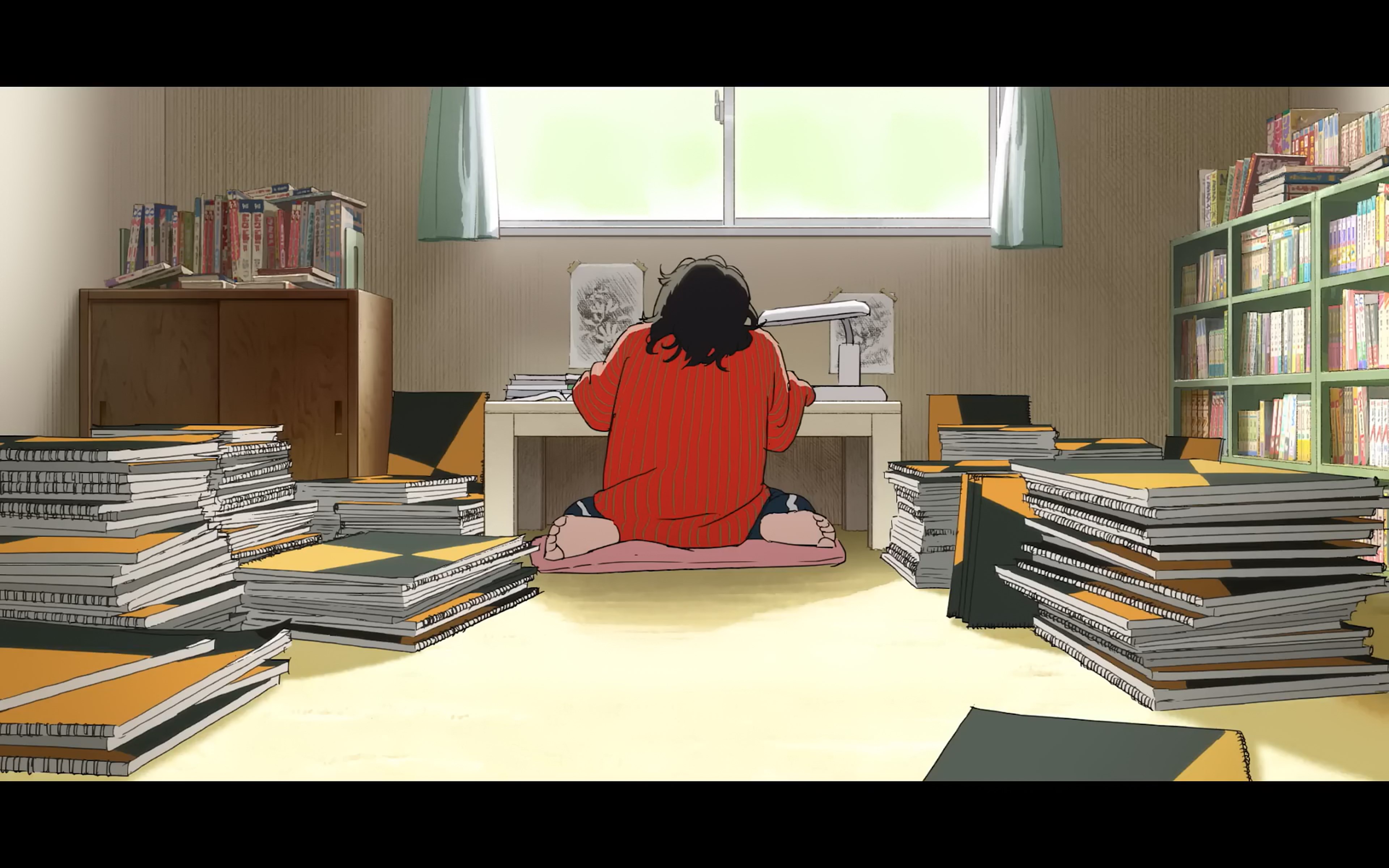

Though its short length makes Look Back less susceptible to it, Oshiyama considered the more organic nature of manga, where the artstyle naturally shifts across their run in a more accentuated way than in anime. By being a work about that medium, however, he saw it fit to recreate that effect… by putting together character sheets for others and then never looking at them himself, drawing characters as it felt natural each day, for every stage of the production process, and according to the work’s (and his) current mood. By personally handling so many scenes—not only as the key animator of half the film but also as its sole animation director—his presence would be the cohesive factor in the way the mangaka’s touch is, but without the drawbacks of a regular Chief Animation DirectorChief Animation Director (総作画監督, Sou Sakuga Kantoku): Often an overall credit that tends to be in the hands of the character designer, though as of late messy projects with multiple Chief ADs have increased in number; moreso than the regular animation directors, their job is to ensure the characters look like they're supposed to. Consistency is their goal, which they will enforce as much as they want (and can)..

When combined with his workaholic personality, this has led to a situation where Oshiyama has been redoing already finished shots because past styles no longer felt quite right, sort of getting stuck in a loop of retakes that has made the production cut it way closer than it would have been under normal circumstances. Mind you, that aspect isn’t ideal on all levels; although the labor dynamic is entirely different when we’re talking about a company’s founder subjecting himself to 2.5 months of living in the studio than it is with anime’s regular exploitation, the implied celebration of that in promotional events is still an icky cultural issue. When it comes to the finished work, however, he absolutely achieved his goal: Look Back feels alive in the way he sees Fujimoto, and how he envisions manga as a whole to be.

Beyond this interaction between Oshiyama’s methods of expression and the format that the story also happens to be about, it’s the narrative itself that also holds a conversation with the delivery and production methods. For those who have yet to read Look Back, it’s Fujimoto’s raw, somewhat biographical tale about the inescapable desire to draw manga. It begins by following the young Fujino, a vain elementary schooler whose sense of humor and advanced drawing skills for her age have earned her acclaim by those around her—something that fuels her desire to draw. Even at the start, and coated with that narcissistic mindset, drawing is seen as something you do for others as much as for yourself.

Upon meeting the recluse Kyomoto and her much more impressive technical skills, however, Fujino’s reality is shaken up. Oshiyama’s original additions to the framing of the story capture her character better than before; once just a 4 panel strip within the first pages of the comic, Fujino’s drawings are animated into a full lavish scene, yet preserving their very childish charm. When her classmates are exposed to Kyomoto’s ability and immediately place it over Fujino’s, the camera begins to pan away until she’s just a small dot sitting in a classroom with hundreds upon hundreds of students; a breach of reality to showcase just how insignificant Fujino feels now that her special trait is no longer propping her up. Similarly, the very characteristic running forms that are suggested by Fujimoto’s artwork as an amusing escape valve for her emotions—whether it’s fury that she lost that position or joy when she finds out her enemy is in fact a big fan of hers—are expanded into very involved, unforgettable dashes.

Neat as those additions are, it’s the intertwining of Look Back’s message and the movie’s craft that resonates the strongest. Fujino and Kyomoto are quick to become not just friends but partners, finding success in a world of manga at an exceptionally young age. Warm and pleasant colors bleed out into the screen, flexing color design muscles that are also indispensable to getting away with the fairly flat rendering of the character art. Even as their career sees nothing but success, however, they cannot escape the inherent friction of trying to create art collectively.

Kyomoto, who had been handling the backgrounds in their works, cannot help but step down from her position to seek improvement in her art—much to the displeasure of Fujino, awkward as she is to convey that. When that choice leads to tragedy, the protagonist can’t help but feel like it was her fault, as the one who dragged out a shy recluse to embark on a manga adventure with her.

And yet, a multidimensional detour makes its point: Kyomoto would have eventually made that choice regardless, because the creative process is inevitable for those who are afflicted with that chronic illness of the soul. Oshiyama’s storyboards had effectively already made that point before; even as she hesitates on whether to continue pursuing art when she faces adversity at a young age, manga is all that Fujino’s eyes ever reflect, so of course that would be the same for Kyomoto. The film embraces the paradoxes of creating art as a path that is taxing on your body and social standing, but also uniquely fulfilling at points, and inescapable if you’re destined for it anyway. Of making something together as particularly joyful, and yet, of the tendency to isolate yourself when you do. Just like Fujino, many artists never stop creating because they expect something from others; but with a bit of luck, that other figure and their reward become more meaningful than classmates briefly thinking you’re cool.

In a brief addition, an already serialized mangaka Fujino speaks to someone who is presumably her editor. In the professional tone that is expected of her, she essentially says that her assistants are more of a problem than they’re worth. This serves as a beautiful character note—she simply misses Kyomoto—but also feel particularly meaningful with a movie so clearly led by an individual like Oshiyama. He too has felt the joy of making stuff alongside other people; even for this film with the balance extraordinarily tipped in his direction, he has effusively thanked every other member of the team. And yet, he gets it better than anyone that there is a craving and even a tendency to want put yourself out there in an uncompromised way.

Look Back is an excellent film that feels even tighter than Fujimoto’s one-shot already was, with the very way it was animated reinforcing many of its central ideas. It’s a true luxury to have one of his shorter works receive such a unique, thoughtful treatment. It would be nice to see something similar happen for other one-shots, wouldn’t it?

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

Thank you for this! I’m now looking forward to see the movie more and wanting to experience Look Back with Oshiyama’s vision and all of his team’s hardwork!