Kimi no Iro / The Colors Within: Naoko Yamada’s Love Spins Round and Round [Annecy 2024]

Naoko Yamada’s new film Kimi no Iro / The Colors Within is gorgeous, highly entertaining on the surface, but as densely packed as ever. Through colors, light, faith, spinning, and gravitation, it formulates the director’s kindest message of acceptance.

When she was conceptualizing her first film around 14 years ago, Naoko Yamada’s surreal pitch was to spend an hour and a half following K-ON!’s protagonist Yui as she attempted to thread a needle. After all this time, I’m happy to announce that she hasn’t only matched the level of non-conflict in that proposal, but gone even further in her denial of a traditionally fulfilling narrative. While Yamada always thrives in personal, down-to-earth character stories, there is a dramatic edge in the likes of A Silent Voice or Liz and the Blue Bird that is deliberately missing from Kimi no Iro / The Colors Within. Mind you, this is not because it lacks somber feelings or situations that could lead to heavy negative outcomes—but rather, due to its thorough commitment to a message of acceptance and understanding, towards others and to ourselves.

No one embodies that spirit better than its protagonist Totsuko, who precisely opens up the film by reciting a prayer that preaches acceptance of the inevitable, courage to tackle that which can still be addressed, and wisdom to tell the two apart. As the film’s reveal already underlined, she has a case of synesthesia that allows her to perceive people’s auras as if they were colors; not quite on a purely visual level, since it’s something that she feels in a more profound, all-encompassing way. This immediately offers the narrative room for dramatic conflict: flashbacks to a young Totsuko, incapable of understanding that her vision of the world doesn’t align with that of the majority, is strikingly isolated through Yamada’s storyboards.

As it becomes obvious throughout its runtime, however, the movie declines to pursue this direction too aggressively. A slightly numbing sense of loneliness rings throughout the whole film, still drawing lines between the protagonist and her surroundings. The architecture of her room often separates Totsuko from the lovely roommates she can’t be fully honest with, but never makes a grand, dramatic point out of it. The Colors Within presents a world fraught with lies and uncomfortable feelings about not belonging, yet so firm in its belief in the goodwill of people that there’s never an issue to solve a problem when it’s approached with honesty.

To embody this whole worldview, the movie is firmly rooted in the Christian school that Totsuko attends; as Yamada herself commented for Variety, this isn’t so much to make a movie about Catholicism, but to use a very kind reading of its precepts to sustain those ideas, and to have a place that holds people with different beliefs in the first place. And indeed, as the director noted in her research, the protagonist is actually seen as a bit of an oddity in school for her devout behavior. That understated sense of friction in a clearly well-meaning world is our starting point in this film.

Before you’ve got any chance to grasp the movie’s philosophy, the synesthetic direction immediately jumps out as an excellent fit—both for the character and the individual leading the project. Yamada is well known for her ability to abstract feelings into a wide audiovisual language, which she then contrasts with her cute yet naturalistic approach to character animation. Her evolution as a theatrical director in particular has noticeably emphasized this aspect. A Silent Voice’s Japanese title The Shape of Voice has an inherently synesthetic spin to it, something that her execution made a point to highlight. Much of Liz and the Blue Bird hinges on extrapolating interpersonal relationships into forms that can be physically felt like the BPM of their shared footsteps, and the director’s relationship with composer Kensuke Ushio only tips the balance further in that sensory crossover direction; look no further than its soundtrack, partly created through a process of decalcomania that binds color and sound. To anyone following her career, a synesthetic protagonist ought to be the least surprising development.

When it comes to the character herself, the condition immediately clicks into place as well. To put it simply, Totsuko engages with life so fully and intensely that it’s natural to buy into the idea that she perceives it on a whole additional level. Her joyful body language embodies that mindset, as does her unshakable faith. Without being an abrasive nor particularly loud person, you can count on her to be thoroughly committed to whatever she happens to be doing; even if that happens to be spouting lies for the sake of a friend, in which case she will spectacularly do so, like it’s the most natural thing in the world. A child who doesn’t simply get carsick, but visibly, comically dizzy upon the mere mention of a vehicle. That is Totsuko, a protagonist whose synesthesia feels like a direct extension of her way of engaging with the world—and also one whose goofy hijinks make this Yamada’s most easily digestible, funniest film since K-ON!.

Right as she explains her ability at the beginning of the film, Totsuko ponders about the one color she can’t perceive: her very own. Rather than a mystery for the viewer, this question is posed as a vehicle for self-discovery and once again, acceptance as well. After all, the movie’s official poster already spells out the colors that dye its main characters, just like Totsuko herself inadvertently does in that same scene; when talking about the way a normal person’s eyes perceive the world, she exemplifies it with a red apple, a green tree, and a blue fish—the colors that are quickly assigned to the main cast. Reds, pinks, and generally warm colors always follow Totsuko in a way that befits the character, to a degree that no viewer will ever feel like that is a puzzle for them to solve. However, since she has yet to fully come to terms with her unique nature and standing, white colors embodying that lack of self-understanding also play a role in her life. Still within the introduction, that point is elegantly made by a young Totsuko attaching a white sticker on her face as she wonders about her own color.

In another direct extension of her curious, proactive personality, Totsuko isn’t content with simply perceiving people’s colors: she craves the beautiful hues emitted by others. Yamada’s penchant for floriography takes a slightly different angle as Totsuko compares herself to a bee that pollinates alluring flowers, explaining how she naturally gravitates towards people with those attractive auras. That exact imagery is invoked again when she purposefully stalls in the school hallway, just to witness the next member of the main trio.

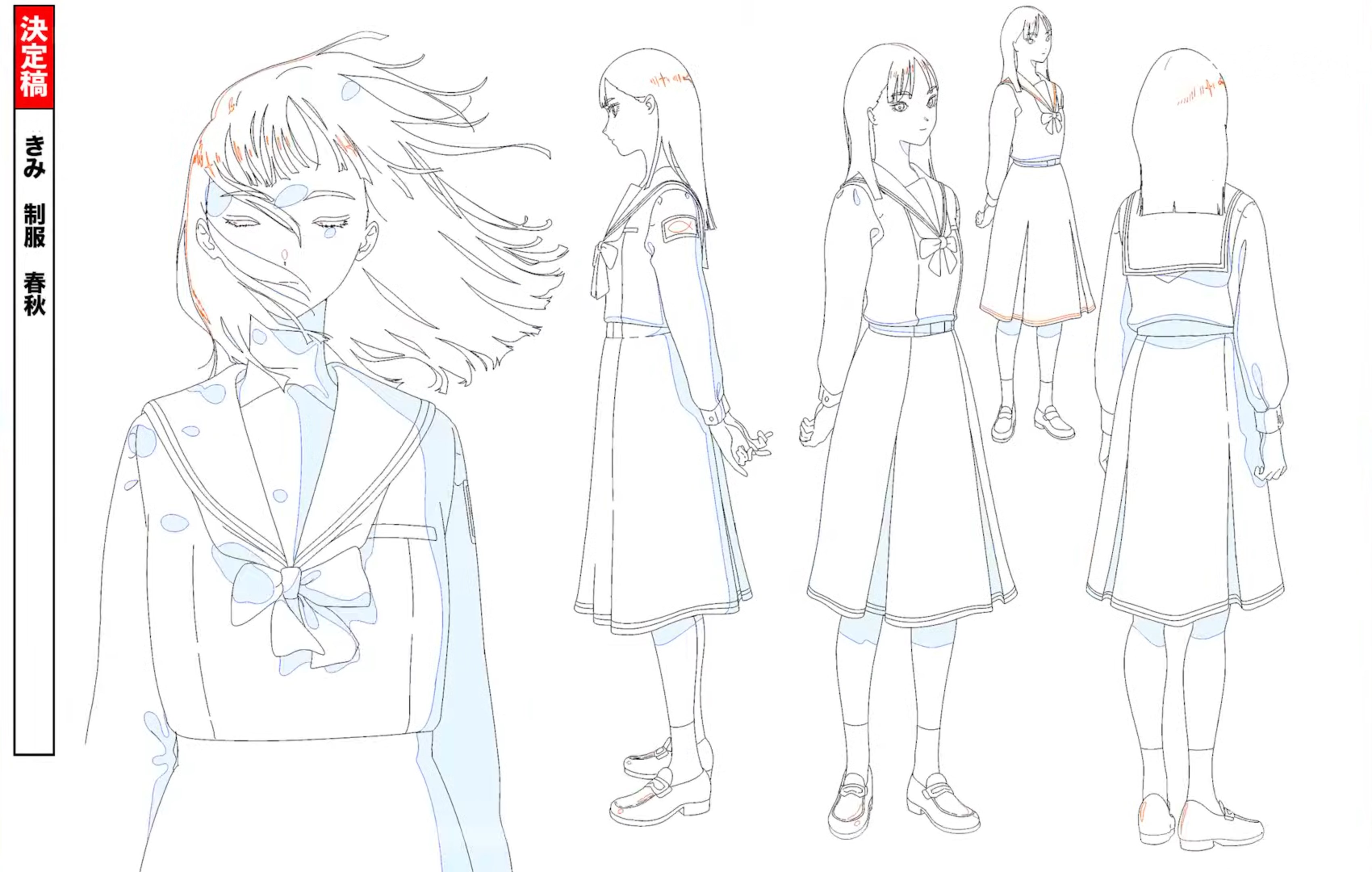

Kimi appears to be a model student, though it quickly becomes clear that the gorgeous blue that Totsuko perceives runs a wider gamut. She’s a highly respected individual and member of the school choir, though what the protagonist appreciates is clearly something more pure than those achievements, a serene blue inherent to her own being. While always dazzling to Totsuko’s eyes, we see those azures become duller when, seemingly out of nowhere, Kimi drops out of school—an event that drains the color out of Totsuko’s life as well. Again, this is an event the film refuses to sensationalize; we never even see her drop out, nor is the reason directly alluded to beyond the feeling that she felt friction with the expectations placed on her. Instead, we see her carefully take off the school’s uniform in one of the most thorough pieces of animation in the entire film. After that point, Kimi is never truthfully seen as a student again.

Her actions immediately afterward set the course for the whole film. Kimi proceeds to pick up the guitar, a new hobby she has been practicing while working part-time at a library. When hearing rumors about this, Totsuko embarks on the adventure that gathers the main characters together—and their colors along the way. From the still muted blues in Kimi’s morning routine and the reddish afternoon as Totsuko gets sidetracked by a cat, we move onto the soothing greens of Rui; the color that adorns the second-hand piano we see him buying, in a street decorated with similar hues.

Much like Kimi, Rui also finds himself in an uncomfortable position with regard to the expectations placed on him. Across an understated narrative thread, we find out that he heeds from the one family of doctors on a somewhat remote island, the type where it feels like you’ve slid a couple of decades back just by setting foot there. Family photos hint that the heir of that position would have normally been an older sibling who is never mentioned across the film; with him presumably off to chase a different dream, he feels the pressure to follow this path.

Although he’s still willing to live up to those expectations, Rui seeks an escape valve in the form of the actual passion that he keeps hidden: music, and a whole sensitive side that might hold more meaning about his real self. His path finally crosses with the rest of the gang at the White Cat Hat library, where Kimi works and practices, inhabited by the same feline that Totsuko was chasing. That color also happens to be the additive result of their three colors, so it’s only appropriate that the name of their band—which is formed on the spot, thanks to Totsuko’s shameless behavior—is owed to that same cat. The film’s prism is finally complete.

Beautiful in its own right, the palette becomes as important to the storytelling as the movie’s title implies. It’s no surprise that Yamada decided to rely on color designerColor Designer (色彩設定/色彩設計, Shikisai Settei/Shikisai Sekkei): The person establishing the show's overall palette. Episodes have their own color coordinator (色指定, Iroshitei) in charge of supervising and supplying painters with the model sheets that particular outing requires, which they might even make themselves if they're tones that weren't already defined by the color designer. Yuko Kobari: a reliable comrade of directors with a keen eye for color like Skip & Loafer’s Kotomi Deai, and someone whose formation in the cel era of animation grants her a more material understanding of color in a movie that is all about mixing them. Even when it’s not presenting a jaw-dropping abstraction of the relationships into morphing masses of color, the tones that represent everyone’s essence are present anytime the band does something. Leading to their first practice together, a now much more cheerful Kimi is set against the intense blues of the sea and the sky. When they get to Rui’s island, its intense greenery greets them; the same one that always gives him a backlit green aura whenever they play inside his secret base. Not by chance, that place is an abandoned church, which matches Totsuko’s devout character and her warm colors. After practice, as they casually grow closer, they all share different flavors of ice cream—red, green, and blue ones.

These growing relationships continue to be expressed through colors, in a way that binds the three of them even when they’re not all present. In an adorable moment of truancy, Totsuko and Kimi paint their nails to the beat of Ushio’s music, doing so not just in the latter’s color but also in a green reminiscent of Rui. As they begin making music together, the software itself labels their respective tracks in their own colors. In truth, the very first sequence in the movie shows a pink flower shining on a red carpet, extending into a chapel with mainly blue glass panels and pleasantly green pillars; summing up not just the colors of the characters but Totsuko’s role in connecting them.

Despite this constant presence, though, the film never feels like it’s unnaturally hammering the point. Yamada and Kobari’s graceful touch is guided by the former’s resistance against utilitarian artistry; for a director who builds upon meaningless daily life and who frames fictional characters as people who exist beyond the camera’s reach, it would be unnatural to make every artistic choice hold a singular meaning—let alone the same one—and ignore the whims of their imagined personalities. Though Totsuko always grabbing a red apple for her lunch is likely tied to her color, since that was part of her own introductory example, her tendency to wear those tones may simply be due to the director thinking that she likes them. With that mindset, she sells the cast once again as autonomous people, not just as preprogrammed vehicles for bullet points.

Another reason why the film avoids falling into a monotony of the main trio’s colors is that the palette is more broadly used for storytelling purposes, with striking results at that. While Kimi hides the truth about dropping out from her lovely grandma, back-and-forth shots contrast the old lady immersed in homely colors and Kimi lingering in gloomier hallways; the architecture itself contributes to this too, enabling singular shots where the grandma is surrounded by those lively colors while Kimi sits on the same table—except she’s framed by the dark doorway. Meanwhile, the contrast between a restrictive net of brown branches and bright green leaves brilliantly introduces Rui’s mother to the group. With such elegant delivery, the movie underlines the pressure these teenagers feel, but also that they’re still surrounded by loving peers.

The usage of color alone would suffice to tell this story in memorable fashion, but for a director whose movies are so easily watchable, Yamada’s approach has grown to be rather complex. There is much to appreciate about its choice of the theremin as a main instrument in the band, which not only brings their sounds closer to the spiritual roots of a group with two (now one) Catholic school students, but also gives a very tactile feeling to Rui’s playing—something that brings him closer to Totsuko’s synesthetic sensibilities. Unsurprisingly, the acting further elevates it as well. The animation in the film isn’t always as precise as it is during his heavily referenced performances, nor as it was in Yamada’s previous films, but it makes up for that through sheer joy and extroverted charm. Through a correction process that clearly involved not just designer and supervisor Takashi Kojima but also Yamada herself, the main characters always move in a way that feels uniquely like themselves; be it Rui’s giddy demeanor, Totsuko’s tendency to spin, or her chubby roommate’s side winks.

As those most acquainted with the director may already know, her films have had a tendency to mix those straightforward pitches—by her standards at any rate—with concepts that come out of left field, often drawing from fields like mathematics and physics to depict the state of relationships. The Colors Within places a lot of emphasis on the properties of light in this regard, as the vehicle for the colors that are integral to their story, but it leans just as strongly on something else: circular, spinning motions, and the idea of gravity that is derived from it. That is precisely the type of natural, unavoidable attraction that Totsuko feels to people with beautifully colored souls; something that is expressed in literal fashion through planet imagery, as Totsuko gets smashed by Kimi’s ball in the face because she was ensnared by her blues.

As a child who grew up around ballet classes, many of Totsuko’s mannerisms have flowery spins to them, and she herself still holds a frustrated dream of properly performing Giselle one day—one she gave up on because her physique and slightly clumsy condition don’t let her pull off the trickiest moves. Nonetheless, she spins round and round through life, having lost none of her underlying joy. Just like the circles she often draws, just like the improv round dance of happiness when the band gets to practice again together after a brief separation. Everything in this film moves in this circular fashion, and more often than not it does so around a protagonist who doesn’t realize that she has the same attractive effect as those she gravitated towards; if anything, her gravitational pull is stronger, because the meaning of her red is becoming clearer than ever.

In the first entry for The Color Within‘s ongoing series of staff interviews, Yamada refers to music as a means to share something you love. Across the film, each main character composes an original song that embodies that spirit, but no one accomplishes it as well as Totsuko herself. Her song is silly, amateurish, but bursting with her honest way of engaging with the world. It once again draws from that spinning and gravitational motif; in her desire to share Kimi’s color with the world, she feels excitement (wakuwaku, わくわく) and her mind immediately drifts to rotating planets (wakusei, 惑星). Her lyrics happily mix those celestial bodies, her faith, and her favorite lunch like it’s the most natural thing in the world. And, out of all performances, it’s hers that gets the entire audience going. Students who thought of her as a weird loner rejoice around her peers, and nuns joyfully dance to it—again, in Totsuko’s contagious spinning motions.

The first word you can hear after that joyful performance is someone in the audience screaming I love you. The next one you can see is those same words plastered in their background—cropped from a Love Your Neighbor backdrop to their stage. And then there is Totsuko, who realizes her Giselle dreams through a oneiric sequence that finally allows her to see her own color: the red of love, befitting someone who naturally cheers up anyone who approaches her with honesty. The movie (correctly) assumes that it has earned a few victory laps after that, including a neat shared materialization of Totsuko’s synesthesia through the colorful streamers sometimes seen as ships depart. However, it’s that ecstatic performance and the following moment of self-actualization that I’ll remember most as the beautiful climax for Naoko Yamada’s kindest film. That, and Totsuko’s aggressively catchy song. Maybe watching this movie months before its proper release was a bad idea, because now I’m addicted to a song I can’t even listen to.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

Good writing but SO JEALOUS MAN😭😭😭

Im going to ask though I think I know the answer. What Naoko Yamada movie is Colors most similar to?

Stylistically, it’s definitely Liz. It’s a dangerous comparison to invoke (especially in aspects like the performance animation, which theremin aside isn’t exactly on par) but at the same time it’s distinct enough that it feels like it’s excelling at its own thing. Between this and Anzu-chan, it really felt like we were getting offerings more aimed at people who enjoy Japanese cinema than anime per se.