The Transition Between Ufotable’s Experimental Past And Polished Present: Kara no Kyoukai’s 15th Anniversary

The experimental ufotable of the past and the current finely-tuned blockbuster makers feel like entirely different studios. 15 years ago, Kara no Kyoukai began that transition: laying their modern foundation, but also embracing their originally chaotic and subversive ways.

The cutthroat environment of the anime industry urges studios to develop a strong identity, something to set them apart from all other production companies in constant need of new contracts. And yet, it’s the way that same business functions that makes it hard for them to develop one. When the vast majority of creative talent is either fully freelance or just temporarily contracted, and the environment encourages nothing but a race to the bottom through outrageous levels of overproduction, organically developing a consistent in-house ethos isn’t easy. Your average studio can count themselves lucky if they’ve built the most surface-level brand, like those that have earned a reputation for being adept at tackling one particular genre; those preconceptions might not even stand up to the lightest scrutiny, as they likely relate to freelance staff who won’t necessarily stick around, but that alone can help them stay afloat.

As a consequence, it’s not every day that we dedicate time to talking about the studios themselves on this site, as the more meaningful connections are purely personal. At the same time, though, the studios that do have a distinct animation and labor culture that affects their work are recurring topics over here, since that singularity makes them a whole lot more interesting. One such place is studio ufotable, whose history, works, and internal synergies we’ve written about at length. When going over their past for their 20th anniversary, we split their history into various pivotal stages, but when it comes down to it, there are two clearly distinct eras of ufotable: their delightfully weird, experimental beginnings, and the current finely-tuned blockbuster producers. Exceptions exist to varying degrees in both periods—both purely commercial early ufotable works and more daring modern projects—but it’s clear to the eye that, even with foundational principles still resonating within the studio’s walls, their work then and now looks completely different.

When it comes to anime studios that have clearly distinct eras like this, the changes rarely manifest in an immediate, absolute manner. Even with something as radical as complete leadership overhauls, the scale of commercial animation production means that you won’t get to appreciate the next stage of the studio until multiple years and entire projects have passed. After all, more immediate results are a consequence of all sorts of decisions taken beforehand. In ufotable’s case, the management never changed—not even after their president and founder’s tax evasion—but their creative leaders certainly shifted with time and through certain departures; and as you might know, those ripples reshaped not only their works but also interesting projects elsewhere. While that change was gradual and not perfectly sequential, there happens to be one transitional project that perfectly connects the old and new ufotable. A series of movies that resembles their modern output to a much larger degree than its concurrent projects, and at the same time, a production that embodies the subversive, sometimes downright chaotic practices of their experimental era better than many titles made back then. And that’s Kara no Kyoukai.

The young ufotable of the mid-00s may not have had a hit to their name yet, but to understand how this project came to be, it’s important to grasp the fact that they immediately caught the attention of keen eyes. As we’ve brought up before, specialized animation outlets like AnimeStyle latched onto them after their first proper series Dokkoida; such was the appeal of bold newcomers standing in opposition to the status quo of anime production, with an in-house emphasis despite their small size but also magnetism for freelance artists who enjoy bombastic animation. The more time passed, the more ambitious their madness became—and do you know who adores an up-and-coming studio with the production muscle to back up their dreams? For the good and for the bad, this is something that producers like Aniplex’s Atsuhiro Iwakami simply can’t ignore.

Iwakami had been ruminating about how to put together an adaptation for Kara no Kyoukai that actually lived up to the potential he saw in Kinoko Nasu’s world since 2004, and by the following year, the solution to his woes manifested in front of his eyes. Futakoi Alternative was an eccentric reboot of a milquetoast, twins-themed harem series. It reimagined everything about the original series into a simply indescribable mix of genres and crazy scenarios. The motto of ufotable’s founder Hikaru Kondo resonates throughout the whole series: if making as many things as possible is the way to ensure you’ll get some of them right, why not jump around from noir cinema, to sci-fi epics, then back to face some humanoid squids before some surprisingly earnest romance? For viewers like Iwakami, this irreverent spirit was a wake-up call about new ways to create animation. So, why not approach them when he was planning something grand that wasn’t quite like anything seen before in anime?

Now, it’s worth noting that Iwakami’s initial plan was much more modest than the series we eventually got. It’s known that he approached the studio with a proposal to turn Kara no Kyoukai into a film trilogy, and also that it was Kondo himself who fired back with a pitch to match the original 7 chapters of the story with just as many successive theatrical releases. But where did such confidence come from? A big part of it was inherent to the character of the studio at the time, always willing to tackle challenges bigger than themselves. However, they might not have latched onto this opportunity had they not happened to employ two key staff members—the eventual first director and animator to work on the series, though more on its curious production later—who already loved the series and Type-Moon works in general.

Those were none other than Takuya Nonaka, a founding member who’d emerged as a versatile director within ufotable, as well as an early reinforcement for the studio in Tomonori Sudo, who’d worked his way up to character designer status after first joining the crew in the aforementioned Dokkoida. Kondo approached them before any decision was taken, and given how strongly he decided to bet on this project, he must have bought into their passion for the title; something that makes Sudo’s confession in Kara no Kyoukai Gashu, where he admitted that his first reaction was wondering how the hell they were supposed to adapt a work like that, feel all the more amusing.

Given the positive reception and enduring popularity of Kara no Kyoukai, it’d be easy to romanticize the studio’s efforts as nothing but brave planning that panned out wonderfully, but the truth is that its production consistently crossed into outright reckless territory; those aren’t my words, but something Nasu himself jokingly pointed out. The making of this series of films followed a recurring pattern where the team’s enthusiasm would continuously inflate the scope of the project, inevitably causing the plans to fall apart—and there began the time to start dreaming too big again. As previously mentioned, the plans immediately took a leap from a trilogy to a whole seven films. Their intended length also inflated as much as three times the intended length, going well over the planned 40 minutes for each chapter to clock two full hours for a couple of films.

This was of course not sustainable, and thus the first major concession they had to make was the pacing of their releases. In this September 2007 AkibaBlog interview with Nasu that you can find translated here, the original author still maintained that Kara no Kyoukai would follow a monthly release pattern. The series would premiere just a couple of months later and indeed follow those plans for a little bit, but the studio quickly grew so overwhelmed that the wait for each new chapter had to grow increasingly longer. Nothing illustrates this concession better than the gaps between the first and last couple of films: 28 days between #01 and #02, nearly 8 months between #06 and #07—still a fast turnaround given the workload, but one that was more feasible than the initial pipe dreams. Years later, key staff members could only poke fun at how ridiculous Kondo’s initial premise of putting out 7 movies in 7 months had been; though frankly, the fact that the team genuinely bought into it is the most telling part about what the studio was like at the time. Bursting with passion, talent, but not with common sense.

Before we tackle all the movies, it’s important to understand how the studio organized their production; and in doing so, you’ll see why approaching each of them individually is necessary. A goal of ufotable since their founding has been to flatten anime’s very strictly hierarchical organization. The whole studio is named after one particular round table—a piece of furniture everyone could sit around as equals. While plenty of management positions still exist within the studio and their projects, meaning that they’d be closer to a rectangular table with heads, they’ve succeeded in blurring the lines between positions and in giving a voice to many individual staff members. Although this was most obvious in their radical early stages where they’d constantly challenge traditional production models, it’s the same spirit that has brought them to establish hybrid departments where usually separate artists like painters and compositors work together. For as different as modern ufotable works appear to be from their early predecessors, the studio’s core philosophy remains the same.

Having recently hit its 15th anniversary, Kara no Kyoukai’s production was much closer to those subversive productions of early ufotable. Under the lead of experimental creators like Takayuki Hirao, the studio had questioned what it means to direct a project. Futakoi Alternative, the unlikely trigger to this whole project, featured two leaders with different points of focus and neither standing atop the other. The clearest example of those practices, though, was an original cult hit by the name of Manabi Straight. The studio’s last major project before Kara no Kyoukai made an explicit point: they granted specialized, equally standing directorial roles to all the pillars of the creative process. Ryunosuke Kingetsu wouldn’t be a mere scriptwriter and series composer bowing down to a series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario., but rather a story director himself. The input of character designer Atsushi Ogasawara and de facto lead animator Takuro Takahashi would also be held in equal esteem, after all, they were the visual director and layout director respectively. Hirao’s position as technical director tracks more closely to that of a standard series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario., but their attempt to create a more even field was clear as day.

So, what would a studio with little respect for directorial hierarchy do when entrusted with a demanding project that was meant to keep a blazing fast release pacing? Hand out every movie to a different director, with not a single chief to rule above them, and allow them to do as they pleased. Normally, studios would build around a central leader who’d deploy unit directors when needed—kantoku and enshutsu respectively—but in perhaps their last major shake-up of standard production practices, ufotable did essentially the opposite. The different backgrounds and levels of experience of each director in these 7 films are palpable in the way they interpreted their chapters. Although complete artistic freedom isn’t really in the cards when adapting the work of an author that was already quite a big deal at the time, the personal leeway they were granted makes each of them a pretty distinct experience. To best appreciate those differences, and finally find out what Kara no Kyoukai is all about, let’s take a look at each film.

Kara no Kyoukai was Nasu’s first published work, and while he wasn’t aware of that at the time, it shaped up to be a prototype for some of his most famous works. By its own nature, it’s rough, juvenile, and sometimes embarrassing—so much so that he begged for a chance to rewrite certain parts during the pre-production process for the anime. The first chapter Overlooking View in particular is one Nasu found most clumsy, but after seeing how this team was approaching it, he felt confident in leaving it all up to them. Sure, ufotable had gathered massive fans of his work who wanted to deal with the text as it was despite the author’s own apprehension, but they weren’t timid in their approach. Each director in their own way—and admittedly to different levels of success—attempted to mitigate the obvious flaws of a maiden work, while boosting the aspects that are still remembered fondly to this day.

And what exactly are those? Kara no Kyoukai is a dense work, arguably to its own detriment. It’s an anachronical narrative that drops you in the midst of Ryougi Shiki and Kokutou Mikiya’s adventures with the supernatural, introducing many fantastical concepts—like Shiki’s famous Mystic Eyes of Death Perception—that are always intertwined with philosophical ones. Each chapter has a flavor of its own, tweaking the thriller, horror, action, and even comedy sliders as is seen fit. For every poignant idea it introduces over the course of that story, you’ll also have to sit through a handful of pretentious conversations. Mind you, I don’t mean this in the way the internet has corrupted the word to mean secretly shallow and terrible, but rather its actual meaning: overly preoccupied with projecting more gravitas than it actually carries, which is perfectly understandable from a maiden work. If you’re not the biggest fan of Nasu’s philosophizing, you might be scared to hear that it’s at its rawest here, but as someone who enjoys Kara no Kyoukai, let me make something clear—that stuff doesn’t particularly matter.

At its core, Kara no Kyoukai is a pretty cute love story that asks itself whether it’s possible to stray away from your fate; to put it plainly, Kokutou claims that he can fix her, even if the fixing involves getting over a pesky character flaw such as a predisposition towards murder. While not a groundbreaking scenario, its commitment to that relationship in spite of all the extraneous elements makes it work, and Shiki in particular is a slaughterer with very charming body language that evolves according to the major shifts to her character.

At the same time, these films are also highly atmospheric and committed to the sensorial experience in a way that no other Type-Moon anime is. While the expository worldbuilding and dense dialogue that Nasuverse works are known for are still very much present, the Kara no Kyoukai films are also willing to stay silent for minutes at a time. The mystery aspect to these films—Shiki and Kokutou work for Aozaki Touko’s detective agency after all—is honored with an appreciation for the mystique; even if you know that long-winded answers are likely to come, they tend to relish the opportunity to soak the viewer in the grim, mysterious atmosphere of its world. There is a quiet appreciation of the things that are yet to be known, and those that may not be spelled out.

The delivery of the first movie makes those priorities clear right off the bat. Heading this first chapter of this story is director Ei Aoki, a relatively unknown face at the time whose rise to stardom coincided with his decision to partner up with ufotable. Through shows like Fate/Zero, Hourou Musuko, Re:Creators, and Id:Invaded, Aoki has earned a reputation for his emphasis on subjectivity and cinematic staging, two aspects that are very much present in his take on Kara no Kyoukai. The first shot of Overlooking View presents the recurring motif of Shiki’s eyes widening upon Kokutou’s arrival, immediately followed up by a more direct attempt to put the viewers in the shoes of these characters: a first-person cut of Shiki opening the door, the first of many shots of this kind. POV sequences are scarce in anime, in no small part because they’re inherently tricky to execute, but Aoki is so adamant about their usage that at this point even his protegees’ protegees frame daily actions in such a manner. And, for a series that ultimately just wants you to care about these two, details like this in the first film do a lot to set the stage.

If the introduction to its main characters is deliberate, so is the first taste of the texture of its world. For as memorable as its moments of high-octane action were, proving that Aoki is indeed good at presenting the Hollywood spectacle he loves, those only come after an arresting, gradual build-up. Shiki’s first encounter with peril dedicates a minute and a half without spoken word to transition from her mug to an actual foe; especially inspired is the shot that, coinciding with the crescendo of the music, finally shows traces of blood through a dog’s footsteps. For all the confidence in the direction, it’s worth noting that a big reason why this meticulous approach lands is the stunning art direction. In his Gashu interview, Sudo admitted that the weight of the word movie scared the staff, especially those of his generation; theatrical animation at the time carried a gravitas that it has unfortunately lost with time, and prior to the Disappearance boom, all that came to mind for them were epoch-making films like Patlabor and Satoshi Kon’s works. And who did they feel bailed them? Nobutaka Ike—art director for the first, second, and fifth Kara no Kyoukai films—who had a history of working on… Patlabor and Satoshi Kon’s works, in fact. Ike’s artboards, packed with lived-in details and oozing with that grim atmosphere, gave them the confidence that they belonged on the big screen.

While impressive at the time, not every aspect of the presentation has aged as gracefully. Although it is competent, its character animation shows few flashes of the level of thoroughness that is expected from theatrical animation—a specter of acting stiffness that has followed ufotable even as they’ve become a true powerhouse. Where it enters truly uneven territory, though, is in the compositing process. Kara no Kyoukai marked the promotion of Yuichi Terao to photographyPhotography (撮影, Satsuei): The marriage of elements produced by different departments into a finished picture, involving filtering to make it more harmonious. A name inherited from the past, when cameras were actually used during this process. direction duties, and in this aspect too it feels like a maiden work. It established the framework of what has with time become one of the most popular anime aesthetics, now with Terao leading all of the studio’s digital work. His heightened photorealism twists true-to-life ideas—particle effects, nuanced darkness, translucency—in the opposite direction, using them to increase the fantastic feel; the nights that shine blue are one of many quirks already present in Overlooking View. The overall execution of those ideas, though, cannot compare with the current polish of the studio. Its motion blurs are inelegant, rim lighting hardly feels authentic, and the cohesion of modern ufotable’s more in-house environment simply isn’t there yet. Admirable first attempts, but not the most elegant in retrospect.

The second film in the series, A Study in Murder Part 1, is an interesting one to look back on. Stylistically, it feels like an escalation from the first one—or perhaps a descalation, since it takes the more subdued qualities of its predecessor to craft an actual horror movie shrouded in mystery. Looking at it as a mere successor, though, would be a big mistake. For starters, there is no actual predecessor to this chapter, as it was the first one that entered production. This has been documented by multiple staff members, most notoriously including Kara no Kyoukai’s sole credited scriptwriter Masaki Hiramatsu. A Study in Murder Part 1 moved ahead so fast that, by the time the writer joined the project, this film was already in advanced pre-production; they’d wrapped up a preliminary script based on the source material, so Hiramatsu merely corrected it during the storyboarding phase throughout his daily meetings with the director.

How come A Study in Murder Part 1 blazed ahead, then? For starters, there’s the fact that it’s the chronological beginning of this story, covering the first meeting of Shiki and Kokutou, as well as a serial murder case they may have been involved with. More importantly, though, there’s the fact that the aforementioned Takuya Nonaka was entrusted with directing this one. Kondo didn’t simply ask the two big fans of the series in their ranks how they’d feel about adapting it. After getting their approval, he made sure to channel their positive energy into the work by entrusting them with important roles in that project; as Sudo himself explained, it’s kind of a policy at ufotable to make individuals work on what they like. As a consequence, he became the main character designer and animation director for the series, while Nonaka was entrusted with directing a very important early chapter—one that, given his familiarity with the material, got to move to production stages faster than even the film set to release first.

That grasp on the material explains how A Study in Murder Part 1 maximizes the qualities that the first film presented but perhaps couldn’t fully realize; which is to say, that the atmosphere is thicker and more unsettling, and the central couple’s antics in the midst of murder sprees are even cuter. This increased commitment to both sides of it over essentially everything else can be felt with its even more daring quiet scenes; the peaceful rain and Kokutou’s copyright-infringing humming melt Shiki’s defenses… until the viewer, who’d make the mistake of growing relaxed as well, is assaulted by her murderous worries.

Nonaka does introduce some gruesome horror elements through incidental events, just like Aoki did with a passersby dog casually revealing a puddle of blood through its footsteps. While the latter is quick to hop onto the extended spectacle afterward, though, Nonaka’s alternation between moods never allows you to become too comfortable as a viewer—an unsettling experience that remains one of Kara no Kyoukai’s greatest triumphs. Those flashes of horror are depicted with a degree of photorealism never seen in the previous chapter, and on the whole, his storyboarding is more pointed than Aoki’s as well; a contrast that makes sense, since Aoki’s background as someone who got into animation via digital tasks like compositing makes him more likely to rely on camera movement over meaningful static framing. With his more traditional animation toolset, Nonaka’s direction instead focuses on aspects like giving a physical dimension to Shiki’s attempts to isolate and box herself out through his compositions—quite effectively at that!

After two measured films to begin the series, Remaining Sense of Pain is certainly a doozy. A big factor in that is that it was directed by Mitsuru Obunai, who is in fact not a director. Mind you, this is not an indictment of his skill, but rather a statement about his career. Up till the production of this film, Obunai had essentially been a pure animator for decades, only dabbling in tasks like storyboarding and episode directionEpisode Direction (演出, enshutsu): A creative but also coordinative task, as it entails supervising the many departments and artists involved in the production of an episode – approving animation layouts alongside the Animation Director, overseeing the work of the photography team, the art department, CG staff... The role also exists in movies, refering to the individuals similarly in charge of segments of the film. on the side; under a handful of cases at that, and precisely in unorthodox ufotable productions that were willing to entrust works to bold, inexperienced candidates. He had of course never led a project of his own, and that has essentially remained the same to this day—with minor exceptions like the mostly forgotten Toriko pilot that the studio animated in 2009. But given his status as a regular contributor to the studio’s works, their curious directorial arrangement, and the sheer workload that entailed, he ended up with this new challenge landing on his lap.

Obunai’s approach was coherent with that background of his: in contrast to the preceding directors, he emphasized the sheer visual impact of the film by leading its production from the animation front, where he acted as co-designer and animation director alongside Sudo. Even when not as purposely framed, the draftsmanship of the drawings boosts the visual charisma of the entire film, especially when interacting with the work of a compositing team that pressed the accelerator just as hard as Obunai.

It’s worth noting that Obunai isn’t a simple animator turned director, but rather one of their most dynamic, visually aggressive aces. While there’s a common belief that ufotable’s animation is characterized by its smoothness—and their usage of interpolation in modern times contributes to that—the truth is that a bunch of their most renowned animators like Masayuki Kunihiro, Go Kimura, and of course Obunai himself trend towards snappy timing instead. Under his direction, Kara no Kyoukai ditched the more three-dimensional camerawork seen in the first film’s action in favor of more uncomplicated coolness; an approach that could also benefit from the snappy timing he maintained through his dual role as animation director. I believe nothing else sums up the film’s specific appeal as Keisuke Watabe’s highlight scene: a straightforward confrontation that culminates in a perfectly executed Obari Punch, with a fist that just so happens to be holding a knife for extra cool points.

The downside to this bluntness, and in a way the risk of this project’s unconventional directorial team, is that you can end up with someone who doesn’t have the finesse of a seasoned director dealing with material that demands tact. With its cool spectacle, Remaining Sense of Pain gets away with a simpler mystery that ultimately resolves into something that’s more of a punchline than an answer to a riddle. The symbolism being reduced to its most basic forms isn’t an issue either; it fits the general straightforwardness, and the extra oomph of the film’s presentation makes those very blatant shots feel more memorable than you’d expect.

Where it stumbles, then, is in aspects like its portrayal of sexual violence. Kara no Kyoukai as a whole deals with dark topics in ways that can feel pretty juvenile, and it just so happens that a pretty integral part of Remaining Sense of Pain‘s plot relies on assault. While it’s hardly the most exploitative portrayal you’ll ever come across, it’s rather crass and tends to linger on it more than necessary. At its worst, Kara no Kyoukai is like an edgy teenager trying way too hard to appear mature—and that’s not a good match for Obunai’s straightforward, loud, and blunt approach.

Although it never seemed to make as much of a splash as the bombastic films that surround it, The Hollow Shrine is a very interesting entry in Kara no Kyoukai, especially when compared to its immediate predecessor. Similarly to Obunai, Teiichi Takiguchi isn’t much of a director, also focusing on animation roles instead; if anything, he had less experience than him, as he’d never done any directorial work other than three storyboards years prior at Telecom. By working there, though, he’d befriended a coworker by the name of Hikaru Kondo—and guess what, that same person had now founded a studio and was looking for people to fill in 7 director chairs. Takiguchi hadn’t really been involved with ufotable in their early years, but he accepted this exciting new opportunity from an old friend. He clearly enjoyed that experience with them too, because while he did return to Telecom afterward, ever since 2017 he has moved back to ufotable in seemingly full-time capacity. His name may not be as loudly celebrated as the studio’s action stars, but this is how ufotable attracted by far their greatest acting specialist.

Different sensibilities aside, though, he led a production that shares many parallels with Obunai’s third chapter. His approach was also that of an animator suddenly entrusted with much broader responsibilities than they’d ever had to shoulder before, and thus doubling down on those aspects that they’re most familiar with to have a sturdy foundation to build upon. He followed his predecessor’s steps in acting as co-designer and animation director, duties that the project defaulted to Sudo and Takuro Takahashi for movies not led by near-pure animators like them; though, by the end of the series, the job went to whoever was around and somewhat prepared, as the studio could barely hold itself together after so much restless work.

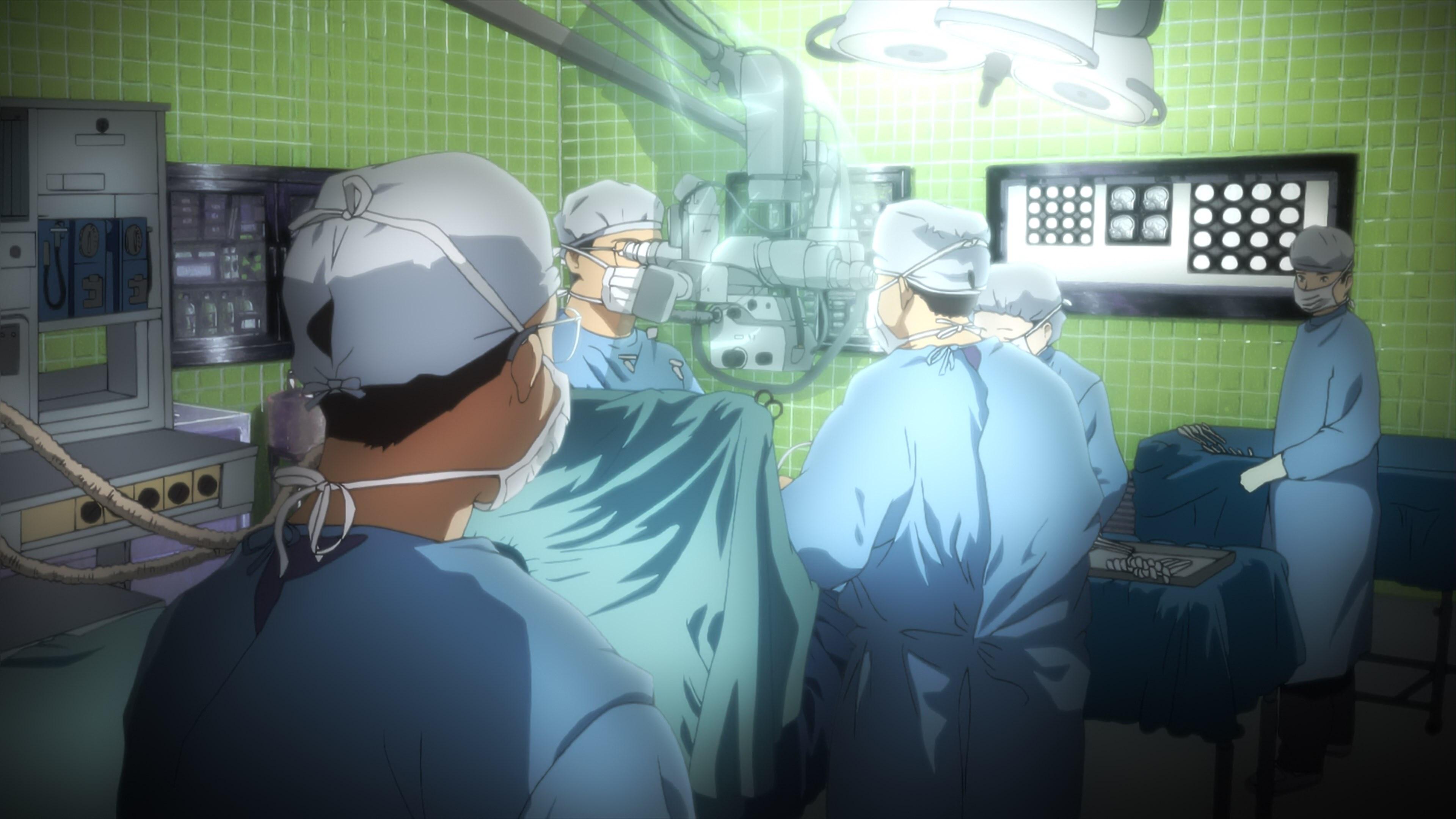

It’s precisely this shared angle that was the profound differences between the two movies so interesting. Right after Obunai’s bombastic spectacle comes a much more methodical film that is built upon Takiguchi’s excellent animation fundamentals. Its tone is much closer to Nonaka’s second film, the one it follows chronologically, but with a different flavor to its horror. This is a movie about the clash between the mundane and the supernatural, mortal flesh and the powers that transcend it. Takiguchi immediately captures your attention with unsettling realism; a lifelike seizure, the constant bobbing of an unconscious Shiki’s head, pupils reacting to light, the coordinated but still panicked medical intervention palpable in the subtle swaying of a stretcher, the weight of a body and also that of sheets themselves. Once Shiki awakens her Mystic Eyes of Death Perception and is forced to look at the overlap between those clashing realities, the fantastic depiction of her new ability immediately contrasts with the distressingly realistic SFX of her eyes being crushed and the ominous, weighty swaying of the sign a nurse has to hang on her room.

Even when it comes to the action sequences, and despite the chronological debut of Shiki’s iconic powers being done justice, the animation remains methodical and thorough. For an entire movie to keep up such a demanding act, one that the entire tone of the movie rides on at that, you’d need sturdy realistic animation, an eye for abstraction for the supernatural touches, and the efficient storytelling to enable the approach. Fortunately for them, they hit the jackpot with the risky bet for an outside director with no experience. Takiguchi’s movie is the shortest of the lot—excluding Kondo’s epilogue—and more focused for it, without really skipping any narrative beat. This shorter length and increased focus allowed him to draw the layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists. for 300 out of the total 470 cuts, and key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. for around 150~180 cuts of those; including several uninterrupted minutes right at the start of the movie, very precisely establishing what he was doing with it. Through this complete control, Takiguchi got to make the most complete and fully realized chapter of Kara no Kyoukai.

Paradox Spiral lives up to its name even in the contradictory position it occupies. On the one hand, it’s the lengthy and climactic confrontation against the main antagonist of Kara no Kyoukai as a whole. In his search for the truth of the world, Araya Souren paradoxically becomes the myopic force that has twisted everything against Shiki; in fact, he’s responsible even for incidents we’ve yet to see at this point, due to the nonlinear nature of this story. Given the part of this tale it covers, it’s hard to separate Paradox Spiral from the rest of the whole—and yet, it begs you to.

Contrary to almost every other chapter, the central figure of Paradox Spiral is neither Shiki nor Kokutou, but rather an accidental victim of Araya’s ploys in Enjou Tomoe. Though he does meaningfully cross paths with the main duo, his story is at the forefront—even in promotional posters—and is worth the price of admission by itself. The reason why this film in particular is strongly recommended even to those who have no interest in Kara no Kyoukai as a whole, though, it’s not just that you can technically watch it, but rather that you should probably do so if you’re interested in the formal aspects of animation and filmmaking.

Earlier, we pointed out that ufotable’s staff were intimidated by the idea of producing something worthy of the title of movie, but that wasn’t true for all of them. Takayuki Hirao, the brains of the studio’s experimental era, had inherited a reverence for film when he studied under all-time theatrical greats like Satoshi Kon as a young Madhouse employee. While he did feel pressure in directing his first movie all the same, the act of filmmaking was this near sacred experience he’d always looked up to; and, being a follower of a master editor of time and space, one that Hirao feels like it begs for non-linearity. The movie’s theme of eternally clashing opposites that take a form of a spiral is embodied by all sorts of cyclical imagery; stairs, the ying-yang, clocks, cogs, the constant turning of doorknobs, even a half-eaten ice cream. And when that motif meets a daring director who admitted he was dying to mess around with the flow of time, you get a non-linear movie where the script itself has also taken the form of a spiral.

This fascinating approach also heavily conditions the pace of the movie. Paradox Spiral was always the densest of all chapters in Kara no Kyoukai, and with all the jumping around different points in time, it has no room to spare for the lingering shots that had characterized the series at its best thus far. Trading away one of the best sources of the movies’ immersive atmosphere can sound like a risky bet, but Hirao more than made up for it with his enchanting editing. Though he did not yet have the finesse he showed in Pompo the Cinephile—a movie precisely about making movies, tailor-made for him—his rhythmic repetition and editing that keeps the forward momentum even as it takes snappy leaps is more than enough to keep you glued to the screen.

It also helps, of course, that Hirao is just as ambitious at presenting the animation itself; perhaps too much on occasion, considering that he managed to crash the studio during God Eater, a bitter experience that led to his departure. While he’s apologetic about it, Hirao admits he approached Paradox Spiral with no regard for efficiency, so the movie can count itself lucky by having only tested the limits rather than crashing through them. Its greatest achievements in animation are the lengthy sequences animated and storyboarded by his drinking buddy Tetsuya Takeuchi, who was frustrated that he didn’t receive offers for the type of continuous full-body action he likes to animate. Although Takeuchi didn’t have any storyboarding experience, that wasn’t going to stop anyone in a project where everyone was tackling new challenges, hence why Hirao gave him the keys to choreograph action as he wanted to make it. Though well, not entirely, because the projectile baby of his storyboards was vetoed and became a fire extinguisher instead. Hirao is the type of creator who always wants to test the limits, and I suppose he found some infant-shaped ones.

On paper, Oblivion Recording appears to be a side vignette. One that is peppered with details that relate to the overarching narrative, like absolutely all of Kara no Kyoukai is, but also a clear breather before the big finale and the most standalone of its original chapters. It shifts its focus from Shiki to Kokutou’s sister Azaka, which inherently involves a narrowing of the scope and lowering of the stakes; after all, it’s not quite the same to follow the philosophical conflicts of a death-slaying entity as it is to focus on an incestuous goof who appears to be the magical equivalent of dangerous fireworks. And yet, despite being a seemingly less important part of the puzzle, it’s precisely this film that comes closest to being the blueprint of what future ufotable would look like. And that once again comes down to a bold choice of a director.

Like other key figures we’ve been covering, Takahiro Miura also happened to cross paths with ufotable as a freelance animator during Dokkoida. Much like them, the vibrant environment of early ufotable must have caused a positive impression, because he’s been working with the studio ever since. Initially known for his passion for drawing cute girls, Miura was involved in all sorts of animation duties during their experimental era. However, as has been the case with half the directorial lineup thus far, he barely had any experience in that field—and certainly none leading an entire film.

This makes Miura’s case similar to those of Obunai and Takiguchi. Not only did he share a similar background and situation, but also a comparable philosophy when it comes to the relationship between animation and direction; which is to say, he’s outright stated that continuing to draw key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. is something he sees as a fundamental part of growing as a director. However, that’s also where their paths diverge in a major way: Miura has gone on to become a successful, very prolific director and especially action storyboarder. He’s not only ufotable’s go-to specialist even in their largest productions, but also on an industry-wide scale, for those studios fortunate enough to be able to enlist him.

In retrospect, Oblivion Recording offers very brief glimpses of the figure he has eventually become. The choreography is nowhere as involved as his greatest setpieces in Heavens Feel, but the memorable staging is already reminiscent of his current style—one that has become synonymous with ufotable as a whole, such is his gravity at the studio. Even when it comes to aesthetic choices and execution, Miura feels somewhat ahead of the studio’s timeline, offering a preview of the polish and dazzling digital work that you see in their later works. Ultimately, I don’t think that this tease of what was to come was enough to elevate a chapter that by design lacks what I believe to be the strong points of Kara no Kyoukai. As a piece of ufotable history, though, it’s an interesting and curiously prophetic film; I mean, it’s a movie about proto-Rin directed by the person who would direct the Unlimited Blade Works TV anime, the writing was on the wall.

By the time of A Study in Murder Part 2, ufotable’s initial plans for Kara no Kyoukai had completely crumbled; a pill that is much easier to swallow when you’re met with as much success as they did, admittedly. Not a single entry had stuck to the length they’d initially projected, and particularly ambitious efforts like Hirao’s Paradox Spiral had the whole studio shaken. The delays piled up to the point of becoming a genuine problem, as the director who was meant to handle this final movie was booked by the time the studio was finally ready to produce it. Only one person could step up to the challenge: Shinsuke Takizawa, a person best known for not actually being a person.

One of the recurring themes in this piece has been the studio’s disregard for traditional production practices, and their willingness to reformulate the role of the director. And so, with a rather exhausted team and a missing leader, it shouldn’t surprise you to hear that the Takizawa pen name hid 5 different directors with different contributions yet equal billings. Had Kara no Kyoukai attempted to maintain stylistic consistency throughout every chapter, this move might have blown up in their face—but for a series that never had a singular chief and gave room to each individual director to do their own thing, a chopped-up finale was frankly not that big of a leap.

Ufotable gathered as many directors from previous Kara no Kyoukai movies as they could, which meant the return of Aoki, Nonaka, Obunai, and Hirao. Joining them was president Kondo himself, always willing to be involved with any job at the studio. Unfortunately, Takiguchi couldn’t join them because he’d received work in the meantime, Miura never had the opportunity since this movie’s production began while his own wasn’t done yet, and similar conflicts prevented Aoki from actually drawing storyboards. In spite of this chaos, and in some regards because of it, A Study in Murder Part 2 is the type of wild film you get out of a passionate team running on fumes. While no two confrontations are similar, it’s got cool pieces of action in all those different flavors; sometimes it’s solid choreography and posing fundamentals, other times the camerawork is more involved, and there are even cases where that goes overboard, but in a charmingly overwrought way. Much of A Study in Murder Part 2’s lengthy 2 hours runtime is dedicated to something cool happening on screen, making it hard to care that there’s no cohesion to that coolness.

The downside to this chaotic approach is that this chapter happens to be one that could have done with some sensible rewriting, and that was clearly not an option when they were pressed for time and lacking a cohesive vision. Thematically, its focus on Nasu’s concept of the origin—the defining point of one’s existence that they naturally trend towards, especially if awakened—is worthy of being the finale of Shiki and Kokutou’s story. Can the former really escape her fate in favor of a more normal life with the person she loves? The answer is obvious to the audience and groom alike, but the resolution is nonetheless satisfying. Unfortunately, its narrative is otherwise Kara no Kyoukai at its most juvenile, hinging much of its plot on a ridiculous view of drugs. This forceful transition into animation did not smooth out those edges, but rather made them more awkward with its depiction of a comically evil villain who salivates several bottles worth of spit over Shiki. While this finale lands the beats that truly matter, it’s a messy experience overall; in a way fittingly so, as if it made a point to embody the eccentric nature of this project.

Ever since then, and despite its faults, Kara no Kyoukai has remained a beloved work. Not just the type that causes fans to fondly reminisce about it, but rather one with such an impact on the creators themselves to revisit it out of pure gratitude. In 2013, ufotable released Kara no Kyoukai: Mirai Fukuin, which can only be summed up as the accumulation of fondness and optimism the original series generated. Nasu wrote from a place of gratitude, having realized how much his worldview had changed since he wrote the original—a realization in great part triggered by ufotable’s lovingly crafted adaptation. Its companion piece Extra Chorus made that even clearer; first published as a comic born out of sheer enthusiasm for the Kara no Kyoukai films, its cute fanservice-y epilogues were brought to life by none other than Aoki, the director of the movie that started it all.

Mirai Fukuin itself embodied the growth of the studio and its personnel over this whole period. Its director was none other than Sudo, making his debut on a series that might have never existed if he didn’t give the OK to the studio’s president. Having played such a central role across the production of the series, and being as big of a fan of the Nasuverse as he is, it’s no surprise that Sudo identified the change the author saw in himself too. He elegantly summarized it as a reversal in the portrayal of light, which gives a physical aspect to the change in its worldview. The emotional core of Mirai Fukuin is two younger characters whose activities are set in the daytime, contrasting to the grim nights of the original. Its focus on the future and its possibilities feels like an evolution of Kara no Kyoukai’s themes rather than a refutation; one so stark that it’s hard not to smile at it, as if you were looking at a younger sibling who’s now all grown up.

And again, it’s not just the work that had matured, but the studio as well. In Sudo’s words, they went from experimental to incremental; rather than creating something completely new every single time, this served as a foundation to build upon. As a viewer, I won’t hide that I’ll always lament the loss of that outlandish young studio that would constantly come up with something you hadn’t seen before in commercial animation. When considering the reality of the anime industry, though, I can’t bring myself to blame them for having built this consistent, recognizable, and more marketable identity—especially given that it genuinely resonates with much of their staff.

Reminiscing about the past and how this project helped the studio, Sudo said that his freelance self couldn’t even imagine how working on the same series for several years could remain engaging. After his long dedication to Kara no Kyoukai, he actually found it an illuminating experience in that this consistency lets him recognize shortcomings address them more easily. And perhaps more importantly in the case of ufotable’s specific way of working, teams sticking together like this was a great way to identify every individual’s strengths. While ufotable is nowhere near self-sufficiency, Sudo pointed out the fundamental difference in how they approach a project versus how a standard studio does it. While the latter essentially gathers a new team every time—necessarily demanding good scouting if you need specialists—a place like ufotable always has the same backbone. As exciting as the studio’s smaller early works had been, with all staff involved having to figure out something new every time, it was Kara no Kyoukai’s massive undertaking that triggered their self-discovery process. 15 years later, this has become an amusing punchline: it was one of their most chaotic and subversive productions that led to the orderly, finely-tuned modern ufotable.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

that definitely was not a half eaten ice cream Kvin

Complitely accidental jumpscare, lol. It is now!

I’m glad that I sought out these films. They were truly something unique and really primed me for the potential of digital animation. I have no idea how they possible got these past the eyes of investors because they are weird weird WEIRD in terms of plot and worldbuilding. However, Film 5 is worth going through the whole thing for. Incredible triumph of animation. The films only look better from there, though they lose their narrative momentum because of how it’s all split up. They really are experimental and I’m glad ufotable got the opportunity to do them even if… Read more »

amazing blogpost as usual