Animating A Silent World – Yubisaki to Renren / A Sign Of Affection Production Notes

Both in the original manga and in its anime adaptation, Yubisaki to Renren / A Sign Of Affection combines extensive research and ingenious creative choices to respectfully, charmingly depict the world of its deaf protagonist. This is the story of a beautifully abnormal production.

Upon starting Yubisaki to Renren / A Sign of Affection, we’re immediately invited to Yuki’s world. Her reality is insulated from that of most people’s, but that doesn’t make her life gloomy. She enjoys cute fashion as much as she likes getting a good discount on the clothes she buys, and she’s got friends to share these common interests with; if anything, the subjective shift in the anime’s palette as she’s introduced indicates that her perspective is rosier than your average person’s. And yet, as indicated by a certain ringing noise and the omission of all diegetic SFX except those that cause physical reverberations, Yuki also happens to be deaf. Respectfully depicting the reality of people like her, while at the same time conveying the worldview we can already intuit in that introductory scene, was always going to be the biggest challenge for Yubisaki.

That wasn’t a new issue for the anime adaptation to face, but rather something that the original author was already aware of; or should I say, the original authors, as Morishita suu is a pen name shared by writer/storyboarder Makiro and artist Nachiyan. In interviews like this one for Spica Works—the agency for female mangaka they belong to—they’ve explained how they came to work together, as well as the backstory of Yubisaki in particular. The two of them are from the same city, and their shared love of manga led to a friendship that started when they became classmates at 15 years old. Though they’d had dreams of going professional with their hobby, as many kids do, by the point they met their attempts to submit their works to talent-seeking contests were already dying down.

It was quite a few years later, with the two of them having become housewives and remaining in contact despite having moved to different prefectures, that the idea of teaming up to reclaim their old dream was brought to the table. And of all things, it was Bakuman’s story that helped them realize they could combine their complementary skillsets to pursue that goal together. That decision was made on May 21 2009, and by the following year, they had already made their official debut. With two major serializations under their belt across the following decade—Like a Butterfly and Short Cake Cake, 12 volumes each—the preparation stages for their next work made them realize that there was a topic that the two of them had wanted to tackle: sign language.

Amusingly, neither had brought it up because they were aware of how big of a challenge it would be for the other; lots of research to deal with it properly from a writing standpoint, and just as much nuance to capture visually for that to pay off. While they were struggling to come up with a pitch that would convince their editor, Nachiyan blurted out that theme, and the two of them agreed that the extra effort would be worth it. With their ideas not fully clear but everyone on board, their research process began. Their own knowledge of sign language, specialized books, and various interviews they did were the starting point, but it was made clear to them that many details would need constant supervision by hearing-impaired people. Searching for that first-hand experience, they found their way to the sign language café where they met Yuki Miyazaki, with whom they hit it off so quick that she immediately became Yubisaki’s sign language supervisor; a fast friendship partly caused by the fact that she shared the name with their planned protagonist for the series.

To this day, they still meet Miyazaki every month to prod her with questions about how she might react in a certain situation, listen to her stories, learn sign language, or simply hang out. In the volume releases of the series, they summarized their actual working process like this: Makiro reaches out to Miyazaki with the storyboards to check them and learn the relevant sign language, allowing them to record videos of its usage, then send to Nachiyan so that she can begin drawing in earnest. Beyond this more mechanical help when it comes to depicting sign language, Miyazaki’s experiences have given them a better grasp of what Yuki’s daily life may be like; the way she’d position herself to read lips better, the types of words she may struggle with, or the specific ways in which sounds blur together.

Thanks to this, and with the help of their editor’s ideas as well, they’ve managed to make the expression of life for a deaf person into one of the best, most interesting aspects of Yubisaki. Besides the depth of knowledge about the topic they’ve accumulated and the accuracy of the sign language, what stands out the most is the ingenious ways they’ve found to translate those experiences into visuals.

Off the bat, you might notice that the opacity of the textboxes that represent Yuki’s lipreading is lowered. That serves not just as a way to capture her experience, but also to elegantly control the information, so that the reader can immediately tell whether the protagonist has caught a sentence or not—quite important when dealing with a deaf protagonist. This trick is further expanded into the text being flipped or garbled together when Yuki can’t read it (often with unfamiliar, uncommon words, as the authors were told often happens), and even plays a part in emotional climaxes. A way to put the reader in Yuki’s shoes in such a moment, for example, can be to randomly distort the font size when she’s teary-eyed to show her struggle to read lips at the time. With a solid foundation of first-hand experiences and technical knowledge, as well as the right amount of smart visual tricks, the way Yubisaki conveys hearing impairment has deservedly earned a strong reputation.

While this explains the how, a very important question remains: what does Yubisaki convey? In a way, those meetings like Miyazaki also helped solidify the concept the authors had in mind. Watching her act like a perfectly ordinary girl drove it home that Yuki the character ought to be more than her condition, that a deaf person is first and foremost the latter. They were wary of taking an overly moralistic angle, and also didn’t want to twist that sense of realism they’d fostered in a gloomy direction, where Yuki’s deafness was an inherent, inescapable source of angst. If anything, they wanted to create a love story that their new friend Miyazaki could happily call entertaining. Nachiyan expressed that she wanted to draw a manga that would hopefully inspire people who feel like they’re lacking courage, to help them take a step forward like Yubisaki’s characters quickly do. And that’s our chance to move onto the team behind the anime adaptation, because those goals called out to them.

In interviews like this one for Subculture’s Otaku Lab, series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario. Yuta Murano has explained that the project was first pitched to him in a private meeting with Kodansha reps, right after he had led the adaptation of Kakushigoto for them; speaking to Yubisaki’s magazine Dessert themselves in 2023, he placed that meeting 3 years prior, so we know for a fact that the project began in 2020. In both of those, Murano expresses that he’d always wanted to direct a shoujo anime, hence why he was quickly on board. And, since the project just so happened to be tailor-made for a certain someone else as well, he was never alone in that ship.

Writer Youko Yonaiyama has only been involved with the anime industry for a few years, but she already has popular works like Paripi Koumei under her belt as a series composer, as well as extensive contributions to hits like Uma Musume and Skip & Loafer. Besides this regular writing work, she also offers services like teaching sign language or live interpretation for events, which are noted in the same business card she uses within the anime industry—making it clear why she was offered the job. As she noted to Dessert, her personal experience as someone with deaf parents actually makes her somewhat wary of works dealing with that theme; in her experienced view, they’ll often fail to portray its reality, or simply exploit it for cheap melodrama. With its cheery spirit and their research showing in details like the distinction between Japanese Sign Language and Signed Japanese, though, Yubisaki had won over Yonaiyama before she’d even been offered the job. And so, she quickly accepted the job as well.

Upon reading the series himself, director Murano’s first impression was that it felt modern. That’s the term he used in the aforementioned interviews and this piece for Mantan Web to describe its worldview and how that manifests through its attitude towards the protagonist. Far from preconceptions of the past, Yubisaki refuses to impose heavy shackles like the label of disability on someone who doesn’t see their situation in that way. And, since Yuki’s outlook is much brighter and unburdened than that, the series treats her thusly. Murano was charmed by this mindset, so he emphasized during meetings that hearing impairment shouldn’t come across as inherently tragic. Often troublesome, perhaps, but never pitiful—if anything, he found the attitude of people like Yuki who will successfully communicate with others regardless something to be dignified. While he has made a point to say that there are excellent works out there with a more dramatic angle that capture the hardships of deafness, this wasn’t going to be Yubisaki’s goal.

An interesting detail in this regard was revealed in a more candid talk between Murano, Yonaiyama, and the Morishita suu duo on the authors’ fansite. When asked about his feelings about the work again, the director noted that he was about to reveal something he’d never disclosed before. Being offered this job had brought him back to his days in university, when he’d dated someone with hearing loss from one ear. She volunteered to take notes for fully deaf students, and at the time, Murano wondered if there was something he could do to help out as well. In the end, he was never able to take that step… which may have contributed to that relationship coming to an end, so his inability to act at the time still haunts him in his dreams sometimes. In Yubisaki, he saw a series about people who have the courage to do what he couldn’t bring himself to, so giving his everything in this project has relieved him on a personal level too.

Murano and Yonaiyama proceeded to praise the way Yuki proactively reaches out to others regardless of her condition, her courage to approach a crush who lives in an entirely different world than hers. Without realizing, they were using the exact same verbiage that Nachiyan had used years earlier to describe the feeling that fuels her when drawing this series: wanting to encourage those who feel like they can’t take the first step in a new direction. While it stars a deaf protagonist, Yubisaki is not about deafness, but rather about a brave girl approaching a charming globetrotter. The two of them, one through her sign language and lipreading and the other through his vast experience with foreign cultures, are bound together by their emphasis on communication. They see in the other something so familiar yet so unknown, prompting them to take that first step. For as important as it was to respectfully portray people like Yuki, this is the actual core of the story, and why its creators see it first and foremost as an idealistic shoujo romance; one that uses reality to ground the lived experience of people with hearing impairment, but that remains deliberately starry-eyed otherwise.

After explaining how the manga manages to capture the reality of a deaf person, and what its original authors and anime team are on the same page to convey, it’s time to circle back to the initial question: how does the anime translate all those ideas? While the themes were clearly established, the format change necessarily implied rethinking the storytelling, both in scope and technique. Given, for example, the reliance on different text renderings to deal with Yuki’s condition in the original, an anime where that aspect is much less present—though not completely gone!—would have to come up with compelling alternatives. And to do so without losing sight of the characters, the team opted to lean particularly hard on its core staff. Which is to say, on the two people we’ve been talking about.

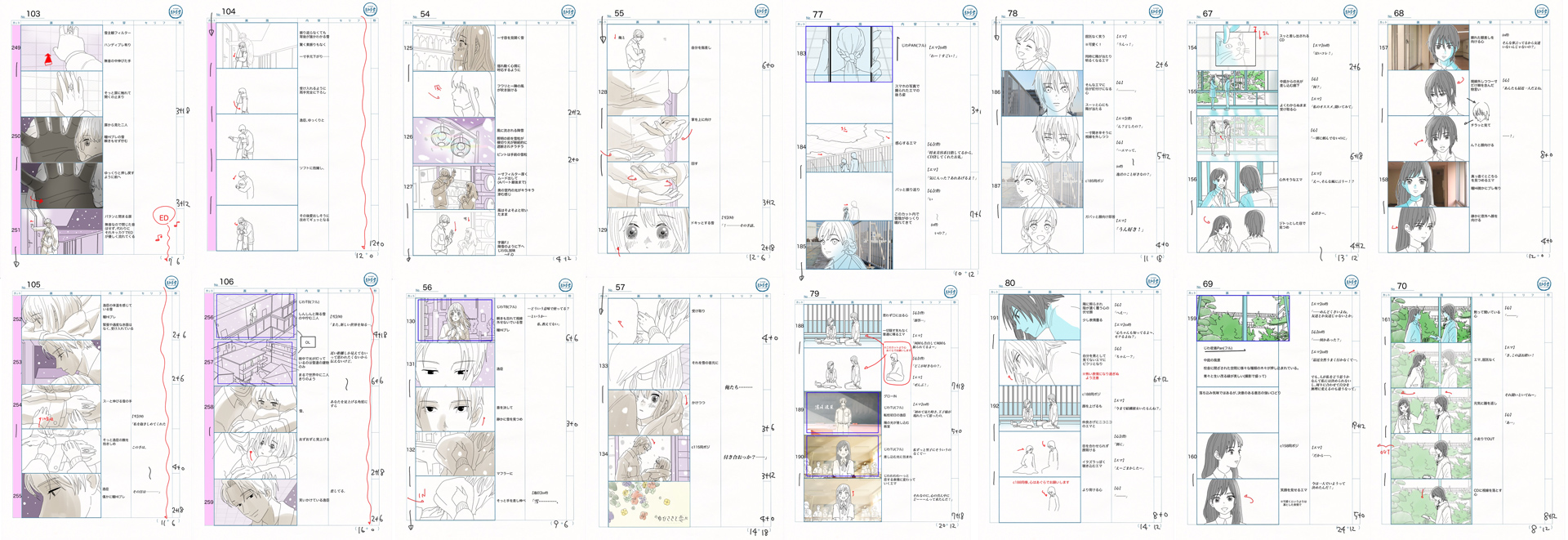

For writer Yonaiyama, this was the first project where she wrote every single script; not unheard of, but still quite the achievement, especially considering her role as the sign language supervisor as well. The point where things took a turn for the truly extraordinary, however, was in Murano’s choice to storyboardStoryboard (絵コンテ, ekonte): The blueprints of animation. A series of usually simple drawings serving as anime's visual script, drawn on special sheets with fields for the animation cut number, notes for the staff and the matching lines of dialogue. every episode as well. The director had always wanted to give a try to an effort like this, and Yubisaki’s specific needs made it a challenge worth tackling. In the aforementioned Mantan Web interview, he explained that the series simply has too many elements to keep track of; the nuanced and sometimes understated emotions, all the silent expressions from the manga that cannot be directly translated, the usage of the sign language and its interaction with the regular acting, and also the economy of it all. Had they entrusted this to freelance directors, it might have backfired and ended up being more work altogether.

In a later Animate Times interview, Murano added that even that wasn’t enough. By storyboarding everything, he could protect the integrity of Yuki’s depiction, ensuring for example that she’s always directly facing someone with whom she’s having a conversation—something that anime will usually play loose with, since directors want to make conversations visually engaging somehow. And yet, it’s not like he could simply forget those goals that his peers normally have either, since Yubisaki was still meant to be an entertaining piece of fiction. He had to control not just the staging and diversity of framing but also the tempo itself, while knowing that careless editing could shatter aspects like the sign language. He ended up taking even more work himself as a consequence, admitting that he was effectively an episode director for 8 out of the 12 episodes despite the credits not reflecting that. Murano had spent effectively all of 2022 storyboarding, and that was just the start.

For as taxing as that approach was, it’s undeniable that it paid off. The depth of the research and the attempts to expand Yuki’s world are obvious since the very beginning, with a morning routine chockful of new details that have allowed hearing-impaired viewers to recognize a life like their own; for example, a vibrating alarm clock waking her up, or flashbacks to a school of the deaf that was not depicted in the manga, complete with visual cues and mirrors in the ceiling for the students who can’t hear people approaching from behind.

These details often extend beyond a mere nod to authenticity and turn into compelling stylistic choices of their own too, much like the visual delivery of deafness in the manga did. Sometimes it can be a layer of live-action footage scrolling as the couple-to-be meets on the train, rather than relying on SFX to do the job of immersion as one usually would, because they wanted a sense of reality a deaf viewer could relate to. Sometimes, it can be the sound itself; Murano heard from deaf people that they perceived things muffled as if they were underwater, and his belief that Yuki would be so used to it she might find it oddly soothing led to a beautiful soundtrack that uses glass harps. Living up to the protagonist’s name, the falling snow plays a similarly evocative role. Even if the director (and the text itself) hadn’t noted that it’s a metaphor for the love accumulating in Yuki’s world, you may have already noticed how it pleasantly falls the second she becomes more conscious of her feelings for Itsuomi, how it accompanies them as their relationship develops, and even how it becomes more agitated in scenes where a more fiery character like Emma also pins for Itsuomi’s affection.

In one of his regular threads commenting on the production process, Murano talked about the many original additions being key to the success of the anime. Mind you, this was no diss to the original work, since he introduced the topic by talking about the careful process of grasping the source material with the help of its authors; he’d leave post-it notes for every detail that he wanted clarified, then worked alongside not just them but Yonaiyama as well in a process of naturally extending the manga beyond its boundaries he couldn’t have done on his own.

As he noted there, much of this original content involves introducing new imagery that is better suited for the anime and what he attempted to convey with it. The second episode starts with Yuki longingly staring at two birds flying freely, which is as straightforward of a summary of her outlook as an everyday shot can give you. The first episode already had done something similar with trails in the sky: a quintessential piece of inspirational imagery, and also a direct link to her crush’s love for travel, making them a recurring motif. Another couple of birds, one in the light and one in the shadow, represent Yuki’s two love interests beginning to clash with this early episode—not that there’s any real competition, since Yuki is immediately fixated on the one in the light. Murano’s theme for the episode was dichotomies: between romantic love and more disaffected longing, and between Itsuomi’s bright presence versus childhood friend Oushi’s clouded feelings, thus light and dark.

Though this conflict is gradually dealt with across the entire series, the second episode already lays it out perfectly. Oushi’s overly protective approach, shrouded in an abrasive attitude, simply never stood a chance with Yuki. His clumsy feelings aren’t only failing to come across, but also fundamentally clash with those aspirations that the imagery hints at. She has been hurt sometimes in the past, but that has never stopped her from dreaming of a colorful life of her own, which little by little she’s been working towards. When Oushi is effectively saying that vulnerable people like Yuki might be better off staying where they’re safe, he himself is in the shadow of a bridge, and in the sky there are trails soaring—that same motif they’d established for Yuki’s dreams and Itsuomi’s lifestyle. In contrast, the latter’s arrival brings light, reflecting in her eyes the same way the brightest skies in her youth did.

When Yuki starts pursuing Itsuomi more proactively in the following episode, another encounter with Oushi furthers that point. The childhood friend’s harsh warnings against going out at night are accompanied by warnings and red lights, whereas her decision to run to Itsuomi is preceded by the traffic lights turning green; he’s the one who encourages her to move forward after all. What’s most notable about this conversation, however, is how much of it is done through carefully animated sign language. If drawing that was already tricky for the original manga, despite relying on all the guidance we covered earlier and the format’s inherent abbreviation of actions, you can only imagine how troublesome it was to portray it more extensively in anime form. Or rather, you don’t have to imagine it: Murano has openly said it was a huge pain in the ass to do this for a TV show.

If you bring up sign language in anime, most people will immediately think of Koe no Katachi, and rightfully so. Its anime adaptation did its due diligence when it came to portraying the theme as well. They collaborated with the Japanese Federation of the Deaf, the Tokyo Federation of the Deaf, and Sign Language Island. There was a sign language supervisor and several coordinators, as well as several sign language models, so that each character who used them had a reference closer to their own characteristics. And of course, the production followed suit as well, with countless hand expression sheets and corrections, placing a huge emphasis on non-verbal communication. The results of all that speak for themselves, not just in the quality of the resulting work, but also in the personal consequences it’s had. Tamaki Kabasawa was only 16 when she acted as Shouko’s sign language model, and while at the time she couldn’t empathize with the character, she now looks back at the work as the one that saved her, as it helped her recognize that she’d found a similar circle of friends.

It’s through careful depictions that stories like Kabasawa’s become more likely to happen, but while Yubisaki has proved to have its heart in the right place, what about its production muscle? It’s one thing for arguably the country’s greatest team of nuanced character animators to nail the theme in a movie, but what can a less prestigious studio do on TV?

As it turns out, they can do excellent work as well. Ajia-dou might not be as popular of a brand, but they do have a chronicled history and animation culture of their own. The very same central figures in all-time classics like Yokohama Kaidashi Kikou remain at the company as its most reliable veterans, being entrusted with whatever the hardest job for each project happens to be. Some of them like Masayuki Sekine get to tap into the same skills that gave an unmatched sense of immersion to the likes of YKK, as he’s still their shot composition specialist—a role he holds in Yubisaki as well. By bouncing around tricky jobs, the other veterans have expanded their repertoire, which proved to be useful when they were given a new challenge for this series: acting as the sole sign language animators for the whole show.

Mind you, those 3 specialists—Yoshiaki Yanagida, Masaya Fujimori, and Yuki Miyamoto—did have some help to finish those sequences, but the animation layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists. were indeed all their work. First and foremost, Yonaiyama helped Murano choose which signs were the most important to feature, as they still had to be mindful of the production economy even within a project that clearly shaped up to be above TV anime norms. Once selected, Yonaiyama recorded herself performing them, and those sign language specialists would begin the animation process, each of them often handling every relevant scene for multiple episodes in a row; something they did while still handling some of the trickiest regular shots across the show. Their work was checked at a rough animation stage, and then once again once polished and painted. Even beyond that, Murano personally adjusted the timing himself if necessary, since as stated earlier the editing is something he mostly had to handle himself. Animation normally is a lot of work, and with a careful approach like this, even more so.

The reason why the director himself saw it fit to talk about this process coinciding with the third episode wasn’t just that it featured troublesome scenes like Oushi and Yuki’s signed argument, but also the fact that it was the first fully outsourced episode. This is a practice we’ve discussed at length, not just in what it involves, but also how it opens teams up to friction and incongruences. Though excessive outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio. can be very scary (especially with the current state of the anime industry), recent hits like Dungeon Meshi have also allowed us to explore its possibilities when applied to trustworthy assistants who are deeply acquainted with the core team. Yubisaki hasn’t had such high profile allies—shout out to a fan favorite, however—its lengthy schedule has allowed them to pull a different trick to bypass the usual shortcomings: making that outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio. not so full, keeping important tasks within the core team. Despite as many as 5 episodes being subcontracted like that, alleviating the total workload a fair amount, aspects like all the sign language animation and Murano’s personal checks never left in-house premises. While the polish fluctuates a bit across the show as a result, it maintains a beautiful threshold, and never threatens these delicate aspects that the series hinges on.

Another aspect that benefited from the project’s relatively ampler schedule was the occasional deployment of film scoring, allowing Murano to collaborate with composer Yukari Hashimoto for important scenes like the confession in episode #06 and the moment of intimacy at the end of that same episode, as well as the final moments of the premiere.

As Yuki and Itsuomi’s relationship advances, the attentiveness that manifests through all these techniques and processes makes a fundamentally simple romance incredibly charming. In her role as the sign language supervisor, Yonaiyama emphasized that they must see it as what the term indicates: a language. Accuracy is of course important, but they ought not to portray it like a series of gestures and poses you’d see in a textbook, because that’s not how sign language manifests in the real world. Murano understood the assignment and tried to avoid depicting it in a clinical, sterile way, instead underlining the human aspect through imperfections like making fingers tremble nervously, or even distorting the signs a bit so that they capture the emotion of the characters at the time. To this day, being told by deaf people that they genuinely captured their means of expression seems to have made him the happiest.

Though a surface examination of Yubisaki might tell you that there are a fair number of seasonal titles with higher production values and more character animation by sheer volume, it’s through consideration like this that I believe it gets elevated to actual character acting. And, combined with all the aforementioned ways that Murano has used to make the world itself convey emotional states and the unique qualities of Yuki’s world, it all comes together with a beauty you’ll rarely find in anime. Its well-meaning story is uncomplicated and nowhere as flashy as most popular titles, but that also helps its clear message come across without any obstacles. Like Yuki’s world, it might not make much noise, but it has a dazzling inner beauty to it.

To be perfectly honest, this type of project is not something we can expect to be easily replicated or followed up on—not even by its own team, who are also aware of that fact. Yubisaki was designed as a singular season that would graciously capture the spirit of the original work, rather than a recurring adaptation to fully adapt its events at any cost. To achieve a feeling of completion within these 12 episodes, Murano went out of his way to reframe later arcs and even portray unseen pasts, all with the collaboration of the original authors. Anyone who has been in the anime industry for long enough knows that they won’t normally get 4-5 years to adapt a TV show, with ample room to experiment and a source material that was already so deeply researched. Even if you work at a studio with reliable aces like Ajia-do, being able to lean on them to the degree that Yubisaki has is abnormal. We might not get another project like this in a while. But you know what? We did get Yubisaki, so again, you owe it to yourself to give it a try.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

Thanks for the excellent article. As I watched “A Sign of Affection” recently, I was wondering about how the show was able to display sign language in an engaging visual manner and this article helped answering that question. I also appreciated other aspects of Yuki’s journey beside the romance like when she looks for a part-time job or the overall theme of communication as a way to connect to each other.

Wish there was a show with a deaf charcter not focused on romance.