Koe no Katachi / A Silent Voice: Tactile Communication

Three years after its original premiere, we’re revisiting Koe no Katachi / A Silent Voice to talk not just about the movie’s triumphs when it comes to nonverbal communication, but also the immense struggle that many animators face to create the illusion of tactility.

As much as I hate being the bearer of bad news, let me tell you something: animation isn’t real. Not just in regards to us, but also in regard to itself.

To be precise, it’s certain types of animation that aren’t. If you look at the broader scope of the medium, there actually are multiple sub-genres with an inherent physical dimension to them. From the many applications of stop-motion techniques like claymation to even older artistry like puppetry, many performances that can fall under the umbrella of animation do incorporate a very material component to the art. In disciplines like that, it’s precisely that physical aspect that’s at the core of their charm. It boosts the experience in some obvious ways — like immediately rooting them in reality — as well as some subtler ones; even if it’s not as easy to pinpoint as the palpable quality of two characters with a real, corporeal form interacting, there’s also something indescribably satisfying about the movement of the particles in sand animation pieces, or in seeing clay morphing. It just tickles the brain the right way.

That’s not what most commercial animation that viewers nowadays enjoy is like, though. Your everyday modern project might still vary a bunch depending on the nature of the production, but when it comes to this, the conclusion it’ll arrive to is always the same: physical interactivity is a struggle. That stays true even in the case of 3DCG titles, which are inherently better suited to maintain a feeling of physical volume than hand-drawn animation, but at the end of the day are only emulating the corporeality of its world and characters; were it not for all the artists tweaking the work, no 3D show would hit that sweet spot between objects clipping through each other and everything sliding away without the feeling of contact, let alone manage to convey reactivity to touch.

What about anime as it is right now? Regardless of the advances of digital 2D production, and despite what a lot of naysayers online seem to think, they’ve yet to invent a button that magically makes animation appear out of thin pixels. And that means that for the vast majority of anime, the end product we see on our screens likely started in material (paper) form… though that’s not what’s actually presented to us, but rather scanned data made to interact with other digitized assets. Not only does the compositing team have to fool us into believing that all those pieces of art exist in the same plane of existence, though, yet another issue can come into play: the animation is often created divorced from itself.

One thing that might not be immediately obvious if you don’t have much art experience yourself, and even clash with your assumptions if you’re used to hearing that anime shots are supposed to be conceptualized as a whole by one key animator, is that most elements are drawn separately — not just separating animation and backgrounds, but different animated elements that inhabit the same shot too. Each character that comes into play will likely be on their own layer, as will each piece of effects, each anything, all for the sake of… being able to finish one shot without reaching nirvana, let’s say.

In the 2D plane of your screen, elements on the foreground will inevitably obscure something behind them, but you’ll need to draw their full arc of movement if you want to maintain the illusion that you’re depicting a world with a continuous existence. And even if these individual pieces don’t happen to cross paths, it’ll most likely be more feasible to keep track of the particular trajectory and kind of movement you wanted to imbue that element with if you draw it by itself. Which is to say: if you’re a mere mortal who wants to keep their characters, props, and explosions consistent and true to your vision throughout a shot, layers are your friend.

Now there’s no denying that this layered approach works decently well — there’s a reason it’s used — but that doesn’t mean that it’s always easy to navigate for animators, who already struggle plenty to create that feeling of physicality by itself, regardless of their technical approach to the shot. To give you a concrete example, just a few days ago, an acquaintance reached out with a very specific request: since they’d been entrusted with a hand-holding sequence for the first time, they wanted some references of how those are usually drawn, not just in terms of the drawings themselves but also whether each hand tends to be separated into its own layer or not.

After digging up a handful of reference materials, the answer turned out to be a resounding depends, as artists simply try to find their own answer to this whole dilemma. From a not necessarily representative sample size, we did notice that drawing a hand extending to another and then holding it in separate layers appeared to be a bit more common, even though it required the artist to go out of their way a bit more to make the action truly convincing. Meanwhile, the slightly more unusual instances of same-layer hand-holding somewhat force them to nail that feeling tactility, at the cost of presumably being a pain to draw. No real wrong answer, simply a matter of the priorities of the scene, personal preferences, and the scope of the work. And by the way, the animator in question was later told that the scene they’d requested of them and that he’d already put a bunch of effort in was passed to another person, without any notification. Yay for anime industry anecdotes!

While that incident wasn’t that much of a revelation, it made me think once again about topics I’d been mulling about for years. After all, the place where I found the relevant reference materials (after randomly flipping through many production books like a fool) was the key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. and design archives of a movie I’ve meant to write about for a while. Three years to be precise, as it recently hit its third anniversary. One that’s built around alternate forms of communication, where the feeling of touch isn’t so much a nice extra but a fundamental part of the experience. None other than Koe no Katachi, known as A Silent Voice overseas; since the latter isn’t the director’s choice of translation, let me go with the original title for once.

For those still unaware, Koe no Katachi revolves around Shouko Nishimiya, a deaf girl who was bullied throughout her childhood due to her condition, and Shouya Ishida, the most vocal abuser during the incidents we see, who found himself in kind of a parallel position after being scapegoated as the single culprit. The themes that the manga was so outspoken about (societal unpreparedness to deal with disability, the nonchalant cruelty of bullying and the tendency to blame an individual over addressing the community’s mentality) earned it critical appraise in its original form already. As far as I’m concerned, though, it’s Naoko Yamada‘s movie adaptation that refined it into a tale about people coming together to learn to love their own selves, as the necessary first step to address all those problems. If you haven’t seen the movie yet, I really encourage you to put aside a couple of hours for it. Not because I intend to spoil more than I’ve already said, but because the experience is worth it.

Despite the theatrical format limiting the adaptation somewhat, especially when it comes to the narrative’s scope, Yamada’s arrival to helm the project broadened Koe no Katachi‘s horizons. She strengthened ideas that were already present in the source material — especially those that are recurring motifs in her oeuvre, like the struggle to communicate — and as she’s been doing since Tamako Love Story, she proceeded to express them in a myriad of ways. In an attempt to make the viewers emphasize even more with Shouko, for example, Yamada went out of her way to obscure information from them. In a way, somewhat evening the field with a co-protagonist who struggles to keep up with conversations in a world that doesn’t do enough to help those that deviate from the norm.

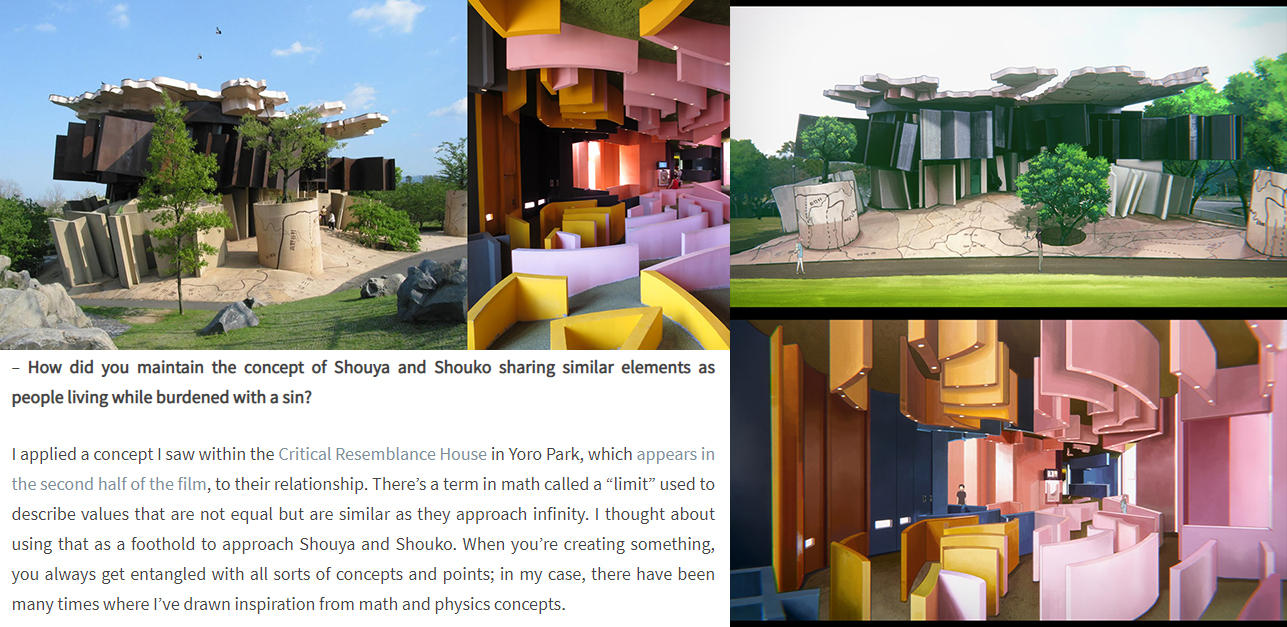

Some of those mechanisms were rather straightforward, like the direct reversal of Shouko’s situation by not verbalizing many of the sign language exchanges that happen in the movie; leaving most viewers up to the task of interpreting what’s being said, just like she often has to do in her daily life. Meanwhile, other decisions Yamada took in that same direction wound up being subtler. You’d have to dig out an interview to notice that she confirmed that the very extensive usage of flower language in the film had definite meanings besides their visual value… and then politely refused to reveal them, because making some information hard to read was part of the point. Even when it came to more standard directorial techniques like underlining the emotional distance between characters in a scene, she’d pull reliable old tricks like translating it into physical space in her compositions, then follow it up with totally unexpected mathematical concepts with a similar goal. With the passage of time, Yamada’s style has evolved towards emotional clarity, light — though also heavy — narratives, and truly boundless means to express those.

Regardless of the wide repertoire that Yamada proved to have, though, it’s still possible to narrow down all the nonverbal communication at the core of Koe no Katachi into two major categories. The first one’s of course that which relates to sound; its omnipresence in our lives but also its absence, as well as the constant motif of reverberations, which translate the sounds Shouko normally can’t hear into vibrations she can see and feel. And then we’ve got today’s subject matter: touch.

As a deaf person, Shouko’s communication is inescapably a more physical endeavor. Most daily interactions with her loved ones are done via sign language, manual articulations that require much more bodily involvement than making your vocal cords vibrate without even thinking about it. And, much like it conditioned her life, a demand of this caliber influenced the way Kyoto Animation approached the production. Those who are acquainted with the studio’s mentality know that cutting corners when it comes to the accuracy of their animation, even more so when it comes to a central theme of their works, is something they don’t even consider. In that quest for authenticity, KyoAni contacted various organizations — the Japanese Federation of the Deaf, the Tokyo Federation of the Deaf, and Sign Language Island — before enlisting many specialists to guide them; those included an overall sign language supervisor, various coordinators, multiple sign language models to perform the reference footage they needed, and even an expert in hearing-impaired speech to guide Shouko’s voice actress.

Following that, the movie’s core staff drew countless reference sheets for the sign language and general hand positioning, so that everyone at the studio knew how to handle the countless sequences that featured nonverbal communication — and when someone didn’t quite nail it, many specific hand corrections were issued by Yamada and the animation directors to address that. The level of nuance they aimed for, and eventually achieved, boggles the mind: well over two hours of carefully animated sign language usage, with a level of accuracy that isn’t simply “correct,” but rather reflects their confidence and proficiency in the language, while still integrating it to the regular character acting. You can tell someone’s mastered a tricky field when they’re capable of being believably wrong at it if they please.

And yet, as important as it was to approach the subject matter with the utmost respect, I feel like focusing just on the sign language doesn’t explain what makes Koe no Katachi such a tactile experience. After all, the realistic aftertaste it leaves doesn’t come down to the staff’s memorization of those hand gestures or even their true to life recreation, but rather how that set the tone for their animation effort throughout the entire movie; always reactive to contact, dense with secondary motion.

Admittedly, there’s a lot that goes into the creation of that feeling of tactility, and it extends way beyond the duties of the animator in charge of the scene. What does it entail, then, at least in cases like this movie? While it’s perfectly possible to have cartoony animation that comes across as reactive — squash & stretch is nothing but that principle taken to the extreme, often with amusing results — I believe that an important first step is establishing a believable, although not necessarily realistic, feeling of physical presence. That demands volumetric art with an attention to perspective by the animators of course, but the job of other departments (particularly the painting and special effects teams) can go a long way to reinforce that three-dimensionality. Following that, making sure that the three-dimensional animation feels responsive is just as important if not more so. This can place another heavy burden on the animator: making sure that the body reacts accordingly to the nature of not just whatever element it’s interacting to, but also according to its own. And once again, the surrounding departments can help them a great deal, especially the composite crew; in common everyday scenes, the illusion of real chalk writing or erasing a whiteboard can come down almost entirely to these digital magicians.

A fun way to check if all those elements clicked is what I’ve unimaginatively decided to call The Drink Test. Since anime in particular is essentially like one of those Stay Hydrated bots that have gained memetic traction nowadays, you’re bound to see characters having a drink many times throughout the run-time of whatever movie or series you choose to watch. And, jokes aside, examining how those scenes are depicted can tell you a lot about the tactility of any given work. Are they holding their drink properly, or were the staff forced to cut corners to the point that it just looks like it has merged with their hand? Does it feel like it’s taking into account its temperature, the texture of the container, and its weight? Beyond that, does the character’s body language feel distinctly their own while having a drink? Watching a single sequence likely won’t give you a definitive answer to all of that, but it’s the accumulation of moments like this that ultimately defines the tactility of a work.

Now I don’t think that Koe no Katachi has the most noteworthy drinking shots — OK I’m lying, this is iconic — but it does apply those principles to pretty much the whole film, marrying the studio’s technical expertise with a core theme of this work. Ever since Shouko’s arrival, before sign language is even introduced, communication with her is a tactile process. Noticing his carelessness, the teacher taps her on the shoulder, and the split-second animation conveys a gentle pressure that contrasts with his attitude. Shouko finds herself grabbing her bag in that authentically awkward way that we poor creatures beholden to physics know well. Her nervousness comes across through the paper creases, caused by her overly tight grip. The pages turn in a mesmerizingly real way. Shouko is, by all means, delivering her first words physically.

Following that same pattern, conflict is introduced in a tangible way. Shouya, like the complete fool he was as a child, decided to convey the discomfort he could feel surrounding Shouko in the way he felt she’d understand best: physical rejection. And Shouko eventually retaliated in kind. The scene where she snaps isn’t only important in the way it proves she’s not a detached, angelic being, it’s also one of the most deliberately uncomfortable scenes that KyoAni have ever put together, in no small part due to the extraordinary corporeal feeling of the animation during their brawl. That physicality remains a conspicuous part of the conflict right up to the last beats of the movie; palpable pain as he stumbles, and real muscle strain during his desperate struggle.

But of course, it’s not just negative feelings that are tied to the movie’s noticeable tactility. In Koe no Katachi, irreplaceable friendships are also forged via the feeling of touch. As the movie builds up towards its optimistic thesis — that by supporting each other we can learn to love not just ourselves but the world — we see more bonds being conveyed in that physical fashion. Right in the middle of the climax, in a scene so otherworldly that even the characters themselves think they might be in the midst of a dream, it’s again the genuine, soft feeling of touch that binds them together. Maintaining that tactility throughout such a long runtime isn’t just a technical feat, it becomes a thematic tentpole sustaining the whole film.

Again: the animation we watch isn’t real, sometimes not just in relation to us, but in regards to itself. And the fact that movies like Koe no Katachi are capable of making us forget that obvious truth and physically touch us speaks volumes of their quality.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

Donations to KyoAni have reached 2.6 billion yen at last count, or just over $24 million USD.

That’s an incredibly interesting read overall, especially in regards to the movie, but I have some trouble with the opening of your piece, Kevin. Animation indeed isn’t real, isn’t physical and isn’t usually single-layer… but, abstract as it is, it has its own set of strengths which shouldn’t be forgotten. As all visual media, it can use the same codes and elements (from colour to shot composition to visual metaphors to whatever), and as a temporal medium, it also plays with our ability to understand information organized in time. As an aside, call me a dumbass, but I feel that… Read more »

Thank you so much for the new material about KyoAni in general and Koe no Katachi in particular!

I love this discussion and interesting to hear your take on the crossroads that anime creators are dealing with in regards to using traditional pen and paper animation techniques versus moving towards all-digital animation.