Gekidan Inu Curry: Anime’s Fairy Tale Authors, A Collage Of Collages

Since the unique animation duo Gekidan Inu Curry have been entrusted with chief series direction and writing duties for the new Madoka Magica anime, we felt it was the time to explore their career at length: origins, influences, technique, and the way they craft twisted fairy tales that still evoke a childlike sense of wonder.

When talking about the state of studio SHAFT after a large number of creative and management staff members had left to other companies, we mentioned that they’d quietly decided to push back the anime adaptation of Magia Record: Puella Magi Madoka Magica Side Story – originally slated for 2019 and now due Winter 2020 – as part of that readjustment process. While we’ll never get tired of repeating that a delay is always preferable to the alternative, the most interesting reveal wasn’t actually that postponement, but rather a curious staff choice.

No, not the fact that Takashi Hashimoto is listed as action director (a sign that it’ll be very effects-focused? A bit of a misnomer perhaps?). We’re talking about the decision to entrust Doroinu of Gekidan Inu Curry with the chief series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario. and series composer roles. Chances are that the name of the troupe sounds familiar to most fans of the franchise, but whether you’re vaguely acquainted with them or are a big fan of their output, it’s still worth asking ourselves exactly what is Gekidan Inu Curry?

To be precise, though, the first question should be who are Gekidan Inu Curry? This unique duo of animators – in the broadest sense of the term – was united by similar aesthetic sensibilities and the explicit intent to reject the huge, heavily compartmentalized workflow we see in this industry at large, in favor of smaller canvases where each work would be their personal microcosm. And yet we’re still dealing with two different artists who arrived at that point following their own paths, and whose personal backgrounds influence what they contribute to Gekidan Inu Curry’s works.

The first member we’ll introduce is Ayumi Shiraishi aka 2White Dog (2白犬). For all we can talk about the troupe’s unconventional artistic chops, the truth is that she had a standard anime upbringing; after graduating from Yoani, Shiraishi joined studio Gainax in the early 00s. Though she did eventually contribute to some of their most iconic titles, she underwent most of her training in less celebrated franchises like Mahoromatic. But when you show as much promise as she did, you’re bound to gain everyone’s trust fast regardless of the canvas you used to express yourself, and that’s exactly what happened. By 06-07, Shiraishi was getting high-profile requests and even directorial opportunities not just with Gainax folks but all over the industry. Had she stayed in this more traditional path, Shiraishi would have undoubtedly become a household name anyway.

Shiraishi’s last standard animation contribution was in 2012’s A Letter to Momo… though there’s some trick to that; the movie was produced over a long time and director Hiroyuki Okiura recruited animators during the production of Dennou Coil in 2007, which appears to have included Shiraishi too. Regardless, he specifically highlighted her work in this scene and during the climax for its otherworldly qualities – and that’s saying a lot, considering the project gathered anime’s greatest animators.

In contrast to Shiraishi’s almost immediate success, Gekidan Inu Curry’s second member struggled more to make his anime career advance. Don’t get me wrong: Yousuke Anai, best known under the aforementioned pen name Doroinu (泥犬), technically did manage to land a job in the industry as well. For a few years, he held a position as digital painter and occasionally as special effects artist at subcontracting studio TANTO, without much of an opportunity to climb up the ladder. If that doesn’t sound very glamorous, it’s because it’s not.

In fact, it quite literally was a dead-end job, seeing how TANTO closed down its doors forever in 2007. Finding himself in such an awkward position, it’s not much of a surprise that Anai would turn back to his old colleague Shiraishi to go on an exciting independent journey instead. Though they’ve publicly stated that the reason that led them to found Gekidan Inu Curry was their shared artistic aspirations, considering Anai’s impending doom at the time and the sort-of-managerial position he’s always held in the group, it doesn’t seem much of a stretch to conclude that he was the driving force in the creation of the group for pragmatic reasons as well – not like that makes their creative goals any less true!

So, what was this duo capable of? It didn’t take long for animation fans to get an answer to that question. History goes as follows: voice actress and singer Maaya Sakamoto happened to see some Gekidan Inu Curry drawings for amimo LLP’s discontinued service DecoBlog, which she fancied so much that it quickly led to the production of a music video for her song Universe. And thus, after sharing some teasers, the short film was first released as an extra feature on Sakamoto’s concept album 30Minutes Night Flight, back on March 21, 2007.

Rather than a timid first step, their animation debut turned out to be an unashamed showcase of their style, though with a more traditional approach to the 2D animation than we’d later see from them – hardly a problem considering they were assisted by the likes of Yoh Yoshinari, Futoshi Suzuki, and Shinji Suetomi. The duo picked up on the themes that Sakamoto wanted to convey with her song, and according to the singer herself, expressed them more eloquently than she did. The universe may often appear vast and solitary, but as the music video argues when it reaches its climax, looking inwards can be the catalyst to realize we’ve always had people by our side and meetings that should be treasured. The joyful dancing that conveys that feeling still remains some of the troupe’s most evocative work.

But rather than the message in and of itself, what audiences found fascinating was the way Gekidan Inu Curry chose to convey it. The aesthetic on display there quickly became their trademark: cute fairy tale concepts that turn out to be much more twisted on closer inspection, a combination of standard 2D animation using paper with all sorts of stop-motion techniques, and collages that similarly mix not just art styles but different materials altogether.

In cases where they contribute individual scenes to other people’s productions, the duo often chooses to have their work credited as a “(public) performance,” which sums up the Gekidan Inu Curry experience elegantly; there’s a very physical aspect to their craft – making a plushie can be part of their regular workflow – that makes it feel more like you’ve been invited to their private exhibition than like you’re watching anime. An unconventional approach you won’t see much in the anime industry, but as we’ll see, it’s not as if they conjured a new style out of nowhere. If anything, the two wear their influences on their sleeve.

As a side note, we can look at the opening for the Nintendo DS Children of Mana game (2006) as a Gekidan Inu Curry prologue of sorts: directed, storyboarded, designed, and partially animated by Shiraishi, with Anai as assistant director, and produced at I.G under the same person who managed Universe.

When prompted about those influences, Gekidan Inu Curry have always given variations on the same answer. By digging around a bit, you’ll also find that Doroinu specified that as far as Japanese creators go, the classic animation series Manga Nihon Mukashibanashi was a formative experience for him; rather than the influence manifesting itself through a specific stylistic quirk, what he seemed to have absorbed from the series was the idea that animation is boundless, as the TV show was notorious for featuring as many aesthetics as folk tales it had to tell.

That said, the default answer of the troupe is that it’s a deep appreciation of Russian and Czech animation that brought them together in the first place, with more emphasis on the latter. Even without this context, the influence of classic Czech puppet animation on Gekidan Inu Curry‘s works is so thick that you might be able to deduce they watched an ungodly amount of animation by the likes of Jiří Trnka before they became animators themselves.

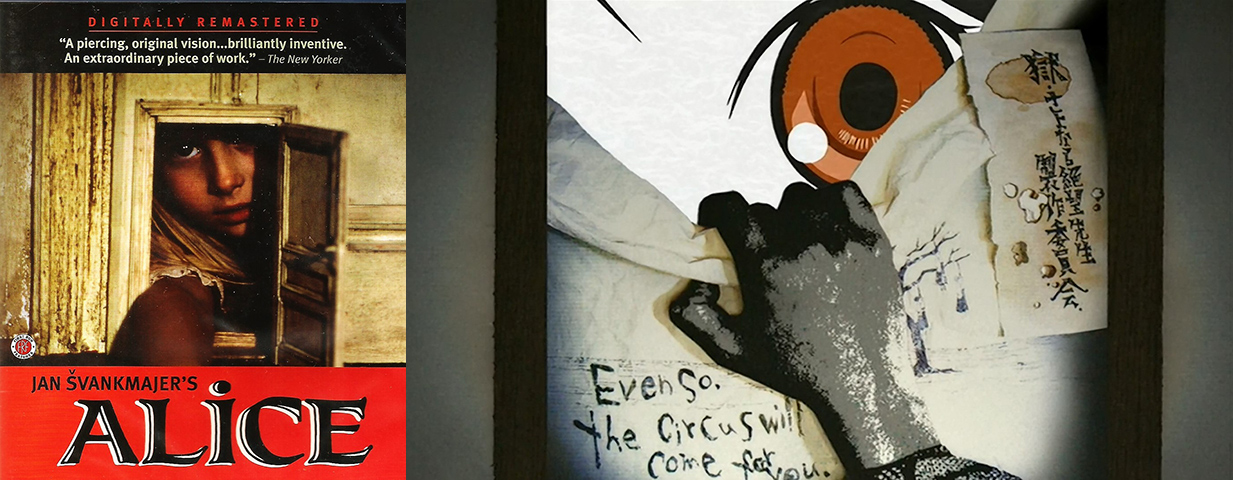

Although I don’t believe they’ve ever given a specific name when it comes to those otherwise obvious influences, if I had to narrow it down to one main culprit I’d go with Czech filmmaker Jan Švankmajer. There are many shared characteristics between their works, on both superficial and thematic levels. For starters, there’s the aforementioned twisted take on fairy tales that makes them more unsettling without compromising the childlike wonder they were meant to evoke. Observing their works more closely, you’ll find endless parallels, from the role reversal between the organic and inorganic to cause discomfort, to the fundamental fear that holes can evoke. And when it comes to technique, be it their usage of puppetry (real and mimicry of it) or their general approach to stop motion, it’s also obvious where Gekidan Inu Curry have their roots as well.

You’ll often see people drawing parallels between Terry Gilliam’s irreverent Monty Python animations and Gekidan Inu Curry’s output, wondering if the latter were swayed by his works. As far as I can tell though, they only happened to arrive at a fairly similar place following Švankmajer steps by themselves – which proves how influential his works have been for multiple generations. In fact, Švankmajer is so inspirational that he’s also the reason why another exceptional anime creator pursued this path; as we’ve mentioned before, it was his 1988 film Alice that made Naoko Yamada start paying attention to animation. His weight in the worldwide animation landscape can’t be overstated.

We’ve gone over how this major debut work encapsulated their style and influences perfectly, but what about its effect on their career? Well, the truth is that went as well as it could have too. While they didn’t become massively popular overnight, they caught the eye of people looking for unique artwork, which helped them secure income a steady source of income – promotional illustrations, cover art and short clips for eclectic musicians, and so on. This also includes further work with Sakamoto, who was so happy about how Universe turned out that she kept requesting Gekidan Inu Curry illustrations for years. Once they did make it big, those requests expanded to art direction duties, higher profile guest illustrations, and even a series of exhibits, but what we’d like to focus on is how their career has kept intersecting with the anime industry.

As it turns out, Gekidan Inu Curry’s anime output follows such a clear pattern that we can classify it in three groups. One of them is almost purely anecdotal: they felt so indebted to Production IG for helping them a lot on Universe that they came to their aid a few times between the late 00s and early 10s. The most notable legacy from those collaborations is Usagi Drop’s ending, which maintains some of their edge to depict remnants of a traumatic childhood, but overall proves that they’re perfectly capable of putting together a bright and uplifting sequence as well.

The first major avenue of Gekidan Inu Curry anime collaborations bore fruit even before that, though, and for equally obvious reasons. Shiraishi, already under the name of 2White Dog, returned to Gainax once again to help with the typography work throughout Nia’s arc in Gurren Lagann. And, alongside her partner, they crafted the flashback to her childhood first seen in episode #11; stop-motion memories, shadows of the past, puppet-masters in charge of depicting the feelings of a girl treated as if she were a puppet by her own father.

Although brief when it comes to real screentime, their appearance was quite memorable. Not only were their techniques an excellent way to convey those feelings, the fact that Nia has the most colorful outward appearance in the entire series but carries distressing baggage upon closer inspection makes her a match made in heaven with Gekidan Inu Curry‘s style. And that’s why 3 years after the fact, they were brought on once again under the Gurren Lagann Parallel Works 2 umbrella to create a music video where both Nia and Simon fight to escape the nasty cycle they’re stuck in.

Let’s not kid anyone, though. If we’re talking about anime studios that Gekidan Inu Curry have worked with, the one name that will inevitably pop up in people’s minds is SHAFT. The studio was open to unconventional artists even if their qualities were closer to illustrational work than other companies, and if you add to that the fact that director Yukihiro Miyamoto was also an ex-classmate of them whom Doroinu was in very friendly terms with, then you’ll see that these collaborations were fated to be.

The first one happened as early as 2008, when Miyamoto was directing the Goku: Sayonara Zetsubou Sensei OVAs and turned to his old acquaintances to handle its openings. Both Gekidan Inu Curry members directed the sequences… or perhaps we should say remixed them, since their approach consisted of taking the already outrageous material and reshuffling it, adding crafted materials to give real texture to its madness, and taking their stop-motion collage approach further than ever. Miyamoto made them regular guests on the franchise after that, even allowing them to produce an entire 7 minutes skit in Zan: Sayonara Zetsubou Sensei. If you want an exceptional taste of it though, I’d recommend their full-length Bangai-hen opening; not only is it some of their coolest looking work, the fact that they gave amusing titles to all staff members and self-deprecatingly called their work “detuning” the opening sums up their place within the franchise.

Though it was that existing friendship which brought them to SHAFT in the first place, the compatibility between the two groups of creators led to many other directors at the studio requesting Gekidan Inu Curry – and Doroinu in particular – to work for them too. Be it special countdowns, ending sequences like those of Maria Holic and Nisekoi, minor design work on various titles, or one-off appearances, their work has been peppered all over SHAFT anime for quite a few years at this point; incidentally, I chose to highlight that March Comes in like a Lion scene not because it’s all that noteworthy per se, but because he bypassed NHK’s awful practice of not allowing other studio names in the shows they broadcast by crediting himself as Doroinu Anai in the TV broadcast. Take that, disrespectful TV regulations.

Though it was that existing friendship which brought them to SHAFT in the first place, the compatibility between the two groups of creators led to many other directors at the studio requesting Gekidan Inu Curry – and Doroinu in particular – to work for them too. Be it special countdowns, ending sequences like those of Maria Holic and Nisekoi, minor design work on various titles, or one-off appearances, their work has been peppered all over SHAFT anime for quite a few years at this point; incidentally, I chose to highlight that March Comes in like a Lion scene not because it’s all that noteworthy per se, but because he bypassed NHK’s awful practice of not allowing other studio names in the shows they broadcast by crediting himself as Doroinu Anai in the TV broadcast. Take that, disrespectful TV regulations.

Before we get to the one show that took them to the next level, I’d also like to add that I find it amusing how relatively overlooked their contributions to Bakemonogatari are, considering how massively successful the show was. It’s not as if their style didn’t fit Tatsuya Oishi’s approach – if anything, the lack of acknowledgment might be rooted in how well they matched. Gekidan Inu Curry are always deployed as a special weapon, to make certain scenes feel fundamentally different starting with how they’re crafted. And yet, when it came to Doroinu‘s appearances in Bakemonogatari, they almost felt par for the course, like a natural extension of Oishi’s repertoire. Not only does Oishi teach his audience to expect wild stylistic shifts at any moment, he also happens to have dabbled with the inclusion of real footage, stop-motion techniques, and all sorts of collage compositions in his anime for longer than Gekidan Inu Curry have been in this industry, hence why the usually (and deliberately) stark transition into the duo’s work didn’t catch as much attention here.

Regardless of that, Doroinu‘s work was as evocative as ever; from a close inspection of a cute character that reveals the tragedy they carry in their backpack to simply means to spice up exposition or one of the many long conversations in the show, his contributions to Bakemonogatari always achieved their goal in stylish ways. Thinking of little of a splash they made even compared to the duo’s work in more niche titles is amusing in retrospect, but also further proof of how incredible of a visual lexicon Oishi’s productions have.

While their background appearances in Bakemonogatari have been sort of forgotten, their more prominent role in SHAFT’s next mega-hit launched them into stardom. We didn’t want to stress out Gekidan Inu Curry’s work in Madoka Magica too much – if anything, this piece wanted to show that they’re more than “the quirky Madoka artists” and that they’d already developed that style before – but that doesn’t mean we intend to look down on their masterful work on the series. The troupe was approached at an early stage of preproduction, and once again under their friend Miyamoto, they were given lots of freedom to create something genuinely otherworldly. To this day, the franchise is still reaping the rewards from that decision.

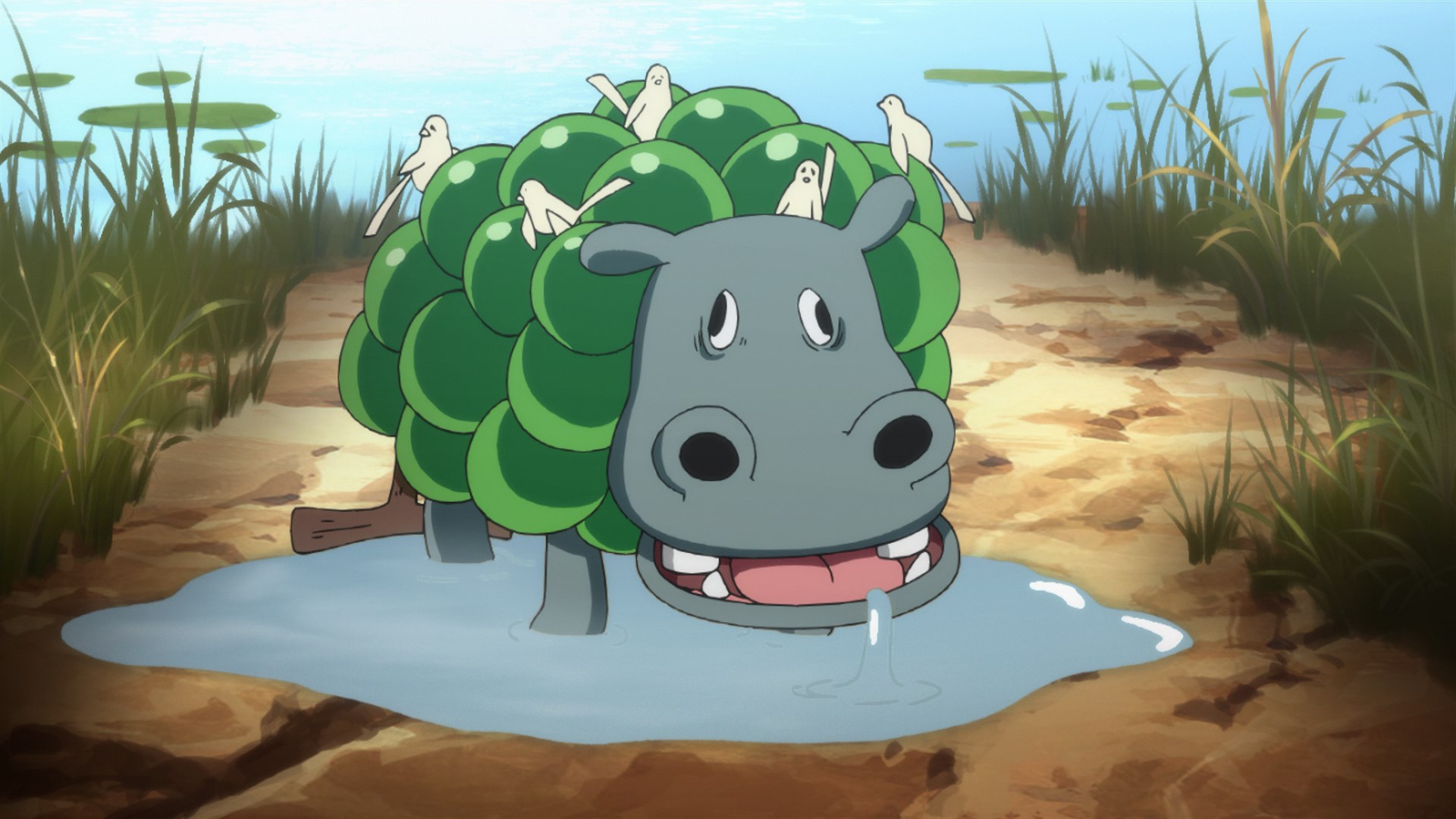

It’s no exaggeration to say that Gekidan Inu Curry are integral to Madoka Magica’s identity. The witches and their familiars they came up with feel as alien as the worlds they inhabit, equal parts mystifying and fundamentally repulsive. They’re as iconic as Ume Aoki’s sweet character designs, but with an even more important role that extends beyond standard concept art duties; as writer Gen Urobuchi himself admitted, he didn’t actually come up with the backstories for the witches, as that was all handled by Gekidan Inu Curry themselves, who also had the authority to push for script changes when it came to the magical creatures they came up with.

That might sound outrageous, but keep in mind that Gekidan Inu Curry aren’t only borrowing fairy tale aesthetics: they are the authors of their own folklore, which includes writing it. Sakamoto, who deserves some credit when it comes to understanding this duo since she sort of scouted them, said that watching their designs gives you the impression that each character has a story behind them. And that’s because they do, even when the text isn’t directly presented to the audience. If you’re wondering how Doroinu ended up not just directing the new Madoka spinoff but also writing it, keep that in mind… as well as the fact that he was already writing the actual text for the game it’s based on anyway. The duo is multitalented, and not just when it comes to visual techniques.

So, does that mean that Magia Record: Puella Magi Madoka Magica Side Story will be a non-stop otherworldly parade that’ll take Gekidan Inu Curry’s work to the next level once again, like its predecessor did? Not necessarily. Their output on the series was always deliberately confined, and Doroinu himself has already tried to downplay his role somewhat, while noting that Miyamoto will remain by his side and that they’ll try to keep things cohesive with the Madoka that fans are used to.

But with that in mind, whether you’re a big fan of the franchise or someone who just happens to like how cool Gekidan Inu Curry’s work looks, seeing a unique duo like them receive even more trust is an undoubtedly positive thing for anime as a whole. With our expectations in check, we’re still excited to see how they’ll fare in this new position.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

Great read, I got really excited when I realized Gekidan Ino Curry were behind the incredible animation sequences in Madoka and Bakemono. Do you think we should be skeptical about the rest of the staff involved though? I know there was talks of a lot of previous staff leaving, but is it possible they could still contribute as freelancers?

As an add-on to this question since he was mentioned in the article, is Tatsuya Oishi still at Shaft and or is it known what he’s working on now that Kizumonogatari is finished?

When I asked someone at the studio about the people who’d left SHAFT I sent a list of names with Oishi in them and got a yes, so…

The rest of the staff list is very much “these are the people that we’ve got left” so I’ve tempered my expectations, but it’s got potential for sure. All the big names you might have seen thrown around as people who’ve left will not return anytime soon if ever, but once people picked up on the situation they started mixing them with other creators who weren’t even part of SHAFT and could very well show up again, so the panicking’s done kinda overboard.

Thank you for this article! A very interesting read. Too bad twitter decided to skip your post yesterday in my timeline… Either way, very interested to see what Doroinu would create as chief series director/series composer (also Oishi new project WHEN).

So much interesting info here, I am totally excited! Didn’t even know about the duo’s contribution to Gurren Lagann TV. I have been wondering why they did that clip from Parallel Works, and now it makes sense. It was a great pleasure to read this article, and I bet it has to be so for many others, who can not read it because of the language barrier. It’d be great if I could somehow share this feelings with my local community. However, I didn’t find any information about copyright and translation rules on this resource. I’d like to know if… Read more »

Feel free too! If anything, we’re happy when people do that – we put this kind of information and interpretations out there for people to read them, so making it available for more people is just helping that purpose. The only thing I’d ask is always leaving a link to the original article and a short note about it, but otherwise, no problem whatsoever!