Tengoku Daimakyou Production Notes: An Exceptional Adaptation Facing Exceptional Challenges

Tengoku Daimakyou is an exceptional series facing equally exceptional challenges. It’s got a production environment and an amalgamation of talent most anime would die for, but also the duty to tackle a fascinatingly weird post-apocalyptic story that is somehow both terrible dense and also mostly laid back in nature. One of a kind!

Creating anime for television makes an art of compromising. It’s known that resources are insufficient and that production schedules have done nothing but deteriorate—a twisted accomplishment, given how poor they were to begin with. This reality has molded, and continues to do so to this day, the way these works are created. At its best, striking creative currents have been born out of those limitations, making their shortcomings into strengths of their own; if corner-cutting is inevitable, then you might as well be artful about it, because that way you might stumble across new tools of expression. Be it the surge of effective drawing count modulation techniques, further emphasizing the staging, or more recent technological advancements that seek to marry efficiency with expression, anime does have a long history of weaponizing its weaknesses.

At its worst, though, the attempts to deal with these limitations can completely drain the life away from these works. Whether it is insufficient or misdirected compromises leading to a shoddy title that collapses under its own ambition, or an overly conservative approach leaving nothing but a sterile product, the failure to navigate these circumstances is a common downfall for TV anime. On the flip side, that should mean that given the right personnel, a high-profile production environment, and an ample schedule, a project shouldn’t really have to face fundamental challenges—but is it really that simple?

Now, there is no denying that Tengoku Daimakyou is one lucky title. At first glance, its circumstances might not look exceptional, or even favorable for that matter. Hirotaka Mori is making his series direction debut, a position he only accepted because he was acquainted with animation producer Masashi Ohira; he was the person who happened to manage Mori’s episodes in Joker Game early into his directorial career, and they have since then often worked side by side in Production IG titles like PSYCHO-PASS and Moriarty the Patriot. For as memorable and distinct as Mori’s work was on the likes of 86 and 22/7, leading an entire project requires a different set of skills, so you can never take a smooth transition for granted.

Given that Ohira himself only has one previous title under his belt as an animation producer, this collective lack of experience could have put into question their ability to gather a competent team around them—so of course, they aced the job instead. Their positions happened to synergize well: Mori’s charismatic, elegant delivery had already earned the respect of many talented young freelancers he crossed paths with, while Ohira’s position in one of the most traditional animation powerhouses gave him access to a workforce with sturdy fundamentals. Between their deceptive immediate reach, and the gravity of projects that have already gathered many interesting creative minds, Tengoku Daimakyou’s team is as robust as any production can aspire to be. Full of up-and-coming talent and star veterans alike, many evocative storyboarders, and also the technical expertise to help those ambitious ideas actually land. In short, the complete package.

Of course, it helps that the other dreaded variable of TV anime has also been kind to Tengoku Daimakyou. While it was officially revealed in October 2022, there’s a reason why the existence of this adaptation was widely known before that: at that point, its animation process had been undergoing for a long time already, as the series was initially slated to air in April 2022—a whole year before its actual broadcast. Being allowed to miss the initial target date is common, and granting that extra time should never be considered a benevolent gift that solves all deadline-related stress, but the ample room and the possibility to keep a capable core team together in the long run does make this project’s background rather exceptional. After all, time can be of little use if all resources and talent are funneled away, but Tengoku Daimakyou’s team has diligently chipped at their workload until they’ve achieved something that feels fully realized. That extra time has also played nicely with its star guests, who have ended up contributing more extensively than they were due to; be it by drawing some stunning animation in addition to the storyboards, or by leaving behind meticulously detailed instructions. We can see instances of this at play in these early episodes, and more await us in upcoming weeks.

So again, if Tengoku Daimakyou doesn’t have to worry about the biggest issues that plague TV anime, could there really be another fundamental challenge for this adaptation to face? The truth is that scrappy planning and lacking resources aren’t the only inescapable headaches in such projects—in fact, some are actually more implicit in the format. Although it’s so normalized that viewers rarely ever question it, the fixed length of episodes and their number having to conform to seasonal programming can be kind of a nightmare from a storytelling perspective. Most formats have their own loosely defined runtimes that they can realistically get away with, but hardly any are set in stone as uncaringly as TV. Every second within one 30-minute chunk has a predetermined purpose the second your project heads for TV. You’re getting no more, no less, unless you fight tooth and nail for it; there is a reason why teams will opt for special broadcasts when given the opportunity, even though those tend to entail a larger workload. Similarly, the increasing commodification of anime has made it so much harder to get more than one cour greenlit at a time, because the industry needs to keep pumping out New Content.

Of course, none of those issues are unique to Tengoku Daimakyou—they’re systemic woes, and hardly the most pressing ones when it comes to your average project. However, this is not a standard TV anime, and the way all these variables interact is what ends up turning this adaptation into an exceptional challenge. The last point we need to consider in this equation is Tengoku Daimakyou itself: a series that is both terribly dense but also often lax in nature, an inherently contradictory core that director Mori found impressive as the manga is able to present it without friction.

Mori found himself dealing with a multithreaded thriller supported by obsessive planning across long arcs, though also one that happens to star two goofballs who enjoy screwing around the post-apocalypse. Its two major storylines intertwine in very deliberate ways, doing so to clue you in as often as they do to misdirect you. In turn, that makes the structure of the series itself part of that heavenly delusion. Tengoku Daimakyou is a formal achievement in storytelling that might take you by surprise if you happen to only recognize Masakazu Ishiguro’s name from his admittedly amusing maid-themed series, but it’s precisely that which makes it a royal pain in the ass to adapt. This team has the tools and support that most of their peers wish they did, but at the same time, their tricky assignment also happens to be more at odds with the structural restrictions of TV, precisely in a series that shines in that regard. To see how these issues and this team’s ingenuous solutions manifest, let’s finally delve into the first few episodes of the show.

For those who weren’t acquainted with Tengoku Daimakyou yet, the first episode makes it clear that this series is split into two major storylines: the adventures of Maru and Kiruko in the post-apocalyptic wilderness, and the mysterious plot in a highly advanced orphanage, centered around a Maru lookalike by the name of Tokio. Ishiguro goes back and forth between each thread, constantly finding ways to link the two; it can be a character passing out in one end and another one awakening in the other, a transition that implies physical continuity between the two, a shared theme, an implicit accusation, you name it. Its constant usage can make it come across as a cheeky gimmick, but while you can certainly imagine the author’s smirk behind some of these transitions, they do add a lot to the intrigue while also helping maintain an enjoyable brisk pacing.

The anime wastes no time to put this into practice—in fact, it does so faster than the original manga. While its first chapter was almost entirely dedicated to the kids in the mysterious institution, only dedicating one of those meaningful switches right at the end, the anime’s confident series compositionSeries Composition (シリーズ構成, Series Kousei): A key role given to the main writer of the series. They meet with the director (who technically still outranks them) and sometimes producers during preproduction to draft the concept of the series, come up with major events and decide to how pace it all. Not to be confused with individual scriptwriters (脚本, Kyakuhon) who generally have very little room for expression and only develop existing drafts – though of course, series composers do write scripts themselves. reshuffles all the early events and comes up with new points of connection. After Tokio is introduced to the concept of the outside of the outside, an almost unconceivable idea to someone who’s always lived inside the sealed world of this futuristic orphanage, a transition with many implications is made towards Maru and Kiruko. Similar switches happen multiple times in the first episode alone: some of them are the result of smart rearrangements, while others are essentially original, eventually leading to a new cliffhanger that would make the manga proud.

This team’s ability—and willingness—to mimic the author’s storytelling devices beyond just copying them shows their grasp of Tengoku Daimakyou’s grammar, and more importantly, it tells us that they get why that matters. Again, this was no easy job they were entrusted with. This season is due to adapt around 6 volumes of a very eventful, multilayered series. Simply speeding through them wouldn’t just do its carefully constructed mystery a disservice, it would also go against the entire point of the story.

In the midst of Tengoku Daimakyou’s intriguing, weird, and sometimes terribly cruel world, Maru and Kiruko genuinely have a great time adventuring together. They laugh, screw up, make bad yet upsettingly funny jokes, and convince themselves they’ve just invented seatbelts while being chased by a horrifying monster the size of a building; this last one won’t be covered in the anime, but allow me the slight spoiler to illustrate the point. The premise heavily codes the institution as the heaven the two co-leads have told to find, in contrast to the hellish reality of a barren post-apocalypse haunted by monsters. This is the one piece of civilization we see in a wrecked world, it contains hints supposedly related to their goal—like Maru’s lookalike Tokio, and why not, tasty tomatoes—and even Ishiguro own narration on the first page of the manga calls it heaven.

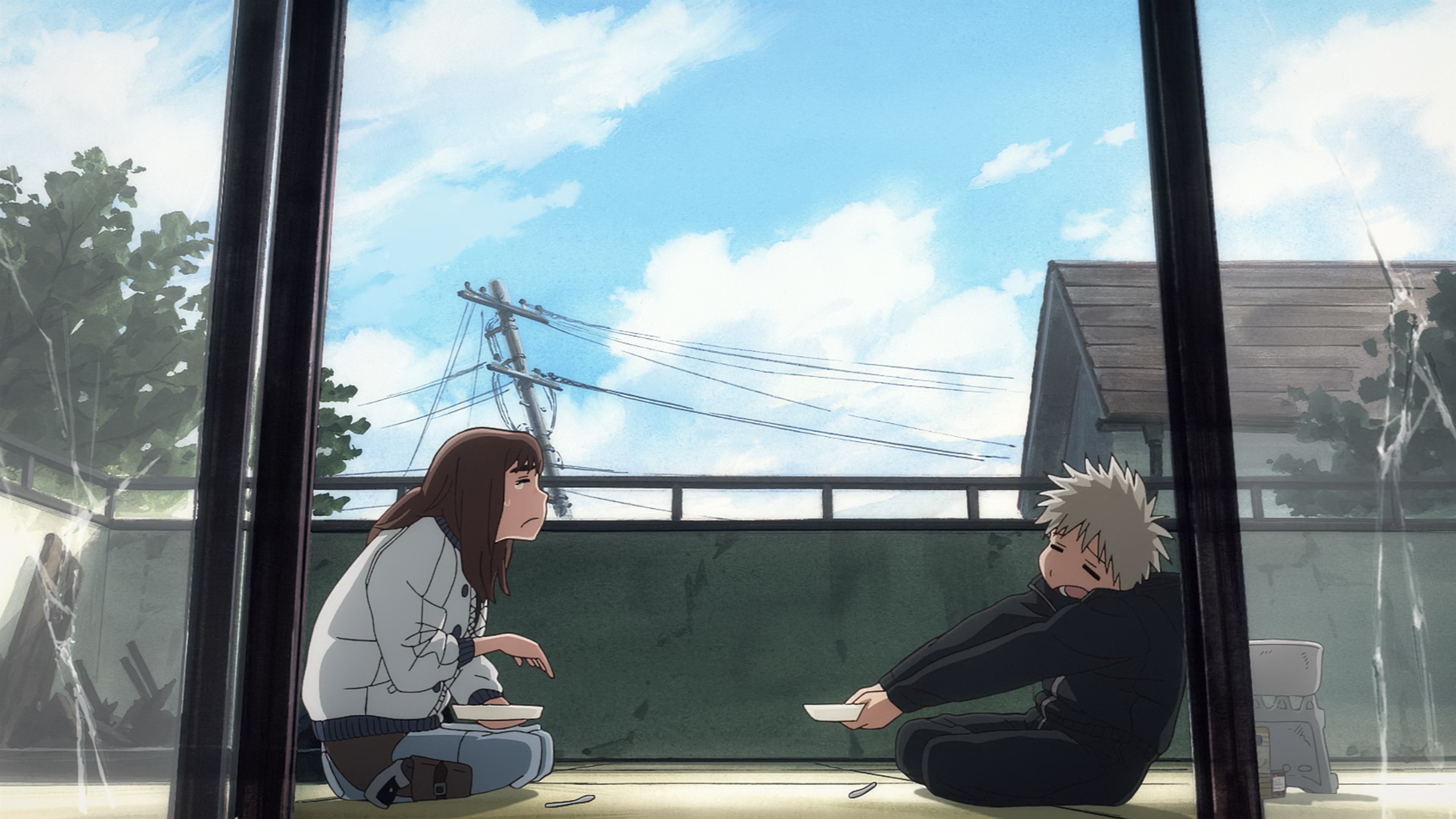

Despite all that, rather quickly we see that things aren’t as they appear. In the manga’s least surprising early twist, the obviously suspicious orphanage turns out to hide dark secrets. While Tokio’s side of the story has one unsettling reveal after the other, Maru and Kiruko’s quest across a desolate Japan is… frankly, more lighthearted. Things are never black and white in Tengoku Daimakyou, and tragedy soaks every thread in its story, but it still does make an explicit point that the closest thing we witness that is close to a heavenly time is these two’s adventures together. Even the characters themselves state as much—faster in the case of Maru, as the wife guy that he was born to be.

This is all to say that the seemingly inconsequential banter between the two actually is an irreplaceable part of it, if not the entire core of the story. Blazing through it, let alone entirely cutting it because it seemingly bears no narrative importance, would have led to a functional mystery with little of the original work’s charm and a decidedly shallower message. Through constant small rearrangements and calculated omissions, this team has taken a more burdensome path to pre-production, but also one that is more likely to translate Tengoku Daimakyou’s appeal. Mind you, this doesn’t mean some sacrifices aren’t being made. They have cut some endearing material between its two co-leads, and some of the countless hidden clues for that matter; the theme behind this piece is compromising after all. But by correctly identifying what makes Tengoku Daimakyou so appealing, and mostly making the right choices to address these inevitable pacing woes, Mori and his team have been able to maintain its spirit while focusing on the aspects that can make the anime into an experience that stands out on its own.

So, what are those aspects that Mori believes could elevate a Tengoku Daimakyou anime? In various interviews, the director repeatedly singled out a couple of them in particular. Out of all the elements that an anime adaptation is able to add, sound is something he found himself focusing on. A comic may not have audio, but any work with a distinct enough personality definitely feels like it has a sound of its own too—and to the director, the nonchalant off-kilterness of Ishiguro’s work was simply asking for a score by the one and only Kensuke Ushio. As a big fan of both, I absolutely agree with his comment about Ushio’s ethereal sounds being something you can just imagine playing across a school and a post-apocalyptic world alike.

Though he didn’t single it out in the same way as the sound, Mori did also list color and backgrounds as key aspects in reproducing the identity of a work. And just by taking one look at the first episode, it’s clear that Yuji Kaneko’s art direction plays a role as important as any other in depicting the world of Tengoku Daimakyou. The setting plays to strengths on display in past titles he’s worked with his studio Aoshashin, but framing this as typecasting for one very specific style does him a disservice. Over the last few years in particular, Kaneko has beautifully expanded his range; not just in what he depicts, but in the way he gets there as well, such as whether to emphasize analog or digital paintings. The grounded lived-in feeling of Josee and Ousama Ranking’s painterly, imaginative fairy tale represent two very different possibilities within Kaneko’s framework—and in Tengoku Daimakyou, another two distinct sides of him exist. A rusty, overgrown post-apocalypse and a clinical, sterile orphanage. Heaven and hell, whichever those may be.

In contrast to these aspects that are inherent to Tengoku Daimakyou‘s identity, the final point of focus in Mori’s approach had more to do with the adaptation itself: if they were going to turn this into animation, they might as well go all out with the action component of the series, since that’s something his crew had confidence on. The way they got around to highlighting it is rather interesting, since it’s not simply a case of gathering action animation aces as hired hands. Tengoku Daimakyou episodes with a major burst of action tend to set aside that entire scene so that a capable action animator storyboards it themselves, to either go ahead as the sole key animator for it too or to share it among their close acquaintances. We see as much in the very first episode, where the original action setpiece is storyboarded by none other than Tetsuya Takeuchi; it’s no secret that he’s disappointed about the general state of action in anime, since it doesn’t cater to his desire to match wuxia-like choreography with active camerawork, which makes it easier for smart directors to attract him under the promise that he can board the type of action he enjoys. The key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style., mostly provided by Takeuchi’s greatest follower Ryo Araki, lives up to Mori’s desire to use the action to spice up an already exciting offer.

Following Mori’s own efficient, elegant but ruthless direction in the first episode, the second one continues to make great use of the unique qualities of its format. This one comes by the hand of storyboarder Itsuki Tsuchigami and episode director Kai Shibata, the former being one of the notable guests who did more work than expected just because they were able to; which is to say that this very fun chase sequence is a nice freebie due to the project’s rarely positive scheduling shenanigans. The unsettling voyeuristic framing is enhanced in anime form, and cheeky directorial decisions like the switches to cinemascope enhance the tension in an inherently goofy way—very much in the spirit of this series. When it comes to that horror film-like sequence, though, it’s the awareness of the medium that I find most interesting. Both the manga and anime’s early stages exploit their portrayal of darkness in ways that simply couldn’t be copied over, which makes them valuable works on their own. The reveal of the bird monster in the manga is a brilliant little usage of negative space that comes naturally to a black and white format, something the anime had to approach differently. Meanwhile, this essentially original horror sequence in the anime is inherently tied to the concept of camera work and actual lighting; deliberately daringly so, as others have noted. By all means a series worth experiencing in both formats.

The horror vibes carry over to the third episode, directed and storyboarded by a good friend of this team in Kazuya Nomura. This time it’s body horror arriving in every possible flavor you may (not) want; grotesque, immersive imagery of a body being taken over, the indescribable terror of waking up in the wrong body, and even some hideous fish with humanoid parts that definitely do not belong in there. It’s arguably the most focused episode of the anime, and there are good reasons for that: Nomura’s very sleek storyboarding and the more comfortable pacing, as it adapted a shorter and more self-contained flashback. In a way, it’s a taste of what a truly uncompromised adaptation of Tengoku Daimakyou could have been—one that gets to retain all the flavor from the original and if anything makes it thicker, more impactful, even more characterful.

On its own, the events of this episode also highlight some of Tengoku Daimakyou‘s most appealing qualities. For one, there’s Ishiguro’s mastery at controlling information, which allows him to hide things in plain sight in ways that you can only appreciate in retrospect; it’s only after this episode that you begin getting details like Kiruko saying they’re a man in what seemed like a dumb gag in the first episode, the reaction to the reflection at the inn, the mysterious two year gap in the age they gave to Maru, or even the desync with the linework in Kiruko’s running. This is only the beginning of what can only be called completely maniacal foreshadowing on the author’s part, so I look forward to people cursing him when they realize every seemingly arbitrary point of information in the series was in fact massively relevant.

And if his carefully planned structure is interesting, so is the purely chaotic array of themes he decided to tackle—some executed way better than others, I have to say. This is something that Mori himself has stated should be maintained in the anime, as Ishiguro’s work allows you to approach them and have your own read; the director cited gender, technology, nature, and many more angles you could approach it from, none particularly more valid to him than the other. To me, Tengoku Daimakyou is a series that feels sympathetic to younger generations who have inherited a ruined world and receive nothing but scorn. Kiruko and Maru are derisively called part of the lawless generation, but it’s adults over and over who are behind the worst machinations of this post-apocalypse. It’s easy to spin this into a genuinely environmental read of the series, and certain conversations openly gesture in that direction… but at the same time, it is somewhat skeptical of communities flaunting that environmental flag. At the series’ worst, its desire to meddle into every delicate subject and taboo topic comes off as juvenile and pointlessly cruel, but for the most part, its deeply weird world and the many readings you can take away from it are a huge part of its appeal. Tomato weed heaven really did have it figured out, though.

In a way, it feels like with the passage of each episode, the series grows a bit more confident about skipping some content for the sake of tighter focus. Episode #04, directed and storyboarded by Takashi Otsuka, gets to emphasize the contrast between all the kids in the institution naturally seeking intimacy and their surveyors’ vigilant eyes by postponing or just removing scenes from the manga—and frankly, it’s all the better for it, as that also gave ampler room to Asuka Suzuki to take over the action part. Similarly, episode #05’s storyboarder Yojiro Arai even got to expand crucial memories further than the original, with stunning visual delivery at that. The final aspect that this episode gives me a great excuse to focus on, though, is the animation itself. It’s not the theologic intent behind yet another Takeuchi masterclass, nor his pupil Araki delivering the exact same satisfying flips, but rather the nostalgic art at the beginning of the episode that best exemplifies this show’s identity.

No one should be surprised to hear that Ishiguro is a big fan of Katsuhiro Otomo. So much so, that he makes a conscious effort not to make his own work resemble AKIRA too much; a message that the mobs at the start of episode #05 definitely didn’t get. It’s also no big reveal that Otomo-like forms are malleable, an inherent good fit for animation and a treat for a production filled with this many acting specialists. Multiple animators directly played off those qualities, and most interestingly, the opening itself does. Weilin Zhang‘s masterful intro is oozing with his own personality and worldview, but it’s arguably even more interesting in how it finds common ground between different eras of animation. The blobby forms in his animation are very reminiscent of the style Satoru Utsunomiya developed precisely after maturing on projects like AKIRA, which filtered through the likes of Norio Matsumoto and later Shingo Yamashita, ended up bleeding into popular webgenWebgen (web系): Popular term to refer to the mostly young digital animators that have been joining the professional anime industry as of late; their most notable artists started off gaining attention through gifs and fanmade animations online, hence web generation. It encompasses various waves of artists at this point so it's hardly one generation anymore, but the term has stuck. aesthetics. On its own, the opening already feels like a mix of old and new Yama traits, and if you started tracing all the inadvertent influences at play, you’d get a delightful mess of an artistry tree.

That said, I feel like there’s no point in trying to pin down Tengoku Daimakyou‘s animation to one specific current, as it makes a point to allow for variance. One of the greatest contributors to the show has been Shuto Enomoto, who stands out from all the aforementioned styles with his much sharper artwork. His sequences are still in conversation with Ishiguro’s work, but they do so on their own terms. This cute acting sequence from the first episode contrasts that sharpness that’s best used in tense moments with looser, cartoony expressions that feel like they come straight from the comic; in truth, they don’t really, but that speaks volumes of this team’s ability to make Ishiguro’s work into their own. And while on an artwork level Enomoto tends to contrast pretty strongly with his peers, we’re fortunate that he shares a passion for thorough articulation of the characters with a whole lot of animators in the team. We’ve gone over the well-known duo of Takeuchi and Araki, but perhaps the best surprise in this regard so far has been the appearance of Hiroyuki Yamashita to illustrate Kiruko’s living nightmare so vividly it hurts. Even when the animation isn’t outwardly flashy, there’s a consideration given to the acting that you’ll rarely find in TV anime.

And honestly, that makes sense. As we’ve gone over, Tengoku Daimakyou is no regular project. In some regards, it appears blessed to a degree that makes you wonder if that may actually be a deal with the devil at play. Its long, well-staffed production has paid dividends, and we’ve arguably yet to see the biggest names in the team. At the same time, this uniquely dense and somehow laid-back series takes clinical precision to reconstruct into a 1 cours anime without sacrificing the elements that make it special. Up till this point, the compromises have been reasonable, not only managing to capture most of the manga’s charm but also adding medium-specific appeal to the adaptation. So far, so good! If I know myself, see you again after episode #08.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

Fantastic post!

Kind of wondering if this is just going to be a single cour, given the content. Feels more like they’d need at least two split cours just to get the story across the way it’s being done. Not helped by how dragging the manga itself can be even without the flashbacks.

Unless they plan on cutting a few things in the process. Or decide to make it end on a cliffhanger. I don’t see them keeping this to just one season.

Regarding sound direction, it feels to me most anime (or any serie, honestly) rarely have a dedicated focus on it. Most of the time it seems to be just kinda there.

Not inherently bad, as anime should be more the a slideshow with great tunes. But the sound of a show tends to be more chiselled into my brain then its visuals.

Then again, it’s tricky to put this into numbers. Which percentage of shows do you think/guess put much focus on sound direction?

Impressive…Post? Article? It’s rare finding such through and mindful analysis in animaton… Wow