The Three Monogataris

In perfectly NisioisiN fashion, Monogatari has received closure in the form of the final entry of Endstory, which isn’t quite the end. The tale of Araragi’s adolescence definitely wrapped up however, and the anime itself seemed to be reflecting on the long 8 years journey that has taken us through 96 episodes and 3 films before returning where it all began. To understand all the changes it’s gone through, the best approach is to divide the series into three periods according to who the leading creative voice was, and explore how each of them approached the material. How has Monogatari evolved?

A vague description of what this series looks like might lead you to think that it’s a franchise with an unchanging aesthetic; you can always say that there’s a lot of text on-screen, rapidfire style switches abound, every now and then there’s over the top fanservice, the world is stylized and colorful yet an empty backdrop for the cast, and so on. Truth to be told though, its general appearance is exactly as consistent as its character designs: superficially the same, but fundamentally different upon closer inspection. This isn’t a purely visual matter either – if there is even such a thing as aesthetics dissociated from direction, but that’s another matter to discuss – as the approach of each director to the material they were bringing to life has been notoriously different. And that’s the point of this piece: a quick exploration of every Monogatari era, which unsurprisingly happen to be defined by the different series directors who have been entrusted with the series.

Oishimonogatari

Tatsuya Oishi is the favorite SHAFT director of right about everyone who is aware that Tatsuya Oishi exists, and there’s good reason for that. Once you learn that Akiyuki Shinbo is more of a mentor figure for the studio as a whole rather than someone undertaking standard directional roles, it doesn’t take much to realize that Oishi has consistently been behind their most interesting projects. SHAFT’s more experimental phase during mid to late 00s had him as the central figure, and many of the studio’s established quirks nowadays are watered down versions of his techniques. Out of all members in the Team Shinbo who successfully brought a revolution to SHAFT, his approach was consistently the most unique. And that provided Monogatari with a very wide visual vocabulary ever since its inception.

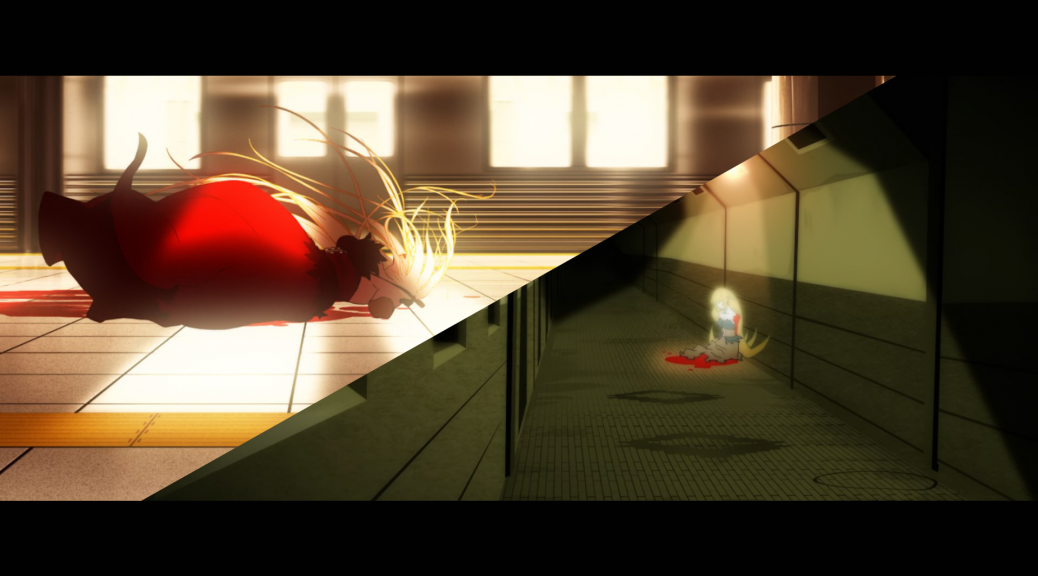

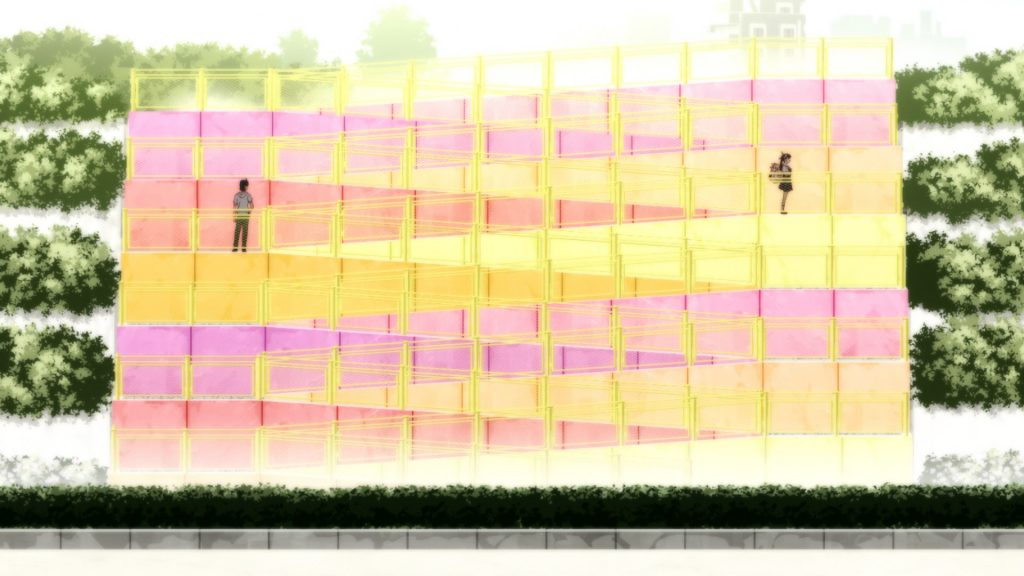

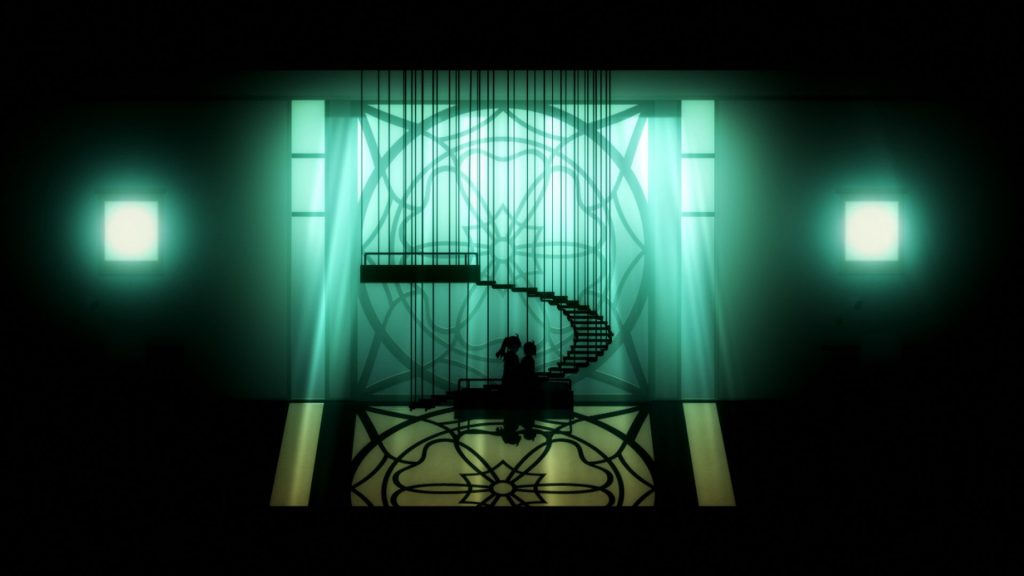

The show made it evident that the most consistent element in its presentation was the lack of consistency. This isn’t to say that there aren’t recognizable trends, but one of Oishi’s greatest assets is the ability to always reinvent himself; it’s easy to isolate techniques that he’s fond of, but their application changes every single time. All sorts of reality-based footage might be used to heighten the uneasiness during scenes dealing with unpleasant matters, as well as to take a ridiculous gag to a different level. Sometimes, its aim may be an equally legitimate attempt to make long monologues more engaging. This madness was painted on a canvas that is by now easily recognizable by all fans: a world composed of superimposed, simple flat shapes and gradients. Silhouettes that insinuate a city exists but are content to leave it in scant detail, except when it wants to make a point about architecture in memorable settings. This isn’t an approach totally unlike from other projects at the studio, but there is a reason its screenshots are easy to tell apart from other SHAFT shows, even when they don’t feature characters.

Another point I feel is worth looking at is the typography, a field that Oishi has always been interested in. One major issue with adapting this series was that NisioisiN wouldn’t stop talking even if he were underwater with no breathing apparatus, so they were forced to liberally trim his novels. One of the ways to do so was presenting chunks of the text during the anime’s many interstitial shots. As anyone who has seen the show can attest however, Oishi didn’t really care whether you could read those or not. The barrage of passages from the novel right at the beginning of every Bakemonogatari episode, the instances where messages simply didn’t fit the screen, or the countless shots with beautifully arranged words made it obvious that Oishi was seeking the effect he could achieve through the presentation of text, while he wasn’t all that invested in making those tidbits of information easy to parse. In fact, those rapidfire introductions disappeared the moment he stopped directing the series, but let’s leave Tomoyuki Itamura’s fundamentally different approach to adapting NisioisiN for later.

What about the animation then? The term powerpoint presentation was memetically attached to Bakemonogatari, which – internet jokes aside – always felt like a bit of a sad way to write off a series that features some bursts of spectacular animation. Oishi embraces the limitations of TV anime by concentrating the animation in very precise points, while the rest gets away with its static presentation because of its unique, ever-changing look. This wasn’t done out of disdain of movement of course, as Oishi himself is, by Takeuchi’s admission, the best animator amongst the studio’s directors. I feel like Ryo Imamura’s and Genichirou Abe’s work in Bakemonogatari are without a doubt the strongest sequences in TV iterations of the franchise, and the willingness of those aces to follow Oishi to seemingly doomed projects show just how much they value him.

Incidentally, a friend of mine has also started putting together a series of posts documenting the different styles featured in this franchise, starting with Bakemonogatari. His approach is obviously different but I recommend checking out since he’s gathering interesting examples!

Itamuramonogatari

Tomoyuki Itamura’s story is one of mixed luck. The first full series he was entrusted with was the sequel to the TV anime with the highest average Blu-ray and DVD sales of all time, a record that is unlikely to ever be matched. And as much as he was acquainted with Bakemonogatari, not only replacing Tatsuya Oishi but making up for most of its core team leaving the production was frankly impossible. On the positive side, he had a safety net in the form of the general aesthetic he inherited, which was smartly designed and ensured he would never put together an outright disaster. But at the same time, giving him the exact same toolset did nothing but highlight the difference in skill between him and his predecessor. That’s the tricky situation he found himself in – highly unlikely to fail, yet impossible to succeed.

It’s blatantly obvious how further Monogatari productions became much more restrained. Itamura flat-out got rid of the most unique quirks that had shaped the series until that point. When compared to standard anime it’s still easy to claim that his Monogatari features varied artstyles, but we’re dealing with diversity on an entirely different level; the series still occasionally featured different types of drawings, sometimes even used to good effect, whereas the aftermath of Oishi’s craft could be spaghetti for the staff to eat. All his experimentation with real footage, mixing media, stop motion and the likes essentially disappeared. Monochromatic situations with accents were suddenly scarce, while more digital-feeling colorful spotlights became the norm. Itamura’s approach to the artificiality of the show’s presentation was definitely different, although losing Takeuchi’s grasp of staging hurt him big time. It’s important to note that the world itself was one of the most consistent elements; by maintaining setting and character designs to a degree, they ensured that it was still immediately recognizable by most fans as the same property, even if closer inspection indicated big changes. And so while Takeuchi left his active roles, he still remained credited for Production Design, as they kept on expanding the world but intended to keep it cohesive. You can still find some alterations – textured looks became more commonplace versus Bakemonogatari’s simple gradients, screen density decreased a bit – but it’s otherwise the same peculiar empty stage.

As if to counteract the losses, Itamura was blessed in some ways. The least expected one came from the animation department. With the departure of the stars that penned the highlights in Bakemonogatari like Ryo Imamura, while others like Genki Matsumoto assumed more modest roles, it was to be expected that there would be a general quality decrease in this regard as well. As it turns out though, Nisemonogatari was one of the most polished SHAFT TV productions – it only faced issues right at the end, which is quite the improvement compared to Bakemonogatari outright crashing halfway through! And it led to more than just an overall increase in the care they were able to put in the drawings. Guest animators of the caliber of Nozomu Abe, ryochimo and Masayuki Nonaka consistently provided solid work, while current digital animation stars like Tatsuro Kawano even had their animation debut on the project. At the same time, the already present sakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. superstar Hironori Tanaka was entrusted with the climactic sequences. It’s true that those didn’t pack the same charisma as the highlights in its predecessor, partly because Itamura doesn’t have the same grasp on animation as Oishi, but the interesting cuts were plentiful. Admittedly, this production stability didn’t last for long, but there’s no denying that it helped a newbie director who struggled to achieve the same impact as his genius senior.

Perhaps the most interesting difference isn’t how each director approaches the craft though, but rather how they tackled this work in particular. I don’t value faithfulness as a positive directional trait whatsoever, but I feel like Itamura’s decision to allow NisioisiN to speak clearly eventually paid off, as the most thematically satisfying arcs arrived and the writer’s ridiculous schemes were unveiled. In contrast to Oishi’s active transformation of the material, Itamura showcases almost religious reverence to NisioisiN’s text. At this point the aesthetic really does become a side dish, fancy window dressing that must never obscure the original work. It’s not as if Oishi was disrespectful to the source material, but this new era is defined by the original author more than the staff adapting it – or transporting it to a new format, such was the obsession to maintain it as it was. The intentional dissonance between the actions of the characters and whatever playful dialogue they’re having already started off during Bakemonogatari, but from Nisemonogatari and onwards it becomes a constantly recurring situation. The quick media references in the form of reaction shots and slapstick in general also grow more abundant and ridiculous by the arc; Itamura isn’t exactly coming up with new resources, but the balance was entirely rearranged to fit his more conservative vision. And again, the number one priority even during those ridiculous moments is to present the dialogue in an entertaining manner, never to distract the viewer away from it. In a way, Itamura’s early Monogatari felt like it just happened to be an anime, but wasn’t particularly attached to the idea of being one.

To be perfectly fair though, and this is where a general look at the series like this shows its shortcomings, the timid Itamura who handled Nisemonogatari isn’t the same one who is wrapping up the franchise by any stretch. His approach hasn’t fundamentally changed, but his directional sense has been cultivated throughout the years and his storyboards in particular have improved a lot. While his vision will always be more calculated than a natural genius like Oishi, he’s gradually refined his Yukihiro Miyamoto-esque tendencies to the point of becoming one of SHAFT’s most interesting individuals. I tend to point at Owarimonogatari’s first season as the moment where Itamura reached maturity, but there’s a case to be made about Hanamonogatari already fully realizing his vision of the series. As far as I’m concerned though, it was his depiction of Ougi that first stood out as a pure Itamura triumph. Her disregard for personal space and unnerving presence weren’t simple decoration, but rather the most eloquent description of her nature. Tomoyuki Itamura finally felt like a fully-fledged anime director.

But what SHAFT giveth, SHAFT taketh away. Despite Nisemonogatari’s unusually polished production saving Itamura in the first instance, that gradually became an issue when it came to his work; the state of the studio’s TV projects decayed, as their stars in all fields left the regular staff rotations to prepare theatrical endeavors or seemingly disappear. The quality of the animation took a massive nosedive it never recovered from after Nekomonogatari (Black), and by the very end of the series even the lineup of storyboarders and episode directors was quite lacking. This final-but-not-quite arc was overall a subpar, simply passable production where only Itamura’s episodes left an impression as an adaptation. We’ve come so far, for the good and the bad.

It’s also worth noting, although this is more of a curiosity than a huge event, that within his reign there was a single arc where Itamura relegated the series direction duties to someone else: Yuki Yase, who took over during Onimonogatari. Yase seemed like he might represent a breath of fresh air at SHAFT as he matured as a director outside the studio, but eventually it’s become obvious that whether by choice or not he fits comfortably within the mandatory brand. He still has his own share of tricks of course, like the striking use of reflections to portray inner conflict, but in the end he doesn’t depart much from the norm – and that includes his work in Monogatari. Out of all his mannerisms, his fondness of dissonant palettes seemed like the one that affected Onimonogatari the most, but I can’t say I’m a big fan of it. If we were to look at the positives however, it was thanks to his trust in the young Taiki Konno that we got one of the most memorable, unusual visual showcases in TV anime. You know, no big deal.

Oishimonogatari Returns

And so we end with the prologue, which marks the return of the brilliant Oishi. Time might as well have frozen in 2012, the year when the film was initially meant to be released; don’t take this as just my figure of speech, since it appears to be an actual joke amongst its staff. SHAFT’s questionable management, which even caused a year long delay for Takeuchi’s new film Fireworks that they didn’t really make public, doesn’t seem to be entirely at fault here. What happened then? Chances are we’ll never hear the full story, but I would point at Oishi’s ridiculous approach to this project if I had to find the culprit. He had always tried reduce NisioisiN’s verbosity while ultimately capturing the same effects, but with Kizumonogatari he took it to a whole new level; a novel that is presented as an endless stream of consciousness became a movie where no words were spoken for over 8 minutes yet not an ounce of nuance was stripped away. I consider the movie’s ability to make us inhabit the protagonist’s head second to no anime, but I’ll spare you an extensive exploration of the film as I already wrote about its first part that sets the tone for the whole series. Just consider these years we spent waiting the price to pay for the impossible movie that Oishi envisioned.

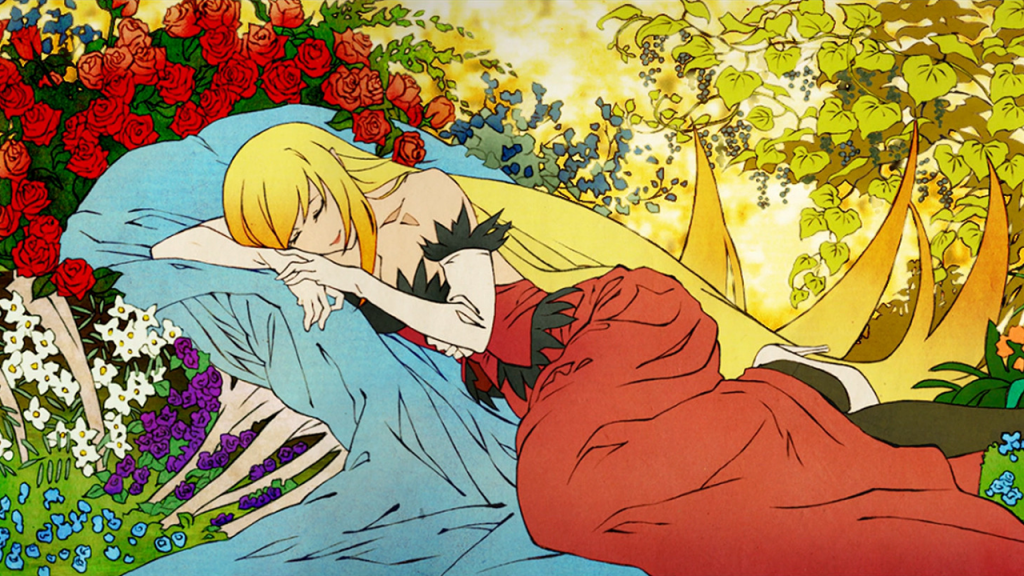

We’ve established his outrageous approach to the text, but how did he plan to depict it? When it comes to the visuals, Kizumonogatari is conceptually in line with Oishi’s oeuvre, but with the extra care a theatrical production allowed him to pour into it and then some. The format seems particularly fitting to boot, since his excellent editing sensibilities become more obvious when he’s putting together a film. His old mannerisms evolved in interesting ways; there’s the usage of pieces of real footage for example, which rather than being tied to viscerality took a more comedic role, leaving the depiction of gruesome aspects to stylized animation – something he admitted creators shy away from because it’s a pain, proving once again that he didn’t plan to make his own work easy! I would highlight his approach to the color as well, because the result is striking and his boldness hard to believe. Oishi didn’t hesitate to mute the palette of entire films to then dye them thematically – bloody red for the first one, the night’s blue for the second. He ended up with movies that felt believably colored rather than awkwardly soaked in warm/cold filters, while at the same time he enabled many of those accented monochrome shots that he loves. The more you inspect Kizumonogatari, the less sense it makes that it exists.

If we were to identify aspects that changed though, the clear choices would be the world and characters…which up until now had been the most consistent elements – I don’t believe this was intentional, but it’s amusing nonetheless. I consider the evolution of the designs a massive improvement, though also one that’s very easy to understand; Hideyuki Morioka, a trustworthy ally of Oishi, clearly intended to increase the inherent sensuality of the characters. In a movie series oozing with teenage and centuries-old-vampire hormones, sharper drawings and more accentuated silhouettes were a must. That said, the change I find most interesting is the world they inhabit (or don’t really inhabit, as per Monogatari tradition). While the regular series separates its characters from the setting by making the latter more stylized to the point that it’s barely defined, Kizumonogatari creates contrast by placing the cast in a photorealistic 3D scenery. This appears to be a bit of a point of contention in the fandom, but I feel like there’s an interesting synergy between it and the recurring textual feeling that those characters don’t really belong there. I suppose that it helps that I don’t find it aesthetically displeasing either!

I’ve left the look at the animation for last simply because there wasn’t much of a mystery in this regard. As you would expect, the greatest achievements in the entire franchise happened in the theatrical project that kept the studio’s stars busy for a long time. Ryo Imamura’s explosive pencil strokes justified his lowered output for years, as did every other heavyweight at the studio. And to be fair, it would be dishonest to imply that there were no surprises awaiting; from Yuya Geshi’s madness unbounded by form to Kou Yoshinari’s otherworldly depiction of vampires, as well as more delicate work by the likes of Yasuomi Umetsu, made the movies a non-stop showcase of delightful movement. Even Oishi directly benefited from this, as his brilliant staging of action, an asset he rarely got to use, was one of the highlights of the second film; the intricate setpiece that essentially involved Araragi being beaten around an entire building benefited from the kind of resources that the team would only have available on a movie produced over a long time. I suppose it’s appropriate to bring this look at Monogatari to an end with not only its peak, but easily the studio’s magnum opus as well. 8 years later I’m happily bidding goodbye to this ridiculously uneven, dear show that will still refuse to end after its ending.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

Excellent piece of writing, probably one of my favourite posts on the blog so far.

>photorealistic 3D scenery

wrong image here

Thanks for the heads up. One of these days I’ll master basic copypaste.

Also a small issue with the link for “Yasuomi Umetsu.”

Sometimes the site is just that excited to tell you to browse a certain link. Fixed!

“In a movie series oozing with teenage and centuries-old-vampire hormones”

This is a fantastic line. I had a good laugh.

It was just going to be teenage ones but then I realized Kiss Shot might be slightly too old to qualify.

“NisioisiN wouldn’t stop talking even if he were underwater with no breathing apparatus” might be my favorite description of NisioisiN I’ve seen yet

also, the link for the Umetsu’s Kizu cut is messed up, in that the URL is just a multiple repetition of the correct URL

I get away with the jabs because I’m a big fan of him to begin with…and because really, he /is/ in love with the sound of his words. Jokes aside though, it really is interesting to see how Oishi and Itamura have evolved towards opposite ends when it comes to dealing with Nisio’s writing. It’s easy to fantasize about Oishi handling the entire franchise instead but I’m actually glad we got to experience two takes that only diverged further the more time passed.

Your description of Itamuramonogatari as “just happening to be an anime” exactly encompasses my feelings watching Second Season. With some exceptions, it really did feel like the characters were performing a live reading of the novels in front of a nicely designed set. On the other hand, the source material of Second Season is easily my favorite in the series and I enjoyed hearing some of the best passages read out loud…

Exactly. For the most part it was a very satisfying picture drama, which only worked because it’s the moment where Monogatari starts reaping rewards for real and there’s a series of conceptually fascinating arcs. The franchise has been right about everywhere in the spectrum of interesting material to interesting adaptation…and often in a very unbalanced way.

Sorry to comment on an old post but I was wondering if there’s any news out there in terms of what Oishi is up to these days? I’m just really looking forward to more from him.

No problem! Unfortunately, there’s absolutely nothing on that front. Either Oishi has no project whatsoever, or it’s so early in planning stages that people behind the scenes aren’t really talking about it yet.

Just wanted to say there was a slight incorrection: Yase wasnt the only director to take on an arc, as Naoyuki Tatsuwa also ended up taking on Kabukimonogatari. Perhaps this has been corrected in other articles, however I felt it necessary to at least notate here in case it wasn’t