Maquia: When the Promised Flower Blooms / SayoAsa – Production Notes

Maquia: When the Promised Flower Blooms is one of the most powerful anime movies you’ll come across this year, and perhaps in general. Beautiful in many senses of the word, committed to its themes, and elevated by a once in a lifetime production effort that served to train both a fascinating new director and a studio as a whole.

Staff

Director, Script: Mari Okada

Core Director: Tadashi Hiramatsu

Assistant Director: Toshiya Shinohara

StoryboardStoryboard (絵コンテ, ekonte): The blueprints of animation. A series of usually simple drawings serving as anime's visual script, drawn on special sheets with fields for the animation cut number, notes for the staff and the matching lines of dialogue.: Toshiya Shinohara, Tadashi Hiramatsu, Masahiro Ando, Hiroshi Kobayashi, Naoyoshi Shiotani, Masaki Tachibana, Mari Okada

Unit Direction: Toshiya Shinohara, Tadashi Hiramatsu, Tatsuyuki Nagai, Heo Jong, Masakazu Hashimoto

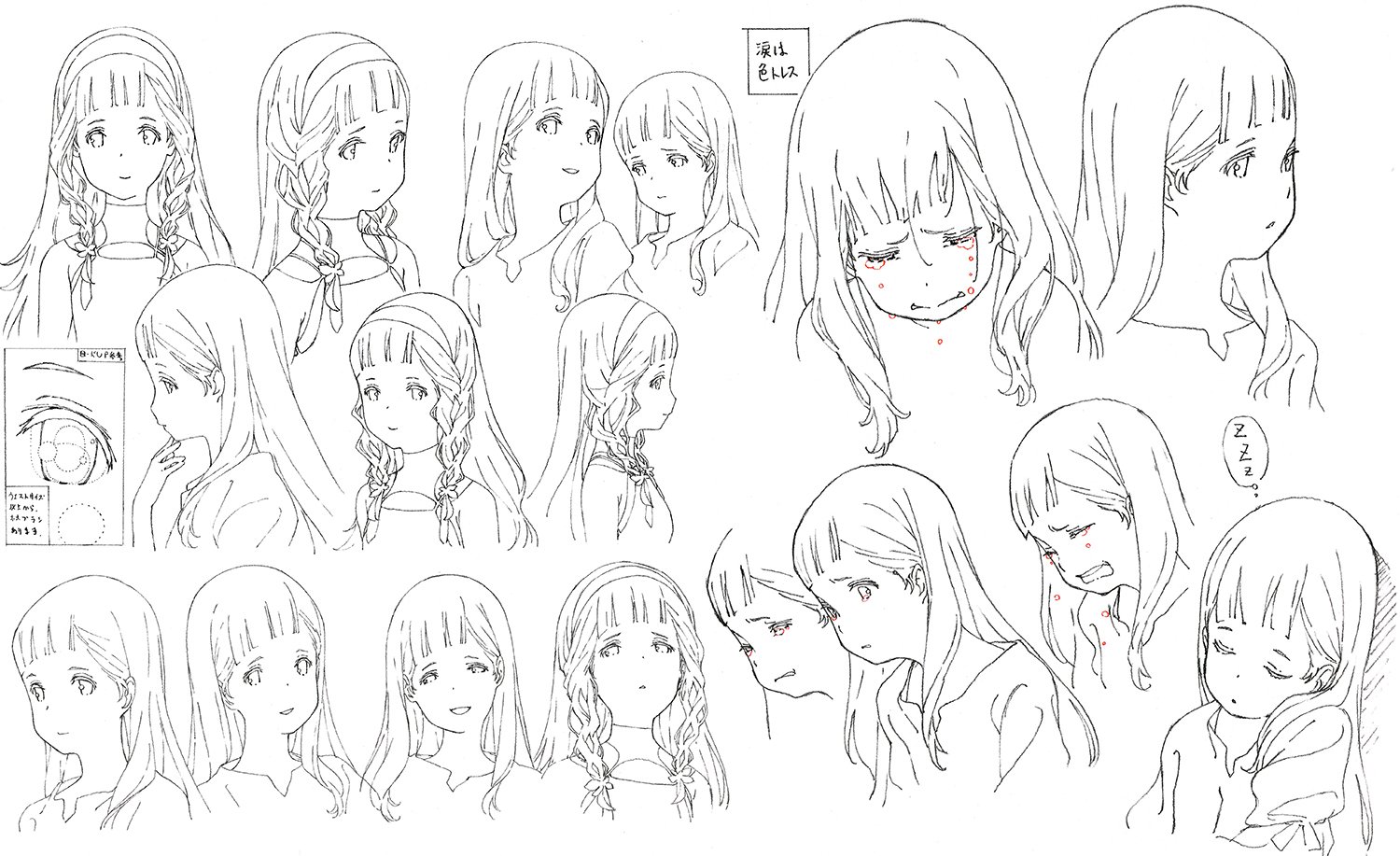

Character Designer, Chief Animation DirectorChief Animation Director (総作画監督, Sou Sakuga Kantoku): Often an overall credit that tends to be in the hands of the character designer, though as of late messy projects with multiple Chief ADs have increased in number; moreso than the regular animation directors, their job is to ensure the characters look like they're supposed to. Consistency is their goal, which they will enforce as much as they want (and can).: Yuriko Ishii

Main Animator: Toshiyuki Inoue

Animation DirectionAnimation Direction (作画監督, sakuga kantoku): The artists supervising the quality and consistency of the animation itself. They might correct cuts that deviate from the designs too much if they see it fit, but their job is mostly to ensure the motion is up to par while not looking too rough. Plenty of specialized Animation Direction roles exist – mecha, effects, creatures, all focused in one particular recurring element.: Yuriko Ishii, Toshiyuki Inoue, Noriko Ito, Kosuke Kawatsura

Assistant Animation Director: Masayoshi Tanaka, Nana Miura, Minako Shiba, Toshiyuki Inoue

Art DirectorArt Director (美術監督, bijutsu kantoku): The person in charge of the background art for the series. They draw many artboards that once approved by the series director serve as reference for the backgrounds throughout the series. Coordination within the art department is a must – setting and color designers must work together to craft a coherent world.: Kazuki Higashiji

Art/Concept Designer: Tomoaki Okada

PhotographyPhotography (撮影, Satsuei): The marriage of elements produced by different departments into a finished picture, involving filtering to make it more harmonious. A name inherited from the past, when cameras were actually used during this process. Director: Tomo Namiki

Key AnimationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style.: Toshiyuki Inoue

Kazuki Hoshino

Hidetsugu Ito, Takaaki Yamashita, Takeshi Honda, Masahiro Sato, Akira Honma, Fumie Imai, Ei Inoue, Hideki Takahashi, Ryosuke Tsuchiya, Akitsugu Hisagi, Akemi Hayashi, Hiroyuki Horiuchi, Yumi Ikeda, Izumi Seguchi, Asako Matsumura, Hidenori Matsubara, Nana Miura, Mino Matsumoto, Hisashi Eguchi, Yuuga Tokuno, Mami Takino, Yoshihiro Ishimoto, Tadashi Hiramatsu, Noriko Ito

P.A. Works

Kazuko Amano, Asami Hayakawa, Yurie Ohigashi, Asuka Kojima, Haruka Yamagata, Yuki Akiyama, Tsukasa Miyazaki, Yusuke Inoue, Yuka Miyoshi, Sayo Mizuno, Shibuki Watanabe, Aiko Natsuzumi, Yosuke Fukumoto, Hanako Murakami, Kohei Yano, Mari Tomita, Miki Nishikawa, Kanako Awada, Shinwa Kawatsura, Nemuyori Takase, Masayuki Yoshihara

A few months ago we wrote about Sayonara no Asa ni Yakusoku no Hana wo Kazaro aka Maquia: When the Promised Flower Blooms, and how the project fit in P.A. Works’ current plan to create a more welcoming workplace, with an environment that’d allow them to properly train young animators and encourage them to stick with their studio. Now that the film’s been released in blu-ray in Japan and has screened in multiple countries around the world, we’re back to give more context as to what that entailed, but also to unveil many of the secrets that made it into such a special experience. The movie isn’t without fault of course, but there’s a good reason it’s resonated so strongly with people all around the world. It sings the praises of mothers and their strength with the same unflinching voice that tells us of the visceral pains of motherhood. It humanizes the cast with some of the most evocative character animation that this industry has to offer, and it still has the energy to spare to depict spectacular action and an appropriately dense world. Maquia is thematically tight tale – for the most part – that’s brought to life through one of the most astonishing production efforts that anime’s ever mustered. And now it’s time to see how they achieved that.

When the project was first revealed in July 2017, Maquia immediately caught traction as the directorial debut of none other than Mari Okada. No matter how famous they are, seeing a scriptwriter move onto directorial duties is an extremely uncommon event, since the skillsets are simply that different. This is often summed up by talking about technical drawing skills, but that misrepresents the actual struggle; after all, the movie’s assistant director Toshiya Shinohara (referred to as the film’s father by Okada herself) also can’t draw all that well, and he readily admits his shortcomings in certain artistic fields. What he did have, however, is valuable experience. Most anime directors have a background in animation, hence why they’re capable of conceptualizing how the events should play out on a visual canvas. And among those who didn’t start by drawing their own scenes, the other common gateway into direction is production assistance: running around all departments involved in animation production, learning how to manage the process and perhaps absorbing the bits of knowledge to one day be able to head a project of their own, if they’ve got that predisposition. Any other path towards the director seat is quite rare, more so the farther the origin point is from hands-on animation manufacturing.

Possessing none of that, although often praised for her ability to detail her vision through the scripts, this was a tricky challenge for Okada. Fortunately, she had a spectacular team willing to follow her indications, plus quite the ample schedule to adjust to the role; it’s been about 5 years since P.A. Works’ president Kenji Horikawa pitched the idea of a “100% Okada work,” pre-production took over 3 years, and the actual animation process spanned from late 2016 until the last corrections and retakes in mid January 2018. Okada herself ranges from reluctant acceptance of that 100% herself qualificative to outright denying it, now more aware than ever of anime being as a team effort and of how integral certain staff members were to Maquia in particular, but there’s no doubt that she benefited from her position to deliver a story that in some levels feels like undiluted Okada. Even if they don’t necessarily exert it, a director always has veto power over a writer’s decisions, so she enjoyed the freedom – and heavy responsibility – of being able to stand by her ideas. If she keeps surrounding herself with crews as talented as this one, and considering her predisposition to learn about anime-specific toolsets, I believe she holds the potential to eventually stand on her own as a great director.

Maquia starts in stunning fashion, which sets the tone for a couple of hours of exquisite presentation. The themes of family and time are immediately interwoven, just like the hibiol cloth that the people of Iorph thread together. There’s an idyllic but also unsettlingly eternal quality to the scenery, conceptualized by designer Tomoaki Okada and then made into beautiful backgrounds by art director Kazuki Higashiji and his team; despite not being part of P.A. Works’ studio, the latter has historically been integral to the positive reputation of their works among the fandom, so there was no doubt he’d play a big role in their most ambitious project to date. Guided by the ideas of both Okadas, he ensured that this fantasy world felt somehow familiar to the audience, like a truly lived-in setting where the passage of time has tangible effects. Add to that the delicate lighting work and generally excellent composite, and you’ve got a movie that manages to be gorgeous even during its most peaceful downtime.

But if there’s someone whose visual presence dominates the film from the get-go, that’s living legend Toshiyuki Inoue, acting as the main animator. As the paragon of authentic acting, Inoue is the kind of artist who can singlehandedly make a difference, especially when he tackles a workload as massive as the one he had in Maquia. Details like the protagonist’s poor athletic form but also her resolve are elegantly conveyed through simple actions like walk cycles – not just to the audience but to the young animators they intended to train, hence why he also went out of his way to animate many short samples of those simple movement fundamentals to teach them the power those hold. And when things did get more hectic, be it in the many emotionally intense moments or during action frenzy, Inoue also stepped up to prove why he’s considered an all-time great in this field.

As we’d mentioned in the previous post about the movie, Inoue’s contributions aren’t just qualitatively impressive but also quantitatively so. He had a hand in 1/3 of the shots in Maquia, totaling around 400; he provided 180 cuts of animation that were rough in name only for young staff to polish them up and learn from him, 100 layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists. for other animators to flesh out, plus 120 cuts of completely finished key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style.. This madness starts from the very beginning: after joining the meetings in late 2016, Inoue began animating the movie since the very first shot, to the point that he conceptualized every single cut in the first 16 minutes until the title shows up. Most of that work was excellent animation that only needed clean-up, though some of the more demanding sequences he finished himself, and a handful he only drew the basics for others to elaborate – like the rendezvous between Leilia and Krim, key animated by Nana Miura. As a result of his thoroughness when depicting their emotions and daily life, the attack by the kingdom of Mezarte feels even more heart-wrenching. You can both thank and curse him for sharpening Okada’s knife.

Despite the generally positive environment and having managed to draw that much, Inoue actually walked away from the project a bit disappointed, because it was his intention to finish all those cuts by himself. Though as a viewer it’s hard to tell, the production had to cut some corners to stop the schedule from collapsing; Inoue himself said this was right about the most stressful job he’d ever tackled and that forced him to give up on full authorship of some sequences, while other scenes switched plans and ended up using 3DCG layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists. because otherwise the workload for the whole animation team was going to become unmanageable. But there still some scenes Inoue wouldn’t give up on no matter what, precisely because of how demanding they were. The first major example was the attack on Iorph village by the Renato, the rampaging dragons that Mezarte’s army foolishly tries to enslave. The panicking crowds, the debris and effects that accentuate the scale of destruction that weren’t even detailed in the storyboardStoryboard (絵コンテ, ekonte): The blueprints of animation. A series of usually simple drawings serving as anime's visual script, drawn on special sheets with fields for the animation cut number, notes for the staff and the matching lines of dialogue., Maquia’s own distress, even the fact that the creature is lashing out at the world out of the pain that its curse causes it more than directly targeting the protagonist – Inoue’s scene is so packed with fascinating details that new aspects will stick with you the more you rewatch it.

Unable to finish Inoue’s beastly scene with their in-house staff, P.A. Works had to contact their ex-member Yukiko Muroga (who had experience dealing with his intricate sequences) to draw all in-betweens for this sequence. It took her one month of drawing by herself, whereas Inoue key animated it in around 10 days.

Following that we’ve got a much quieter scene which if anything is even more important to the movie as a whole: Maquia coming across a baby held by its dead mother, and against the advice she received by her people and the mysterious traveler Barlow who was present in the scene, deciding to adopt the child as her own. There might be no better embodiment of the show’s themes than the protagonist being marveled by the strength of mothers even in death, as she shatters her rigor mortis fingers to free her baby, which she proceeds to hold with tenderness and resolution. Again, the gracefulness of the animation is key to the impact these moments have, and this segment features a fairly interesting relay of artists; we’ve young theatrical specialists like Ryosuke Tsuchiya (Maquia wandering through the woods until the child’s cries save her), Khara’s promising Yumi Ikeda (arriving into the tent), Production I.G-trained Izumi Seguchi (the scene afterward with the already iconic sunrise), but especially Takeshi Honda handling the powerful feelings at play during the trickiest parts. It’s worth noting that this is still all based on Inoue’s layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists. to varying degrees, so it has a certain je ne sais quoi that gives a cohesive feel to the acting throughout the entire movie.

Exceptional anime movies are more often than not either fully or majorly storyboarded by their chief director. This isn’t a requirement of course, but there’s a strong correlation between creators who have a very specific vision they want to uphold no matter what and films that end up being truly one of a kind; even notorious anomalies like Isao Takahata’s oeuvre aren’t as much of an exception as people seem to think, since he did give rough blueprints for the shots in his movies, which were praised for their striking composition sense by the animators who worked with him. The circumstances surrounding this project didn’t allow for that, however, so instead we’ve got a fairly large directorial crew handling bits and pieces with Okada’s ideas acting as the adhesive that keeps it all together. The next act of the film, storyboarded and supervised by assistant director Shinohara, proves that: while it’s not the most thrilling part by any stretch, the way he gives form to time, life’s finiteness, and the family themes that Okada envisioned ultimately makes it feel like another instrumental segment even beyond the narrative relevance.

Tight as the film is, some threads like Leilia’s feel a bit underbaked. Regardless, the intercalated scene where she asks the captive Renato why don’t they fly away is very poignant. Key animated by Inoue once again, as all sequences with hand-drawn creatures and animals are.

Maquia’s child Ariel grows up healthy, but after coming across a message that confirms her friend Leilia is still alive, she moves away from the farm that had welcomed them for years in an attempt to reconnect with her people. She quickly comes across other Iorphians who inform her that Leilia was captured as part of a ploy to absorb their race’s longevity into Mezarte’s royal bloodline. Their plan to rescue her involves sabotaging a parade, a scene that more than anything else is important because it showcases how important it was to let Inoue handle the animation of the dragon-like creatures – their wonky CGi rendition is hardly as imposing. This busy segment was storyboarded by Naoyoshi Shiotani of Psycho-Pass fame, and once again features many shots with roughs drawn by mister main animator. We do have another Inoue as a guest protagonist, though: it’s Ei Inoue this time who animates Maquia and Leilia meeting again.

The reveal that Leilia was forced to have the prince’s child thwarts the rescue plans, leaving Maquia alone and cornered. After lashing out to Ariel she finally comes to realize that motherhood is inherently a reciprocal relationship, one of the major points of the film, and a reason behind its universal relatability. Our next stop comes after a bit of a jump forward in time, with the two of them now living in the iron-forge city of Dorail. A new setting and a new protagonist when it comes to the production: Tadashi Hiramatsu, a major figure during Gainax’s golden age who’s been an irregular collaborator of P.A. Works ever since their Gainax-lite episode of Angel Beats. To put it plainly, Hiramatsu is versatility made into a human being – as you can tell by the fact that he juggled his myriad of jobs in this production while at the same time still working as Yuri!!! on ICE’s character designer and chief animation directorChief Animation Director (総作画監督, Sou Sakuga Kantoku): Often an overall credit that tends to be in the hands of the character designer, though as of late messy projects with multiple Chief ADs have increased in number; moreso than the regular animation directors, their job is to ensure the characters look like they're supposed to. Consistency is their goal, which they will enforce as much as they want (and can).. He was initially recruited for Maquia to draw the storyboards for the entire Dorail segment, but gradually that was extended to animation supervision, all sorts of designs, a ton of animation work, guidance for Okada and Shinohara, and so on. When it comes to the execution of Maquia, Hiramatsu was at the center of it all. And that’s how he ended up with his unusual title: Core Director.

Under Hiramatsu’s direction, the movie appears to grow in scale. The world is livelier than ever, more populated, expansive in spirit. This is exemplified by the very first scene, a bustling moment at the bar where Maquia’s now working, one of the livelier pieces of animation within realistic registers that I’ve had the pleasure to experience. Besides Hiramatsu’s concepts and corrections, there’s a name we must attach to this: Kazuki Hoshino, arguably the most important animator for this production behind Inoue and designer Yuriko Ishii – whose ethereal work is so beautiful I simply let it talk for itself. Hoshino does deserve some focus though, as he’s an overlooked figure among the famous creators involved here. It’s honestly no surprise that his name hasn’t caught on yet, since he hasn’t been around for all that long – he began training at studio Satelight less than a decade ago – and his commitment to movie projects is so time-consuming that he’s only been involved in about a dozen projects, often alongside Inoue like in this case. On top of that, Hoshino has the ability to become an “invisible animator”, to perfectly blend into the work no matter the tone or scale of his assignments. Hard to spot by the viewers, but a blessing for any team!

Hoshino originally joined the team alongside Inoue, and in his own way he had quite the impact on Maquia‘s production as well. Scenes as troublesome as that one earned him an honorary separate spot in the list of key animators, while his working methods influenced his peers; this movie was for the most part animated traditionally using paper sheets, but the presence at the studio of a younger artist who prefers digital looks like Hoshino doing such an outstanding job ended up making people curious. By the end of it, even the likes of Hiramatsu and Ishii were dipping their toes in digital animation, accepting it as a more efficient toolset for corrections and sequences where the analog production materials would be too unwieldy. So while his name doesn’t carry as much gravitas as the superstars who worked alongside him, he’s already the kind of artist who can pique the curiosity of the very best. Hoshino’s definitely poised to become a preeminent theatrical animator.

The next beats are defined by exceptional pieces of character animation depicting bitter emotions. Ariel’s frustration over the increasingly larger gap between his ageless mother and himself finally explodes after he gets drunk one day – his snapping animated by veteran Hidenori Matsubara and the fire by Inoue, in a scene full of Hiramatsu corrections. Ariel is forced to admit that he feels powerless because of their imbalanced relationship, unable to protect the one he loves the most. The sincerity allows them to part ways amicably enough as he goes off to join Mezarte’s army, but unfortunately she gets kidnapped by the contrived narrative. On a similar note of emotionally affecting scenes belonging to less graceful acts, Leilia’s torment continues as she retells how she saw her lover being slain by the royal guards. Rough around the edges as her arc can be, there are few sequences as emotionally loaded as her rejection of her current life by destroying all the jewelry she’s wearing (roughs by Hiramatsu, key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. by Inoue) and her furious lamentation. The latter is a bit of an animation ad-lib by Akemi Hayashi, who departed from the storyboardStoryboard (絵コンテ, ekonte): The blueprints of animation. A series of usually simple drawings serving as anime's visual script, drawn on special sheets with fields for the animation cut number, notes for the staff and the matching lines of dialogue. with a truly memorable series of cuts. Her dedication to authenticity was such that she went back and corrected the scene based on the voice acting, to make it into one of the greatest audiovisual encapsulations of what Maquia is like.

As far as I’m concerned, the movie finds itself in its messier acts at this point. For every scene that furthers the points that it’s been making all along, we’ve got a couple that go through the motions of what a fantasy flick is supposed to do here, diluting Maquia‘s precious essence a bit. On the one hand we’ve got moments like Ariel’s interactions with his pregnant wife – none other than Dita, the girl who teased him when they lived at the farm – which ties the themes of family and time again. These relationships evolve with the passage of time, and even the helpless child holds the potential to become a father. On the other hand, we’ve got a long war act that would be thrilling if it were in a movie that actually supports it. Though on the flipside, it’s a damn cool looking war, as all things in Maquia are. Hidetsugu Ito‘s dense effects and spectacular warfare, and Inoue’s long final meeting between Leilia and Krim are only a couple of the eye-catching scenes in this comparatively lower points of the film. Even lesser Maquia gives you plenty to appreciate.

Clips like this are the reason why Inoue receives calls to animate horses specifically.

The movie finds its footing again as it marches towards the end, starting with Dia’s childbirth shots masterfully intercalated between the climactic moments of the war. Besides its obvious thematic and narrative weight, this sequence holds extra importance from a production standpoint because it’s the moment that Mari Okada decided to storyboardStoryboard (絵コンテ, ekonte): The blueprints of animation. A series of usually simple drawings serving as anime's visual script, drawn on special sheets with fields for the animation cut number, notes for the staff and the matching lines of dialogue. herself. As you can tell by comparing her boards and the finished footage, this is the sequence they took the most liberties when interpreting the layouts, which confirms Okada approached this entire project willing to learn from animation artisans so that she can best tell her stories in this medium, rather than to impose her ideas in strict fashion. And as a side note, those amusingly Darlifra-esque shots aren’t misleading you – the animation supervisor for this scene was Masayoshi Tanaka.

After wrapping up Leilia’s arc as well as it possibly could, Maquia makes a final victory lap, one final emotional bomb that you knew was coming all along but that it easily earned. The final events in the movie are implicit in any story about asymmetrical relationships in regards to the passage of time, but when it comes to something as genuine and devoted to its ideas as Maquia, it hits harder than ever. Okada’s first venture into direction ends with the thesis that loving is still worth it, and that there can be ingredients other than sadness to goodbyes. Her main animator Toshiyuki Inoue also bid farewell to the project by saying that he struggled an immense amount, but that he’d love more movies like this. It’s too early to say whether P.A. Works’ training goals will be fulfilled – though the movie definitely gave their youngsters a chance to learn from freelance stars doing their very best – but what we know for a fact is that Maquia deserves to stand among the absolute strongest anime productions.

All things considered, I wouldn’t hesitate to agree with them. Maquia was worth it.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

i think this is not just the first anime i’ve seen where they let a mother give birth in some pose other than flat on her back (which is actually supposed to be one of the most difficult and painful childbirth poses!) but the first piece of fiction where i’ve seen that happen, EVER. the thought put into details like that and the incredibly thorough acting were really breathtaking to watch–though i agree that i personally would’ve liked to see more care and cohesiveness to leilia’s arc haha.

Things like the war and the time sorta wasted on the fantasy conflict feel like extraneous elements, but Leilia’s arc is more of a pity in a way since it definitely belongs in there but there’s only so much they could achieve with limited screentime. But yeah, at the end of the day the good vastly outweighs the bad!

Did anyone else feel like this was some kind of movie designed by Akihiki Yoshida, character designer of FF Tactics…? No, just me…? Okay… To me, everything felt very strong and building up until the end of the iron-forge city of Dorail act. The growing distance between mother and son, the darker aspects of immortality creeping in, the unsettling harassment on Maquia by Ariel’s coworkers and his powerlessness. Then, uhh…war, back to the original white designs, and jumping off a roof when you finally see your daughter. Ariel’s cry to Maquia for her not to leave him at the end… Read more »

Oh, and I forgot to pay my due respects to you, Kevin, for putting in the effort of writing such an extensive and informative writeup on the film. It’s so satisfying to be able to get to know more about the people behind this visual powerhouse of a movie, thank you so much!

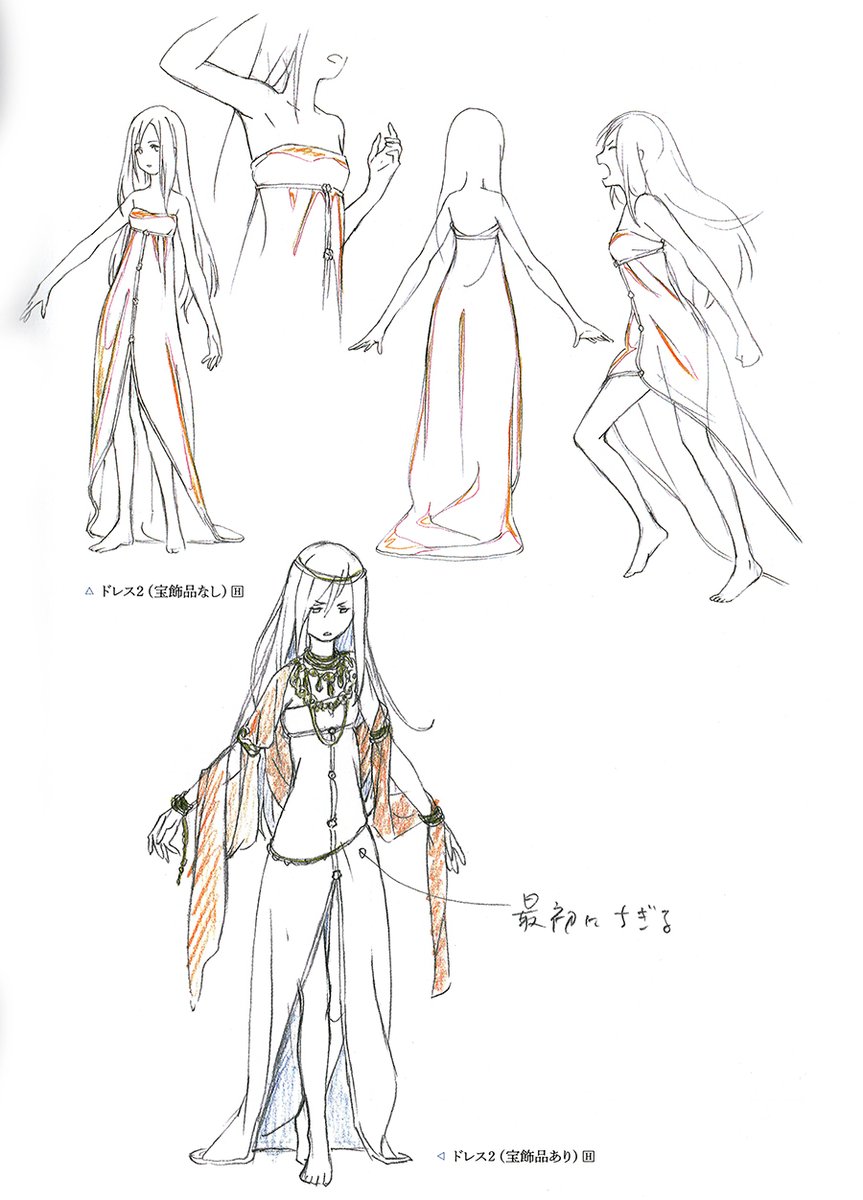

Yoshida drew the original designs! His concepts are actually my favorite fantasy element in the film and easily the best application of P.A. Works’ model of “get a popular illustrator to handle the drafts and promotional images to attract attention.” As for the rest: setting design fell for the most part on Tomoaki Okada’s hands – you can actually see his designs for both Dorail and the farm on the settei book they released. The precise detail got defined by the background art tea, though. And when it comes to outfits, it’s a hodgepodge. Yoshida, Ishii, even Inoue (for the… Read more »

Ohh I see. So cool to know Yoshida was involved in this! It really felt like a FF Tactics/Bravely Default feature film (with a convoluted story to go along with it just like in the games!). Thanks again for taking the time to answer.