Mobile Suit Gundam Hathaway’s Focused Excellence And The State Of 2D Mecha Anime

Mobile Suit Gundam Hathaway is shaping up to be an excellent film trilogy, a collective effort by creators who approach realism from their own angle coupled with stellar character acting—but how come such a high profile work by one of the remaining bastions of 2D mechanical animation went the 3D mecha route?

Mobile Suit Gundam Hathaway is the latest iteration of Sunrise Studio 1’s high-profile Gundam productions. A mere look at the synopsis will tell you that it’s not exactly the most welcoming starting point for Gundam‘s Universal Century timeline. Its conflict is a direct consequence of previous events, with the Federation having fallen into its oppressive habits yet again after the Second Neo Zeon War, and protagonist Hathaway Noa’s drive to lead the terrorist organization Mafty to confront them ultimately being the fact that he’s haunted by his actions during Char’s Counterattack… or more specifically, during the novelized take on those events by the name of Beltorchika’s Children. Hathaway’s character arc as a whole is more interesting with the knowledge that he was in a position to choose between Amuro and Char’s paths, and there are both cute small details and grander sociopolitical implications that you won’t catch if this is your first rodeo around UC.

If that’s scaring you away from what seemed like an otherwise cool trilogy of movies, you should consider another point: it doesn’t matter. The reason why Bandai and company feel confident in giving such high-profile treatment to these films, and why Netflix was also willing to snatch them for a whole lot of money for an international audience, is that Hathaway still works as a standalone story. Conflict in UC is by design cyclical, and cultural osmosis alone should have given you enough of a context to grasp the factions at play with the information the film supplies. At the end of the day, you shouldn’t really obsess about watching Gundam’s UC timeline the right way. If a flashy new entry gets you interested, feel free to start there; if you deem it interesting enough, then chances are that you’ll backtrack to watch all the previous series that gave it context, maybe even revisit that one starting point to reappreaciate it, and if you don’t you can just skip ahead of time itself and watch Turn A, because that never fails.

Watching order debates aside, it’s clear that the confidence placed on Hathaway oozes from the first film’s every pore. The choice of director in Shukou Murase might have looked like a risky bet, as he wasn’t exactly a hit-maker, but in the words of Gundam producer Naohiro Ogata himself, he was essentially the only option for what they had in mind.

Murase entered the industry through Nakamura Pro in the late 80s and has been involved with this franchise since he was in charge of the bombastic first few minutes of Mobile Suit Gundam F91, becoming a fairly regular contributor to it ever since. Over time, and especially with his transition towards a focus on directorial duties, Murase honed the realistic leanings into that specific style that Ogata sought: a gritty, dark and intricate approach to animation dipping its toes into his film noir influences, with compositions more reminiscent of live action and very threedimensional art built upon the abstract shapes of his complex shading. All of this, without forgetting his careful articulation of the characters’ demeanor. In short, the word cool made into animation. It felt like the one piece he was missing to achieve broader success was being entrusted with a solid hardboiled narrative for people to dig into—and that’s what Hathaway has provided, hence the unsurprising acclaim that this perfect match has earned.

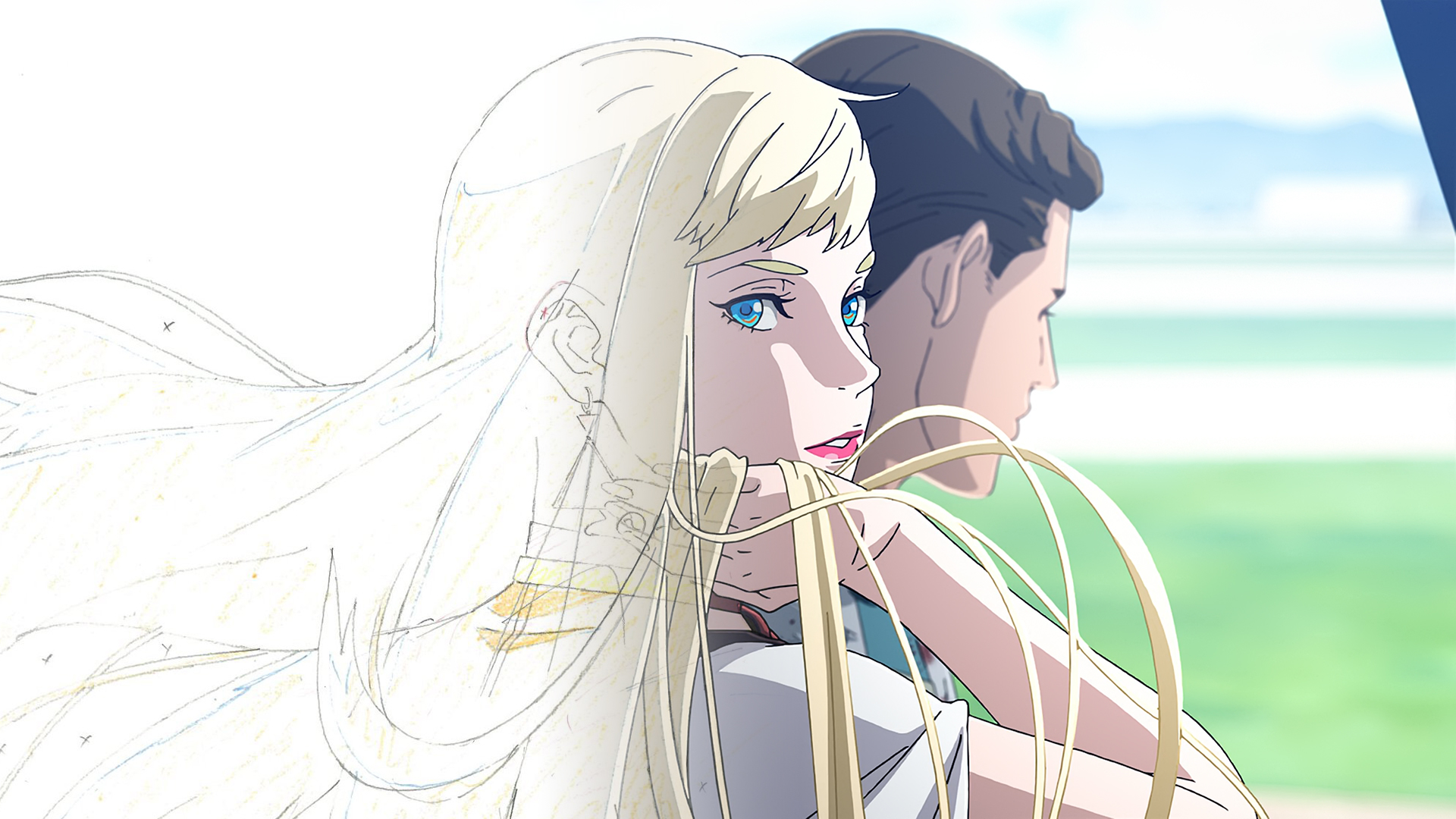

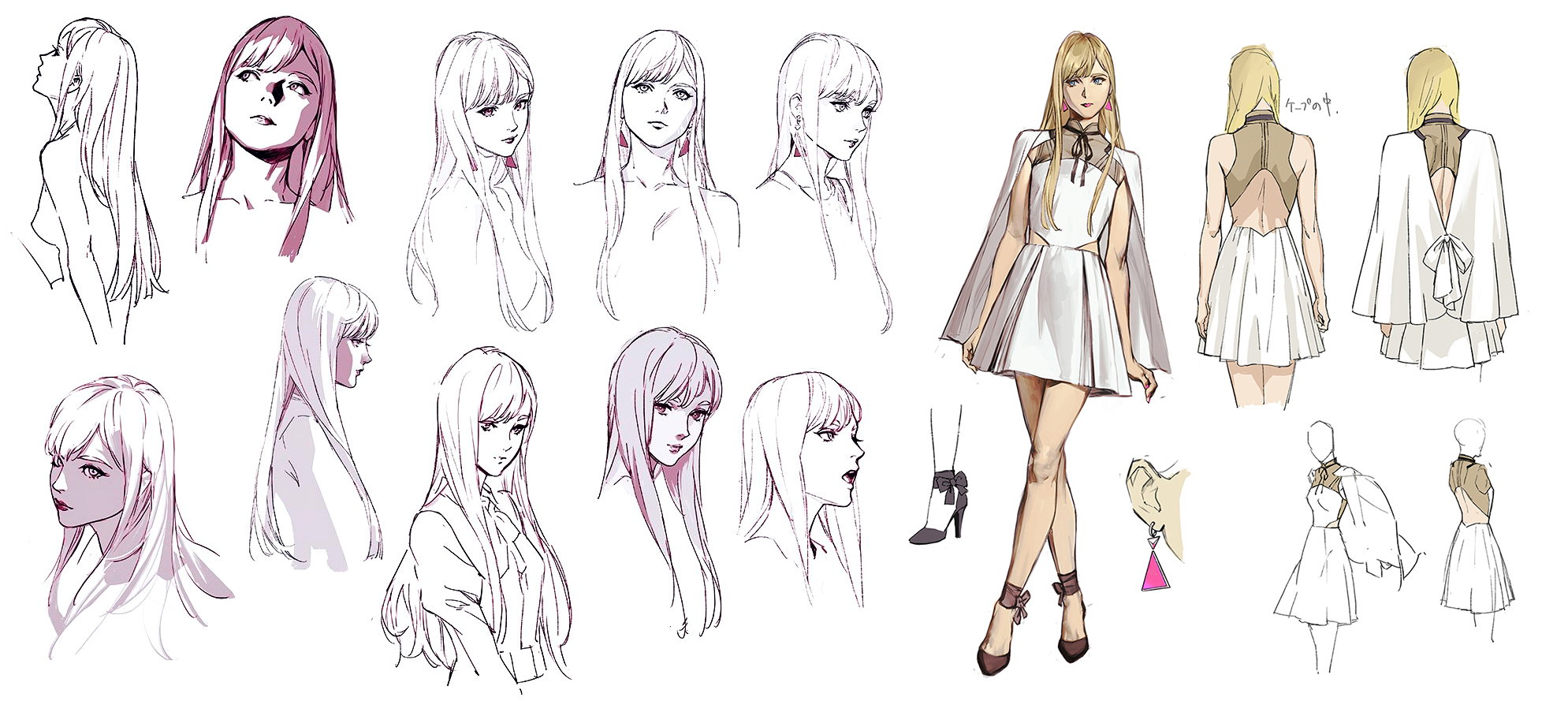

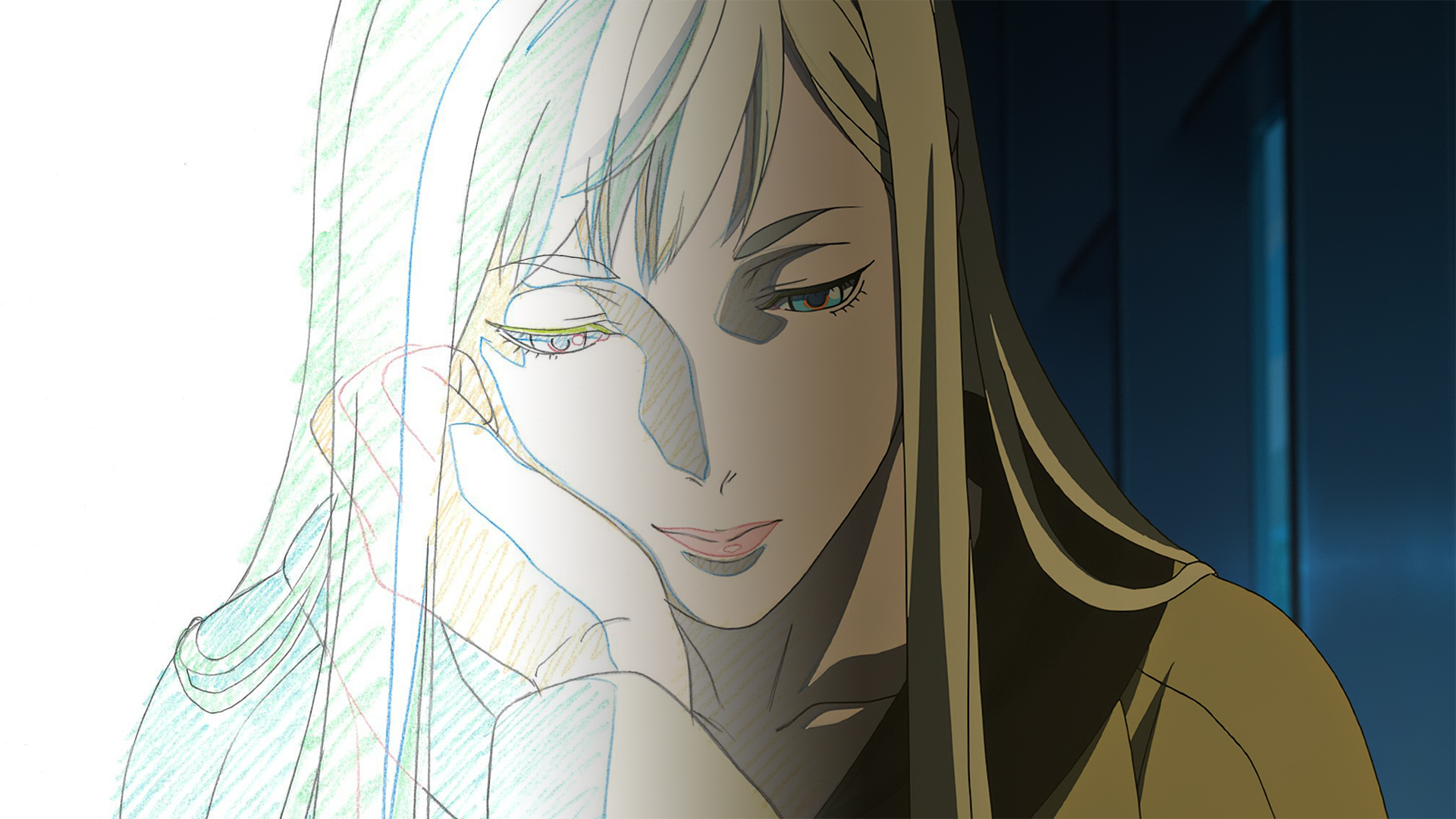

As important as the director’s role is, though, boiling it all down to Murase is doing a disservice to the team and their work, even more so given that Hathaway is the product of many creators who approach the idea of realism from their own angle. Look no further than the character design credit, which frankly does a poor job at highlight the important, specific work that these people did. For starters we have Pablo Uchida, who reimagined the whole cast trying to find the sweet spot between animation and reality, between established Gundam ideas and the freshness they wanted out of him. And not only did he draw the early drafts for all of them, but he also painted many pieces of concept art that were used as a color script of sorts for pivotal scenes in the movie; quite important, given that Murase will happily deliver a wholly dark and muddy experience if you don’t nudge him in another direction.

Following him you’ll find Naoyuki Onda and Shigeki Kuhara, who geared Uchida’s ideas to work in the context of animation. The two of them split the workload, with Onda taking the lead role by designing the main cast and acting as chief character animation director—everyone’s quick to credit him for the tremendous visual charisma Gigi Andalucia has throughout the film—and Kuhara focusing more on the side cast.

Unsurprisingly, it’s Onda’s flavor that’s more prevalent, which makes for quite the interesting mix. His career took off precisely under Tomino, arguably by barely surviving a tough dual role as key animator and in-between/checker in Dunbine and L-Gaim. Much like Murase, he’s been involved with Gundam more than a few times. One of those happened to be the Zeta Gundam: A New Translation films, which were produced during the early to mid 00s stretch of collaborations between the two that eventually led to Ergo Proxy—directed by Murase, with character designs and recurring supervision by Onda. Over time, the latter also developed his own approach to realistic animation. Onda is more focused on the supervision side of things since he strongly prefers that to key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. and other tasks, and achieves his threedimensional flair by carefully arranging facial features that look misleadingly simple; if you want an easy to comprehend example as to why that approach is not so easy, look no further than the melting disaster that was Inuyashiki.

So, what happens when you put together these two old comrades who feel strong mutual respect, to the point that Onda refused to correct Murase’s idiosyncratic animation for this very project? That loaded question already contains the answer. Murase was happy to allow Hathaway’s animation to be very much up Onda’s alley on the surface, but upon closer inspection, it often embraces Murase’s much more complex shading, even going multi-tone in dramatic spots. All of this, applied to characters with that fresh life-like touch that Uchida provided, and environments that can be realistic to an uncanny degree. So, while Murase had by all means the leading voice as the director, there are many tones to Hathaway’s realism.

While it’s a palpable Murase-like film, the fact that the scenes he personally key animated stand out like a sore thumb is very telling about his own style not being all there is to Hathaway.

One of the most interesting aspects of this realistic presentation is the double-edged sword that is Hathaway’s emphasis on the theatrical experience, especially now that you can’t take such a thing for granted. In his commitment to his vision, Murase didn’t hesitate to keep action sequences dark—and I mean, actually dark—when set at night. Mafty’s terrorist attack is brilliant in how it puts you in the shoes of civilians scrambling away without much of a clear vision of the events, making for a memorable, deliberately disconcerting moment. Only the flashes in the compositing process led by Kentaro Waki illuminate the scene—they’re majestic, otherworldly instants, but also a clearer look at how terrifying mobile suits rampaging around a city are. Murase called it a direct emulation of the novel; there’s only text in the original, you can’t truly see the robots, hence why the focus on how everyone is being affected by this grand action.

The downsides to that aren’t an issue in a theater setting calibrated to the Dolby Cinema standards they tuned Hathaway for, but on lesser screens, you might genuinely struggle to discern even the characters it focuses on. One of the ways to address that darkness that even Murase thought might have gone overboard was the audio, which was calibrated so that theaters equipped with Dolby Atmos tech would give the audience excellent positional awareness during the hectic moments… which also won’t help those watching at home with standard speakers, though they will at least enjoy the excellent sound direction. All things considered, I find the team’s focused commitment admirable, even with the loss of readability that you might have depending on your setup.

Does that mean there’s no genuine flaw to this life-like approach they went for, then? I wouldn’t say so, since some aspects to it feel like pretty unquestionable misses. Though I wouldn’t condemn the movie’s liberal usage of 3D layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists. and real locations, because the way they give it a real sense of place and atmosphere feels perfectly in line with the overall style, that’s where Hathaway shows its roughest corners. The characters don’t always feel like they inhabit that sorta-realistic sorta-artificial space, the locations based on real places sometimes drag you out of the experience rather than immersing you in it, and the approach makes rare shots where the perspective isn’t quite right stand out even more. Overall, Hathaway is undoubtedly a fantastic production with a very clear vision, but there are still aspects that I’d like to see polished up in the next two films.

The cherry on top of this notable production is one aspect that had been talked up quite a bit before its release: the character animation. As you’d expect from a Murase and Oda tag team, it’s got the constant articulation of the former with the sturdiness of the latter, for the most part staying within the realistic boundaries of their vision; Hiroyuki Terao might not have gotten that memo, especially when it comes to this sequence, but Gigi’s not one to play by the rules so even that felt weirdly fitting.

Otherwise, the movie’s an excellent showcase of down to earth acting by proficient character animators adjacent to Sunrise like Shingo Tamagawa and Hirotoshi Takaya, as well as very notable guests like Hiroyuki Okiura, whose ending to the climactic action sequence stands out even in this overall context of excellent realistic animation. Coupled with the aforementioned 3D layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists. and fairly involved camerawork that exploits the fact that the team used CGi previs at the storyboarding stage to come up with its setpieces, you’ve got an animated film that’s always interesting to look at. In the same way that the recurring discourse about specific fan favorite mecha titles being about the characters unlike the rest of the genre is nonsense, we can’t say that Hathaway is unlike the rest of Gundam by having great character animation—that has happened before, and will continue to happen as long as multitalented artists like Sejoon Kim, the aforementioned Takaya, or even Murase himself are given big roles. That said, Hathaway’s concentration of talent in this regard and the production’s thoroughly focused effort to achieve animation that feels realistic is by all means extraordinary, and for that it deserves the praise it’s getting.

Now, you might have realized that there’s a pretty important aspect to a mecha movie that I’ve avoided so far, since it happens to be related to a larger point I wanted to touch on. Which is to say, what about the goddamn robots?! While the effects stayed mostly traditional, and handled with expertise by experienced folks like Futoshi Oonami and Kenichi Takase, the mechs themselves were nearly entirely rendered using 3DCGi.

Before people run away in panic, it’s not particularly poor CGi—and even if it were, this movie would make it hard to notice that with its dark action settings. And yet, that decision alone makes it feel like a step down when compared to the output by this same Sunrise substudio. Mind you, this isn’t something that only the older audience used to 2D mecha animation thinks, but also a sentiment shared by the team. It’s easy to appreciate that in the rare, viscerally impressive shots of traditionally animated robots in the film. And, even more explicitly, the fact that Murase himself said he much prefers 2D over 3D robots—which he phrased with the caution of a director who shouldn’t blast the choices made in a movie of his that is currently being screened.

Why go with a solution that the director finds lesser, then? Murase explained that the Xi and Penelope Gundam are simply too complex of a design to move them freely otherwise. There’s obvious truth to that, as those are ridiculously intricate mechs, but that’s clearly not all there is to it; this team has plenty of mechanical designers who could have abbreviated the designs to smooth out the process without damaging the designs’ visual charisma, and let’s not forget that this is the same Sunrise branch that not that long ago was animating nightmarish levels of detail—sometimes by Murase’s own hand!

In that same interview, Murase also alluded to broader struggles in the industry when it comes to animating 2D mecha, as well as mindfulness of the team making him settle on the 3D route for Hathaway. That is much closer to the actual point, but just vague enough that I felt like it deserves clarification. Sure, we all know that traditionally animated robots are slowly on their way out, but isn’t Sunrise Studio 1 supposed to be an exception? Over the last decade, they’ve been a bastion of high quality 2D mecha, having produced the likes of Gundam Unicorn, Thunderbolt, and even the very traditional feeling G-Reco. Titles of theirs that overlapped with Hathaway’s production like Gundam NT were still very much reliant on 2D mechanical animation, so it’s not as if it became a lost art while they were preparing this project. That overlap is actually part of the issue, but it’s not as if Studio 1 was simply too busy at the time; sure, they’re currently making Yashahime for the simple reason that they were the ones to produce Inuyasha back in the day, but to say that they haven’t dedicated it many resources would be to put it quite kindly.

When it comes down to it, it’s not as if Hathaway—nor the industry as a whole, still—lacks 2D mechanical aces as people understand them. Most of the big names from the likes of Unicorn are still around and with big roles at that; this includes multiple people we’ve already gone through, plus the likes of Nobuhiko Genma, Seiichi Nakatani, Iwao Teraoka, and so on, all of whom showed up big for Hathaway. The anime industry is still filled with dozens upon dozens of specialists capable of handling mechanical animation directionAnimation Direction (作画監督, sakuga kantoku): The artists supervising the quality and consistency of the animation itself. They might correct cuts that deviate from the designs too much if they see it fit, but their job is mostly to ensure the motion is up to par while not looking too rough. Plenty of specialized Animation Direction roles exist – mecha, effects, creatures, all focused in one particular recurring element. and key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. for demanding 2D mecha shots—and that’s without factoring in the multitalented ace animators whom people don’t usually count among this crowd. The problem is not individuals, it’s teams, and often the parts of them that go overlooked.

With this industry’s shift towards 3D animation for mechanical work, the first thing that is being lost is the training of new mecha animators. Gundam producer Ogata is someone you always have to take with a grain of salt, as his job is literally selling you on the franchise and Sunrise themselves, meaning that he’ll swing from talking up the studio’s ability to produce traditional mecha to saying that 3D is an unavoidable pitfall that actually has its upsides when convenient. That said, he hit the nail when he mentioned the shortage of in-betweeners trained in this specific field. In spite of this industry’s disregard for the role, in-betweeners play a key role in the perceived quality of the animation, and even more so with mechanical animation where maintaining the solidity of objects is often a crucial aspect; it’s not a coincidence that certain 2D mecha aces used to have cherrypicked in-betweeners, including people whose regular work was key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style., to ensure that their shots were properly realized.

This isn’t to reduce Hathaway’s problem to just a lack of prepared in-betweeners, but rather to highlight the industry’s growing inability to put together teams with people ready to handle 2D mecha’s specific demands on every stage of the production, especially if you’re subjecting it to the high standards a project like this deserves. It’s always possible to bruteforce a fully 2D mecha title with a crew that isn’t necessarily used to that… but charming as it was, Granbelm is a clear example that something’s going to feel noticeably off if you do that. The future of 2D mecha will be in being smart with the workload split with 3D teams, or being exceptionally lucky with your timing and managing to gather one of those increasingly rarer teams.

What about right now, though? There are still some places in the industry where you need less of a miracle for the latter option to happen. Studios such as BONES, with a solid tradition in mecha anime, have a bit of an easier time gathering a team of experts like the ones currently wrapping up the production of Eureka Hi-Evolution—Tomoki Kyoda’s fever dream, which might very well be one of the last showcases of 2D mecha on that insane scale. And of course, Sunrise is one such place as well. Studio 1 will likely switch to 2D animation again when there’s less on their plate, and then there’s the case of SUNRISE BEYOND, which might have been a factor in nudging Hathaway towards 3D as well.

Long story short, Sunrise Studio 3 was the crew that handled all the daytime, non-spinoff Gundam series since SEED Destiny. Given the format they worked with, the scope of their work wasn’t as ambitious as Studio 1’s usually is, but their commitment to 2D mecha was real and they did a more than respectable job with it—especially once the team was reenergized during Build Fighters. Following Sunrise’s constant reshuffling, though, they got rolled into SUNRISE BEYOND after the studio acquired Xebec, which happened to be another crew with a bit of a mecha tradition. While they’ve already produced a couple of titles under that name, their first big role will be in launching a new mecha IP later this year with Kyoukai Senki. Given this scarcity of mecha resources and big projects brewing fairly close, I’m sure you’ll understand why Hathaway took the 3D path—even if you, like its director, happen to think it’s kind of a shame. Otherwise, I have to reiterate: what a cool movie!

Staff

Director: Shukou Murase

StoryboardStoryboard (絵コンテ, ekonte): The blueprints of animation. A series of usually simple drawings serving as anime's visual script, drawn on special sheets with fields for the animation cut number, notes for the staff and the matching lines of dialogue.: Shukou Murase, Shinichirou Watanabe

Unit Direction: Kou Matsuo, Hidekazu Hara, Mitsuhiro Yoneda

Character Designer: Pablo Uchida, Naoyuki Onda, Shigeki Kuhara

Mechanical Designer: Hajime Katoki, Kimitoshi Yamane, Seiichi Nakatani, Nobuhiko Genma

Chief Character Animation Director: Naoyuki Onda

Chief Mechanical Animation Director: Seiichi Nakatani

Effects Animation Director: Shuichi Kaneko

Mechanical Supervisor: Nobuhiko Genma

Character Animation DirectionAnimation Direction (作画監督, sakuga kantoku): The artists supervising the quality and consistency of the animation itself. They might correct cuts that deviate from the designs too much if they see it fit, but their job is mostly to ensure the motion is up to par while not looking too rough. Plenty of specialized Animation Direction roles exist – mecha, effects, creatures, all focused in one particular recurring element.: Iwao Teraoka, Takahiro Kimura, Shigeki Kuhara, Marie Tagashira, Takehiro Hamatsu, Shoto Shimizu, Jun Shibata, Sejoon Kim, Rin Riku, Takayoshi Watabe, Hirotoshi Takaya, Shingo Tamagawa, Shinjiro Mogi, Kayano Tomizawa, Toshimitsu Kobayashi, Atsutoshi Hashimoto, Hiroya Iijima, Shuji Sakamoto

Assistant Character Animation Director: Tomoko Sugidomari

Assistant Animation Director: Morifumi Naka, Toshihiro Nakashima, Yasuhiro Moriki, Shuhei Arita

PhotographyPhotography (撮影, Satsuei): The marriage of elements produced by different departments into a finished picture, involving filtering to make it more harmonious. A name inherited from the past, when cameras were actually used during this process. Director: Kentaro Waki

Key AnimationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style.: Shuji Sakamoto, Nobutake Itou, Hirotoshi Takaya, Hisako Sato, Takashi Tomioka, Takayoshi Watabe, Rin Riku, Takuya Saito, Yoshihito Hishinuma, Takayuki Gotan, Hiroyuki Terao, Eiji Komatsu, Miyuki Katayama, Jiko Abe, Kaichirou Terada, Takehiro Hamatsu, Tetsuya Ishii, Kazuhiro Itakura, Keiichi Sasajima, Masahiro Koyama, Futoshi Oonami, Satoshi Nishimura, Shingo Tamagawa, Satoshi Nagura, Toshihiro Nakashima, Kazuhiko Shibuya, Masaki Hinata, Hiroya Iijima, Kento Toya, Tomoyasu Kudou, Shouta Ihata, Shinjiro Mogi, Marie Tagashira, Hiroyuki Okiura, Yoshihiro Watanabe, Seiichi Nakatani, Shukou Murase, Shunji Murayama, Kenichi Takase, Yu Ikeda, Takashi Habe, Yuichi Tanaka, Tomohito Hirose, Manabu Katayama, Makoto Yamada, Tsukasa Dokite, Sanae Shimotani, Katsutoshi Tsunoda, Shinichi Takahashi, Hiroyuki Mori, Ryouji Shiromae, Kouhei Tokuoka, Shingo Takeba, Kensuke Watanabe, Daisuke Shibukawa, Shuhei Arita, Kayoko Ishikawa, Mitsuhiro Yoneda, Shigeki Kuhara, Kumi Ishii

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

I had a feeling that mecha anime was held back due to diminishing numbers of mechanical animators and lack of new ones being trained, but it never occurred to me that a lack of mechanical in-betweeners would also hamper mecha anime production. It’s one of those things that you don’t think about, but makes everything click into place when you do. Also the funniest part about the new Sunrise IP was once the trailer finished, they already trying to sell model kits for the show.

It makes sense. The industry puts inbetweeners down, praise always goes to the Key Animator, people critiquing these Animated films always puts down inbetweeners as newbies. As an Animator myself also 2D Animating more simple mecha in my own Animated show, understands the importance of inbetweeners. They are just as important to Animation as a Key Animator. If that is why Mecha Anime are not doing 2D Animated Mecha, then unfortunately, it is a karma we all have to deal with. I know there may be a future production that can do it but also respecting their Animators as well.

So bad that the mechas themselves where not in 2D animation

One of the most important takeaways I’ve gotten from this blog is that douga artists are important as hell, and they deserve SO much better than what the industry (with the probable exception of KyoAni) is giving them.

*60 key animators*

damn

High-profile Sunrise productions are a bit of an exception to the rule in that they pile up animation staff like nothing else, not out of necessity but by design – very apparent on the animation direction front. There are downsides to the approach but it does allow a lot of very allowed people to contribute, and the level of polish they achieve is undeniable.

what’s the downside other than the timeframe? the quality is top-notch

Not efficient in any way, you can lose the holistic excellence that can result from an animator conceptualizing a whole scene by splitting things too much (there’s a good reason this movie still went out to preserve that in key sequences!), and overabundance of ADs can erode individual character on top of being an absolute nightmare to manage. In this case specifically, I’d absolutely agree with you, the movie does look fantastic so no big deal.

The fate of 2D mecha will be in being keen with the responsibility split with 3D groups, or being incredibly fortunate with your planning and figuring out how to accumulate one of those inexorably more extraordinary groups.

Man you guys should’ve covered origin too it was a solid ova series

Hmm the 3D mecha scene started at sunrise with zegapain (2006) which was a visually quite in unimpressive show. It’s concept and execution of it is quite awesome tho theme exploration is also decent i really wished they used 2d mechs.CGI really butchered the action scenes in it maybe it was fault of the director masami shimoda too well who knows