Shirobako’s Secrets: The Most Deliberate Anime Industry References

To celebrate the recently announced Shirobako movie, which will finally give us a chance to follow Aoi Miyamori’s adventures further into the path of anime production, we returned to the TV series to compile some of the most amusing and enlightening nods to real creators and anime industry events that you may have missed throughout the show. Hop on for a fun educational time!

Don’t get me wrong: that Shirobako is an excellent series does by no means come down to the fact that it’s chockfull of industry references. It’s first and foremost a very relatable tale for young creators no matter their field, as well as a very respectful portrayal of anime’s making process that manages to be fairly instructive while exaggerating enough details to be a ton of fun. Had it been a bit more inspired with its execution, exploiting the fact that it’s an anime about anime, I would easily consider it an all-time great as opposed to the simply extraordinary series I believe it ended up being. That said, there’s no denying it all was enhanced by the fact that series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario. Tsutomu Mizushima is an anime veteran who deeply cares about this medium, with an incredible list of contacts and a firm grasp of this industry’s history. Shirobako’s endless cameos aren’t just random appearances of popular titles, amusing as those can be. For the most part, the series employs very deliberate nods to creators and events that feel unobtrusive to unsuspecting viewers but add extra layers of enjoyment for the viewers that catch them. Mizushima & co offered the possibility of a richer experience while ensuring the show was entertaining on its own right.

Back when the show first aired I made an effort to highlight many of those nods (with pictures that got borrowed by the JP fandom then spread like wildfire, amusingly enough), and now is the right time to put all those notes into proper form, explaining not just the references but the smart intent behind them. Enjoy this rundown of the most interesting instances!

─ Right off the bat Shirobako is loaded with references to existing companies and real titles, but the most important point is just how many staff members from fictional studio Musani Animation are loving caricatures of actual artists. Some only become obvious with time and are relatively minor – though seeing Miyamori’s voice actress check up on assistant color designerColor Designer (色彩設定/色彩設計, Shikisai Settei/Shikisai Sekkei): The person establishing the show's overall palette. Episodes have their own color coordinator (色指定, Iroshitei) in charge of supervising and supplying painters with the model sheets that particular outing requires, which they might even make themselves if they're tones that weren't already defined by the color designer. Naomi Nakano like their characters within the show is no small pleasure – while others play key roles in the series; director Seiichi Kinoshita is based on none other than Seiji Mizushima, a role he was so proud of he went on to mimic the character himself, while company president Masahito Marukawa is an obvious nod to living legend Masao Maruyama, an equally affable studio leader who may or may not also share cooking skills with him. And of course, knowing that the behavior of Musani’s number one dork Tarou Takanashi is based on Shirobako’s own director, who handled similar tasks when he joined the industry, makes their ordeals even more amusing.

─ The next major batch of references is audio related. Exodus’ voice actresses are painfully obvious nods to Mai Nakahara, Shizuka Itou, and Ai Kayano, to the point of recreating actual outfits of theirs. Veteran sound director Yoshikazu Iwanami also makes an appearance, as does Shirobako’s own sound production manager Rie Tanaka and sounds effect technician Yasumasa Koyama. And since it couldn’t be any other way, all the action occurs within Studio T&T’s actual workplace. This is the level of thoroughness they kept during the whole show.

─ But when it comes to the production of Exodus, the most interesting details relate to the links between the struggles within and outside the show, and how the solutions they arrive to also mirror what the real creators did. It’s been confirmed that the FTP issues they suffer in the third episode were directly based off something that did happen to them for example, and things only get more fun from that point onwards. Yumi Iguchi, mostly modeled after real animator Yuki Imoto, holds a similar position as Yuriko Ishii does with P.A. Works, as one of the animation aces of their studio. So when the director requests an emergency retake for a critical sequence, it only makes sense that she was the one to animate it in real life like Iguchi did at Musani.

─ Similarly, their issues with Exodus #8 found a solution in the real world. After the staff’s heavy arguments regarding the balance between hand-drawn and CG animation, it’s an avatar of Ichiro Itano of iconic missile circus fame who begins speaking sense to them – no better candidate, since he’s personally transitioned from 2D to 3D because he no longer was capable of drawing steady lines. After bonding through a faux Ideon (which Itano was a key figure in) exhibit, their traditional and CG animators reach an agreement to split the workload by having hand drawn explosions and 3D vehicles for the scene that caused this whole mess. The sequence drawn by Musani’s effects expert was brought to life by real 2DFX master Nobuhiko Genma. While Shirobako’s animation is very modest, both Mizushima and P.A. Works president Kenji Horikawa did their best to exploit their extensive lists of acquaintances to give extra significance to special moments like this.

─ On a very different note, just so that you see how Shirobako managed to grow even more meta after ending, the award that director Kinoshita remembers himself winning is a parody of the Animation Kobe… which both Mizushima and Shirobako itself went on to win, at the very last event they held. Layers upon layers.

─ The next point of interest is Ema Yasuhara’s character arc. As an animator in a series about making anime that mirrors the real world, her idols are very easy to identify. While hanging out with her friends, she admits that her dream is to be able to portray life like Horiuchi from Naniwa Animation – a clear reference to Yukiko Horiguchi, who during her years at Kyoto Animation became a modern icon of character acting in the world of Japan’s TV animation. When Ema struggles to draw a cat, she’s mentored by Musani’s veteran Shigeru Sugie, an anachronic nod to Toei Douga legend Yasuji Mori; beyond being a central figure in the golden age of the studio, the mentor of plenty of superstars, and the very first person to hold the title of animation director in anime, Mori also happened to be an expert drawing animals, so of course he’d be the first one to coach Ema on this problem.

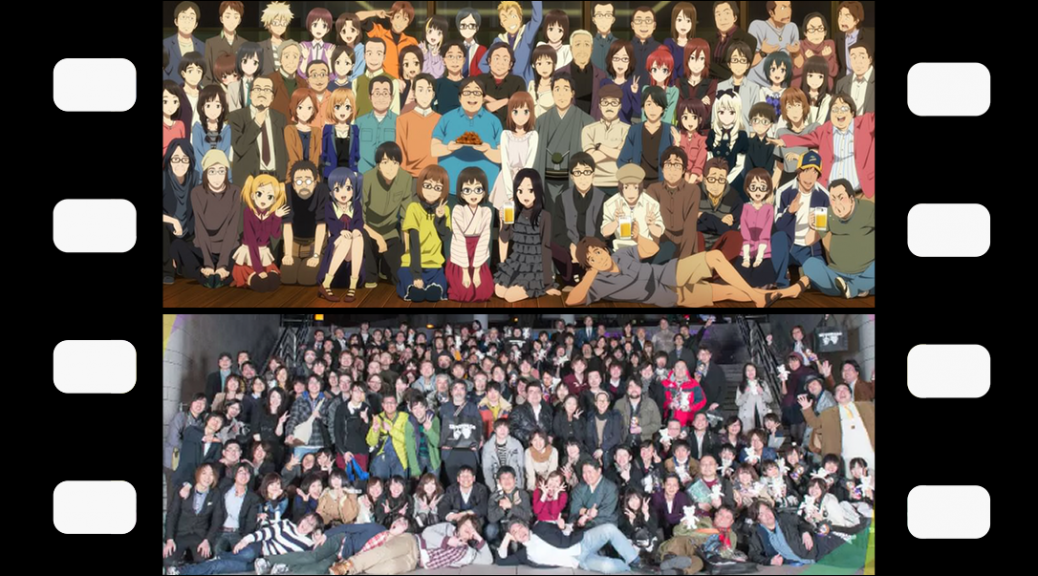

─ The last stretch of Exodus’ production is again full of nods to real people; look no further than emergency writer Shimeji Maitake, whose name was inspired by Type-Moon’s Kinoko Nasu but actually represents scriptwriter Hiroyuki Yoshino, or currently MAPPA-affiliated animator and intricate designer Naoyuki Onda with his badass persona. There’s also a fun detour involving a bat-wielding version of studio BONES’ president Masahiko Minami and his good pal Yuuji Matsukura, producer at JC Staff. If you ever worry that those caricatures might have been poorly received, keep in mind that Minami showed up at the party to celebrate the production’s end dressed up as his character, and that Matsukura actually produced director Mizushima’s next series Prison School. It’s all in good faith!

─ When it comes to noteworthy cameos however, it’s hard to top the one and only Hideaki Anno, who should be glad of how much younger Shirobako makes him look. Beyond the killer Evangelion-themed couches and his sensible answer to Miyamori’s worries, what stands out the most from his appearance is the recreation of his iconic scene in Nausicaä, which allowed him to win over Hayao Miyazaki. Following anime Anno’s recommendation, Miyamori returns to Musani’s old ace Sugie, to exploit his expertise drawing animals – yet another chance to honor the figure of Yasuji Mori that inspired the character. But since asking a dead person to animate would be unreasonable even for an exceptional project like Shirobako, they instead got sakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. star Toshiyuki Inoue to animate the sequence no one else could handle; as the most capable veteran that P.A. Works has access too, Inoue fits that important role nicely! Exodus‘ production finally wrapped up, and with the inclusion of an episode as one of Shirobako‘s Blu-ray extras, we were able to see the names of all characters who we’d seen doing their best in its fake credits roll. At this point, Musani Animation might as well be real.

─ With the arrival of the second half of the series we’ve got a new production in the form of Third Aerial Girls Squad, new characters, and of course a metric ton of references to real people and companies. The original author of the series Musani gets entrusted with was modeled after Takeshi Nogami, who embraced this role and drew a couple of chapters of the manga by his anime self. President of Enterbrain and various Kadokawa branches Hirokazu Hamamura inspired one of the main executives behind the project, while producer Gotaro Katsuragi is a persona of Yuta Todoroki – look at him happily recreating his cut in the second opening! Even president of Production I.G Mitsuhisa Ishikawa makes a cameo appearance during this arc, handling more modest work than you should expect from him nowadays since Shirobako chose to mirror his humble beginnings instead.

─ Among the countless cameos, a couple of appearances stand out as particularly interesting. One of them is high-profile art directorArt Director (美術監督, bijutsu kantoku): The person in charge of the background art for the series. They draw many artboards that once approved by the series director serve as reference for the backgrounds throughout the series. Coordination within the art department is a must – setting and color designers must work together to craft a coherent world. Hiromasa Ogura, one of the few people in his field who has earned enough recognition to have his work analyzed by scholars without being a side note on a popular director’s work. Having worked with him in the past, Mizushima even gets away with portraying him as a moody, weird genius, in a way that feels very endearing. In the end, Musani’s unreasonable demands were fulfilled by Ogura himself, since the real one painted the special background they needed in the show. Similarly, when the studio is in such a pinch they need to rely on an experienced director who’s become a bit of a crazy hermit, Mizushima chose to model the character on his veteran acquaintance Takashi Ikehata, who’s gladly kept on collaborating with him even after being showcased as a weirdo who really doesn’t want to work. Had Shirobako not been directed by someone in good terms with this many creators, this would have been impossible.

─ Though I’ve kept stressing that all of Shirobako‘s caricatures are in good faith, that doesn’t mean that it pulls any punches. The company behind Third Aerial Girls Squad clearly represents real publishing behemoth Kadokawa, which makes the figure of their insufferable editor rather interesting. Somewhere out there, an editor who pushed unreasonable demands on Mizushima and refused to relay information properly has been keeping quiet, so that people don’t realize that one of the most popular original anime in recent times was openly dunking on them. Funny story, that. The show’s amusing but acid portrayal of a messy outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio. studio, the identity of which got hidden by Mizushima modeling it after an unrelated building in Girls und Panzer‘s setting (which they loved), also seems to have spawned from an old grudge. It’s true that Shirobako wears rose-tinted glasses, as a series meant to inspire young creators should, but its occasional criticism is quite sharp.

─ Despite all those adversities rooted in real problems that the cast had to face, Shirobako is a tale about triumph in the end. The miscommunication issue, partly based on the controversy that surrounded Shirokuma Cafe, is finally solved and thus the production of Third Aerial Girls gets heroically wrapped up at the very last second – which technically qualifies as a reference to most anime made nowadays, including Shirobako itself. There’s no end to the minor nods to other artists, events, and titles present in this series, but by detailing the most significant ones I hope we’ve given you greater appreciation of how special of a project Shirobako was. A delight for those who walked in blind, and even more of a treat if you’re aware of just how deliberate its portrayal of the anime industry is. If you haven’t seen it yet, the announcement of the sequel film is a perfect chance to do it!

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

>”company president Masahito Marukawa is an obvious nod to living legend Masao Maruyama, an equally affable studio leader who may or may not also share cooking skills with him.” The absolutely worst thing about Lockerz.com going down was losing access to many photos that Mr. Maruyama posted on his account there, of all his so-called “MAPPA meals” (MAPPA飯). Some photos are still available on other of his social networks’ accounts though (https://twitter.com/MasaoMaruyama/status/203751054553268224). The part about those looking brown is definitely real! 😀 I hope he keeps cooking for peers at Studio M2, or anywhere else he ends-up in, for years… Read more »

Maybe that’s the true value of M2: by moving to a small studio with barely anyone around, they all get to eat Maruyama’s food.

even though a lot of these references will fly over an average viewer’s head, Shirobako has such great writing, characters and valuable surface-level insights on so many topics that i think every anime viewer should experience it.

I enjoyed the article has nice insights and hey the JP fandom has noticed your work and will keep borrowing it ^-^ that is just the way it is. I can’t wait for the movie and more Rocky Chuck!..

Thanks for the great background info! It’s amazing how much has been packed into the anime. One question pops into my head any time these details are listed: How did they find the time to write and animate the series? When even standard anime are portrayed as being very hard to finish in time, I just have to wonder who put in the time to do this!

To be fair it’s not like Shirobako is that ambitious of a production, it just has a lot of thought put into it in this regard. Otherwise it’s a pretty tame 2 cours anime – which by itself is a ton of work, of course.

the average is 25 weeks for one episode.

2 month for the e-conte, 1 month for the layout, 1 month for genga, 2 weeks for douga, 2 week color and photography, 1 week for the dubbing+sound effect+douga check, 2 weeks for the editing.

“Studio Titanic” wasn’t supposed to be Shaft, was it?