Ghibli Star Kosaka Kitaro Confronts The State Of The Theatrical Anime Industry: Okko’s Inn [Annecy 2018]

The massive success of anime movies in recent times is causing a quick, big expansion in this field. We’re now getting all sorts of movies by high-profile anime creators, to the point that the comeback of studio Ghibli-affiliated Kosaka Kitaro to direct a movie 11 years after Nasu: A Migratory Bird with Suitcase doesn’t seem all that extraordinary anymore. Unfortunately, it’s not all good news – Okko’s Inn is a fascinating little film that showcases many of the problems that creators in this sector of the industry have to face nowadays, from worries about cross-media marketability to a shortage of properly trained staff. While it didn’t succeed in all of its aspirations, the story of this movie and how it came to be is well worth paying attention to.

It’s out of sincere appreciation that I say that the theatrical adaptation of Wakaokami wa Shougakusei!, localized as Okko’s Inn for the international English-speaking audiences, most likely shouldn’t exist. As a series of novels for children it enjoyed its fair share of popularity, but that tale has been over for as many years as this adaptation has been in the making. Keeping in mind the difficulty of monetizing a title like this in any meaningful way, as producer Masahiro Saito acknowledged, the mere existence of this movie is bewildering. When you also consider the Ghibli-affiliated legend leading the project, the difficulties the production team had to face, and the fact that it was also accompanied by a TV anime, Okko’s Inn feels like enough of a miracle that I don’t mind looking past the shortcomings of this sweet, unlikely film.

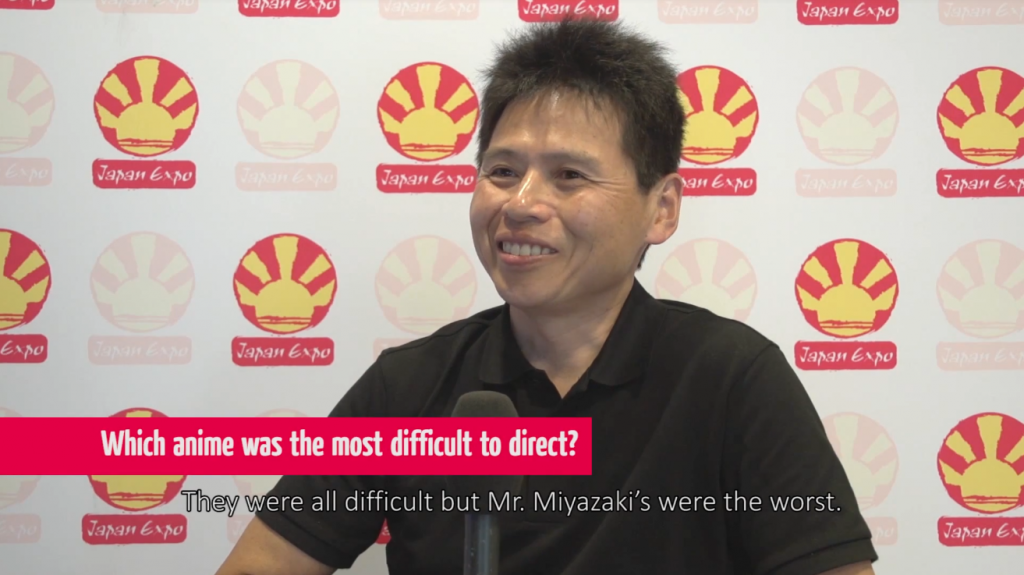

To understand where it comes from in the first place I feel like it’s necessary to introduce director Kitaro Kosaka. It’s not as if he’s an unknown figure, having been a visible Ghibli star for decades, but there’s a tendency to uncritically parrot the statement that he’s Hayao Miyazaki’s right-hand man rather than explaining what that entails and how people came to believe that. And don’t get me wrong: it’s a fair assessment, since their careers are very deeply connected. So much so that Kosaka got into this industry in the first place because of Miyazaki’s pre-Ghibli works, then tried (and failed) to join studio Telecom where his idol was temporarily stationed. Kosaka strategically decided to join Oh! Production, the energetic animation muscle supporting some of anime’s best work at the time, since he knew Miyazaki relied on them. His wager and all the effort he put into his work paid off as he was invited into the production of Nausicaä, starting a long series of collaborations.

Now don’t take that to mean that it all went smoothly. It rarely ever does when Miyazaki is involved. In fact, that very first Ghibli project was quite the harsh experience for Kosaka; his reckless, sometimes unprofessional approach to the work at the studio led to Miyazaki kicking him out, hence why he focused on Isao Takahata movies for a while… leading him to realize that the other main figure at the studio was, if anything, more demanding than Miyazaki. But his perseverance paid off, since he was allowed to become an animation director on the likes of Princess Mononoke and Spirited Away. Over time he became the most regular supervisor on Miyazaki’s movies, while still assisting other directors at the studio. It’s quite telling that he was allowed to oversee the animation of The Wind Rises all by himself – after that many years, very few people if any at all were as adept as Kosaka at ensuring the idealized animation in Miyazaki’s brain could more or less be given form in the real world. It wasn’t easy, though!

That should be enough to get across the crucial role he played at the studio, but exactly how did he earn that much trust? Versatility and stability were two qualities that helped him stand out among his peers, even before he became a fully-fledged director. His ability to retain the appeal of the source material when adapting it to animation was put to good use with studio Madhouse – he was able to maintain CLAMP’s aesthetic in the Clover music video he handled, and most impressively, he won over none other than Naoki Urasawa. As you might have heard, the mangaka is notoriously protective and advocates for very strictly faithful reinterpretations of his own material. However, Kosaka won him over so much after Yawara and especially Master Keaton that he insisted to have him return to draw MONSTER’s concept designs, even though Kosaka wouldn’t be available for the actual production.

And once he was given an opportunity to lead projects of his own – once again because of Miyazaki’s intervention, as he recommended Nasu to him but refused to adapt it at Ghibli – that ability to preserve the essence of an original work took on a more conceptual spin. Kosaka would make research trips to ensure the particular folklore and customs of the setting were respected, put equal amounts of effort into the subject matter, and portray the unique mundanity of each story via tricks like very elaborate eating sequences. 15 years after Nasu: Summer in Andalusia we’re getting Okko’s Inn, a new movie that follows those exact same precepts. It’s not as if Kosaka’s mindset hasn’t evolved throughout the years (he once proclaimed to have no interest in fantastical stories as opposed to his master, yet here we have him directing a cute ghost film), but the core of his ethos remains the same. Though his directorial work is quite sparse, Kosaka is a creator who has a very clear idea of what he wants to convey.

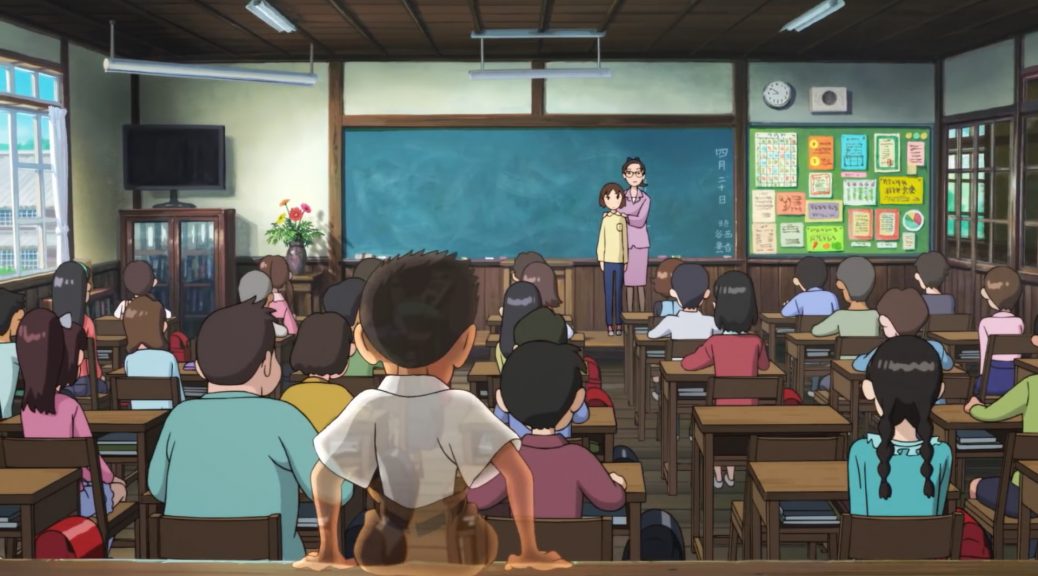

How did that solid vision fare this time around, then? All things considered, quite well…though I do mean that the circumstances should be kept in mind, since Kosaka and his team had to face a series of problems sparking within and outside the story. This tale follows the titular elementary school girl as she moves with her grandmother to a traditional Japanese ryokan. The adventures that follow after she meets the ghost of a boy and stumbles into becoming a young innkeeper go through similar series of events in both formats of the adaptation, but they have very distinct texture; whereas the TV take on Wakaokami wa Shougakusei! squarely aimed at children is a pleasant series, the theatrical Okko’s Inn drops the explicit reference to elementary schoolers from the title as it aims for a more general family audience. That allows it to keep its cute backbone, but also to have an unsettling thread dealing with the protagonist’s PTSD – subtle for the most part, but genuinely visceral and asphyxiating in a couple of instances. The way it gracefully combines the two registers is one of its greatest accomplishments. It already feels like the kind of movie you’d enjoy as a child, and then find a whole new level of appreciation for it if you revisited it years later.

Unfortunately, the movie’s writing isn’t all that elegant otherwise. I’m the first person to advocate for more anime movies that don’t follow standard narrative structures, but these episodic adventures feel glued together in a fairly crude way, making for a more awkward experience than straight up binge-watching episodes. Okko’s gradual improvement as an innkeeper is the element meant to keep it all together, but that again flows more naturally in the TV series. And that is the crux of the issue: Okko’s Inn deals with material that, as it is, inherently fits serialized delivery much better. Although the TV incarnation ultimately doesn’t leave as strong of an impression, it’s a more consistent, well-constructed narrative. I’m fond of both takes yet gravitate more towards the movie version, but your mileage may vary depending on what you value more in your media experience.

As I mentioned earlier, some of the problems Okko’s Inn had to face didn’t quite stem from the narrative itself, but rather from the production circumstances. It’s no secret that Kosaka has quite the high standards when it comes to animation; most of his career has been dedicated to studio Ghibli’s lavish productions, and his personal projects with other crews stand out for their very stable animation, maintaining polish despite his use of complex cuts and troublesome angles. The fascinating volumetric aspect of his works has reached its zenith with Okko’s Inn – in an ironic turn of fate, it’s the movie about ghosts that makes bodies feel as if they were tangible and occupied space better than pretty much any other anime. Though there’s a handful of weaker drawings in the second half of the movie, those only stand out because of the truly exceptional job the staff did otherwise. In spite of the director’s demanding approach, things turned out very well in the end.

But that’s where things take a final nasty spin. The team put together an exceptional production despite (and because of) Kosaka’s ambitious vision and something else. As he detailed in Annecy, the truth is that this movie had been in the making for about 4 years, and relied on a team of mostly female animators who didn’t have experience on theatrical projects and thus needed lots of guidance. The reason? Veteran male animators simply decided to pass on the project, because a kid’s series led by a girl didn’t resonate with them. Even leaving aside the very questionable implications there, projects like this force us to face the fact that anime’s shortage of capable staff is a very real problem. That’s something that applies to the industry as a whole, but even more so to the theatrical space; actual anime movies (as opposed to film spinoffs screened in theaters) are a different beast altogether, hence why there’s a group of creators who are exclusively dedicated to such projects. Calling them better artists would be oversimplifying the issue so much that the point gets lost – they tend to have stronger draftsmanship and technical knowledge, but it’s also a different set of priorities, with a more thorough understanding of acting at the forefront. Movie animation might as well be a different skillset.

So as interesting as the current boom in anime movies is, and no matter how many fantastic works we get out of it, we can’t ignore the danger of spreading movie artists too thin. Kosaka had the feeling that he was fighting for staff with Mamoru Hosoda’s Mirai, since that was another high-profile anime film that overlapped with his production. What he might not be aware of however is that Hosoda lost some of his important assets to Mari Okada’s Maquia, which had a spectacular lineup but likely also suffered from the scarcity of animators in some way or the other. If Your Name was an exciting showcase of what the post-Ghibli theatrical anime space had to offer, Okko’s Inn is an equally important warning sign of the dangers of expanding too fast. We’ll be in a better place if more young artists receive the training you need to become a proper movie-level creator, but forcing our way there doesn’t seem advisable. That this movie turned out so well despite this whole mess feels like another of its small miracles.

And at the end of the day, this is what sticks out to me. As cheerful and carefree as it looks on the surface, Okko’s Inn is a brave project. It had the courage to bet hard on an essentially unmarketable property, to shoot for the moon animation-wise even though it lacked the experienced staff it would need, even to attempt to depart from standard film narrative structures. The degree to which it succeeded at its deceptively ambitious goals varies, but I can only respect a cute movie that tried so hard.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

“Veteran male animators simply decided to pass on the project, because a kid’s series led by a girl didn’t resonate with them.” I’ll confess this surprises me a bit, considering how closely I associate Miyazaki’s brand at Ghibli with kids’ films starring girls, My Neighbor Totoro being perhaps the premiere example but also things such as Kiki’s Delivery Service and Spirited Away, not to mention the sort of anime Miyazaki and Takahata had been working on before starting Ghibli such as Anne of Green Gables and Heidi. That tradition of drawing on female-led children’s literature is something Yonebayashi has carried… Read more »

I think there’s a subtle but important difference between those family movies for kids to enjoy, and something squarely aimed at young children – which is what Wakaokami was Shougakusei was, at least before Kosaka got his hands on it. The dropping of the Elementary Schooler from the localized title (which Kosaka would have liked to apply to the JP title as well) is a good example of that vague yet meaningful difference. I still think it’s lame they refused, though. I wouldn’t blame any individual for their decision, but I think there’s a bit of a problem when this… Read more »

Just out of curiousity, mind listing movie-level animators?

Inoue, Honda, Okiura, Hamasu, Honma, Suetomi, the entire Ghibli troupe (not just employees but frequent collaborators) – there are a bunch of people with diverse styles but sort of a shared mentality and skill level that allows them to specialize in movies

I’ve taken up learning to identify and interpret written Japanese on a leisure. The sign over Okko’s grandmother’s inn reads 春の屋reads but I am unable to distinguish the last character(s) just above the artist’s red inkan. It would be reasonable to assert that 旅館 would be the characters or possibly りょかん since this is a children’s anime…however, I remain uncertain as stroke patterns do not match either form and would be thankful for a helpful response.