Noburo Ofuji: An Award To Carry On The Legacy Of An Anime Pioneer

Today we’ll look at the career of Noburo Ofuji, an anime pioneer who advanced Japanese animation for as long as he lived, and then had that spirit live on through Japan’s oldest and most prestigious animation award. Be it commercial animation or indie works, Ofuji’s vision has endured to keep on awarding anime’s most innovative works!

The winners for the 73rd edition of the Mainichi Film Awards were announced last week, before the ceremony that’s due in February 14. Awards are a topic that we rarely deal with in this site, since people are already too quick to treat them as the ultimate arbiter of worth. Seeing Mamoru Hosoda’s Mirai receive the Academy’s very first non-Ghibli Japanese nomination in the Best Animated Feature category filled me with joy as the film had been broadly misjudged due to its own misleading promotion, but neither that elevated the movie nor will the world end when it inevitably doesn’t win an Oscar. While acknowledgment is important in a climate where creators have to worry about sustainability, obsessing over this isn’t the healthiest relationship to have with media.

That’s not to say that there aren’t interesting awards worth digging into, though. Be it because of their exceptional curation or the history behind them, some awards go beyond being a pleasant footnote in an artist’s career to function as valuable collections of their own – especially when they have a very clear, unifying vision. And, when it comes to anime, one name towers above them all: the Noburo Ofuji Award.

But before we get into this unique award, what’s most important is detailing who Noburo Ofuji was and how he ended up with such a prestigious prize to his name. Truth to be told, if you’re at all interested in the roots of Japanese animation, then chances are that you’ve at least come across Ofuji’s name before. He’s rightfully considered one of anime’s progenitors after all, so he’s hardly an overseen figure in academic spheres. To bring everyone else up to date, though, let’s quickly summarize his career.

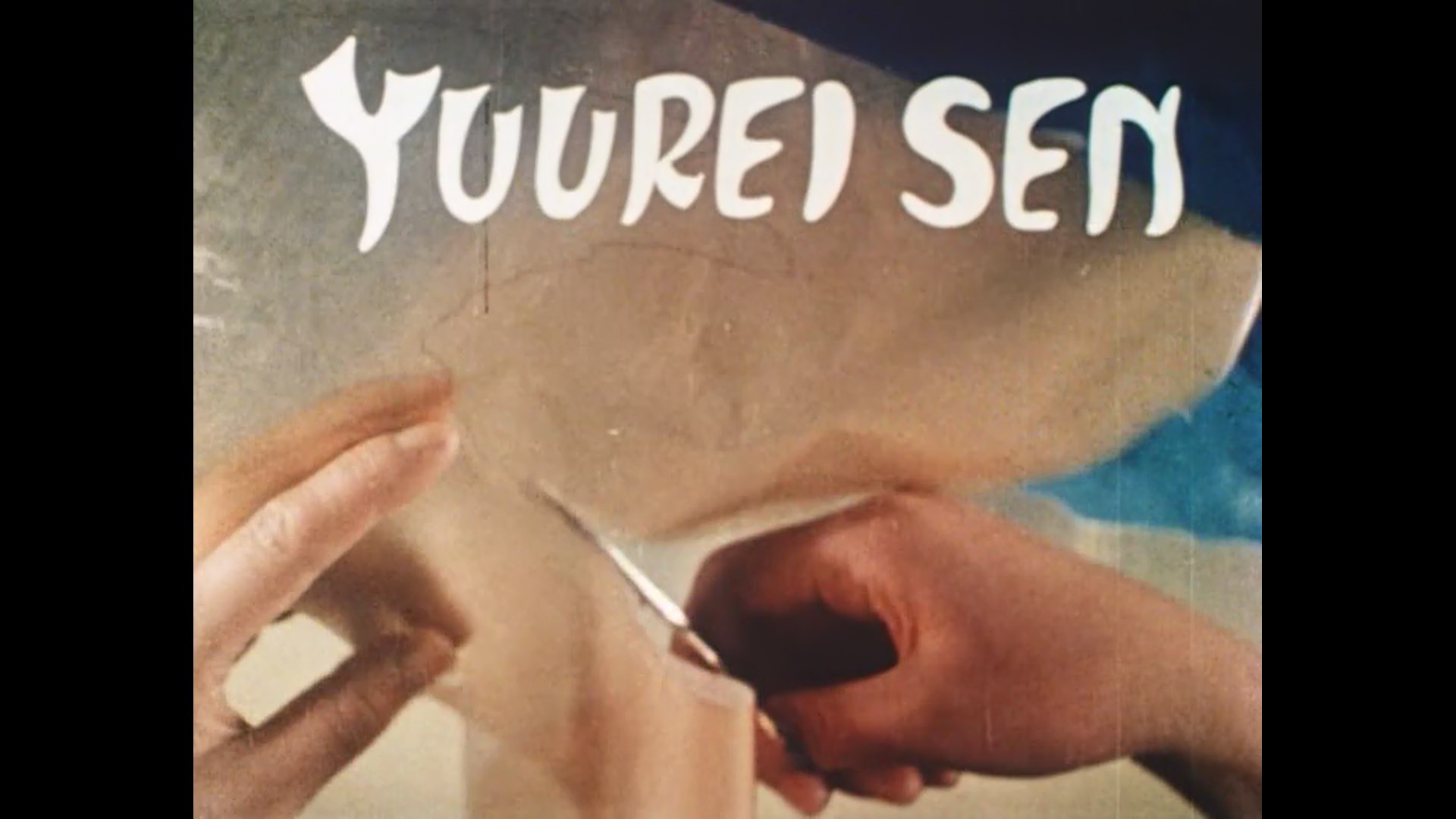

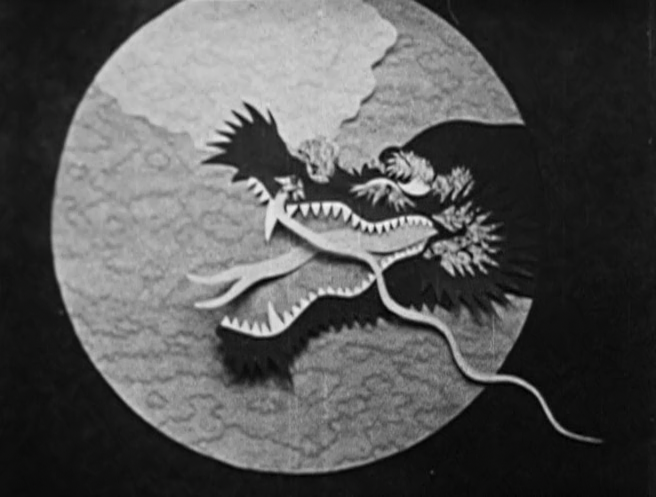

Ofuji channeled his interest in film towards animation since the start, even if his works didn’t quite resemble “anime” as we’ve come to understand it. Early test films like A Story of Tobacco combine cutouts with live action footage, whereas other films of his were fully silhouette-based – like his 1952 self-remake of Whale, which earned him recognition at the Cannes International Film Festival. However, it was in chiyogami animation that he first found his footing; most of his early works, including his professional debut Burglars of “Baghdad” Castle, were crafted with cutouts of this traditional, hand-screened patterned paper. Even though their vivid colors couldn’t come across the black and white projections, the texture that this technique gave to his works was unlike anything his peers were producing at the time. Hence why, shortly after his career had officially begun, the research studio he’d established changed names to become Chiyogami Eigasha. Ofuji had found his unique means of expression.

Noburo Ofuji animation reel compiled by Uga.

It’s worth noting that, perhaps as a consequence of having been born into a family running a phonograph recording establishment, another of Ofuji’s early innovations was adopting record talkies faster than any other Japanese animation creator. Which is to say that, before the expensive tech of projectors that incorporated audio became widespread, filmmakers like him simply played a record alongside their movies. To exploit all the new possibilities, many of Ofuji’s early films incorporated dancing sequences that had been synchronized with the music in those records. These techniques, alongside recurring themes in his works – like the moralistic fables or downright propagandistic intent that embody the sociopolitical climate of the time – make it easy to grasp Ofuji’s identity as a creator, much as he tried to innovate.

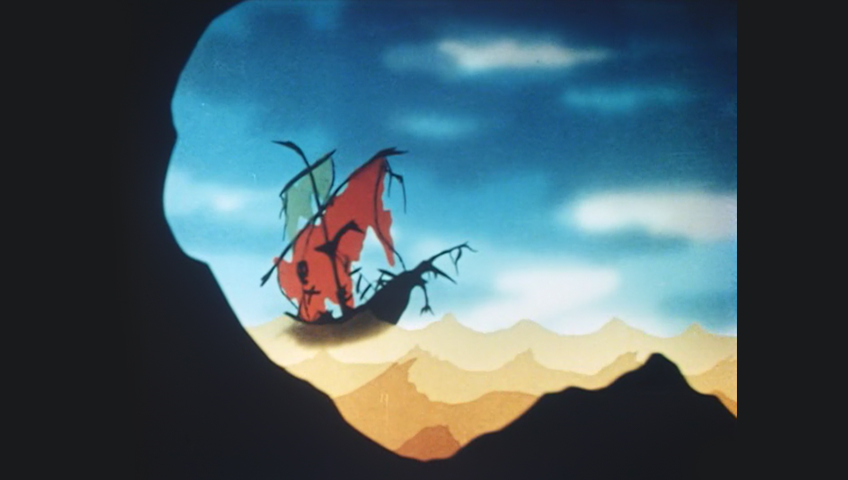

Unable to stay away from such a game-changer, Ofuji dabbled in cel animation during the 30s and 40s as well, much like other precursors of anime like Sanae Yamamoto. But frustrated over the lack of progression that the cel paradigm shift caused on silhouette animation and over the prohibitive pricing of celluloid – his austere childhood made him mindful of the economy of production, even after he gained international recognition – he decided to innovate in that field again. The solution he arrived to when thinking of how to cheaply fulfill his dream of making color silhouette movies was colored cellophane. The silhouettes he mastered before were able to invoke a mesmerizing atmosphere, a richer and more layered experience than ever before – as seen in the aforementioned Whale and his magnum opus, The Phantom Ship.

As a side note, if any of this has made you interested in Ofuji’s work, I greatly recommend checking out the extensive coverage of his career on the Japanese Animated Film Classics website; not only do they feature a more extensive look at his biography and filmography, they also offer extensive samples of his work, production materials, photos, and right about everything you could need as it was presented in the Noburo Ofuji: Pioneer of Japanese Animation exhibition in 2010. They’re an excellent resource for your classic anime needs!

Following Ofuji’s death in 1961 and with the help of his elder sister Yae, the Mainichi Film Awards honored his career with the establishment of Japan’s first major, still ongoing animation prize. A nice gesture in and of itself that was made much better by the profound respect for his creative philosophy, which can still be felt nowadays. After all, the Noburo Ofuji Award doesn’t just recognize excellent animated pieces – although the prize tends to go to titles that are great anime above everything else – but rather recognizes exceptional innovation. Maintaining that core idea was so important that, after the boom of massive anime movies Ghibli caused in the 80s, the Mainichi Film Awards added a new animation prize for standard excellence. The divide isn’t as clean as smaller experimental projects vs high profile hits (even a Ghibli movie like Ponyo managed to win the Noburo Ofuji award in 2008 for its original expression), but it generally allowed the original award to keep on honoring the most innovative works for anime altogether. The legend of an anime pioneer lives on through an award that highlights works that push the art forward in some way or the other, just like he did!

And in more precise terms, what does that innovation mean? Many things, and that’s the charm! While the idea of inventiveness (and the success at presenting those new ideas) makes the awarded pieces a cohesive bunch on a conceptual level, the actual works are as diverse as it gets. Among the winners we find titans of anime like Hayao Miyazaki (from Cagliostro to Totoro, even the Ghibli Museum exclusive Kujiratori) and Isao Takahata (Gauche the Cellist), which shouldn’t come as a surprise since the first winner was none other than Osamu Tezuka with his poignant anti-war statement Story of a Certain Street Corner. At the same time, they’ve also awarded many independent creators, from classics as early as Makoto Wada‘s Murder (1964) to short films as recent as 2015’s Datum Point by Ryo Orikasa, where a haiku takes the form of incessant waves, equating the impulse to resist writing to the plasticity of the plasticine used in this stop-motion animation. And despite being an award for Japanese animation, even nationality isn’t a be all end all – the likes of Aleksandr Petrov‘s paint-on-glass epic The Old Man and the Sea have won it despite lesser Japanese intervention.

And what if nothing fits their rigorous criteria for innovation in animation? Then the award’s left vacant with no hesitation, as shown by the 6 entries with no winner. Thankfully, we’re currently at a bit of a golden age when it comes to anime movies, so over the last three years we’ve seen fascinating commercial projects awarded for presenting something new. In 2016, it was the success against all odds by Sunao Katabuchi and his team to amplify the clear but resolute voice of a young woman amid the cruel loudness of war on In this Corner of the World that received this distinction. Last year it was Masaaki Yuasa‘s charming Lu Over the Wall, a showcase of Science Saru’s production synergy with the idea of enchanted water so eyecatching that they’re dedicating their whole new movie to that, that received the prize. And just recently we came to know that 2018’s winner of the Noboru Ofuji award was Naoko Yamada‘s Liz and the Blue Bird, a fundamental disruption of how image and sound interweave in anime.

It’s rare that you can point at a list of award winners and have that act as a blanket recommendation with an ethos of its own, but if you want a taste of Japanese productions that have pushed the boundaries of animation, by all means give a look at the Noburo Ofuji Awards – they’ll make for a memorable experience at the very least!

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

Really happy to read this thanks

It was a pleasure! It got me to rewatch the special Ofuji DVD and then a few of my old time favorites from the winners & others I’d overlooked… which in the end wasn’t really necessary for the post, but time well spent still.

Great article! Ofuji is definitely a creator that anyone interested in anime history should learn about. I’ve only watched three of his shorts prior to reading this article, all from the 1930s (Tengu Taiji, Chinkoroheibei and the Treasure Box, and Kokka Kimigayo), so I’m looking forward to checking out more of your links! Of the prize winners that I’ve watched, one of the most interesting lesser-known ones to me was 663114 from 2011, made by Isamu Hirabayashi in the wake of the Fukushima disaster. Not necessarily one that was “fun” to watch, but it was so striking that I’ve never… Read more »