Dororo – A Swordman’s Journey Through History

Dororo‘s one of the most critically acclaimed shows of 2019 so far, but the title itself is well over 50 years old. So what’s the story behind each iteration of the series, how did the historical context influence their creation, and what’s Dororo’s appeal in the first place? Let’s find out.

And don’t worry, no spoilers here!

Today’s story starts in 1967, with the publication of Osamu Tezuka’s Dororo. Though it never went on to become one of his most celebrated series, it features many elements that Tezuka fans, both at the time and nowadays, would immediately recognize. The tale begins with the ruthless feudal lord Daigo Kanemitsu coming across 48 sealed demons, to which he offers a part of his soon to be born son in exchange for enough power to rule all the lands. He then forcefully abandons the helpless child, who’s saved and raised by a benevolent doctor. Noticing the innate spiritual powers the child possesses to make up for all the parts the demons took, the doctor creates dozens upon dozens of prosthetics that end up forming the boy’s nearly immortal artificial body – sounds familiar?

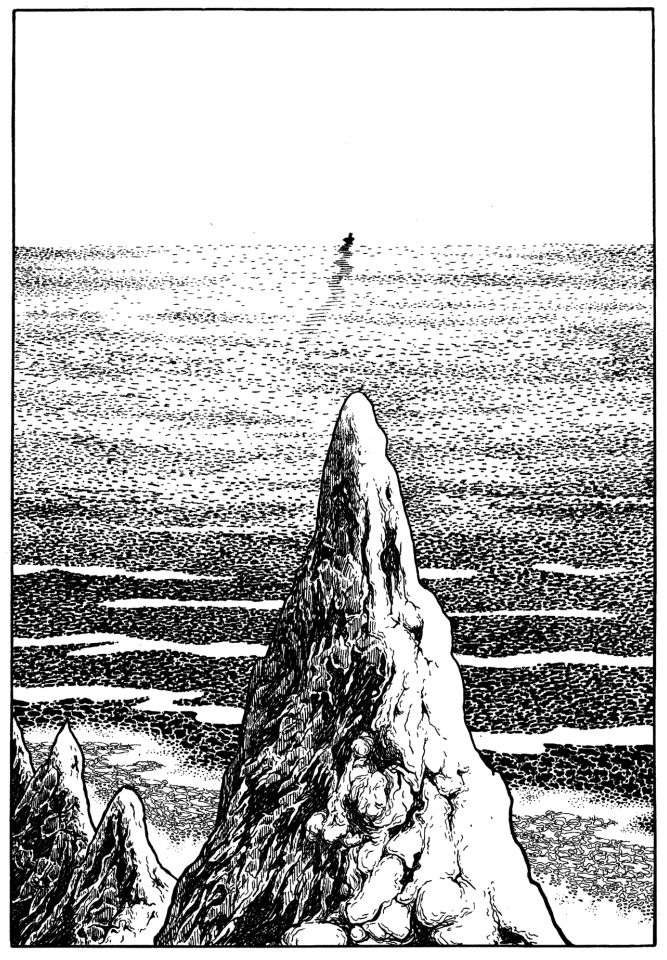

After taking up the name Hyakkimaru, he starts traversing the world looking for the demons that stole his entire being, as slaying them restores his human body one piece at a time. But he’s not traveling alone now: accompanying him there’s the brazen young thief this work is named after, Dororo. The wandering swordsman and his sidekick follow a well-trodden path, but that’s because that kind of setup works really well in the first place. Though they met by chance and didn’t see eye to eye at first, the two gradually grow closer as they travel through a Sengoku period land where the constant conflict has led to famine, death, and mistrust. Once again, the anti-war vibes in Tezuka’s work are rather obvious.

While the narrative might not turn heads by itself, the themes it explores are worth the price of admission. Tezuka’s usual messages are accompanied by other interesting ideas like the assertion that all of us are born incomplete like Hyakkimaru, and that it’s only through interacting with others that we can become whole. Discrimination of those who appear different than us (narratively equated to people with disabilities but easily applicable to other contexts) is another major theme the series is preoccupied with – not just the existence of those problems, but the kind of situation that enables those mentalities to flourish.

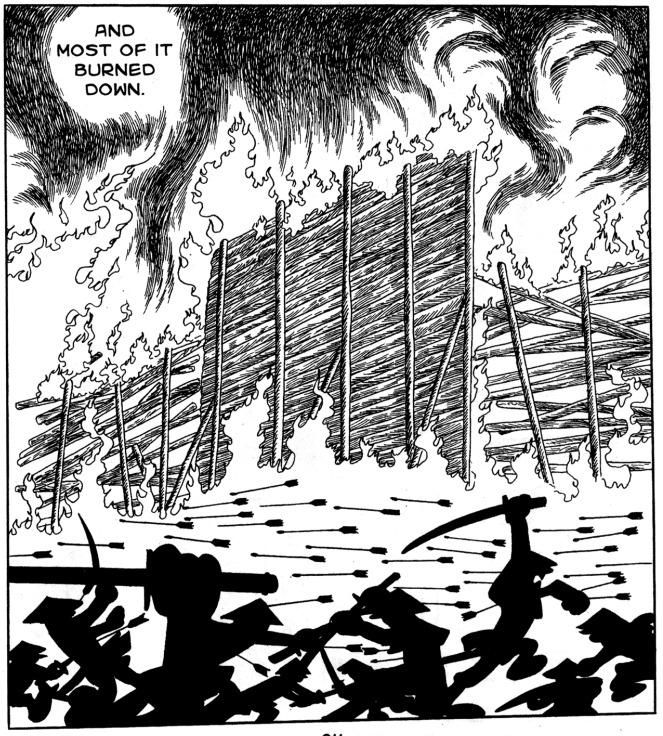

And of course, saying that his visual delivery of those themes has aged well isn’t nearly enough praise. The paneling and visual composition feel revolutionary now, let alone if you consider when it was originally published. At the same time, though, it’s hard to deny that Dororo’s got a bit of an identity crisis; the tone’s uneven as it was initially judged too gruesome and dark for a series aimed at kids, Tezuka revised the events in multiple instances, a few narrative threads are discarded, and in the end the story simply stops… twice, since even the second serialization that followed the TV anime wasn’t enough to bring the narrative to a complete closure. All things considered – and especially taking into account the short length – I encourage you to give it a read, but keep in mind that it’s an imperfect piece.

Those drawbacks don’t stop me from recommending the series, just like they didn’t stop an anime adaptation from happening back then. You might think this means it’s time to jump to April 1969 for the broadcast of the TV series, but first I’d like to take a quick stop slightly over a year before that. The Dororo pilot film that was pitched to investors was finished in January 1968, and not only is it available, but it also showcases fascinating differences with the actual TV series that tell us about the staff’s vision and what was enforced on them.

The timing of the project was tricky in the first place, as Tezuka was in the process of leaving Mushi Production to found Tezuka Production to better manage his properties. In spite of that, a team was assembled at MushiPro to create a teaser of what a Dororo anime could be like. The chief director was Gisaburo Sugii, who had recent experience leading a production after handling 1967’s Adventures of the Monkey King, and was plenty acquainted with Tezuka’s idiosyncrasies after working regularly on Astro Boy. The rest of the team included Hideaki Kitano as animation director, Isao Tomita as the composer, Hachiro Tsukima in charge of the art, and Yoshitake Suzuki on design duties. All of them would reprise their roles for the TV series, so you’d assume that the two would be rather similar, but nothing further from the truth.

If you look at the pilot by itself, the results of their work aren’t all that surprising. The short film contains a couple of snapshots of early events to give a taste of Dororo’s tone. The obvious caveat is that Tezuka’s visual storytelling is nearly impossible to match, much as they tried, so the delivery doesn’t have the same oomph despite doing a satisfactory job at capturing the essence of the series.

Things become a whole lot more interesting when you compare it not just to the source material but to the proper TV show that followed it up, however. The first major difference becomes apparent as soon as the first shot: while the pilot was in color, the TV show is a black and white production. Though B/W anime wasn’t quite extinct at the time (Umeboshi Denka started that same week for one) they’d become a rarity, even more so if there was a precedent for the studio and the very same title of color production.

This is explained by the Osamu Tezuka website as a matter of budgeting, and while that may be true to some degree, it definitely doesn’t paint the full picture. Reportedly, the sponsors who were shown the pilot film said that seeing those colorful splashes of blood during dinnertime with the family would be unpleasant, to which Sugii responded with “understood, so it’d be alright to do it in black and white right?” And if that sounds somewhat sarcastic, look no further than the fight against bandits in the first episode: exactly the same as the pilot (to the point of reusing assets) save for a noticeable redesign for Hyakkimaru, a cute dog accompanying him to make things more family friendly… and then a slaughter that feels more visceral than the original, since the evocative splashes of color were replaced by profuse bleeding.

And that about sums up the approach of the show as a whole. Sugii and his team appear to have listened to some producer demands to create a more marketable product, but then ran with their vision anyway, even if it conflicted with that. Though the most extreme body horror from the manga isn’t replicated, the show still features one gruesome battle after the other, and no amount of puppies can mask that. While the loss of the beautiful color work from the pilot was a pity, some horror scenes make excellent use of the monochrome palette. The title as a whole feels heavier, as if it were haunted by a demon that stole an integral part of its body like Hyakkimaru.

Calling the TV show that resulted from their efforts a mixed bag seems like a fair assessment. In its favor, it has the character dynamics that always worked, plus those delightfully ominous horror vibes boosted even further by Tezuka’s exceptional design work. If you were presented with his original creatures and monsters whose legends have been told for hundreds of years, chances are that you wouldn’t be able to tell them apart, since he was the kind of prodigy who’d make up beings that you’d believe are backed by genuine folklore.

I’d go as far as calling Dororo (1969) somewhat historically important too, as it was the first TV anime in the block that’d eventually become the legendary World Masterpiece Theater; though it was Moomin after it that established WMT’s identity of basing their tales in foreign source material, Dororo can always boast about marking the start of its history under the name of Calpis Manga Theater.

And yet, the cons might outweigh the pros in this case, at least if you judge Dororo (1969) as an adaptation. Sugii’s original pilot already made it clear that they couldn’t quite replicate Tezuka’s memorable visual delivery, but even the narrative’s a bit confused. The change in certain character behaviors has questionable effects – look no further than the final moments between Hyakkimaru and Tahomaru, where solemnity and tragedy are replaced by spite – and above everything else, the problem is that the source material’s identity issues are multiplied tenfold in the small screen.

Nothing exemplifies this better than the big turn the series takes with episode 14: Sugii moves to a less involved role as Kitano takes up on series direction, and the show as a whole is renamed to Dororo and Hyakkimaru, which sums up the change in priorities. Entire arcs revolving around Dororo are discarded in favor of original episodes about slaying demons, including a definitive closure for the co-protagonist’s narrative which doesn’t even pack as much of an impact as the manga’s non-ending. Not a terrible show by any stretch, and quite the interesting project overall, but I don’t believe it’s aged as gracefully as the source material.

Considering all the issues it had, the modest popularity, and some unfavorable circumstances (like the prejudice against B&W works and terminology regarding disabilities that came to be seen as insensitive making the prospect of rebroadcasts unenticing), it’s no surprise the property stayed mostly dormant for decades. A forgotten PS2 game in 2004, a live-action take in 2007, and some comic spinoffs more recently showed that Dororo wasn’t dead, but no one could have expected the current multimedia campaign captained by the TV anime Dororo (2019). Or could they?

If you’ve been paying attention to the anime industry over the last few years, chances are that you’re aware that overproduction is one of the major problems that it’s facing. We’re not going to get into how that causes unhealthy habits in both production and consumption of anime today, but we’ve got to talk about a consequence that happens to be relevant to this case: anime is running out of fresh source material.

I don’t mean that literally, of course; there’s always going to be countless unadapted manga (and novels for that matter), because the economic barrier to getting a comic published and an anime production rolling are orders of magnitude apart, and this is a cowardly industry to boot. If you limit the candidates to the titles likely to grow a decent following, though, then you realize that the pool of current works that clear that bar’s done nothing but grow shallower because of the volume of anime produced. Add to that the fact that we’re in an era where nostalgia exploitation is all the rage, and the solution’s clear: anime’s looking back to classic titles to quench its insatiable thirst. One of the main objectives of this piece was to detail how the context of each iteration in this franchise affected the work, and in this case, it’s as fundamental as it gets – Dororo (2019) owes its existence to anime’s current climate.

Very much in Dororo tradition, the 2019 series also featured a pilot short film totally unlike the show that followed it. It was made by Takuji Miyamoto, who channeled the rage that was always present in the series into something quite memorable.

Keeping in mind that projects like this are a fortunate consequence of an otherwise troublesome situation in the industry is important, but it’s not as if that disqualifies this new Dororo series from being a damn good anime. And achieving that, which I believe it has so far, wasn’t a given. Considering how long it’s been since this story was originally written, a large update to make it easier for younger generations to get into the series was bound to happen. A complete reimagining (like DEVILMAN crybaby‘s, and to a lesser degree Banana Fish‘s) would have been impossible for a period piece like Dororo, so instead, they did their best to adapt that same tale to modern sensibilities. I know, that sounds worrisome.

But what does that entail, exactly? The pace and density of storytelling in animation have increased throughout the years, and modern audiences tend to want detailed explanations about the motivations of all characters and worldviews that aren’t so black and white. Fair demands, but there was value to the elegant straightforward nature of the original, and you don’t achieve more nuance simply by adding tons of exposition. Fortunately, the staff seem to be perfectly aware of that, hence why all the changes are very deliberate and focused; giving a shocking backstory to the doctor isn’t just an attempt to give more texture to the character, but also another reminder that it’s impossible to live one’s life unaffected within a society drowning in war and conflict.

Similarly, Hyakkimaru’s journey to recover his real being is forcing him to come to terms with the tragedy that surrounds him. Reclaiming his skin and sense of pain is immediately followed up by being cut and hurt, and the first thing he hears after growing real ears is a horrified scream. Even smaller narrative changes, like initially depriving Hyakkimaru of the ability to communicate, seem to have clear goals – forcing Dororo to take a more proactive role evens the field in their relationship, which should be well received considering future developments. Dororo (2019) is so far a smart update built upon solid foundations.

When it comes to its production, Dororo (2019) is also an interesting mix of new and old. Though you’ll only ever see MAPPA’s name being brought up, the truth is that it’s a co-production in fairly equal terms with Tezuka Production; the former produced episodes 1-2 & 5-6 so far, while the latter handled 3-4 & 7, so in the end we’re expecting a mostly even split with MAPPA doing a bit more simply because of their much larger size. And leading those efforts we find series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario. Kazuhiro Furuhashi this time. He might be best known for his work on Mobile Suit Gundam Unicorn nowadays, but if anything it’s 90s adventures of his like Rurouni Kenshin and Hunter x Hunter 99 that this should immediately remind you of. I have to admit that seeing him work alongside some iconic figures of 80-90s action titles like Shinsaku Kozuma makes the whole show sorta reminiscent of an era that’s long over. They’re not trying to channel the truly old-school aesthetic by any stretch, but its nostalgic flair is genuine.

If I were to highlight one aspect where the intertwining of anachronic elements and modern mentalities and techniques is particularly on point, it might be the art direction. At first glance, the muted colors might not seem as attractive as previous Studio Pablo offerings. And they’re not, but that’s the point. The mostly traditional paintings that serve as Dororo‘s backdrops often appear lifeless – not in the sense that they’re inert, but rather that they feel as if life had been stripped away from them because of the neverending conflict. If anything, the more striking splashes of color are tied to the most horrifying events, as if they were stained by blood like the lives of so many people. Beauty still exists in this world, but it’s often inevitably tainted by tragedy.

And that’s where we are right now, wondering if Dororo (2019) will make an uplifting statement that lives up to its poignant condemnation of conflict, or if we’re in for a downer of a journey. Either way though, the story of this property throughout the years is already quite the interesting one, so I hope you enjoyed following the swordman and the thief’s footsteps as much as we did!

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

THANK YOU! Dororo’s a badass anime (reminds of my favorite Sword of the Stranger) and reading the history behind it was cool. The comparisons between the old and new animation are interesting too.

BTW a bit offtopic but what’s your favorite anime this season??

Mob Psycho’s the one I find most fulfilling, be it on an emotional level or as an animation fan, and Kaguya-sama’s the most fun I’ve been having with current anime. Dororo’s now joined the group of shows I simply enjoy a lot, which is larger than expected. Won’t complain!

Besides the various storytelling issues you mention, I’ll also say that one reason the original Dororo TV series hasn’t aged gracefully is the extreme jankiness of the production. Between the dominant stiffness and lack of movement, clumsily executed loops and reused cuts, and lack of continuity or sense of space between successive shots, it’s obvious just what a shoestring production it was. There’s still some effective imagery, particularly in some of the backgrounds, and I don’t want to be too hard on a studio that was still figuring out how to do this ultra-budget TV anime thing. But it gives… Read more »

Yeah, it feels like a compromised production on a fundamental level at a time when anime as a whole wasn’t great at cutting corners yet. That’s why I said that the official take being that things like the loss of color were due to a budgeting issue likely have some truth to it, regardless of the obvious creative disagreements. Everything about it gives off the feeling that it ended up being a smaller project than the people behind it intended to.