Digimon Adventure: 20 Years Of Sincere Mamoru Hosoda Films

Mamoru Hosoda’s theatrical career started 20 years ago with the Digimon Adventure short film, so this is a good opportunity to celebrate this unusual production and the evolution of one of anime’s most sincere storytellers. Enjoy!

We often write profiles of creators that anime viewers at large don’t have a confident grasp on, be it due to their eclectic style or because they haven’t been around for long enough for anyone but the hardcore fans and in-the-know industry members to notice them. It makes sense for a site focused on the production side of things like this one to give preference to overlooked voices, even as we tend to limit ourselves to the commercial animation sphere.

And Mamoru Hosoda is many things, but an obscure anime creator he is not. His immense commercial success is easily quantifiable, and the enthusiastic critical appraisal doesn’t lag behind at all; with his recent Academy nomination for Mirai, he’s become one of the few non-Miyazaki anime directors whose existence’s been acknowledged by English media, which is a depressingly tricky bar to clear. It’s fair to say that he’s not in need of signal boosting by a niche website. If you’re reading this, chances are that you’re aware of who he is.

On top of that massive recognition, Hosoda’s in the running for the anime’s most sincere creator. He’s devoted to a consistent ethos with children as the centerpiece and has openly admitted that his mindset when directing’s reshaped entire projects. It’s no secret that the bitterness in One Piece: Baron Omatsuri and the Secret Island came from Hosoda’s frustrated attempt to direct Howl’s Moving Castle at Ghibli, which turned a rather silly scenario pitch into a darker affair. Right after returning to Toei, and in his first major project after leaving them, the most iconic imagery in his works reflected his pondering about which path to follow. In more recent times, his films have been born from developments in his life to begin with – Wolf Children’s tale of motherhood after his own mother died, a father’s struggle in the form of The Boy and the Beast once he became a parent, and the downright autobiographical Mirai just last year.

That applies to his best known visual quirk as well. Kaguya-sama Love is War’s popularity has gotten people to talk about kagenashi: an approach based on flat visuals with no shading nor highlights, which artists use for a variety (thematic, aesthetic, technological) of reasons. And as we mentioned in passing during our first Kaguya-sama write-up, Hosoda argues that kagenashi’s a cornerstone of his philosophy as a storyteller; since he makes anime with children in the spotlight – both as main characters and in the audience – he wants to convey feelings with no subterfuges. Kids’ minds exposed clearly, and thus without complicated shading getting in the way. Despite being an heir to one of anime’s most ornate directorial bloodlines, Hosoda’s come to value clarity as a key aspect. It’s not that he deals with simple ideas (if anything he’s a fan of ambiguous emotions), but that he’s very invested in accessibility so that even the youngest viewers can perceive the characters’ and sometimes his very own dilemmas. Hence why it’s rather easy to get what he’s all about, even when it comes to his workflow.

So, why are we writing about an older work of his again, if he’s supposedly that easy to grasp? Because we like him, because you like him, and because Digimon’s celebrating its 20th anniversary right now. And that means it’s been two decades since Hosoda’s first movie.

Digimon posed itself as an evolution of the likes of Tamagotchi: virtual pets you didn’t simply take care of but could also use to battle your friends. A more aggressive edge to the 90s mascot craze that influenced the design philosophy of the franchise since its inception… though truth to be told, it doesn’t seem like they had a properly defined vision until Digimon‘s multimedia expansion. After multiple revisions of the toys, a manga one-shot, and other mostly forgotten enterprises, Bandai kicked up everything a notch in early 1999 with the release of Digimon World for the PS1 and an anime alongside Toei Animation. And it’s precisely the latter that we want to pay homage to, as a curious production that marked the start of a beloved director’s theatrical career.

Chances are that your mental image of an anime project meant to promote a property with aspirations of becoming a merchandising behemoth is restrictive, with countless guidelines set before the creators come into play. And while that’s true in many situations, it doesn’t necessarily mean that they’re meticulously planned or that producers know what they want in the first place. As mentioned by Hosoda himself, Digimon Adventure: The Movie (not to be confused with the embarrassing western mishmash) was in the works before the TV show was pitched, even though it’s now seen as nothing but its prologue. There was no real narrative to use as a springboard either, nor was there an established cast of characters; though the looks of certain characters like protagonist Taichi were determined by cross-media obligations with series that preceded the anime like Digimon Adventure V-Tamer 01, it was Katsuyoshi Nakatsuru‘s designs that served as the starting point for the cast rather being the visual realization of ideas that were already agreed upon.

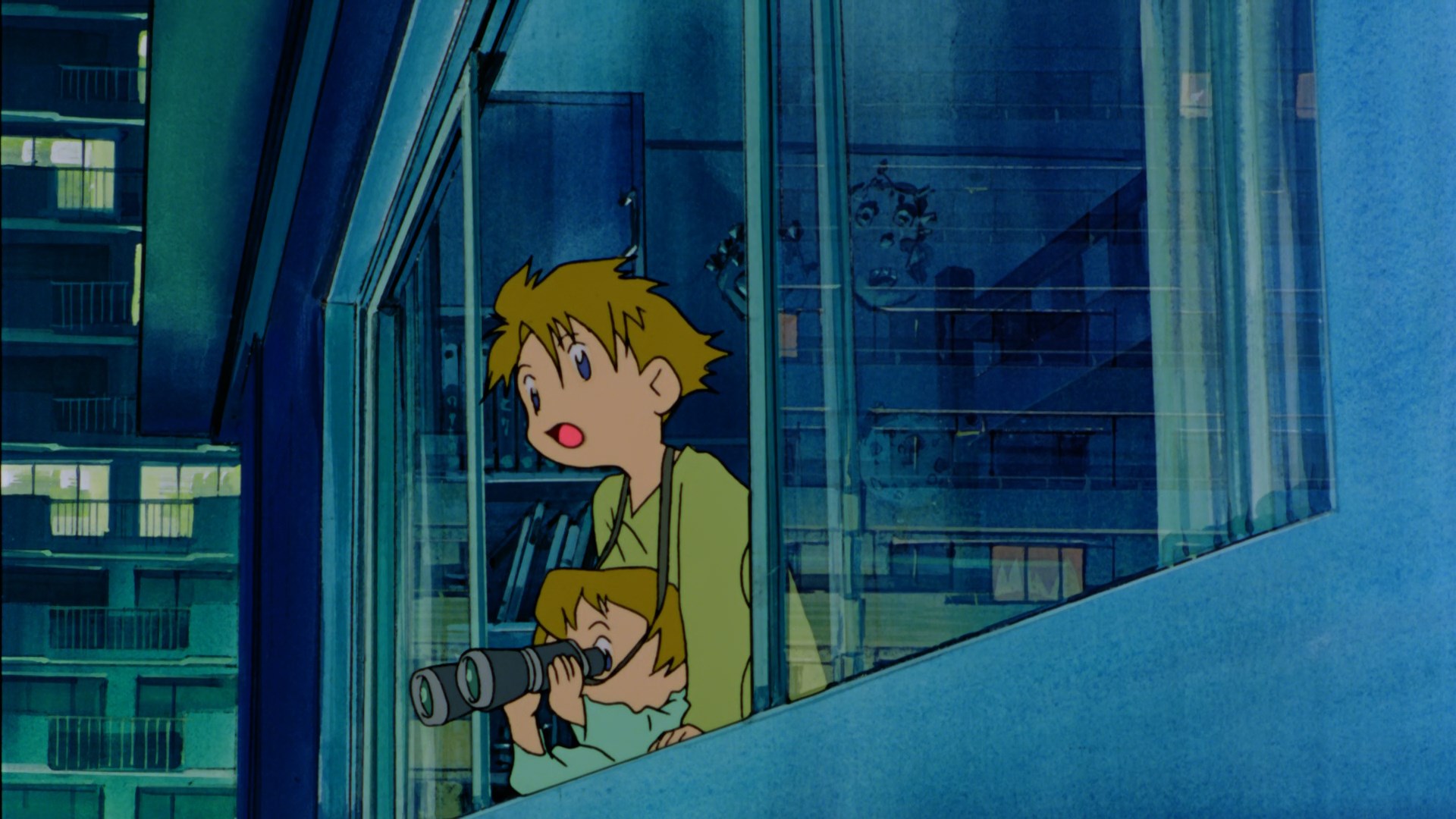

Execs would vaguely nudge the staff in certain directors and sometimes veto their wildest ideas – we’ll never have Hosoda wacky Digimon comedy set in the 60s and led by Taichi’s dad – yet never offer constructive guidance. This kind of situation, where creators are freely creating without actual freedom, is rather common at Toei Animation due to the kind of mainstream projects they deal with, but Digimon took it to a rather extreme extent. With not one but two groups of creators left to their own devices, it’s obvious how a big tonal gap could open between the two Digimon Adventure anime in spite of the mandates to fit everything within one same continuity. Since the movie was due to be screened as a short piece within Toei Anime Fair 99 just one day before the broadcast of the TV series, Hosoda and company had to condense the thrill of a kaiju movie down to a few minutes while also introducing a series that wasn’t in the cards when pre-production started. A tricky goal that turned out… pretty well, actually?

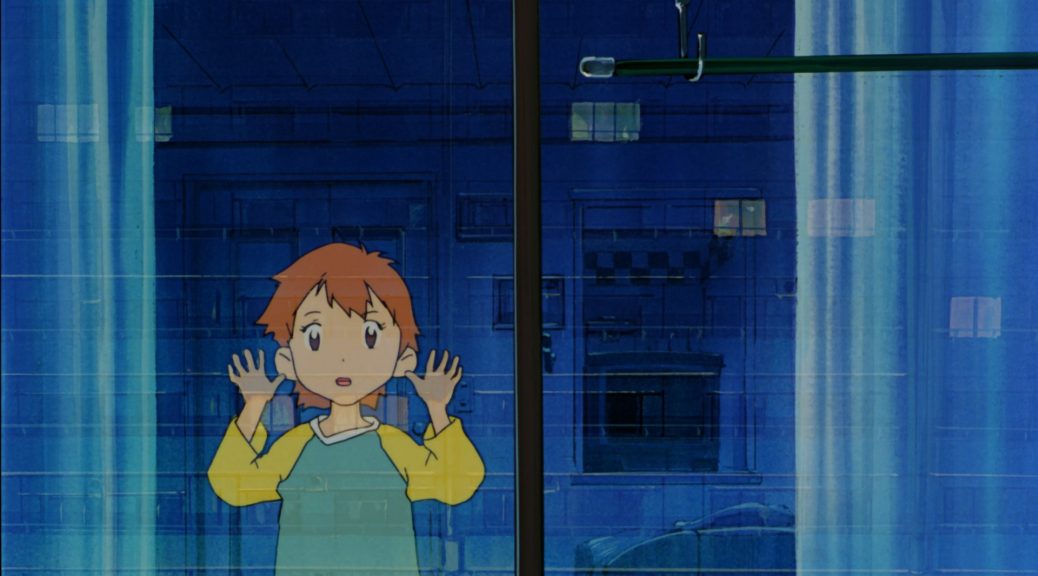

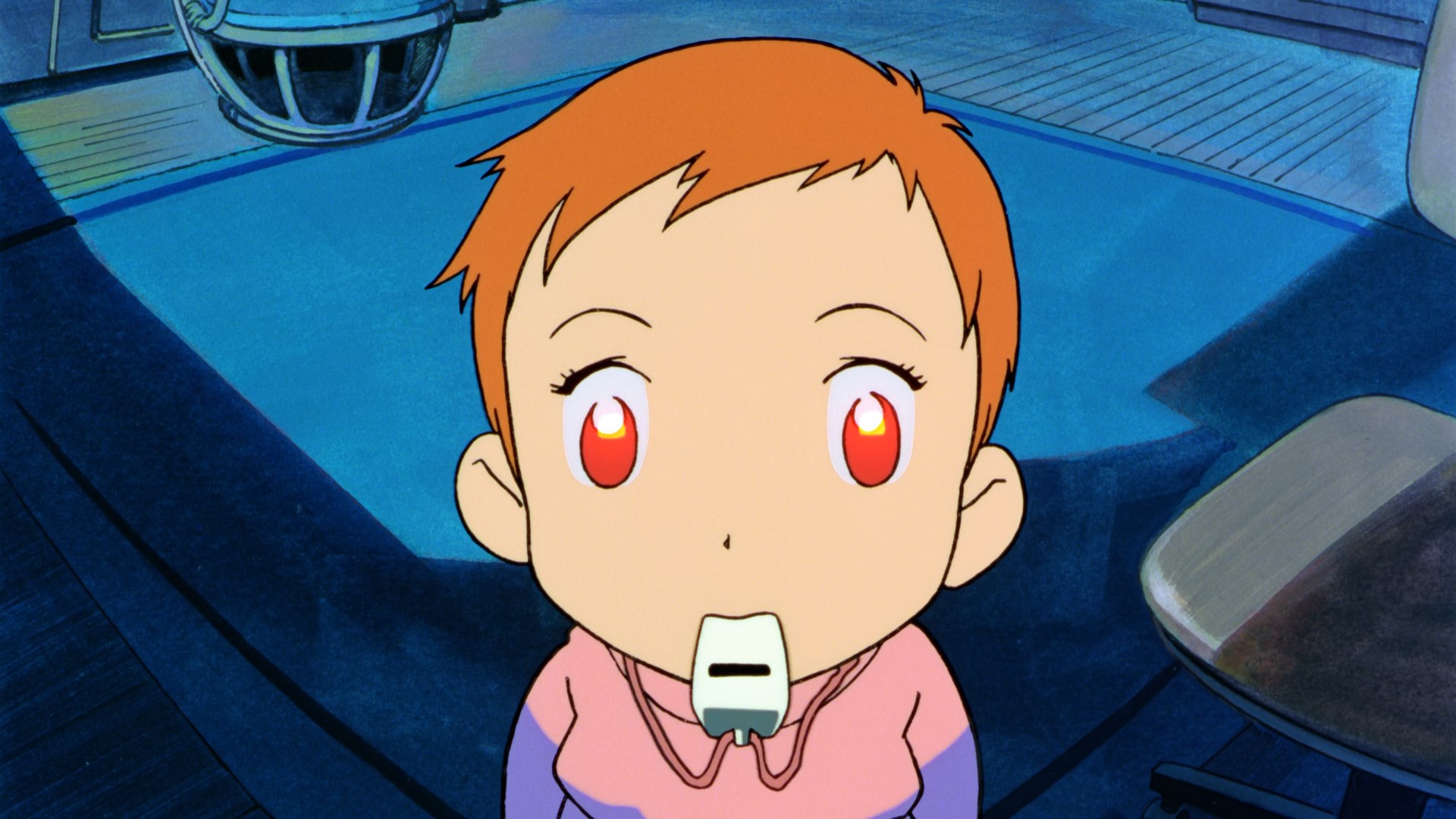

The first aspect that stands out in Digimon Adventure: The Movie, especially in contrast to its televised sibling, is the Digimon’s fierceness. This franchise’s not one to shy away from dark plotlines and scary villains, but the ferocity of creatures we’ve assumed to be benevolent is presented in such a natural, matter-of-the-fact way that it’s simply chilling. Though this short film is devoted to the friendship bonds between Taichi and his fated partner, the source of the conflict isn’t so much the external menace in the form of Parrotmon, but rather Big Agumon’s ambiguous (a)morality, these creatures’ dangerous innate instincts to fight, and how damaging their mere presence in the human world is. The hero’s ally is larger, it loses the ability to communicate verbally, and there’as something very palpable to the destruction it causes. Quite the animated debut for Bandai’s marketable creatures. Yukio Kaizawa and Chiaki J. Konaka would later pick up on some of those ideas for Digimon Tamers, but nothing reached the animalistic dread that transpires in the franchise’s big screen debut.

That fearsome side of the Digimon is seen at its grandest during the fight between Red Greymon and Parrotmon, in no small part because of the exceptional animation. The movie’s non-verbal communication is carried by the articulate acting throughout and, when the action hits, it does so with tremendous authenticity. Children’s first experience with animated Digimon fights was a visceral showcase of physicality from a technical standpoint, and damn horrifying to watch in plain terms – something very deliberate considering the tone. Regular Hosoda allies like Takaaki Yamashita (supervisor for the first of many Hosoda films) and Hideki Hamasu (ace animator of sorts, a role he’d also reprise in multiple occasions) are joined by people like Mitsuo Iso who need no introduction, but it’s the hyperrealism in Hisashi Mori‘s animation that anchors the battle to reality in such hair-raising way.

When judged as a Mamoru Hosoda movie rather than a Digimon one, this short film’s also interesting as the beginning of a stylistic shift. As you might know, Hosoda’s mentor was none other than Kunihiko Ikuhara, as well as the sadly undervalued Shigeyasu Yamauchi who served as a reference for multiple generations of directors at Toei Animation. They had a huge aesthetic influence in Hosoda’s works as episode director at the studio, be it with the weaponized solitude he learned from the latter or the former’s usage of intricate architecture for framing purposes (do yourself a favor and watch Hosoda’s contributions to Ashita no Nadja). He also embraced a very Ikuhara-esque feeling of rhythm, with that same calculated repetition but more of a focus on the role audio can play over familiar visuals; that’s pretty clear in Digimon Adventure: The Movie, whose only BGM is a loop of Bolero de Ravel that Hosoda managed to sell both as a grandiose tune and a punchline for a pooping creature.

It’d be a lie to claim that Hosoda moved away from his mentors’ teachings, but there’s a gradual evolution from Digimon onwards as he began to find the kind of stories he wanted to tell and adapted his repertoire to his own tone. The usage of shots framed with the same angle (同ポ) remained, but he began ditching that expressionist edge that’s so easy to associate to Ikuhara with a much more clinical approach to the layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists.. The recurring everyday snapshots that have served as the backbone of Hosoda’s movies for years couldn’t have been possible without the likes of the aforementioned Takaaki Yamashita, capable of drawing many detailed, true to life layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists.. Hosoda’s latest movie Mirai goes as far as structuring its storytelling around a house designed by a real architect, which feels like the culmination of something he started in Digimon Adventure: The Movie with its apartment complex setting. Even the idea of containing the action there took into consideration children’s perception of the events, already showing his dedication to creating works that can resonate with both parents and children whether they’re able to pinpoint why or not.

And as far as I’m concerned, that’s something to be admired. There’s no shortage of people who miss Hosoda’s more experimental works and sharper edge (his style peaked within Doremi as far as I’m concerned), and while I understand that feeling, I can’t bring myself to feel anything but happiness when I see a creator so devoted to honesty. So happy 20th anniversary Digimon, and happy 20 years of Mamoru Hosoda theatrical projects!

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

Thanks for the article!! I think this is a pretty good description of Hosoda’s distinct charm!

The Digimon Adventure movie left a strong impression on me, even though I had watched it in my late teens, years after I grew out of my Digimon phase. It probably wasn’t a coincidence that I later developed an even stronger attachment to Summer Wars. I’m hoping to show the film to my friends soon and perhaps they’ll like it just as much as I did!

All Hosoda Digimon’s got a pretty universal appeal that extends beyond any attachment to the franchise, which I feel was true of all his best works within other people’s series at the time. Rewatching a bunch of it has left me wanting to revisit even more of it and try to come up with an excuse for another post, lol. Toei’s got quite the blessed new generation at the moment, but the emergence of figures like Igarashi and Hosoda with mentors such as Kaizawa, Ikuhara, and SatoJun still around might have been their golden age (as long as you separate… Read more »

i’m currently rewatching utena as part of a big ikuni marathon getting ready for sarazanmai, and it’s the first time i’ve rewatched that series since i started getting into sakuga stuff, so i got very excited seeing akemi hayashi and mamoru hosoda’s names prominently in the credits of some of the most visually striking episodes. those storyboards… there really is just something about hosoda’s work… his unflinching handling of messy emotions plus the way he values children’s perspectives is something i wish more directors had. i’m so glad digimon got his work attached to it, and i’m looking forward to… Read more »

Returning to Ikuhara’s work is very fulfilling not just because you’re bound to find new aspects to appreciate (aesthetically, thematically, both at the same time!) but because of his crazy good scouting. Always fun to look at the credits of his past works and realize how many people made it big and became directors that people pay close attention to now. I think I’ll try to squeeze in a Penguindrum rewatch before Sarazanmai too, since I’m too busy to watch it all again but it’s been too long since I last saw that one.

I really admire Hosoda personally even after his departure from TOEI but we can see how his time in TOEI left him with quite impact of directing the films after that. Summer Wars was still my favorite movie with its blatant recalls on digimon stuffs he worked before (Bokura no War Game), the gags, the fighting, etc it’s all very digimon-ish and it’s not something bad at all . It feels like watching digimon on something that is not a digimon. I really wish there is a tribute from TOEI to Hosoda for his precious works in the franchise for… Read more »

Thanks for this article!!! I actually had no idea that Mamoru Hosoda was the head guy behind one of my absolute favorite childhood movies to this day, so I learned something new today! I don’t appreciate the dig at the Western dub of Digimon the movie tho (unless I misinterpreted the comment about the “not to be confused with the embarrassing western mishmash” bit)….it’s the one I grew up with and I love how wacky and lighthearted it is, even if the original dub may be different the English cut will always have a fond place in my heart. I… Read more »

Haha it’s not so much the English dub (never saw it!) but the “localization” of the movie, which is what made it to Europe as well. They merged /three/ different Digimon pieces after initial plans of fusing Hosoda’s two films (already a very questionable thing to do considering the different tone) and the result’s just a confused mess. On the bright side, the Angela Anaconda intro’s only gotten more hilarious in retrospect just because of how bizarre that was.

I’ve always liked that “kagenashi” style without actually knowing it had a name. But I think the reason it works so well in this production and others of that period is because of the impecable color management some of these late “cel based” movies had, specially notable in ovas of the 90s and late 90s like the Jojo OVAS or Kenshin OVAS, to cite a few. Do we have any knowledge of how they approached color in the 90s? I’ve read that color correction at that time was limited to basically shooting stuff in different kinds of film and things… Read more »

The thing is that there used to be some… I don’t want to say “accidental” successes because it was a known factor that the staff tried to account for (the method you mentioned being one of those ways), but there are more than a few instances where the difference between the colors used in the cels and the footage people saw made the palette so much more memorable. Look at CCS’s latest master that’s supposedly much more faithful to the cels for one – it lost a lot of the liveliness that I associate with the show. Nostalgia aside, it’s… Read more »