20 Years Of Ojamajo Doremi: The Ideal Kids Anime Grows Up With Its Audience

Ojamajo Doremi became a formative experience for a whole generation. An impossibly daring team with a perfect overlap of young and veteran talent at Toei accompanied kids across topics no other anime would tackle with such maturity. 20 years later, they still do.

Ojamajo Doremi was a formative experience for the entire demographic of people who’ve actually seen Ojamajo Doremi; which is to say, a whole generation of people in Japan, and much spottier coverage overseas. I’m grateful to have grown up with a localization that hit it so big it permeated into mainstream culture somewhat, but that also means I’ve always struggled to convey how important the show was to my English-speaking acquaintances, as most of them either never came across it or had unfortunate short experiences with a dodgy dub. That said, some of the biggest fans of the series I know are friends who tried to address that by watching the series as adults, so don’t resign yourself to thinking that you’ve missed the Ojamajo Doremi train if you never saw it as a child—like all the greatest kids anime, it’s got something for everyone.

When trying to explain exactly what that something was, there’s the risk of missing the forest for the trees, to laser-focus on Ojamajo Doremi’s differential factor so much you forget what most of the series was actually like. And that’s joyful. From its fun animation philosophy—cartoony expression that retained character specificity—to the attitude of the titular main character, the self-proclaimed unluckiest pretty girl who remained a fundamentally good and positive person, Ojamajo Doremi always managed to find time to cheer you up. Even as it began approaching heavier topics, the show made sure to make them palatable to its young audience; not by making light of those harsh situations, but instead creating oases of respite whenever possible. Episodes that could shatter your heart would still sneak in a pat on your back, be it as an ultimately uplifting conclusion or a well-timed amusing sequence. The reason I, like many other people, remember Doremi as a cheerful anime despite the plethora of painful subjects it tackled is that its team went out of their way to leave that sweet aftertaste for kids and parents alike.

In retrospect, it’s that mindfulness of the audience and the ability to actually act upon that made Ojamajo Doremi what it was. It’d be easy to vaguely chalk it all up to the skill of the team behind the show, but if you want to truly understand why such a project was possible and why no one’s been able to mimic it ever since, it’s worth stopping for a moment to think about its context. Because for starters, Doremi happened at exactly the right time to feature the most brilliant overlap of Toei Animation talent across different generations, with a crucial helping hand descending from above too.

Although Kunihiko Ikuhara—now considered the most renowned Toei-trained director from that era—had already distanced himself from the studio at the time, his greatest pupil Takuya Igarashi was right there to handle a new series for the very first time; his true directorial debut having been, of course, a Sailor Moon series he inherited from Ikuhara. Igarashi captained an ambitious, wildly creative team where other youngsters got their breakout. Tatsuya Nagamine, who’d eventually direct another generational magical girl project in HeartCatch Precure! and is currently giving an unheard of makeover to One Piece, was also thoroughly trained during Doremi, a project he holds very dearly to this day. Even character designer Yoshihiko Umakoshi, a living legend who at the time already had a few projects under his belt, can look back at Ojamajo Doremi as a transformative production for him. If you haven’t seen the show but have enjoyed later projects involving any of these parties, chances are that you’ve actively benefited from Ojamajo Doremi’s existence.

As exciting as fresh talent can be, Toei made sure to surround them with veterans who knew how to tackle the conceptual and management challenges. No one embodies that better than Junichi Sato and Shigeyasu Yamauchi, co-series directors for the first and second seasons respectively. The former was already well on his way to becoming a kids anime institution at the time, and while the latter has never received as much widespread praise as he deserves, his uniquely evocative isolation makes him the most influential Toei figure since their Douga era; in short, Igarashi and company could have had no better bodyguards.

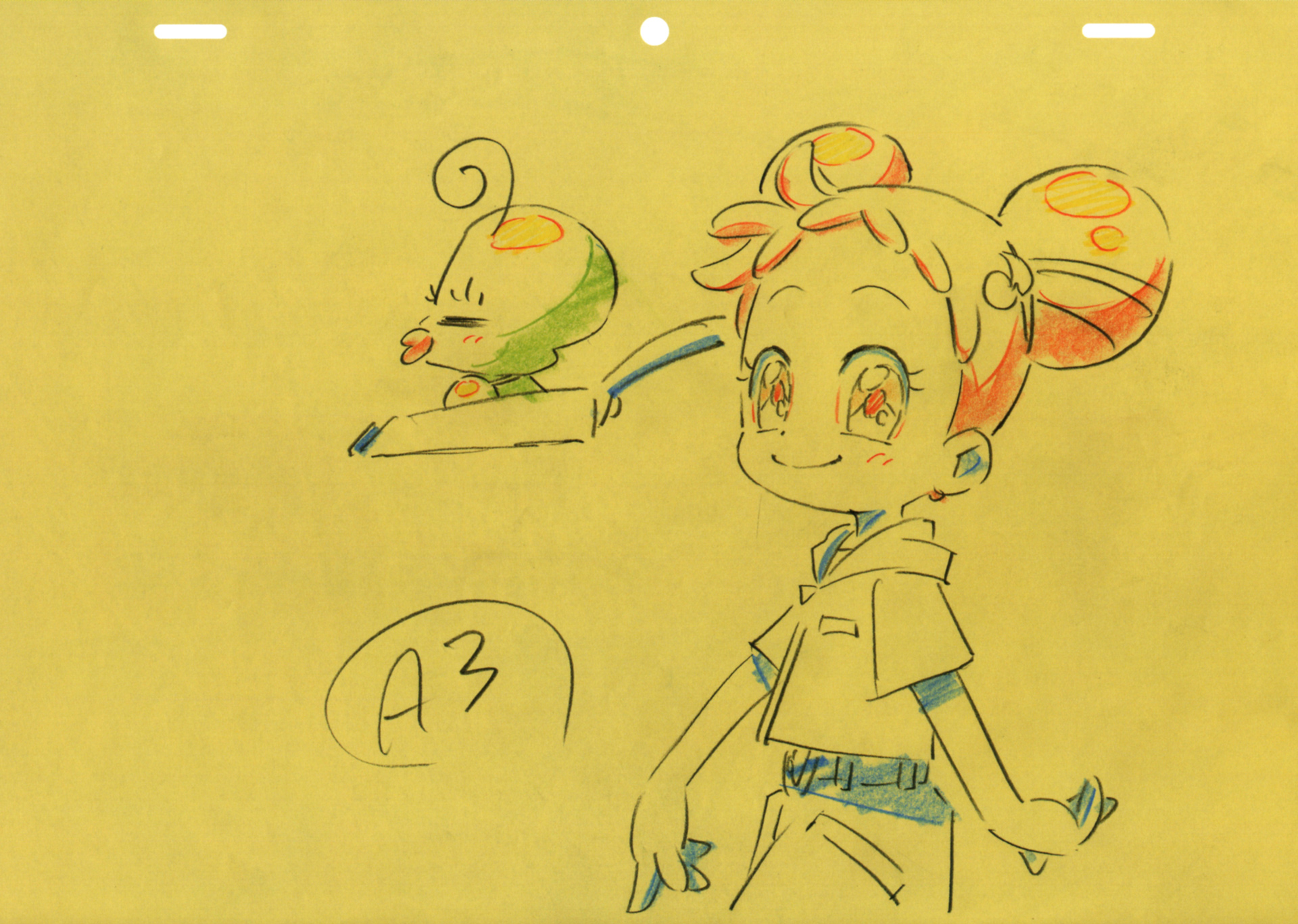

Together they made sure not just to foster that youthful creative energy, but to channel it in ways that would truly affect the audience. Their influence led to aesthetic decisions like further stylizing the finished designs to encourage kids to draw them, as well as smart structural ones; having had lots of time to think about the best approach for a project aimed at kids, SatoJun and the writing team conceptualized a world at the scale children perceive, with the school as a central hub and very involved side characters who grow alongside the main cast.

If that sounds like a formidable team with very clear ideas, wait until you hear about the consistent appearances of guests who need no introduction, from Sushio to Mamoru Hosoda. However, that’s not all there is to the show’s success. If amassing talent was all that commercial animation needed to succeed, projects like Ojamajo Doremi would be more commonplace, and wars would probably be over as a consequence—unfortunately, neither is the case. For teams like this to live up to their best potential, producers need to be able to provide them the right canvas, as well as minimize interferences by actors who are only involved to make money from the project.

Fortunately, Toei producer Hiromi Seki has always been on the same page as Ojamajo Doremi’s creative team. While the context already benefited them somewhat—SatoJun has cited the success of his previous project Yume no Crayon Oukoku as key for the leeway they got—Seki was instrumental to the process regardless. Securing an original project, making sure that the seasonal merchandising demands where unobtrusive, allowing them to get away with no weekly formula and non-plot related resource allocation to maximize the creative freedom, actively seeking new brilliant creators as the franchise has evolved, so much of Ojamajo Doremi’s success traces back to her actions. As it turns out, not all producers are greedy lizard people! Only the vast majority of them.

Given this once in a generation mix of talent and freedom, it’s no surprise that Ojamajo Doremi accomplished all of its goals. And that begs the question: what were those objectives? The intent to become a constant source of joy is a given, and some themes you could infer from the premise alone; as a story following a group of kids who quite literally stumble upon becoming witch apprentices, you can bet there’s a recurring message of avoiding easy half-hearted solutions—magic—to problems best approached with emotional sincerity. In the grand scheme of things, though, the biggest challenge that they decided to face was derived from that mindfulness of their audience that we keep coming back to. The show used its school setting as a microcosm of the world that children experience, filling it up with dozens upon dozens of personal stories that introduced the target audience to important issues. The result was deeply relatable, not by presenting a toothless compilation of average lives, but by collecting the collection of outliers that actually make up a community, even if that meant having to deal with many thorny subjects.

Ever since the start, Ojamajo Doremi followed the unique stories that spurn off certain family structures, social standings, and even racial origins. It also refused to shy away from issues everyone will eventually have to face regardless of their personal circumstances, such as mortality and societal expectations. And it did so without sugar-coating those issues, treating its young viewers with respect and trusting them to be able to handle any topic as long as it was presented properly.

The kids at home might not have been able to grasp the full implications of every thorny issue. By design, it was impossible for all of them to hit home in the first place. But some episodes would surely make them think about something they’d experienced, be it in their own lives or a friend’s, and chances are that no piece of media had taken its time to properly talk to them about it before. Even if that didn’t happen immediately, Ojamajo Doremi’s iconic delivery would likely stick with them for long enough to actually encounter one of the situations covered in the show. That’s what made it such a formative experience for kids, as well as something very easy to appreciate as an adult—whether you were a parent at the time, someone revisiting it later, or an entirely new fan getting to it now.

While writing this piece, I approached several friends who like Ojamajo Doremi about as much—meaning a whole lot—despite having experienced the series at different points in their lives. I asked them if there were any particular instances of Ojamajo Doremi tackling an adult, complex, or otherwise nuanced topic that had stuck with them more than anything else. Everyone coincided that the general approach to the storytelling deserved a lot of credit in the first place; that lack of a predetermined weekly formula, the willingness to introduce subplots and then allow them to mature naturally in the background, are big reasons why the climactic resolutions felt so earned.

For a precise example, you simply have to look back at Nagato’s character arc across the entire third season. She was formally introduced before the halfway point as a recluse not attending school for undisclosed reasons, and following its own text, the show refused to take a quick magical shortcut to solve a real problem. Sure, Doremi’s bright character allowed her to immediately befriend Nagato… but her attempt to come back to school was met with failure and truly asphyxiating direction courtesy of SatoJun and Igarashi themselves. Nagato’s return was gradual—first getting a desk at the nurse’s office, then rejoining the class near the end of the season—and it took the whole community to face the problem at the root of her trauma: the tendency to trample over kids seen as slow learners by traditional metrics, despite Nagato having proved to be brilliant. This restraint strengthened Ojamajo Doremi beyond the already large sum of time it spent on each important topic. Especially to the active imagination of a child, it was easy to perceive situations like Nagato’s as organic, with each impactful reappearance across a whole season further convincing you that those characters had real lives that extended beyond their screentime.

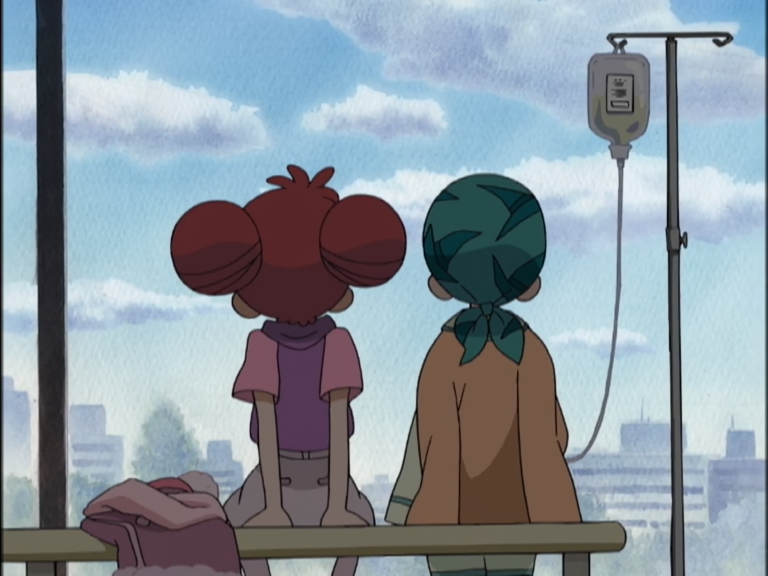

Unsurprisingly, there was quite a lot of overlap in the responses I got asking for highlights like that. After all, there were obvious standout episodes simply from a conceptual standpoint. Examples like Motto! Ojamajo Doremi #14, which attacked racism—manifesting through painfully realistic bias—and did so head-on, foregoing any type of allegory. Death was also approached from multiple angles, though always with no subterfuges. Sometimes it was a more distant death like Igarashi and Umakoshi’s first major collaboration in Ojamajo Doremi #30, with acceptance as the theme, while others dealt with the direct, blunt impact of mortality; Ojamajo Doremi Naisho #12 had the titular character befriend a terminal leukemia patient who happened to be very fond of witches, forcing her to experience bitter loss first hand. From arcs that took main characters to find out that their parents’ divorce was a complex problem involving tragedies no one could be blamed for such as a miscarriage, to small moments like Doremi herself learning that her mother entertained suicide until she became a new source of hope as her daughter—there were many turns so daring that they immediately come to mind.

At the same time, though, the answers I found most interesting were the more subdued episodes that left just as strong of an impression on certain people. Attributing Ojamajo Doremi’s to the taboos it tackled actually does the show a disservice, as the delivery felt just as thoughtful when they approached less extreme themes. This was demonstrated in cases like Motto! Ojamajo Doremi #10, a candid episode about puberty built around a female classmate whose insecurities about being taller than the norm we’d already seen before; not a life-or-death situation like some of the examples we’ve gone over, but still an underrepresented topic that was dealt with equal grace. The same applies to episode #15 barely a month later, which was chosen as a highlight by a different acquaintance of mine. Its focus was instead on societal expectations, as a classmate who otherwise loved his single mother felt conflicted about her running a bar at night as that is not seen as a normal thing for women to do. Even more representation of different family structures, as well as an excellent example of side characters with similar experiences intervening in their classmates’ growth after having bettered themselves. And, on top of that, the charismatic direction and storyboarding we’ve come to expect from Igarashi himself.

That brings us to an entirely unsurprising topic that is worth noting regardless. As much credit as the writing team captained by Takashi Yamada deserves for that breath of unique topics, it was only when their ideas and the series directors’ input overlapped with exceptional storyboarders and episode directors that the show truly lived up to its potential. Fortunately, that was a more common occurrence than in pretty much any other long-running series. The core staff members themselves were behind many of such episodes, especially those who occupied the series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario. seat at some point.

Armed with his understanding of Onpu’s character and an unmatched ability to project introspection outwards, Yamauchi made Ojamajo Doremi Naisho #04 into an unforgettable experience. One that kids might not have been capable of immediately relating to, as existential dread born from lost professional passion isn’t exactly what keeps children awake at night, but also one so memorable it might have stuck with them for long enough for the theme to become relevant to their lives; and I say might knowing it has, as I’ve been told by people who only truly appreciate the episode now. The fulfillment Onpu once got out of a job that was akin to a dream had withered, just like the flowers that served as the storyboard’s motif. After pondering who Onpu Segawa even was, the fallen petals led her to a tree she’d once visited as a child—helping her realize growth is cyclical, that gradual change occurs even as we don’t notice it, and that all she needed to do to regain her motivation is attempt new challenges that were only available to her in the present.

Were there outlier guest directors behind some of the most fully realized episodes too? The answer is yes, though with the caveat that those tended to be more self-contained moments, usually smaller in scope. However, that happens to be no issue when your name is Mamoru Hosoda and you’re coming back to your old studio after a traumatic experience at Ghibli. Hosoda didn’t hide that those bitter memories fueled Ojamajo Doremi Dokkan #40, but even if he’d never spoken about it, the episode’s themes alone spell it out. Feeling down over her impression that all her friends were more talented and had already found a goal, Doremi gravitated towards Mirai, a mysterious witch who’d opted not to use her powers to instead create manually. Should Doremi discard everything and follow her, or remain where she’d always been to wrestle with that feeling of inadequacy? The episode delved into the relativity of time—embodied by glass, solid to the eye of humans but in a constant flow to witches who live much longer—and synthesized the kind of painful decisions you have to take as an adult into one of the most iconic metaphors in anime history: the literal crossroads of life that all fans of The Girl Who Leapt Through Time will recognize.

During the preview at the start of that episode, Doremi pondered to herself if she’d ever be able to understand the words Mirai told her. Given the franchise’s history, words like that didn’t come across as patronizing, but rather as further proof that the staff really did have faith in their mostly young audience. This was a team that built a whole world to their scale, tried to make it relatable by including very diverse life experiences, then explored all sorts of topics that kids could benefit from hearing about. And, every now and then, they’d cover a topic clearly out of the scope of a child’s mind… but with a delivery so evocative that the audience would be likely to look back on it later in life; and, while they were at it, it’d give food for thought to the parents watching the show alongside their kids. The existence of a fanbase that still holds the series tremendously dearly, despite Ojamajo Doremi not having been as everpresent as some of its peers, proves that the team’s faith paid off.

That alone would make the series one of the greatest, frankly most important anime out there. An incredibly daring kids show that’s even more impressive in retrospect, one that’s a joy to rewatch if you first experienced it as a child but easy to get into if you never had that opportunity. But Ojamajo Doremi’s tale doesn’t end there. Because, as it turns out, that same thoughtfulness regarding its audience made the franchise evolve in unique ways.

As everyone who doesn’t live secluded in a cave has likely noticed, we’re currently in an era of remakes, reboots, reimaginings, revivals, and any word that starts with re and can be mostly attributed to cynical producers profiting off demographics that now have a bit of spending money. When it comes to anime, nowhere is that more apparent than at Toei Animation; something that makes sense when you consider that they operate more like a regular corporation than any other studio, and that they do have many massive IPs at their disposal.

With that in mind, an Ojamajo Doremi follow-up sounds like something that would be approved in a heartbeat. If only that was the case, is what Seki would respond to that. The truth is that it’s taken the actual team behind the show pestering higher-ups for years, and they only barely managed to get the OK for something sizable coinciding with the 20th anniversary; a deal so flimsy that they had to keep quiet and vaguely allude to it even as they’d already received a preliminary go-ahead. While very popular at the time, Ojamajo Doremi never became an eternal money-printing machine like some of its more fortunate peers; and, to be fair, how could it when the show itself kept discarding its gimmick toys and refused to make a big deal out of them? Given that it’s not an easy sell by any stretch, an Ojamajo Doremi return could only come from its creators putting on pressure towards a clear goal. So now is the time to ask: what were those ambitions that led to the 2020 film Looking for Witch Apprentices?

After considering multiple approaches, they ultimately settled on a rather unusual approach by placing the popular original characters somewhat in the background to explicitly focus the narrative on the generation of young adults who’d grown up with Ojamajo Doremi; yet another showcase that marketability has never been a big concern for the team. While this might sound outrageous, it’s so perfectly in line with the franchise’s philosophy that it’s impossible to imagine any other outcome in retrospect. Even the discarded pitches for the film involved a grown-up cast, and while its reception was always been much more mixed, the only noteworthy Ojamajo Doremi releases ever since the Naisho OVAs were the Doremi 1X novels, which already followed the characters into adolescence and young adulthood. As a show that always carefully considered its relationship with the audience, growing up alongside them feels like the most thematically appropriate route.

And it’s not just the narrative that has taken this path, the same applies to the team behind this new movie too. Considering how deeply in love with the series the original team was, it’s unsurprising to see pretty much all of them rushed to come back for this. That includes Igarashi, who had not set foot into Toei for 14 years yet made an effort to contribute to the storyboarding process, as well as Nagamine, who’s currently so busy with One Piece he couldn’t do the same but still forced his way in to direct a lovely tie-in commercial. Even the list of animators is chockfull of returning faces, from Sushio to Umakoshi himself. A veteran team like that led by SatoJun would have more than enough to put together a satisfying movie.

Would that have been the most Ojamajo Doremi thing to do, though? Neither Seki nor the rest of the core staff thought so. Instead, they went out of their way to give a central role to up-and-coming staff, much like the original series had done back in the day. Given the theme of the film, they researched what preoccupies kids nowadays and what life is like for the young adults who grew up with the original anime. In the end, Seki specifically sought a young woman to co-direct the film precisely because that felt like the natural fit for a movie focusing on people from her generation, eventually settling on Haruka Kamatani—a creator with tremendous potential we’ve written about multiple times. The fact that she had never seen Ojamajo Doremi prior to this pitch and yet was chosen for the job speaks highly not just of Kamatani’s skills, but of the genuine commitment this team has to their ideals. As first time director and lead storyboarder, she captained a team featuring many other young Toei stars, as well as equally interesting outsiders like Shouko Nakamura. And given the critical reception, it seems like surrounding youngsters with capable veterans has once again led to success.

A certain key animator in the new movie shared a cute anecdote. A friend she’d known since kindergarten and bonded with thanks to Ojamajo Doremi, having fun together emulating the adventures of the witch apprentices, had just contacted her. With no knowledge of its production, she’d gone to the theater to watch Looking for Witch Apprentices, where she just happened to catch her old friend’s name in the list of animators. And that about sums up what Ojamajo Doremi is—then, and still now. A precious, important memory for a whole generation, but one that’s kept accompanying them rather than let itself stagnate in the past.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

I really want to jump into the series after reading through this and seeing some stuff you posted on Twitter. It’s crazy how hard its been to find any means of watching or buying online in the US, hopefully there’s a chance it comes to streaming soon. I can imagine the dub wasn’t handled very well here, 4kids was pretty notorious for its localizations at the time. I’m curious, I saw you said you were rewatching the series, did you rewatch the sub or Spanish dubbed if that is the version you originally saw? I’d be interested in watching the… Read more »

It’s the Catalan dub I watched over and over as a kid, but I’ve got plenty of friends who watched the Spanish version instead and they loved it as well, so I doubt they mangled the localization at some fundamental level. Actual dub quality I can’t speak for, though!

But yeah, it’s a bit of a tragedy that there’s no proper release for English speakers…

Nice to know, thanks for responding and it would be cool to read more of these breakdowns of older series or movies in the future.

I started watching it in some local channel here in Spain, but after some episodes I just couldn’t follow it anymore due to my studies.

I liked it just fine, but I couldn’t imagine it had such an impact, so I am seriously considering giving it a change if I have time to do so.

I couldn’t agree more, for all the difficult topics the series handled so well, what makes it a joy to watch (and rewatch) is how fun it is at its core. Letting kids ride a bus to other cities to promote their own shop? Letting them raise a kid and explore what it means to be an adult? But also having entire episodes about a dog becoming a witch apprentice, two dumb kidnappers and an over the top old housemaid. There’s a strong sense of freedom, like the show itself tells you that even if you are kid, there’s so… Read more »