Isao Takahata: A Complete Retrospective

Grave of the Fireflies was released 30 years ago on April 16, 1988, alongside its equally renowned sibling movie My Neighbor Totoro. Most unfortunately, its visionary director Isao Takahata passed away at the age of 82 just a couple of weeks ago. Today we’re here to honor not just his most famous film, but a whole career filled with revolutionary, sometimes underappreciated work. This is how Takahata changed anime and his own self.

Isao Takahata ventured into the world of anime in 1959, joining Toei Douga in the midst of labor disputes after studying French literature at the University of Tokyo. European and particularly francophone culture always fascinated him, something that had a clear effect on his work as he introduced aspects of French New Wave to it, as well as taking not just aesthetic but moral inspiration from his idol Frédéric Back. But it was Paul Grimault and Jacques Prévert’s The Shepherdess and the Chimney Sweep – an unfinished version of The King and the Mockingbird – that made him curious enough about animation to give it a try. Once at the studio, he was quickly taken under the wing of legendary animator Yasuo Otsuka despite not having drawing skills himself. Takahata would eventually gain the firmest grasp on animation this industry has seen from someone without a background in the subject, and he wasted no opportunity to thank Otsuka for his continued mentorship during his first years in the anime world.

Much like Otsuka quickly scouted him, Takahata immediately picked up on the extraordinary talent of a young animator who joined 4 years after he did: none other than Hayao Miyazaki. His interest in the person who would eventually become his best friend, rival of sorts, and the most popular anime creator of all time was beyond professional; he pushed him towards the union to exploit his charisma, and saw in him the perfect compliment he needed. Because of Takahata’s inherent limitations when it came to making anime, he always had to make sure he had a second-in-command capable of turning his ideas into animation, and Miyazaki flawlessly fulfilled that role for years. Though by the end of 1963 Takahata already had gotten promoted to handle some episodes of Wolf Boy Ken, Toei Douga’s first TV anime, their first major collaboration had to wait until 1968, when Isao Takahata’s majestic directorial debut Horus Prince of the Sun was finally released. It was his mentor Otsuka, entrusted with animation directionAnimation Direction (作画監督, sakuga kantoku): The artists supervising the quality and consistency of the animation itself. They might correct cuts that deviate from the designs too much if they see it fit, but their job is mostly to ensure the motion is up to par while not looking too rough. Plenty of specialized Animation Direction roles exist – mecha, effects, creatures, all focused in one particular recurring element. on the film, who insisted no one else could direct it. Had he backed down, the history of anime might have been very different.

Against his own nature, Takahata had to make compromises for to his first movie, a nonetheless titanic production beyond its time. The Ainu elements from the original story were forcefully removed and replaced by a Scandinavian setting deemed more appropriate for the masses, which makes its first US title The Little Norse Prince feel like a bitter betrayal. Beyond that, his original ideas had to be trimmed so much that the end result is densely packed to the point of being frankly exhausting; an unceasing stream of intense developments with no room for levity and relaxation doomed the movie when it came to an audience that, as the director himself acknowledged, wasn’t ready for an animated piece with no humor whatsoever. And while I do agree that Horus is kind of a draining experience, I also believe it stands on its own as a film, besides its undeniable relevance as an industry milestone.

In the end not everything that Takahata conceptualized could be realized, but when it comes to what did make it into the film, no corners were cut. Narratively barebones as it may be, Horus is an inspiring celebration of the power of community that reflects the times and the collaborative environment in which it was made, filled with interesting visual concepts and Takahata’s incipient desire to immerse the viewer in a culture and its customs. Although Horus is technically its protagonist, the emotional core is by all means Hilda, a textured female character who felt so revolutionary at the time that even Miyazaki admitted that virtually no one within the team understood Takahata’s vision. According to him, only the director and Yasuji Mori, who was in charge of bringing her to life, truly grasped the nuance of her tragic character. But rather than wielding that as criticism, Miyazaki argued that it made everyone else’s work pale in comparison to Mori’s affecting animation, being particularly impressed by the scene where she shows willingness to sacrifice herself. The range of expressions she shows at the end, mixing both resignation and resolve, was poignant in a way Horus’ peers couldn’t aspire to be, and remains impressive to this date.

Though it’s fair to consider Mori’s depictions of Hilda to be the most emotionally charged sequences in the film, the rest of the team didn’t lag behind in terms of technical prowess. If one were to watch the movie unaware of its context, only the two scenes that remained unfinished (the wolves’ attack and some cuts as mice raid the wedding) would hint at a troubled production, as Horus was otherwise an almost unparalleled showcase of animation in the fledgling Japanese animation industry. The fight against the fish was one of the most authentic scenes that Yasuo Otsuka ever animated, the carefully depicted traditions served as the perfect teaser of what Takahata would eventually achieve, but perhaps most impressive was the sheer volume of outstanding cuts contained in the film. Horus was the result of a group of passionate creators arduously bruteforcing something that shouldn’t be able to exist, the peak of Toei Douga’s theatrical golden age – in the sense that it was their pinnacle, but also the start of a decline. They would still put together some very impressive titles, like the Puss ‘n Boots movies that Toei owe their logo to, but none quite reached the same brilliance as Horus, as the gradual break-up of that team in the years that followed marked the end of an era.

At a time where anime was still trying to figure out its identity, Horus’ performance became an important factor. Takahata’s revolutionary ideas illuminated the way for other creators, while its commercial flop and production troubles confined projects like this to their own niche, letting a more conservative approach to anime manufacturing become the norm we see today. After someone passes away there’s an understandable desire to acclaim their every action as a success, especially with an exceptional person like Takahata, but I believe it’s important to understand that even his shortcomings and missteps would come to reshape anime. Toei Douga’s executives played a role in the shadows here, delighted to sacrifice a figure like him so involved in union disputes, but Takahata’s own inability to readjust his vision according to production realities haunted him in the form of scheduling nightmares throughout his career, with almost all of his movies having suffered delays. Let’s not forget that Paku-san, the affectionate nickname his Ghibli colleagues would come to refer him as, was derived from the fact that he would constantly rush late into the studio still munching on his breakfast – thus a パクパク sound. Lateness was very much part of his identity.

Taking the full blame for Horus’ partly manufactured failures, Takahata was demoted and sent to more modest TV projects like Moretsu Atarou, but his days at Toei Douga were numbered. By 1971 he’d left to join A Production alongside Miyazaki and Yuichi Kotabe, for the chance to once again work with their mentor Yasuo Otsuka (who had shown them new possibilities for serialized animation with Moomin) but also with the explicit intention to make a Pippi Longstocking anime. In the meantime they took over the production of Lupin III during the 2nd half of the original series, essentially rescuing one of the most iconic franchises from a potential premature death due to poor ratings. Not everything worked out well however, and despite all the pre-production work and Miyazaki’s multiple trips to Sweden for location scouting and to talk with the author, they were never able to secure the rights and had to scrap the plans… sort of, since many of their ideas for Pippi Longstocking were repurposed into their later works, most notably in Panda Kopanda and its sequel. Besides their origins and delightful A Pro-esque animation excerpts, these two short films mark a turn for the quotidian, which would be Takahata’s focus henceforth. He joined the industry with more fantastical goals, since in theory those embody the possibilities of animation much better, but he quickly realized daily events were the vehicle he should use to meticulously portray life.

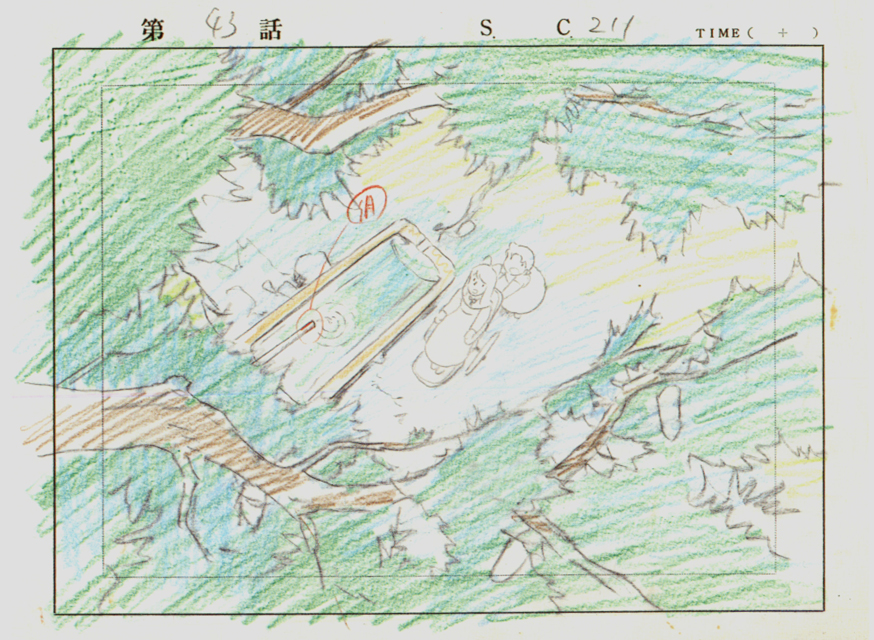

The results of that shift in mentality could be felt in Takahata’s contributions to Fuji TV’s World Masterpiece Theater block: Heidi Girl of the Alps, Marco 3000 Leagues in Search for Mother, and Anne of Green Gables, produced at Zuiyo Eizo and then its successor Nippon Animation. What Takahata and his team achieved there is such an astonishing feat that no summary could do it justice, but at the very least I should highlight that they changed anime production forever with the introduction of the layout system. Up until that point, the norm was to go from the storyboards to key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style., but Heidi introduced an extra step that would go onto become an anime staple: a set of blueprints referred to as layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists., which expanded the ideas of the storyboardStoryboard (絵コンテ, ekonte): The blueprints of animation. A series of usually simple drawings serving as anime's visual script, drawn on special sheets with fields for the animation cut number, notes for the staff and the matching lines of dialogue. into an animation sheet. The number of retakes plummeted while the quality in general skyrocketed, so the experiment paid off and with time that became the way all anime is manufactured. Now that doesn’t mean that their exact model was copied though, since the way those productions operated responded to the idiosyncrasies of that team; Takahata is a director who doesn’t draw yet has very precise visual ideas, so he needed a capable second in command, which of course turned out to be Miyazaki drawing every single layout in those shows. Had it been a director with a background in animation, or a team without a monster like young Miyazaki at their disposal, the arrangement would have been very different. History was made because the stars happened to align in that exact way.

Besides this innovative, exceptional production and writing that felt more refined than their contemporaries, these WMT series stood out because of how physically grounded they were in their settings. Takahata’s thoroughness was becoming a staple at that point, so he went on extensive research trips alongside his companions to find something that photos alone couldn’t convey. A competent visual backdrop wasn’t enough. Takahata wanted to believably capture societies, forcing Miyazaki to draw many sketches of what the insides of people’s homes might have been at the time, constantly reading up on customs himself. When he revisited Anne’s setting many years later, he still oozed with knowledge about the ways of life of Prince Edward Island’s inhabitants at the time, allowing him to recall some fun anecdotes as well. Takahata’s next major work Chie the Brat came from the same mold as Panda Kopanda, but as a tale tangibly set in the booming 60s Osaka, it felt like a clear evolution. Coupled with its wide range of expressiveness, festive spirit, and understated yet touching familial tale, Chie was one of the best encapsulations of pre-Ghibli Takahata; it doesn’t necessarily bring new aspects to the table, but with Telecom’s robust team at his disposal the execution is well-worth the price of admission.

Next came Gauche the Cellist, a fascinating experiment that stands out within Takahata’s oeuvre by feeling ahead of its time; though as a director he constantly trod new ground, his progression always felt very orderly, step-by-step, in a way symbolizing Takahata’s logical nature. Gauche on the other hand was a sensorial experience that resembled his final film the most, with a spectacular diegetic intro that tied the two pillars of the film together: music and nature. A musician who feels off-key with his peers becomes more empathetic through various meetings with talking animals, constantly interweaving sound and action in a masterful way. Gauche was the labor of love of a small crew: there’s Takehata as the single directorial figure and adapting the script of course, but also Michio Mamiya who lent it the music at the core of the film, art directorArt Director (美術監督, bijutsu kantoku): The person in charge of the background art for the series. They draw many artboards that once approved by the series director serve as reference for the backgrounds throughout the series. Coordination within the art department is a must – setting and color designers must work together to craft a coherent world. Takamura Mukuo providing most backgrounds, and of course Toshitsugu Saida as the character designer and solo key animator. It may not be the most technically impressive Takahata movie, but there’s a harmonious cohesion to it born from the fact that it was such a personal project, and it’s hard to believe any external collaborator could have grasped the soul of the movie as well as Saida did. His virtuous 1 hour long solo key animation effort, produced over a long period of time, stands as another milestone in anime.

Having arrived at this point, talking about Isao Takahata inevitably means tackling legendary studio Ghibli, as their stories become so intertwined that it’s impossible to separate them. Because of that, it’s necessary to backtrack a few years to meet the third pillar of the studio: Toshio Suzuki, at the time an employee of Tokuma Shoten. In 1979 he got transferred to the anime magazine they planned on launching – Animage, still one of the major monthly publications in the field. Suzuki specialized in reporting criminal cases and didn’t really know anything about animation, which led to him reaching out to many people for help. One of his first tasks was covering classic titles for a column in the magazine, for which he chose Horus. As detailed in The Birth of Studio Ghibli, Takahata’s amusingly long response after being contacted by him simply came down to “I can’t give you a response,” but he hooked him up with Hayao Miyazaki, who talked with Suzuki for the first time and established perhaps the most important bond in the history of anime. Unfortunately for the young Suzuki though, that didn’t help him much for his article either. Never trust eccentric creators to reveal their secrets.

Suzuki met Miyazaki for the first time when covering Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro and fell in love with his work. Though he kept on getting ignored at first, Suzuki used his editorial position to push for more Miyazaki features, which eventually led to them developing a friendly relationship. Their discussions allowed Suzuki to realize that Miyazaki was bursting with original concepts, so he attempted to get one of them made into a film… but was met with immediate refusal, as investors saw no hope in an animated property not tied to an existing comic. Suzuki turned that into his own weapon and convinced Miyazaki to draw the Nausicaä manga, first published in his Animage magazine in 1982. The positive reception in comic form allowed the film to be greenlit at last. Takahata’s position as its producer tends to be treated as a minor curiosity, but it’s been noted many times that it was him who discovered composer Joe Hisaishi and made him a core element of Ghibli’s identity, while also mentoring Suzuki before he became one of the greatest producers in the industry. Once again, Takahata was a quiet detonator of greatness.

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind was met with exceptional critical reception and widespread popularity, but the road leading to that was so taxing in many ways that the team felt they needed a change of pace. For starters, Takahata went on a location hunting trip to Yanagawa, a city in Fukuoka renowned for its wide net of canals, as they’d identified that as a potential setting for another project. The most remarkable development however related to the where, rather than what they would make; Topcraft, the company where they had produced Nausicaä, was on its way out, and so the main figures behind the movie decided to create a company of their own: the one and only Studio Ghibli, which came to existence as a subsidiary of Tokuma Shoten due to Suzuki’s involvement with the whole ordeal.

Though Takahata was of course also one of the co-founders, at the time he was rather literally immersed in his own project. He had fallen in love with Yanagawa and the community that symbiotically existed within its myriad of canals, so what was intended to be an animated feature ended up becoming a live action documentary. Miyazaki, riding off the success of his previous film, personally lent him funding… and came to regret that, since Takahata’s usual delays and over-spending were about to put his friend in trouble. As Suzuki himself has admitted, the main drive behind Laputa: Castle in the Sky (1986) was to make some money before things turned sour, making this yet another case of one of Takahata’s shortcomings being integral to the history of anime.

In 1987, after two years of filming and a long editing process, The Story of Yanagawa’s Canals was finally released. The documentary isn’t as easy of a recommendation as his animated pieces, not so much for a lack of quality but due to its nature: close to three hours of the history of Yanagawa and its people, extended sociology detailing the relationship of Japanese people with water, as well as the plan to salvage the canals once they had deteriorated, all told with the excruciating detail that characterized Takahata. By all means do check it out a few chunks at a time if you’re curious though, since the more you watch the more you realize why this became his passion project; from the nature-man relationship to the success of the community, it had all the right ingredients. By the time he managed to wrap up Yanagawa’s Canals though, Suzuki had already begun pitching concepts for new Ghibli projects. In spite of Miyazaki’s previous successes however, the proposal he presented was initially rejected, as investors again failed to see the hook in the adventures of children and some cute creatures in a post-war setting – something that in retrospect might be the funniest Ghibli anecdote, considering Totoro’s timeless popularity. Suzuki counterattacked by making it a double feature, also including a film based off Akiyuki Nosaka’s short semi-autobiographical war tale that would be directed by Takahata. A risky bet that proved to have a nightmarish effect on the company, as juggling two demanding productions was nearly impossible, but that led to big successes nonetheless.

And so 30 years ago, on April 16, 1988, the world of animation saw a 1-2 punch like no other with the double release of My Neighbor Totoro and Grave of the Fireflies. Two epoch-making titles in their own right that could have only been brought to life by their respective directors. Suzuki suggests a fundamental dichotomy in film-making to illustrate the difference between the two main directors at Ghibli; while both Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata initially draw from their surroundings to create something, the former’s goal is to spark people’s imagination through something they’ve never seen before, while the latter presents familiar events to give us new insight in the way we live. Those contrasting mentalities are gracefully exemplified by Miyazaki’s tendency to set his stories high up, making the viewer fly about using the planes he loves or through some magical means, whereas Takahata is firmly grounded on the floor.

When it comes to Grave of the Fireflies, the tale wasn’t only physically rooted in the soil but also in Takahata’s own memories, which he didn’t hesitate to turn back to as a way to increase the authenticity of such harrowing events. It’s not through exaggeration that he made it such a powerful piece, but rather by meticulously depicting life as it was at the time in the way only he could do it. The gradual degradation of their utensils and the liveliness vanishing from the kids’ demeanor were just as heartbreaking as the explicit narrative developments, showing the brutal impact his approach could have given material this heavy. Takahata’s unwavering hand even when filming a movie like Grave of the Fireflies increased his reputation as a bit of a cold figure, but personally it’s always come across as strong determination instead. It’s true that there’s kind of a poetic detachment from his early output, a dispassionate delivery perhaps, but after this movie in particular he began pouring increasingly more of his own self into his work. I don’t know if this production was a healing experience for Takahata, unlike what the original author had to go through. What I do believe however is that it was a movie he had to make, and that there’s a sense of relief in his subsequent pieces. I wish I still had a chance to ask him, among many other things, if it played a role to allow him to move on.

It’s no exaggeration to say that with Grave of the Fireflies, Takahata opened up a door to a new brand of methodical realism that didn’t exist in anime until that point, if not in the world of animation altogether. While his work was always grounded in reality to a degree, he’d been wary of the awkwardness lying beyond a certain threshold for a long time, so perfecting this approach was an arduous process. Way back in 1959, a certain scene in Shounen Sarutobi Sasuke – which he was an assistant for – was met with laughter rather than the intended dread, since its key animator Yasuo Otsuka depicted a skeleton fleeing with such verisimilitude that the audience parsed it all as comical. The answer Otsuka arrived to was that his goal should be constructed realism rather than genuine realism, to evoke the feeling of life rather than to try and imitate it. That was a formative experience for Takahata as well, but since his mentor was a pure animator unlike him, he had to approach this issue from a different angle. His solution was instead to sprinkle the real life he meticulously portrayed with some magic: not just the explicit fantastical elements present in many of his movies, but also aspects like the magical role the fireflies play in this movie – these non-narrative fantastical moments would only increase from this point onwards. This strategy to balance things out may seem at odds with Takahata’s logical core, but I find these magical sequences to be his almost mathematical solution to a very human problem, which embodies his identity as director.

While I’ve been focusing on Takahata, it’s unreasonable to isolate him from the teams that crafted his works. Ghibli’s projects were very personality-driven, with the director conceptualizing every single element, but Takahata’s mandatory reliance on animators and his belief in anime production as a communal effort set him apart from a one-man army prodigy like Miyazaki. Directors who can’t draw aren’t all that unusual, and Takahata had a fantastic sense for composition despite his lack of skills, but a high-profile director like him maintaining certain visual concepts for decades even as he worked with different teams speaks volumes of the clarity of his vision. Takahata had exceptional scouting abilities and always managed to convey exactly what he wanted, despite not having the technical capabilities nor the visual background of his peers. He surrounded himself with brilliant creators, having the late Yoshifumi Kondo provide Grave of the Fireflies’ character designs and supervising their understated solidity, while the unparalleled inventiveness of Yoshiyuki Momose turned him into his right hand man from that point onwards; Momose didn’t just become his storyboarder of choice, the visual concepts from his imageboards convinced the director so much that they tended to make it to the film almost untouched. There’s no denying that combining the talent and ambition of artists like them with Takahata’s groundbreaking realistic approach made it a demanding production (despite very similar lengths, Grave of the Fireflies required 54,660 drawings versus Totoro’s 48,743), but the result made it all worth it. There’s a clinical precision to its acting that has hardly ever been matched outside of Takahata’s following works. The production was a formative experience for its animation team, giving the first true taste of thorough, restrained realism to the likes of Yoshiji Kigami, while some iconic sequences started showcasing true momentum and volume, matching anime’s trend towards photographic realism that scholars like Yuichiro Oguro have documented. Its popularity then enabled new means of expression for creators who weren’t even involved in its production, as Takahata had proven this was a valid new canvas for animation. Grave of the Fireflies was a massive success even beyond the goals it had set for itself.

It only took a year for Ghibli to put out their next hit. Kiki’s Delivery Service captured the hearts of many young girls, with Takahata assisting Miyazaki from the sidelines once more as music director. However, its production raised a very serious dilemma – despite Kiki being granted twice the production budget as previous films, the staff ended up making way too little money considering the amount of effort that they had put into it. The scope of the whole endeavor, the number of retakes needed when working with a perfectionist like Miyazaki, an outrageously high number of drawings, and the fact that it mostly relied on freelancers contracted on a per-project basis (the prevalent way of operating in the industry nowadays still), made the idea of working on a Ghibli film not all that enticing. And that was a big problem for Miyazaki and Takahata, who’d been very involved in the defense of worker rights in their youth and founded Ghibli with the explicit precept that artists should only stay under their roof as long as they felt comfortable there. The only two options they considered were to either close down, or to bet everything they had on fully reforming the way the studio operated. In a showcase of principles that’s rare in the anime industry, they chose the latter. Ghibli would from now on offer full-time contracts to their staff and dedicate themselves to training youngsters, growing their own animation culture and lessening a huge amount the need to rely on outsiders.

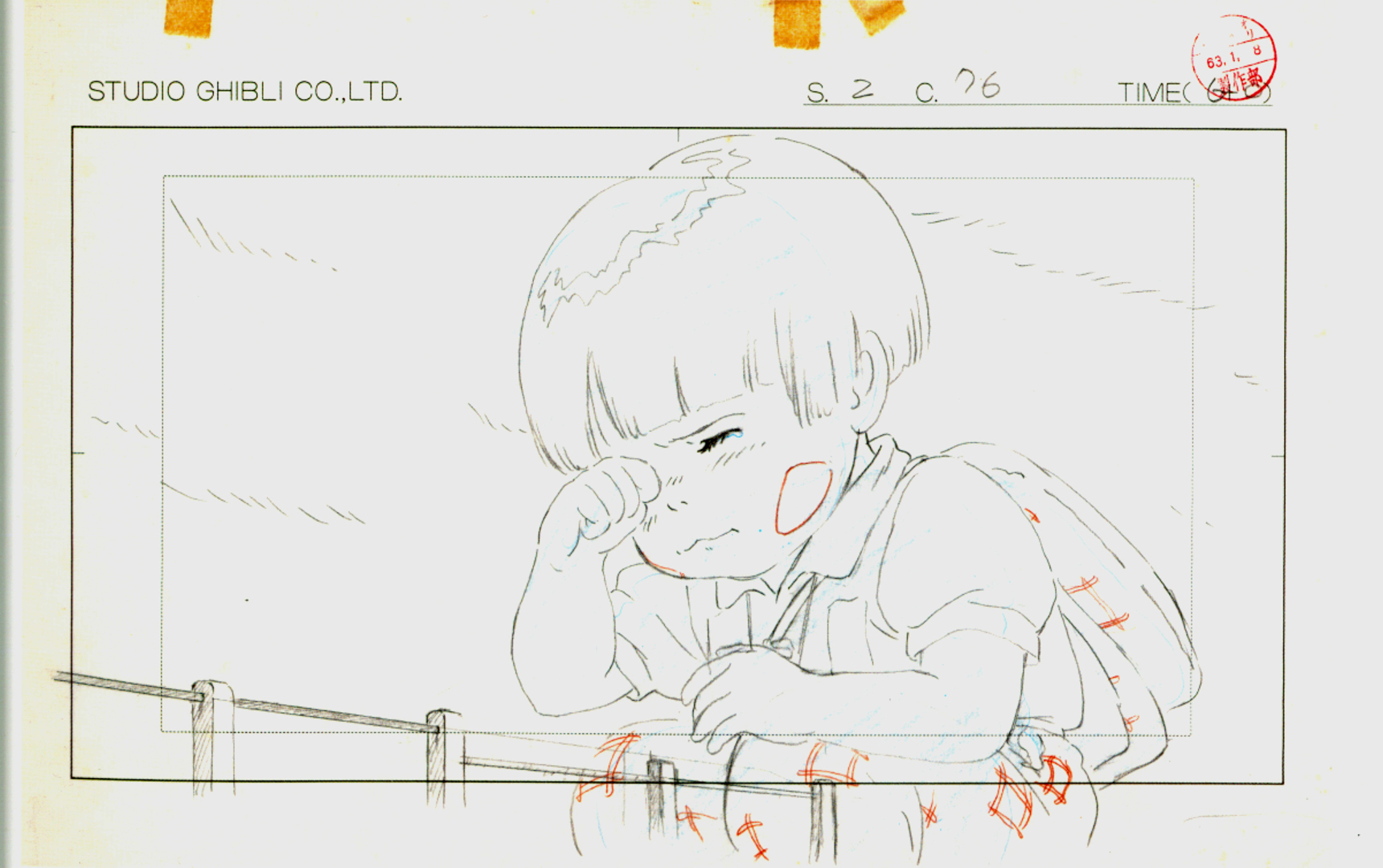

The first project affected by this would of course be Takahata’s Only Yesterday, a nostalgic low stakes piece that very appropriately mixes youth and adulthood. 27 year old office worker Taeko Okajima can’t seem to escape her various childhood memories as she visits the countryside during a holiday, creating an elegant duality that runs through this movie on all levels. The trainees of the first generation of true Ghibli-raised animators, which included the likes of Masashi Ando and Kenichi Yamada, had to live up to the outrageous demands of Takahata just like the studio’s old guard did. The result of everyone’s efforts was once again neatly divided in half: Taeko’s memories featured simple drawings and slightly exaggerated expressions, whereas the modern day footage strove for unheard of realism in expression with a focus on facial muscles and more restrained motion. Overall the animation didn’t quite achieve the milimetric precision of Grave of the Fireflies, but Takahata didn’t miss the chance to surpass himself when it came down to a certain iconic scene; the director had never gotten over how misleadingly effortless the act of cutting a piece of watermelon had been in Fireflies, and so ever since then he made animators pay lots of attention to the intricacies of cutting fruit. That contributed to one of the most memorable scenes in Only Yesterday, where the buildup to the family having a then exotic fruit like pineapple for the first time is increased tenfold by the expert portrayal of its preparation… which also makes their blatant yet restrained disappointment when eating unripe pineapple just hilarious. This scene is a perfect time capsule that sums up the most graceful of all Ghibli movies.

Animation aside though, the best application of the intertwined dual identity of this film is its color and background work. Infatuated with his work on Totoro, Takahata turned to painting legend Kazuo Oga as art directorArt Director (美術監督, bijutsu kantoku): The person in charge of the background art for the series. They draw many artboards that once approved by the series director serve as reference for the backgrounds throughout the series. Coordination within the art department is a must – setting and color designers must work together to craft a coherent world. for Only Yesterday, with a very precise demand: the childhood sequences had to feature the pale colors of memories, fading on the sides and only highlighting the points that caused a lasting impression on Taeko, while the modern day backdrops required for detailed realism. The contrast in this regard, equally apparent indoors and outside, made each time period immediately recognizable, allowing for a very playful approach to storytelling. At the same time, it was very revealing when it came to the protagonist’s psyche, elegantly telling the audience which parts of her memories truly stayed with her. Takahata had taken an element perceived to be secondary like backgrounds and made it into a major device, entirely justifying his decision to take the whole art team on a location scouting trip, something that rarely ever happens. The world will never forget how beautifully they captured the safflowers – which happen to be the reason the movie’s setting was chosen to begin with – and yet some people in the crew were left with regrets. To this date, Oga believes that they went overboard on the modern scenes, and that they could have evoked a sense of reality with less intricate backgrounds.

That aim for a more economic approach to realism after those experiences could be felt all over Pom Poko, Takahata’s next film that had Oga return as the art directorArt Director (美術監督, bijutsu kantoku): The person in charge of the background art for the series. They draw many artboards that once approved by the series director serve as reference for the backgrounds throughout the series. Coordination within the art department is a must – setting and color designers must work together to craft a coherent world.; aided by his knowledge of the location, Oga captured the essence of the setting throughout the seasons without relying on the excruciating detail from Only Yesterday’s present day footage – following a similar arc to Takahata himself, who also began distancing himself from the pseudo-photorealism he had been toying with for a couple of films. Pom Poko already sported cartoonier animation to fit its frenzy, and his next works went on to feature extremely stylized aesthetics. The overtly fantastical spin also enabled many inventive compositions and fun ideas, making this one of Takahata’s most visually rich pieces, at least when it comes to sheer diversity. In spite of that and strong reception within Japan at release however, this is another charming entry in his filmography that tends to be overlooked. Perhaps the world would be more accepting of it now, with The Eccentric Family having opened people’s eyes about the greatness of tanuki cartoons.

While it doesn’t break new ground in the same way as other Takahata titles, the way it brings some of his recurring interests to the foreground makes it an intriguing offering if you want to grasp his vision. By making a movie about what we leave behind as society advances, based on creatures of folklore to boot, he was able to incorporate imagery from one of his passions: Japanese scrolls, which he’s written entire books about and that he’s implied to share artistic bloodlines with anime. But the most interesting element in this pretend-documentary might be its poignant commentary on thoughtless progress at the cost of nature up to the 90s. Political messages had been part of his work as director ever since the Vietnam War undertones in Horus, and his beliefs about the relationship between humanity and nature kept making their way into his films – the conversations about farming life in Only Yesterday and Yanagawa’s very existence just to name a few – but they hadn’t been given as much narrative spotlight as in Pom Poko. In contrast with Miyazaki’s environmentalism, Takahata’s focus of attention is in the delicate balance between us and the Earth as a give-and-take relationship. One of the most illustrative anecdotes in that regard happened while he revisited Anne’s setting; Takahata was mesmerized by Upper Canada Village, a living historical museum of sorts recreating life as it were in a 19th century local village. The necessary collaboration with nature fascinated the director, who even wished Japan had a similar initiative, not as to convince people to return to the past but to show children the equilibrium we should strive for.

It’s fair to say that at this point, Takahata began to feel his work was already done. After decades of making anime, the prospect simply wasn’t all that exciting anymore. However, a big change was coming, not just for him but for the industry as a whole: digital production. Leaving cel behind opened up many possibilities to anime creators, and that’s a challenge he couldn’t pass up. But Takahata was one of a kind. Rather than simply embracing digital coloring, he challenged the fundamentals of production once more. No matter the changes in tech, anime has always been produced by overlaying character art and painted backgrounds, attempting to create a full picture with a feeling of cohesion. My Neighbors the Yamadas threw all preconceptions out the window and tried to become a sketch come to life; gags that would be drawn before the eyes of the audience, a minimalist style that would often do away with backgrounds altogether and create more organic shots where everything starts with the pencil of the animator, Momose’s ambitious CG experimentation that blended into the unassuming artstyle, and nuanced acting that didn’t feel at odds with the simplicity. Even narrative conventions were ignored, since the movie is an amusing and surprisingly heartfelt collection of 4 panel skits. Takahata fulfilled his desire to direct something that simply would make people smile in the form of a truly unique film.

Unfortunately, there was a price to pay for all that innovation. Ghibli, being an anime studio, is geared towards efficient production of anime following the standard procedure. Deviations can be accommodated for special scenes, but by outright rejecting the usual workflow, lots of new bottlenecks were created while at the same time artists in some departments had absolutely nothing to do. Takahata essentially forced people to learn new skills while at the same time many of the studio’s assets couldn’t be used, which left them in disarray. It’s no secret that, sensing how off-kilter everyone was once the time to produce Spirited Away arrived, Miyazaki made them swear they wouldn’t make a movie like that again. Now I would argue that in spite of everything they definitely succeeded… in artistic terms, that is. The revolutionary Yamadas was doomed from the get-go, since it lacks the established Ghibli identity that brings countless people to watch their films. Takahata was aware of that, but rather than be disappointed with the reaction of the audience, he seemed to have calmly accepted the sad reality. For an artist who valued pursuing new ways of expression there couldn’t be anything more discouraging than realizing he’d been trapped within his studio’s brand.

Would there be another Takahata work after that fiasco? For a long time the answer seemed to be no, seeing how he’d grown a bit disinterested with anime production – though not creation as a whole, as seen from his amusing contribution to the Winter Days anthology in 2003 that nicely follows up the usage of haiku poems in Yamadas. His career as director had started by reaching the peak of a model that proved not to be sustainable in the long run. Ever since then he had revolutionized the very way things are animated, validated new registers for anime creators, and even managed to throw the most powerful studio in town entirely off-balance with his unconventional ways. Both his triumphs and defeats had already reshaped the world of animation. However, a director’s sense of fulfillment doesn’t necessarily correlate with the way their fans feel, even if they work in the same company. And Ghibli’s young producer Yoshiaki Nishimura proved to be one obstinate fellow. It took him a year and a half of long meetings with Takahata to convince him to direct another movie. The year was 2005, and that film wouldn’t be released until fall of 2013, after multiple delays.

As documented in Isao Takahata and His Tale of the Princess Kaguya, those 8 years in the making were spent trying to conjure an impossible production. The director had only agreed to Nishimura’s idea on the basis of making something unlike any work the world had seen before, not really because he intended it to be his last but because that was his general attitude in the last stage of his career. He decided on an evolution from the approach seen in Yamadas to create something they nicknamed sketch style. The fundamental concept behind it was that quick pencil traces have an inherent energy that more careful drawings lose, so Takahata wanted to retain that passion by making a movie with no clean-up, that would integrate those rough lines into the animation rather than ironing them out. The process was spearheaded by Osamu Tanabe, whose work with Ghibli began by drawing in-betweensIn-betweens (動画, douga): Essentially filling the gaps left by the key animators and completing the animation. The genga is traced and fully cleaned up if it hadn't been, then the missing frames are drawn following the notes for timing and spacing. on Grave of the Fireflies and then went on to have increasingly more important roles in Takahata’s movies. In spite of his tremendous help defining the aesthetic, this entirely new approach had even the most experienced animators scratching their heads, but that was only one of the many obstacles in the way; a storyboardStoryboard (絵コンテ, ekonte): The blueprints of animation. A series of usually simple drawings serving as anime's visual script, drawn on special sheets with fields for the animation cut number, notes for the staff and the matching lines of dialogue. that took 4 years to be completed, watercolor backgrounds that had to be redone entirely if even a small detail was off, the lack of a color palette and decision to instead paint on a per-shot basis… Both his peers and the man himself began doubting if the project would come to fruition. But in Takahata’s last communal triumph, it did.

The Tale of Princess Kaguya began publicly screening on November 23, 2013. The result of Ghibli Studio 7’s brave effort was a movie I immediately surrendered myself to, one I still feel inadequate talking about. After having earned a reputation for himself as a calculating, logical, even cold director at times, Takahata’s final work turned Japan’s oldest tale into pure animated emotion. An artist who couldn’t draw – a talent in disguise? – left the world of animation with one final gift. This time around he wouldn’t trigger another paradigm shift in the industry, because his work had become incredibly specific by the end, but Kaguya holds immense value nonetheless. It’s not as if he was a particularly misunderstood creator, because his sincerity and well-documented happenings painted a clear picture. Perhaps due to the focus on just a few of his titles though, there’s a tendency to treat his approach as a constant. But as I’ve been saying, he seemed to evolve with each work, shifting his goals and the methods to achieve them. Takahata changed himself while he changed anime, and like many others, he also changed the way I look at not just anime but life in general.

Rest in peace, Isao Takahata.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

Thank you for this. It was a delight to read.

Thanks for the write up on Isao Takahata. I can always look to this site to write detailed and analyzed pieces on anime, esp. you, kVIN. Currently, I can`t find this kind of content anywhere else. Toshio Suzuki said it was sad because Isao Takahata had WIPs, could any of those be anime related? In Kingdom of Dreams and Madness, Suzuki also refers to his efforts to get Takahata to progress in Kaguya, Takahata was frustrated with Suzuki, saying something along the lines of, Why should I have to finish this film? Glad that he did. – I have one… Read more »

I don’t feel like in the last stage of his career he really thought in terms of something potentially being an anime, or any other format for that matter. It was only when he came up with a very specific new way to convey something that he regained the passion to start a project, which obviously he couldn’t be blamed for considering his age and experience. Maybe some of those ideas would have worked in animation form, had they found a new interesting way of expression. Also genga is key animation, so not quite the same as layouts even if… Read more »

Thank you. Very interesting article. What would you say is your favorite Takahata film?

I’ve changed my answer to this multiple times (and will probably keep switching in the future), but I think that while Kaguya is his strongest movie, Only Yesterday is the one that resonates with me the most at the moment. I’ve managed to convince some people to watch it for the first time with that post and that makes me very happy.

>The Ainu elements from the original story were forcefully removed and replaced by a Scandinavian setting deemed more appropriate for the masses, which makes its first US title The Little Norse Prince feel like a bitter betrayal. How unfortunate he, at the end, didn’t have the opportunity to make good of that by tackling the adaptation of one Ainu poem he was striving for (https://web.archive.org/web/20071017155214/http://ghibliworld.com:80/isaotakahatainterview.html). That, along so many other ideas he had but so little time to live and see them fulfilled, all due to his utmost attention to detail. Both a blessing and a curse for him and… Read more »

His filmography could have been much larger if he had been willing to compromise more, but then he wouldn’t have been Takahata. But I feel like we should be glad he was able to make as many delightful works, considering how much he disregarded all trends. Sometimes I just smile at the fact that something like Yamadas was made at all, as a movie of all things, sandwiched by Ghibli’s most popular brand-defining fantasy titles.

Thank you so much for this wonderful article! It really sums up what made Takahata special. As a huge fan myself, this article reminded me that I still have to check out the Kaguya documentary. (As well as 3000 Leagues and Anne, but that will take some time.)

By the way, have you read Takahata’s 映画を作りながら考えたこと? I have only skimmed through it so far, it seems to be incredibly insightful with detailed descriptions (often up to 50 pages) of every movie up to Gōshu/Gauche.

There’s even another volume that covers most of his work at Ghibli! Fortunately there are plenty of publications, documentaries and the likes that will help future generations understand just how important he was.

Thank you so, so much for writing this article. Not only was it incredibly interesting and informative, but also eye-opening. When I was finishing reading it, I wanted to cry (and still do). Not so much because of sadness over Takahata’s passing away, but more because of how overwhelmed I feel– in a good way, by all the different aspects you explained and how they’re related. There were even moments when I thought I wish I’d been there, how much I’d learn.. (I’m a 2d animation student). Sorry for the overly-personal comment, haha. Despite being a fan of Ghibli, and… Read more »

Thank you for this comment, honestly. The whole situation had me very emotional and getting it all out was relieving, so if made artists like you come to appreciate Takahata a little bit more, even better. Anytime I’ve returned to his work I’ve been able to find new aspects to it, making even more things just click. That logical core means that once you are able to isolate his train of thought, a new whole chunk of the work makes perfect sense, but due to that explosive inventiveness there’s just too many parts to it to get the full picture.… Read more »

“… while some iconic sequences started showcasing true momentum and volume, matching anime’s trend towards photographic realism that scholars like Yuichiro Oguro have documented. Its popularity then enabled new means of expression for creators who weren’t even involved in its production, as Takahata had proven this was a valid new canvas for animation. Grave of the Fireflies was a massive success even beyond the goals it had set for itself.”

Can you link me to where he documented that? I’m interested in the realistic movement of the late 80s in anime, so any other help is also appreciated!

It was in a talk with Inoue, where they put together that animation chart that has made the rounds a few times. The discussed trends and influences so it’s not like they went very in-depth on each period.

The original archive shared by the @tokyo_sks Twitter account isn’t available anymore, but both another copy ) and the translated one shared by HP at /a/ (

) and the translated one shared by HP at /a/ ( ) still are.

) still are.

I take my hat off, really excellent article. A pleasure to read.

This was an enjoyable read. I love both Miyazaki’s and Takahata’s works but on a personal level, I can relate more to Takahata’s.

Wonderful, wonderful post. Thank you.

Is there anywhere that I can read up more on the impact those three WMT shows?

Where did you take the picture of Takahata thanking Otsuka Yasuo?

Either from Joy Of Motion or the Ghibli Museum docu, which are the ones I references the most for those screenshots. I’d have to check but I assume it’s the former!