10 Years Since The Disappearance of Haruhi Suzumiya: An Eternal Legacy

The Disappearance of Haruhi Suzumiya was released 10 years ago today, on February 6, 2010. A decade later and despite the tragic losses, its legacy at Kyoto Animation and the industry altogether still endures.

It may be hard to imagine now if you’re a bit of a newcomer to this hobby, but there was a time when anime was practically synonymous with Haruhi. While the tremendous financial success is easy to measure even nowadays, its actual impact was much more profound than that, capable of changing an entire subculture and creating new gateways into anime. Haruhiism was kind of a joke, except it wasn’t. The titular character’s desire to find something special amidst the ordinary resonated with countless young viewers, inspiring them to seek more stories or even create them themselves; the latter group includes people like, for example, the author of the current season’s Keep Your Hands Off Eizouken. So of course, with that much success and enough material at their disposal, it didn’t take long for the staff to begin planning the next stage of Kyon’s adventures.

If you’ve got a good memory or are simply acquainted with what the series is like, you’ll know that the process wasn’t straightforward. Nothing about Haruhi ever is. In the early summer of 2007, around a year after the broadcast of the original TV series and right before the official confirmation that the anime would be continuing, producers and core staff were already deep amidst conversations about how to proceed further into Haruhi’s world. Multiple plot points were on the table – including a certain staff favorite by the name of The Disappearance of Haruhi Suzumiya, which they began constructing into around 7 TV anime episodes.

In the end, that’s not how things panned out at all. The team moved forward with an altered plan to rebroadcast the series with 14 new episodes mixed with the 14 original ones – and without properly announcing that, the Haruhi way – but Disappearance was deemed worthy of special treatment and thus became a theatrical project instead. By the time fans were greeted with the first new episode of Haruhi somewhat by surprise, the movie that the new broadcast was building up to had long since been written. And yes, that does indeed mean that the reviled Endless Eight arc wasn’t just doing the essential emotional groundwork for Nagato in the upcoming film, it also quite literally enabled its existence by filling a big gap in the TV series after Disappearance split off. To this day, it remains a misunderstood stroke of genius and luck.

However, the challenges didn’t end after the decision to make Disappearance into a movie – if anything, that only made things trickier. By that point, the studio had already earned a reputation for creating animation of the highest quality you could see on TV, but could they actually step up their game to match the large screen? Although nuance in acting and thorough polish is something that Kyoto Animation already achieved on the regular, there’s something special to the way that theatrical animation is constructed… or at least there was until everyone began throwing projects made with the same constraints as TV shows into cinemas, but that’s a topic for another day.

KyoAni had produced movies before… technically. 2009’s Last War of Heavenloids and Akutoloids passes the theatrical standards well enough because it happens to be the passion project of a genuine anime legend, but the truth is that it’s simply the definitive conclusion of an existing OVA series. You can look as far back as 1996 to find the first movie you could make a good case for as their theatrical debut: Shin Kimagure Orange Road: Summer’s Beginning, featuring none other than Haruhi’s general manager Tatsuya Ishihara as the sole unit director, and with all major animation and painting duties done by his crew at Kyoto. Interesting trivia aside, though, there’s no denying that The Disappearance of Haruhi Suzumiya was the first project that the studio built from the ground with the large screen in mind.

Had they been any other studio, the strategy would have been clear: contact freelance theatrical animation specialists to truly take Haruhi to the next level. But that’s not the KyoAni way. Their fully in-house method, the strength built on camaraderie with the staff they work with on every single project, they wouldn’t allow for that. So instead, they began a process of transformation of the studio as a whole that still has palpable consequences to this day. A series of seemingly small practices like getting all animation staff used to drawing every project on the larger sheets that would normally be reserved to movies, which over time led to feats like being capable of animating a title of A Silent Voice’s caliber and quality within six months. One of the secrets behind KyoAni’s enduring quality is that they tore down that wall and effectively make all their anime as if they were movies now; not exactly the same way because each project has its own circumstances and their best directors are mindful of details like the physical difference between TV and cinema layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists., but always keeping that uncompromising theatrical spirit.

While the aforementioned Ishihara had his hands full charting the course of Haruhi’s continuation, someone else was chosen to step in and lead the production itself. That person was none other than the late Yasuhiro Takemoto, the eternally undervalued backbone of the studio. While Naoko Yamada – unit director in the film – at least gets some credit for pushing KyoAni forward in terms of broadening what expression through animation means, Takemoto is rarely brought up, even though he was the ideologue behind the studio’s increase in sheer scope. For all his subtle qualities as a creator, Takemoto’s stern and ambitious personality led to very tangible results as well; it’s not a coincidence that Hyouka is a 22 episodes series with more footage than standard two cours anime, and that Disappearance was the longest anime movie upon first release, only bested overall by Final Yamato’s director’s cut. He was never one to let common sense in the way of his vision.

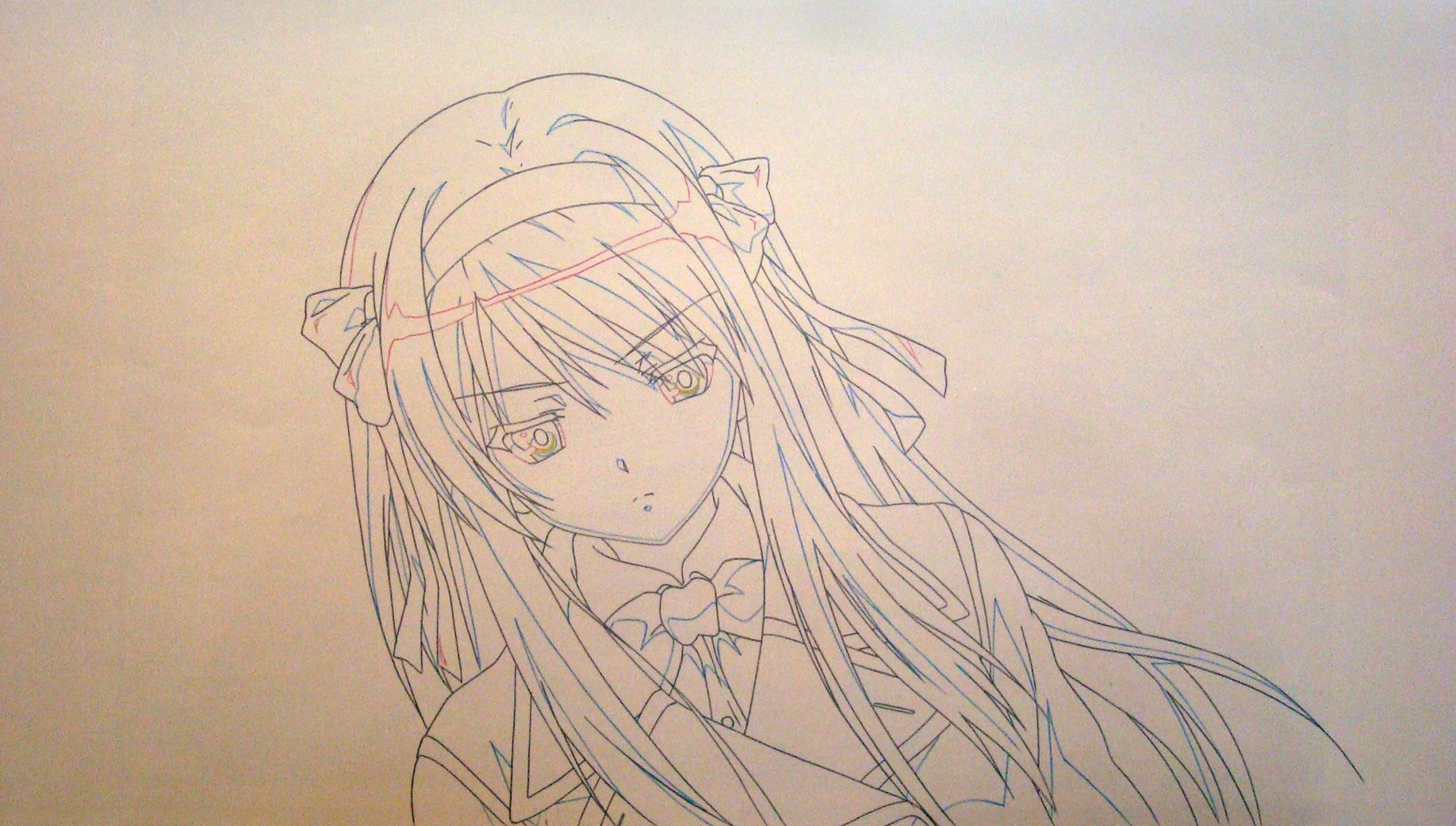

KyoAni’s transition into becoming a theatrical studio of sorts, especially in regards to what it means for the animation, would also have been impossible without a very special mentor. Yoshiji Kigami, the single most important animator in the studio’s history, supervised all the layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists. in their first few films, instructing the staff in what theatrical animation is all about. Using his experience on iconic movies like Akira and Grave of the Fireflies, Kigami looked over every single shot to make sure they were constructed in a way that fit the larger screen, carefully arranged so that the extra real state didn’t lead to empty visuals. Meanwhile, two chief supervisors would make sure the animation itself and the character art were up to par; Futoshi Nishiya addressed the former by correcting movement and body language from the rough animation cuts, while Shouko Ikeda stepped in right at the end to make sure the characters had a consistent enough look across the film. These split supervision duties – layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists. and specific aspects of the animation – have remained a KyoAni tradition for theatrical projects, where they have to pay extra attention not just to the quality but the way scenes are constructed.

Their efforts didn’t simply manifest in the form of a good movie, but also a superlative Haruhi one. Disappearance is in many ways the culmination of what the studio had been building up to: the kind of work that let them walk away from the franchise with a feeling of accomplishment even if it technically didn’t wrap up the narrative. It brilliantly summarized one of Haruhi’s greatest overarching qualities: its commitment. While author Nagaru Tanigawa appears to stumble into interesting ideas in a way that feels accidental sometimes, once he’s chosen a path he’ll follow its natural course no matter what, even if it involves unpleasant arguments or outright removing the most charismatic, titular character. Similarly, even his more questionable choices are properly followed through on and have consequences, rather than sweeping them all under the rug.

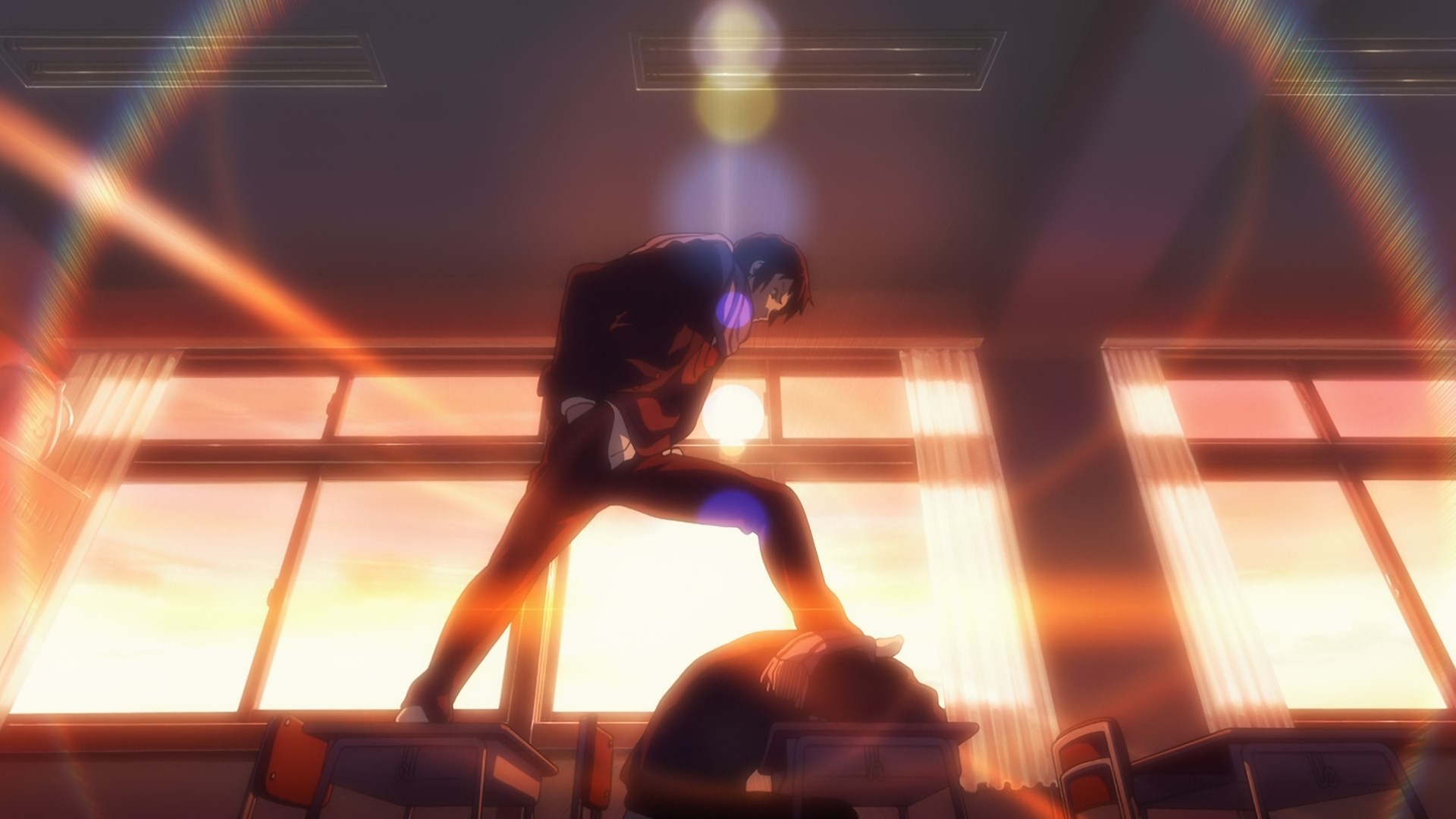

Disappearance is a movie that pulls back no punches in that regard, even during its quieter moments. The two middle acts of the film, storyboarded by Noriko Takao, are a master class in understated unpleasantness, a lifeless life depiction that Takemoto equated to a world without the Sun – which is to say, what Kyon’s everyday would be without Haruhi. The director considered the iconic scene where he revels against that to be the moment where Kyon truly became a protagonist. As a creator endlessly fascinated by the fragile side of male main characters that we rarely see in anime, it’s no wonder that the inner monologue where Kyon is forced to accept Haruhi as an inescapable weakness of his spoke so strongly to Takemoto.

A decade later, I can say that not every single aspect about Haruhi has aged well, but Disappearance has done so like fine wine – to the point that it’s almost a shame it’s so rooted in its franchise context, which makes it a more daunting prospect for new watchers. This was the project that began changing KyoAni, and in some ways, the industry as a whole; the current paradigm of latenight anime films would have been unimaginable back then, but thanks to the massive success that franchises like Haruhi and Macross Frontier had in the large screen, distributors realized that there was a new market about to boom. Looking back on the project 10 years after its release is painful because many of the people who were essential to its production are among the victims of last year’s arson attack, but one comforting truth remains: even if they’re gone, their legacy remains. And Disappearance embodies that.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

I hurt just thinking about all the incredible, talented folks we lost when that deranged psychopath did what he did, Takemoto probably the most. Everything that he ever touched had a kind of special, understated magic that sometimes seems to have been overlooked.

Thank you for this, kViN, now’s the perfect time for a rewatch.

Thanks for this wonderful article.

Great article kVin. Could I ask about how KyoAni and their recovery/rebuilding have been doing after the tragedy?

Hey, thanks for this. Although I’m more Free! demographics than Haruhi when it comes to explaining why I love KyoAni and always will, maybe I wouldn’t even have watched Free! if I wasn’t already a fan of series like Haruhi (of which I did watch all of Endless Eight as it aired, lol!), K-on!! or Clannad (esp. AS).

Disappearance is one of my few regrets. I first got into anime back when Haruhi really was synonymous with anime, but I ventured away from the medium for years, and I missed the Disappearance film. I’m torn whenever I think of it because I don’t think I would fully appreciate it without rewatching the second season of the TV series— as someone who dutifully watched through every episode of Endless Eight— yet I never feel up to that despite the strong desire to see the definitive entry of a series that was important both communally and personally. I wish I… Read more »