What Actually Is Anime Outsourcing? – The Historical Context And Current Reality Of Anime’s Life Support

Everyone knows what outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio. means on a basic level, but at the same time, few get how it works in anime—so here’s a summary of this practice’s historical context, the logistics at play, and the impact on the creative process of the cause and cure of many anime industry problems.

OutsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio. is an omnipresent practice in anime. One that is widely regarded by viewers as the cause of many of its problems, and yet hardly understood, even by those who are fairly familiar with how animation works. The basic principle is so simple—the main studio subcontracting work to other companies—that people just don’t stop and think what that actually entails in this industry, leading to a lot of assumptions based on half-truths and sometimes nasty, ahistorical nonsense. There’s no denying that outsourced episodes face particularly harsh challenges that often lead to the show taking a quality hit, but so is the fact that it’s not an inherently harmful practice. Given that this season we’ve seen an unusually high concentration of outsourced episodes that were as good if not better than the in-house ones on the likes of Slime 300, Bakuten, Nomad: Megalo Box 2, 86, or Dynazenon, it felt like the right time to address this topic.

The arrival of NUT-affiliated animator Shinichi Kurita in an episode of Megalo Box 2 outsourced to his studio recently gave the show a spark of loose fluidity that its main team, always focused on impact, would have never given it. This is a good example of outsourcing broadening an anime’s visual language.

First of all, we’re due some talk about the historical context, because that’s where the misunderstandings begin; both the idea that outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio. is a recent problem, or that it being a problem is a recent thing. It’s no exaggeration to say that outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio. has gone hand in hand with anime as we know it since its inception. 1963 saw the first TV anime in a recognizable form with Astro Boy: a long-form, serialized work that fully occupied a standard television slot. And thus, also in 1963, Osamu Tezuka’s Mushi Production had to face the fact that projects on that scale take a tremendous amount of work. Commercial anime was born to an in-house model, because a studio actually making the thing they intend to put out into the world is the most natural of models, but it immediately became obvious that such a thing just isn’t possible unless you plan things very carefully—something that this industry has never been known for.

By episode #34 of Astro Boy, the staff was so exhausted that Tezuka decided to grant everyone a bit of a break by subcontracting the production of the episode to Studio Zero. A reasonable-sounding idea, but it’s important to keep in mind that the company had only just been founded by a collective of mangaka; at the time including Shotaro Ishinomori, Jiro Tsunoda and his brother, the Fujiko Fujio duo, and Shinichi Suzuki as the only member with actual anime experience. Unsurprisingly, the episode lacked consistency not just when compared to the prior episodes but also on an internal level, with each idiosyncratic, essentially amateur animator doing their thing.

And their thing they did. It’s fun!

To say that Tezuka was unhappy with the result would be putting it mildly, and so retakes were issued to try to correct it up somewhat. Studio Zero never got entrusted with Astro Boy again, while this episode faded into the abyss and wasn’t even included in the show’s releases for decades. As a bit of a side note, there’s a lot of speculation linking Tezuka’s clear distaste of the episode with the fact that it nearly became lost media. Living legend Rintaro, who worked at Mushi Pro at the time, addressed the rumors by explaining that Tezuka was too mindful of other people’s works to ever throw it away on purpose, meaning that the situation must have been an archival failure for an episode that didn’t follow the regular production line. Now that’s another problem that has followed anime for all these years.

Was that bitter first experience enough to deter anime from relying on outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio., then? Of course not—it wasn’t even enough to stop Tezuka and company from doing so on Astro Boy. As proof of that, we’ve got episode #134 produced by Onishi Pro, and most notably, a whole stretch of the show that was subcontracted to P Productions. The core team at Mushi Pro had grown a bit tired of the series, and the studio had done them no favors by allowing 3-4 concurrent TV anime productions to pile up on their shoulders by 1965; one of them being Kimba the White Lion, which the staff generally favored because who wouldn’t want to work on this shiny new toy that was color TV anime. Tezuka relied on another set of acquaintances by having the folks at P Pro animate the show for a period of time that ended up being much longer than originally expected. Reports in this regard contradict themselves somewhat, but it ended up being around a whole year of subcontracted episodes in the end. Not exactly a minor contribution.

In summary, this very first example of anime outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio. led to consistency issues due to miscommunication and the reliance on a team that maybe wasn’t fully prepared, as well as overproduction causing an unreasonably large chunk of a show to be shipped somewhere else—any of this sound familiar? Because it should.

Some of you might be thinking that, as similar as that sounds to anime’s current woes, something has fundamentally changed for the worse: these early examples at least consist of a creator entrusting work to direct acquaintances whom they thought could do a good job with it, whereas nowadays it’s all about subcontracting work overseas to cut costs. If that’s your train of thought, you’re sort of wrong, in both directions at that. The vast majority of full outsourcing—a concept I’ll get around to in a bit—still occurs within Japan, and the subcontracting of work treated as lesser like in-betweening and painting to Southeast Asia, Korea, and China dates further back than you might think. It’s still in the 60s that you can find the earliest examples of Japanese production subcontracting minor work overseas on the likes of Ougon Bat and Humanoid Monster Bem; a curiosity back then, but by all means a sign of things to come.

By the mid 70s, this had already become such a widespread practice—see Toei Douga trying to sidestep their domestic labor disputes by relying on Korean studios—that it led to many major studios sending experienced anime creators to those countries to instruct local staff and build partnerships with them. As nice as the idea of direct mentorship sounds, we shouldn’t kid ourselves about the ultimately exploitative goals of those relationships they built. Keep in mind that the only time when Japanese studios have lessened their reliance on those companies is the stretch during the late 80s and early 90s where the socioeconomic context allowed those support studios to ask for higher rates, which tells you that it’s not talent or even manpower they’ve been prioritizing for decades.

Now, the point of underlining that the issues that plagued outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio. in its early days are very similar to the ones we see nowadays isn’t to say that nothing has changed; if anything, anime changes so fast that every industry dissection needs to be revisited every 5 years or so because something will have surely changed. Instead, the point was to exemplify that the potential problems are as inherent to it as “having less work for the main team” is as an advantage, so of course that an increasingly messier industry would come to exacerbate them. The same greed that promotes a race to the bottom for workers, as well as the need to subcontract work in the first place due to overproduction. And of course, the same communication issues born from not having one team together at the same place—be it because they’re one street over, or one whole ocean away from the core team.

Toei’s aforementioned dodginess continued as the increasing rates in Korea made them turn their eye towards the Philipines, where they acquired a local studio that would become Toei Phils—integrating them into their pipeline, where they don’t qualify as outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio. anymore. Nowadays, Phils handles around 70% of Toei’s total workload through various stages of the production process. The quality of the episodes they fully animate is generally low, not for a lack of talent, but because they’re underpaid and made to work in even worse situations than their supposed peers. With the right circumstances, their work can really shine.

These dynamics have shaped anime’s outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio. practices as we see them nowadays, which begs the question I’ve been dancing around for too long: exactly what is anime outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio.? Language makes things needlessly complicated here, because the practice of subcontracting segments of the workload to a specific studio is not really what we talk about when we discuss outsourced anime, even though that is by all means a smaller form of it. Why make that separation? For starters, because every single studio not named Kyoto Animation does that every single week, but also because there is a more significant practice: subcontracting the production of an entire episode, making it so that for all intents and purposes, the show just so happens to be made by a different studio that week. This practice receives the name of gross (グロス), where the studio that it’s subcontracted to would be the gross-uke (グロス請け) in reference to how they take it all up. Here on the SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog, we tend to refer to those instances as full outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio., in an attempt to stress out that the production changes hands on a pretty fundamental level.

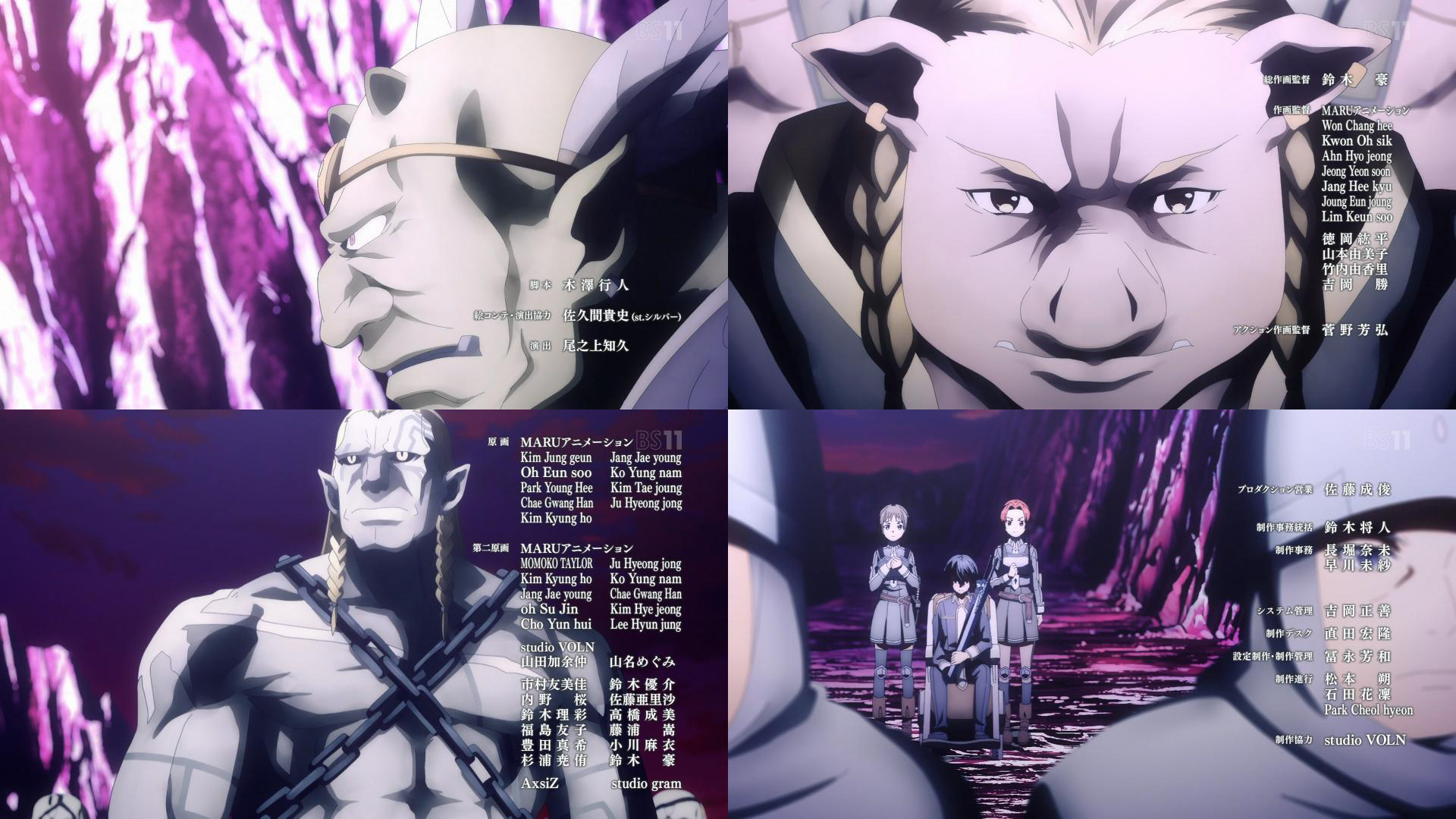

So, what does that exactly entail, then? The subcontracted studio will most likely work off a storyboardStoryboard (絵コンテ, ekonte): The blueprints of animation. A series of usually simple drawings serving as anime's visual script, drawn on special sheets with fields for the animation cut number, notes for the staff and the matching lines of dialogue. drawn by someone in the core team, be it an in-house director or someone they’re acquainted with. It’s also possible for them to storyboardStoryboard (絵コンテ, ekonte): The blueprints of animation. A series of usually simple drawings serving as anime's visual script, drawn on special sheets with fields for the animation cut number, notes for the staff and the matching lines of dialogue. it themselves, which would be indicative of deliberate talent-seeking by the main studio since the pre-production stages; a type of deal that represents the greatest potential of outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio., but that sadly has never been the norm. Either way, once given the storyboardStoryboard (絵コンテ, ekonte): The blueprints of animation. A series of usually simple drawings serving as anime's visual script, drawn on special sheets with fields for the animation cut number, notes for the staff and the matching lines of dialogue., it’s on them to do as anime studios do: gather a team of key animators as well as their supervisors, then ensure that it gets in-betweened and painted as well. All of this, coordinated by their own management staff of course, and ultimately in the hands of an episode director of their own. To avoid major aesthetic clashes with the rest of the work, roles like the background art and compositing are usually handled by the regular crew, though there are minor variations to this model depending on the specific circumstances of the project.

The proper delivery of materials, especially for overseas outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio., is a big deal. Just a few years ago, episode #18 of Magi aired on TV with blatantly missing in-betweens for a key scene featuring Mor’s dance because they had been lost in the shipping process from China. It made for a pretty miserable viewing experience, but as you can see, it got fixed in the BD/DVD release. Even nowadays and despite the increasing digitization of the process, there are companies specifically in charge of scanning and delivering the materials to make sure things don’t go too wrong.

And who does that? For the most part, it’s support studios—a category that, frankly speaking, doesn’t actually exist. Let me explain: even though they’re legally all the same type of company, anime production studios come in many sizes and forms. Some large, some small, some specialized in one role, others packing every department you could ever need in anime production. And, even though a lot of people would assume otherwise, there’s one thing that isn’t common to all of them: the ability to make their own anime. Be it because they’re newcomers still figuring things out, or because they’ve grown to be comfortable in a supporting position, plenty of studios spend years doing subcontracted work for other companies, both chunks of it and this full outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio. we’re talking about. For a lack of a better name, that’s what we refer to as support studios, which play a key role in the anime ecosystem.

There have been notable support studios across the decades, starting as early as we left off in the history lesson earlier; Nakamura Pro, founded in 1974 as part of the wave that followed Mushi Pro’s collapse, has remained a constant presence in the background of anime ever since then, maintaining an important relationship with renowned studios like Sunrise for all these years. Some support studios with lengthy lifespans like that have grown to be very large, but in a specialized way befitting their particular needs; such was the case of studio Wanpack, which grew to have nearly a hundred animators—more than most studios that actually create their own titles—over the decades it supported others, before the death of its founder led to the studio’s disappearance in 2018. While the idea of an outsourced episode has such a poor reputation, stealthy and reliable support studios like Snowdrop have continued to exist, as well as ones that can genuinely bump up the quality of any production they show up on, such as Makaria has been doing. Long-running titles in particular demand the existence of studios like that, as it would be impossible for them to sustain a feasible staff rotation otherwise.

Studio Nexus, still acting solely as a support studio at the time, played one of the best-known outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio. roles in modern times by handling the production of 9 episodes out of Re:Zero‘s original 25 episodes run. They provided directorial talent, animators, painters, and of course the management staff to make all of that work. If you’ve seen the second season produced after their departure, chances are that you’ve already noticed how important Nexus was to its original stability.

As you might already know, however, support studios aren’t the only ones undertaking these full outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio. jobs. The examples I gave at the very start of this piece include episodes produced by the likes of WIT, CloverWorks, and Madhouse—some of the most popular names in the industry, whom you could assume have no business doing assistance tasks. So, why do that, when their plate is already so full? The answer is simple: bottlenecks. All studios are very busy, causing an increase in the need for outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio. in the first place, but that doesn’t mean everyone is occupied at the same time, because anime production is a long process involving people in pretty different positions. And since contracts don’t exactly pay well, anime production companies are always on the lookout for side jobs like this, meaning that they tend to be relatively happy to accept an acquaintance’s call for help to fully produce an episode, while the rest of the studio is busy with something else.

It’s also worth noting that as we implied earlier, most studios start their activities with support work. Even if you’re splitting off an existing anime production company and immediately find yourself surrounded by an experienced crew, it’s hard to make your own works right off the bat, for both financial and creative reasons. Which is why, even for studios that have gone on to become creative powerhouses of their own over time, acting as a support studio in their early stages is an extremely common trait; well-known is the fact that Kyoto Animation was one of the greatest support studios over decades, or that Trigger’s actual debut was on individual episodes for Aniplex titles such as The Idolmaster #17. If you ever grow curious about a particular studio, hunting down such instances can be a fascinating exercise.

Out of the couple dozen outsourced episodes of FMA Brotherhood that kept its production stable. 7 of them were produced by historic studio Telecom, a legend when it comes to supporting other companies’ projects across the whole world. While the likes of Hisao Yokobori contributed some spectacular animation, the studio also took over tasks like background art and compositing that usually remain within the core team. A big weight lifted off the shoulders of the whole team, without sacrificing a bit of quality—anime’s outsourcing at its best.

This has covered the what, the how, the who of anime outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio., but given how much of a nightmare this process often turns out to be, it feels important to return to the why. While in concept this is simple, it turns out to be another source of misunderstandings by mixing up cause and effect. Does the industry target less affluent countries in SEA for a ridiculous amount of minor—but massive by sheer weight—work precisely because their rates are low? Of course, we’ve already demonstrated that by pointing out that they immediately look for even poorer countries if asked to pay higher rates. Is anime outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio. done to cut costs, then? The answer is no, because it costs more than keeping things in-house.

Even if the individual rates are even lower in such situations, the need to contract more companies, more middlemen, to spend more time and effort in a workflow that is naturally less fluid often ends up making such episodes costlier; if not directly on a purely financial sense, absolutely when you add up the extra effort that goes into managing them. Whenever this type of sentiment is echoed across the industry, fans tend to be cynical of it, because the idea that outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio. in anime happens first and foremost to cut costs is that deeply rooted. For some first hand information, we actually covered a mismanaged production where that dilemma came into play: the production staff presented an outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio. plan to the studio’s CEO because they knew it would be necessary to get the job done, but he declined it to avoid increasing the costs, only accepting to do it when it was way too late. Ideally, all studios would love to do as much work in-house as possible. It’s only when they’re put in situations where they must subcontract work that they decide to do it in the cheapest way possible—the order matters!

And it’s that idea of in-house episodes that leads to some final misconceptions I’d like to address. As you’ve been seeing across this piece, there’s no perfect dichotomy between in-house episodes where everything is done by the studio’s employees and outsourced ones where it’s the subcontracted company’s personnel handling 100% of the work. As things currently stand, in-house episodes at right about any studio still rely on freelancers and people employed by other studios to do a lot of the work. At the same time, you can also find outlier outsourced episodes that slot more core staff into them than in-house efforts elsewhere, increasing the show’s stylistic cohesion in the process; such is the case for Dynazenon, another of the aforementioned positive examples from this current season. There is also the case of specific animation assistance as opposed to production assistance (作画協力 versus 制作協力), which can imply that the subcontracting was specifically focused on the animation process, without handling everything else that surrounds that creative process. Which is to say: keep an eye on the credits and what the creators say if you want to know the specifics dynamics of a project, because even if you understand the theory of outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio., things are often more complex in the real world.

What’s the takeaway from all of this, then? For starters, there’s the fact that anime outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio. is neither new nor inherently a problem. Thoroughly positive examples, as well as benign neutral ones, have continued to exist to this day, but tend to be ignored because most viewers have stigmatized the practice to the point that they’ll never even consider that that one cool episode might have been subcontracted elsewhere. On the other hand, the worsening conditions have made the inherent problems stand out even more, as the collapsing schedules exacerbate the issues of remote production models. We’re in a situation where many outsourced episodes turn out very poorly, and yet it’s only with liberal outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio. practices that the current level of output can be sustained at all.

The brunt of the blame for all this tends to go to studios overseas, even though most high responsibility tasks remain in Japan; if you see people vehemently throwing foreign workers under the bus, keep in mind that their motivation is likely not the quality of the work but something darker. Instead, I encourage you to direct the blame where it should usually be: to the higher-ups demanding an impossible number of anime a year, because they’re the ones who’ve ruined yet another practice; remember how 2nd key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. was invented to allow a certain ace action animator to participate in more scenes, before overproduction turned it into a means to rescue rushed layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists.? Funny how the problems usually come from that same direction, huh.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

Tezuka Productions and MAPPA co-produced the animation for Dororo. In instances like this, is less outsourcing necessary because two studios share the burden? Or is there still a large amount of outsourcing regardless?

Co-productions between two 2D studios are a way to make the workload more feasible from the get-go, which greatly reduces the need for full outsourcing – though you’ll still find cases where it happens anyway. In Dororo’s case, they got away with having every episode produced in-house (16.5 episodes at MAPPA, 7.5 at Tezuka Productions) but being the types of studios those two are, an unreasonable amount of work was still subcontracted to people all over the world. Which is to say, this approach helps, but it’s not going to magically fix structural problems at a studio.

Between this and the American animation industry, so much actual animation happens in Korea.

Excellent article!

Very informative article! I’ve been an anime fan for 20+ years, and even though I’m not as into it as I used to be, I did occasionally think about outsourcing…never knew much about it. I remember watching episodes of Inuyasha back in the early 2000s and noticing how the animation looked slightly different all the time. Then when I became a more seasoned anime fan some years later and learned about KyoAni, I was like “hey, some of those good quality Inuyasha episodes really look like they were made by KyoAni.” And turns out they were, lol. Same with Pokemon,… Read more »

Great article, hope you’ll do another one on the reliance of freelancers.

Also, there’s so much animation going to Korea I hope they’re okay.

It varies from studio to studio, I would assume. I know the studio who works on CN cartoons Sunmin, is fairly well off, and Nelson Shin of AKOM, despite the studio’s less than reputable quality, has mentioned they’re not anywhere near as bad as the norm (though part of that seems to stem from the fact that all they do these days is just their long-standing contract for The Simpsons, when back in the 80s and 90s, they were one of those names you’d see almost everywhere, from Batman and Transformers, to X-Men, which had a fair bit of outsourcing… Read more »

Nice article subcontracting studios are really a intresting thing i have a blog of a Chinese guy tho who visited so many subcontracting studios of Tokyo and wuxi and a thing about studios of wuxi was that some of them operate in single rooms lol

Surprised you didn’t mention Vietnam with how prevalent it is in terms of outsourced work.

You can consider it included in the many SEA references, since they’re one of the many countries playing a big role there.

Great article! Just for clarification, who are the “higher-ups” that are demanding more anime? Are they the producers? And are studios not allowed to say no to a project even if it strains the studio?

That would be (executive) producers from corporations that want to hit their targets, yeah. Studios can always refuse pitches in theory, but in practice it’s more complicated. Their margins are thin, so they’re often in a position where they want to accept as many projects as reasonably possible. And to ensure that continues to happen in the long run, that leads to them accepting even projects they know will put them in a beyond reasonable position, because you want to be known as a reliable studio that’s always there to accept tricky jobs. It’s a broken system.

Do the publishers like Shueisha or Kadokawa have to involve in the production committee? I mean they already own the copyrights of one work, along with the author, so I think they don’t have to invest as it allows them to cut risk while still receiving the profit? I’m sorry if I have some misunderstandings here.

You’re right! They don’t “have to”, it’s just a relatively low-risk option that often is seen as beneficial. Lets them exert even more control, and they get even more money out of it if the anime itself is a hit.