The Long Quest To Fix Anime’s Collapsing Mentorship: The Young Animator Training Project, And Its Legacy 10 Years After LWA & Death Billiards

The collapse of anime’s mentorship systems and the attempts to fix them aren’t new. At its peak 10 years ago, the Young Animator Training Project produced Little Witch Academia and Death Billiards while raising new talent—but did it succeed, and what’s their legacy now?

The collapse of anime’s mentorship systems is a major issue we’ve tackled before, trying to illustrate its many effects and the specific struggles that both veterans and newcomers have to face. As a country with a very active 2D animation scene, Japan does actually have plenty of options to study animation in a traditional setting. Some of those are strictly geared towards fostering the creative spirit, while other courses try to offer a more practical look at what creating commercial animation is like, but the truth is that even the latter rarely prepare up-and-coming artists for the quirks of the industry. Though it’s understandable that animation courses at university art programs aren’t geared towards the sometimes depressingly restrictive reality of anime production, even the so-called anime academies appear to lack effective practical training—which is why proactive industry members are so happy to publish their own guides and even hold lectures if possible.

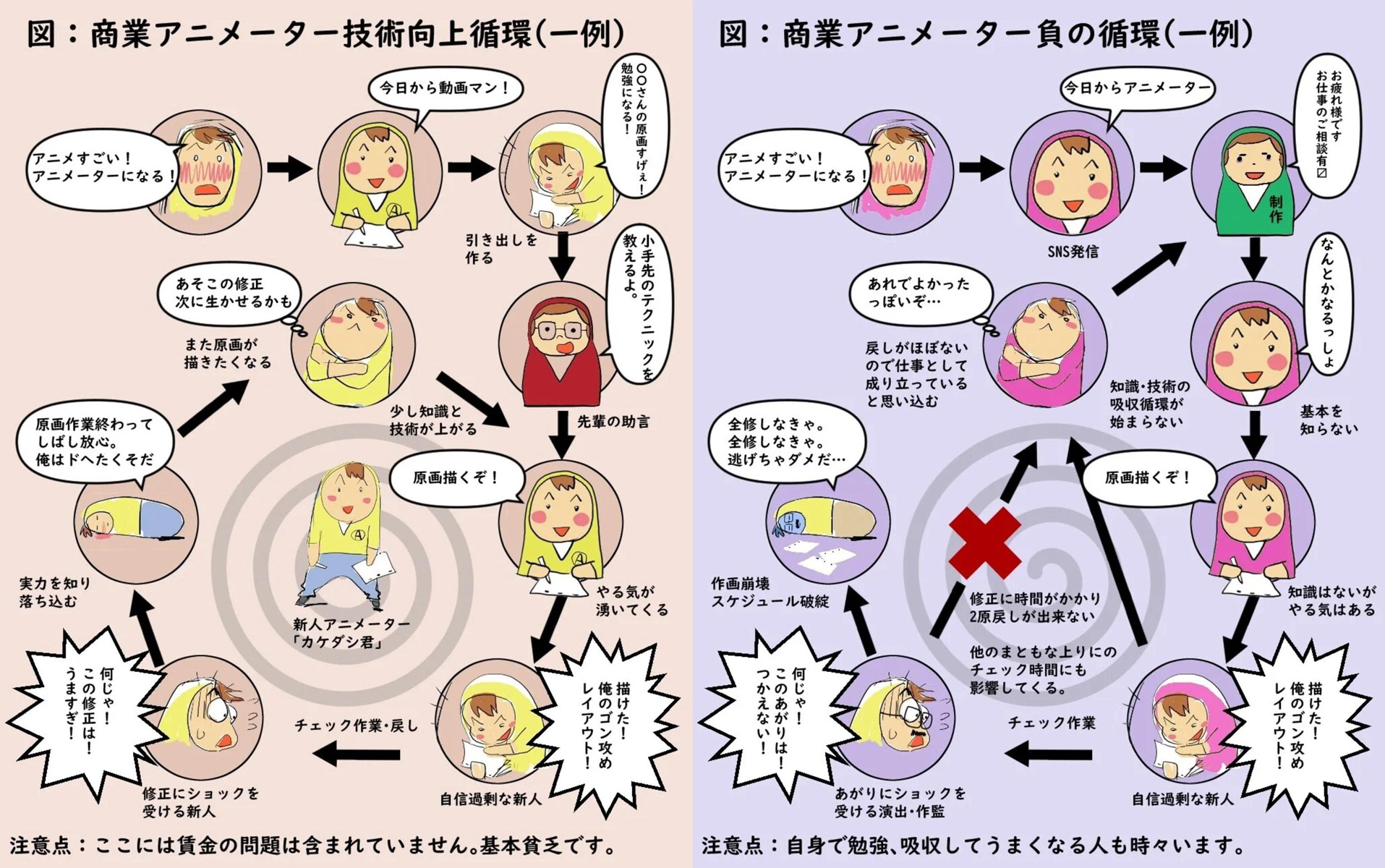

What creators like that are attempting to do is to individually address widening systemic holes, which are now present where support structures used to be. While never an ideal system, anime got away well enough with apprenticeship and on-the-job training. I believe that trying to understand why commercial Japanese animation settled on its pipeline through creative, cost, and efficiency lenses alone misses that it deliberately created chains of knowledge to pass down; essentially no one joining the job was prepared for it—to a larger degree than that is already common—and yet the production model still perpetuated that accumulation of knowledge. But as many veterans now lament, that cycle has completely fallen apart.

How did it get to this point, though? The truth is that the reasons are many, and not all of them are inherently negative. The barrier of entry to the anime industry was first leapfrogged by the progenitor webgenWebgen (web系): Popular term to refer to the mostly young digital animators that have been joining the professional anime industry as of late; their most notable artists started off gaining attention through gifs and fanmade animations online, hence web generation. It encompasses various waves of artists at this point so it's hardly one generation anymore, but the term has stuck. animators, handpicked by visionaries like the late Osamu Kobayashi; he saw those young artists sharing their work online as diamonds in the rough, valuing the roughness perhaps more than the diamond itself, so he recruited them before they underwent traditional training. The tremendous success that webgen ringleaders in various positions of the production process achieved since then has normalized this practice, and the internationalization of anime production—not through perfunctory subcontracting but to seek talent over the globe—has completely demolished whatever remained of those barriers. On paper, anime now channels more diverse creative voices than ever.

In reality, though, things are obviously a lot more complicated. The arrival of all this very raw talent has been precipitated by desperation, as the worsening schedules and unreasonable expectations asphyxiate most studios to the point of scrambling for manpower; which is to say, hardly an environment where those newcomers can be dedicated the time and energy for the mentorship they dearly need. While these young individuals might be sought because of their talent, overseas subcontracting for more pragmatic reasons has also been growing for so long that most studios have allowed themselves to become internally weak. When major levels of outsourcing become such a regular practice, companies operate under the assumption that it’s going to happen no matter what, and over time that leads to a decline of their in-house strength—especially departments that handle tasks seen as lesser, which as it turns out, are often those that used to be the basis of anime’s on-site training.

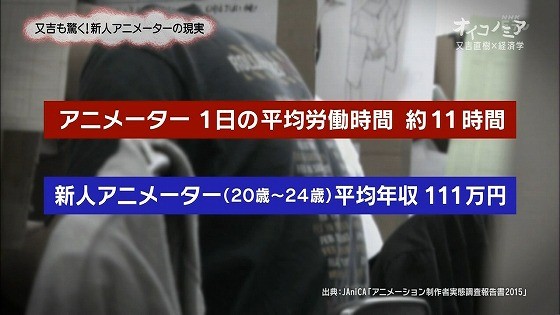

Traditional animation careers had young artists join studios as in-betweening trainees, allowing them to learn the ropes by tracing the work of experienced key animators while receiving specific guidance from veterans in their douga department. Although in many cases in-betweening was a temporary role, there is essentially no choice to be made in that regard now. The complete stagnation of the already shamefully low per drawing rates, their only source of income in most cases, means that they must either rush to move up or quit entirely—reflected in the massive attrition rates.

After trending in this direction for so long, the perception of the role has warped so badly that some industry members have had to take a stance in its favor; a baffling development to anyone who is aware that all the animation we see on screen is actually this team’s work. But through subcontracting en masse, and by making the labor situation so untenable, work that once held a duality of a useful training step and highly specific but valid career path is now a crapshoot on both ends: it’s not seen as a real job, and it sure isn’t respected as a learning opportunity. The figure of veteran in-betweeners is being reduced to very few people at the studio if any at all, and the forceful rushing through the process negatively impacts the training situation as well. With policies such as charging a desk rent fee to young animators who don’t pass their key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. tests fast enough, the environment is clearly not one of healthy mentorship.

The situation isn’t any better at the key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. stage, be it for those who have followed this traditional path or the even more unprepared aspiring artists who can now easily sidestep it. The same interconnected woes of scheduling and labor get in the way, and new issues specific to their situation arise. The undergoing fragmentation of the animation process in particular is one that many veterans are pointing their fingers to. With anime getting chopped into increasingly smaller bits and a lack of continuity in the workflow, hugely important learning experiences like the corrections you were supposed to receive from veteran supervisors are fading away; they may be sent to someone else just to finish the shot ASAP, the supervisor may be just as green and only there just because a body was needed, or it may not even make financial sense for the animator who drew the layout to finish the potentially tricky key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. for such low pay. Many issues have come to get in the way of the traditional training systems, at a time when they’re more needed than ever.

If these specific issues sound familiar, it’s because they should be. While some specific ways in which this manifests are still recent developments—like the role of 2nd key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. getting out of hand in this spiral of production fragmentation—it’s a constant decline that has brought the anime industry to its limits. And that has been going on for long enough that we’ve been able to see governmental projects, hardly the swiftest to roll out, rise and fall as the situation has kept on getting worse. Project A, Anime Mirai, Anime Tamago, and Anime no Tane are names that evoke the seeds of a prosperous future for Japanese animation, and they’re all iterations of the same long-lasting campaign: the Young Animator Training Project.

When it first launched in 2010 through Project A, this initiative already cited overproduction, deteriorating schedules, and extensive outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio. as major impediments to anime’s on-the-job training. The Japanese Animation Creators Association, widely known as JAniCA, had identified that problem and managed to make use of a then new law to promote the arts and culture to secure the subsidies for this project. The model they established then has shifted in participants, scope, and certainly success, but the structure remains the same: every year, 4 anime studios receive 38 million yen to produce a short film, in a production process where a handful of young animators are the centerpiece. Incidentally, the fact that what was once meant to be a comfortable production budget hasn’t changed a millimeter in over a decade sums up what working in the anime industry is like.

Those young animators, who must be in their 20s still and have a limited amount of experience, undergo an enhanced version of that traditional on-the-job training that anime studios no longer undertake properly. For about half a year, the youngsters fully dedicate themselves to the creation of this work—making it a focal point that they all share the same physical workplace, as fostering in-house culture is also a goal. To emphasize their learning process, there’s a constant back and forth between them and the director, or the lead supervisor in case the project isn’t captained by an animator. Though the rules’ relative vagueness allows those veterans to dye these works with their style, the theory says that they’re not supposed to fully correct shots themselves, but rather explain what was wrong so that it’s the youngsters who truly pen the key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style.. Considering that this precedes the real crisis of fragmented animation production and the loss of corrections as guidance, their foresight in this regard is commendable.

Since animating a full short film can be a daunting prospect for a small group of young artists, and not all directors are animation masters themselves, the program properly establishes the figure of the veteran animator. Although they don’t actively lead the younglings, the veterans are meant to give advice whenever they’re approached with a question, and they will handle a fair share of cuts in the short film if necessary. Extra clauses establish that they should be involved in tasks other than their own animation job, to ensure that they get a broader look at the production process. That’s not something that could ever be taken for granted, and in a time of rushed, fragmented, remote production that makes it harder for up-and-coming artists to get a grasp of the broader picture, initiatives like this certainly have a point. All these efforts at the studio and surrounding companies are complemented by outside lectures held by JAniCA themselves; again, ones that don’t just cover animation theory, but also practical lessons like actual photographyPhotography (撮影, Satsuei): The marriage of elements produced by different departments into a finished picture, involving filtering to make it more harmonious. A name inherited from the past, when cameras were actually used during this process. to enhance their composition sensibilities. While it can be a harsh half a year for various reasons, it’s packed with learning opportunities in ways that no regular project at those studios is.

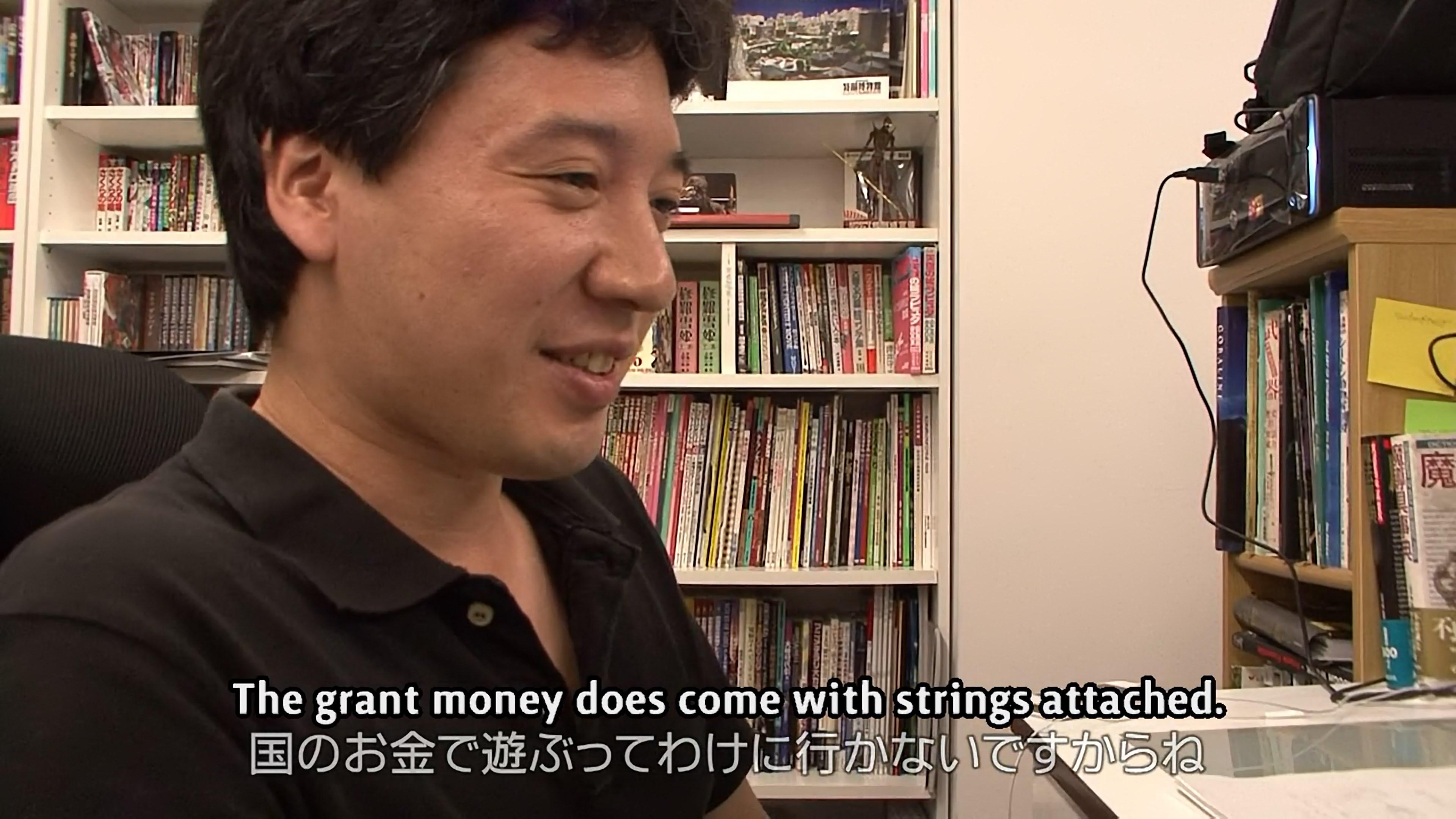

For as noble as the explicit goals of the Young Animator Training Project sound, it’s also worth considering its understated ones as well. How could a project like this get rolling in the first place? The Japanese government has been made aware of the labor issues in anime and yet they’ve never really stepped in to address them. If this isn’t really motivated by worry about the well-being of creators, and certainly not because politicians felt a sudden love for the arts, then you have to look at one thing they do value: anime as a product with worldwide popularity. Much like some infamous Cool Japan initiatives, and despite not officially listing it as a goal, the Young Animator Training Project is also meant to secure the future of a leading export; after all, the majority of directors and original anime creators are animators themselves, so a failure to raise new generations also endangers the product on that top level.

That attitude is baked into the project’s rules, in ways that might not be obvious at first glance. It’s worth noting that barring minor exceptions, they’re all supposed to create original works—and most unusually, the directors themselves must at least co-write the script. Even during its heyday, when these short films were led by all sorts of renowned artists, pitches by new directors were clearly prioritized—be it up-and-coming creators, or veteran animators willing to step up and begin leading their own works. In many ways, this is also the Directors And Authors Training Project, as having a supply of those is very important to the people calling the shots.

If this sounds a bit too cynical, keep in mind that some veteran animators have had issues with the underlying attitudes of the project before it even launched. In an unrelated chat about animation authorship, one such industry member pointed out that in the early stages of this project, the idea of crediting animators specifically for their every cut was pitched. The idea was deemed somewhat redundant given that the production model already emphasizes the figures of the young artists, but what rubbed them the wrong way was the higher-ups admitting that rather than training, what was most important there was creating better products to sell. While a good deed done with less than ideal intentions remains positive nonetheless, it feels important to also keep in mind these less altruistic and creator-driven aspects of the project, especially if you want to understand the trajectory of this program over the years.

So, how has the Young Animator Training Project fared then, not just as a mentorship program, but as a yearly animated anthology? Early on, it was nothing short of fascinating. As previously stated, these short films would regularly be led by creators who hadn’t made a name for themselves as directors yet, but who rightfully held a strong reputation among their peers. The very first batch for Project A sums up the collection of talent the project was capable of gathering, as well as all the potential outcomes.

Masayuki Yoshihara was a renowned animator thanks to his iconic contributions to the likes of Yu Yu Hakusho, but while he’d timidly worked up the directorial ladder as an assistant for Production IG titles, it wasn’t until Bannou Yasai Ninninman that he got to create something of his own—immediately exhibiting the whimsical charm that enamored so many people in Uchouten Kazoku. Although in their cases this didn’t lead to a similarly notable directorial career, Project A also featured works by other notable animators giving the directorial seat a spin: Production IG titan Kazuchika Kise, as well as Teiichi Takiguchi, whom we recently highlighted as the best realist ufotable animator no one knows. Complemented by a household name in kid-friendly animation like Mitsuru Hongo, this first year set a strong precedent.

The following iterations of the program—especially in its Anime Mirai period, from 2012 to 2015—followed up on that promise. Even if not all 4 short films were bound to hit to the same degree, the diversity of scenarios really felt like the leading creators were exploiting this uniquely free opportunity. Perhaps unsurprisingly given JAniCA’s connections, those directorial seats continued to be occupied by both artists with great cache and highly promising newcomers; including the likes of Yasuhiro Yoshiura, Ayumu Watanabe, Kazuhide Tomonaga, Naoyuki Onda, Tatsuya Yoshihara, and Kazuaki Imai just in those first few years. And just as importantly given the nature of the project, time has proved that their selection of young talent and nurturing of it could be very effective. Even sakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. fans might not be aware that the young animators mentored in that period include currently beloved names like Norifumi Kugai, Ryo Araki, Shu Sugita, Hidekazu Ebina, Maiko Kobayashi, Kengo Saito, Maki Kawake, Emi Ota, Shingo Takenaka, and Izumi Seguchi, just to give a few names that showcase diverse animation talents.

Even among those successful early years, one iteration of the Young Animator Training Project towers above the rest. Released 10 years ago in March 2013, both the immediate impact and the legacy of Anime Mirai 2012 make it stand out as a close-to-ideal execution of the potential held by this program; and mind you, that’s even accounting for the short film by the aforementioned Tatsuya Yoshihara-led short film being an unplanned replacement due to studio Pierrot plans falling apart. Despite accidents like that, Anime Mirai 2012 launched the directorial careers of some of the most exciting figures in anime right now, it provided invaluable learning experiences to an even larger number of current industry stars, and it established teams so tightly knit that they stand to this day. Even as standalone works, its offerings met so much success that most Young Animator Training Project short films to ever get a sequel come from this one batch. As you can probably guess, much of this is owed to two specific works: Little Witch Academia and Death Billiards.

The former made lots of noise upon announcement, and has remained the most popular product of this entire program ever since. Animation superstar Yoh Yoshinari made his directorial debut with a world of wizardry that draws direct parallels between traditional animation and magical powers seen as outdated and lesser—the perfect energy to bring into a program like this. Both in this short film and the two sequels it later received, Yoshinari’s sensibilities enable a perfect marriage between a western Saturday morning cartoon and distinctly anime quirkiness; in its script, and also through the effects animation that plays a key role in its depiction of magic. LWA is the very definition of charming, and if you’ve somehow never seen it, there are few recommendations this easy to issue.

In contrast to LWA’s wholesome scenario, Death Billiards uses a bar in limbo as the setting to explore preconceptions and moral failings that tickled the fancy of beloved director Yuzuru Tachikawa—mostly just known as a great action storyboarder then, as he had yet to lead projects like Mob Psycho 100. While that premise may make it sound like Tachikawa’s idea was humorless, the result is anything but. Death Billiards, and especially its TV sequel Death Parade, leave plenty of room for goofy scenarios in the midst of exploring moral ambiguity. In that regard, its sleek style and sheer entertainment value make it an equally easy recommendation, even if you don’t happen to buy the philosophy that Tachikawa puts on display.

Leaving aside their charm as short films, these two projects are very interesting in how they embody the potential range behind the idea of training young animators—to the point of having to bend the rules in spots. The Young Animator Training Project attempts to regulate this by stipulating certain ranges of experience for the youngsters who apply; those have shifted slightly over the years, but generally, they want to avoid having to deal with complete newbies by demanding at least half a year of proper in-betweening experience, and also attempt to cap the range on the opposite end by keeping their key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. portfolio under 3 years.

Many artists have had their key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. debut throughout this program, as it’s obvious that there is much to learn for fresh artists in a position like that. However, there’s no desire to bother with the absolute newbies, to the point where the program will turn a blind eye to the in-betweening entirely as long as it’s not ostensibly outsourced overseas. It’s notable how they will gloat that the vast majority of past participant animators they surveyed remain on the job despite anime’s harsh attrition rates… despite not tracking the in-betweening teams, which is where that brutal attrition occurs; essentially, the industry equivalent of praising a low number of deaths in childbirth by interviewing healthy teenagers.

It’s on the upper end that things get more interesting. While everyone would agree that inexperienced artists have much to learn, fewer realize that even those who have been around for years can greatly benefit from mentorship by amazing veterans. LWA’s lineup of young animators featured artists in their 20s who’d first grown acquainted with the crew back in their days at Gainax, and had since then taken their unique paths; even working on manual, non-creative work for years in some cases. With perhaps the exception of Hisao Dendo, who has distanced himself from the team and instead orbits more around the likes of OLM, they’ve all gone to become important figures in Trigger productions. Shuhei Handa is now a recurring designer and chief animation directorChief Animation Director (総作画監督, Sou Sakuga Kantoku): Often an overall credit that tends to be in the hands of the character designer, though as of late messy projects with multiple Chief ADs have increased in number; moreso than the regular animation directors, their job is to ensure the characters look like they're supposed to. Consistency is their goal, which they will enforce as much as they want (and can)., Yuto Kaneko has grown to be one of their ace animators, and Shouta Sannomiya still lends them his multitalented hands when needed—and all of them had little key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. experience heading into LWA.

Among them, Masaru Sakamoto somewhat stands out. While he’s not much older than his peers, he was certainly more experienced heading into this project, to the point where it takes a very generous interpretation to sneak him under the restriction of 3 years max as a key animator. Sakamoto had in fact already been promoted to animation directionAnimation Direction (作画監督, sakuga kantoku): The artists supervising the quality and consistency of the animation itself. They might correct cuts that deviate from the designs too much if they see it fit, but their job is mostly to ensure the motion is up to par while not looking too rough. Plenty of specialized Animation Direction roles exist – mecha, effects, creatures, all focused in one particular recurring element. duties, but it was precisely that which made him realize that he could do with a better grasp of the fundamentals. Under Yoshinari’s strict, but also fair and empathetic surveillance—they all appreciated how he’d try to introduce their own adlibs into sequences even as he demanded quality-related retakes—he matured into a reliable animator who can alternate between cool exaggeration and comfortable posing. As of writing this, the latest work by studio TRIGGER is Gridman Universe, the culmination of a cult hit franchise that feels like it draws from both extreme ends of those animation sensibilities. Its character designer and chief animation directorChief Animation Director (総作画監督, Sou Sakuga Kantoku): Often an overall credit that tends to be in the hands of the character designer, though as of late messy projects with multiple Chief ADs have increased in number; moreso than the regular animation directors, their job is to ensure the characters look like they're supposed to. Consistency is their goal, which they will enforce as much as they want (and can).? One Masaru Sakamoto.

Death Parade’s team showcases similar, if anything more extreme patterns. All but a couple of its youngsters made their key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. debut in this work, and they’ve since then gone on to become respected figures in the industry who tend to work together to this day. Perhaps excepting Tatsuhiko Komatsu, the names of Izumi Murakami, Boya Liang, Ai Ogata, Eiko Mishima, and Naoko Minamii are ones you’ve come across in unique, sometimes outstanding productions. And among them, another person with a distinct background—and maybe more experience than the rules wanted—really stands out. Aya Suzuki is a renowned figure in worldwide animation circles; she has experience in theatrical animation all over the globe, has been holding animation lectures for many years, provides specialized interpretation services when needed, and even has major studios come to her to ask for various pieces of advice. And somehow, multiple years into an already outstanding career at the time, she found herself as one of those young animators.

Suzuki used those many skills of hers to make her way into the production of The Illusionist, after coinciding with its director Sylvain Chomet in an event where she volunteered as a translator. In the four years she spent in its production, she contributed to the long storyboarding process, became a de facto assistant supervising animator, and made an effort to contribute as a regular animator as well. After its release in 2010, she eventually tried her luck by messaging a few Japanese creators for a job opportunity. And out of them all, it was none other than the legendary Satoshi Kon who showed interest. After absentmindedly applying as an in-betweener, Suzuki found herselfappointed as a key animator for The Dreaming Machine. Kon’s unfortunate passing has kept the movie unfinished to this day, but Suzuki continued to attract the attention of Japan’s highest caliber of directors.

First it was Mamoru Hosoda, who entrusted her with Wolf Children, and through an amusing series of coincidences, she found herself contacted by Ghibli to work on Hayao Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises. It was only then that she returned to Madhouse for a stint as a young animator; you know, the very natural progression of being a senior animator alongside the greatest animation directors and then acting as a trainee.

Amusing contrasts aside, though, Suzuki’s experience does prove that even someone with that cache stood to learn something valuable in the right context. Having first worked in the UK, she wasn’t used to the Japanese pipeline at all, so ideas like establishing the basics of the camera, the eyelevel, and so on were a skillset she simply didn’t have. Her transition into anime happening through Kon’s work also allowed her to sidestep this, as the meticulous director had grown tired of having to correct other people’s layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists. at this point in his career, so he drew them himself to begin with. If you intend to continue working on Japanese animation, though, that’s an aspect you eventually have to master—and having an opportunity like this within her first few years dealing with anime’s idiosyncrasies was a great way to address those specific issues.

Suzuki had grown acquainted with Ei Inoue, as he too was slated to work alongside Kon in The Dreaming Machine. While she worked on Wolf Children, Inoue happened to visit the studio, and swung by her desk to invite her to the studio he was working with. That was none other than Ghibli, and as fate has it, they were going to hold a screening for The Illusionist—the movie Suzuki had worked on for years. After watching it with them and growing acquainted with the likes of Takahata, she later found herself getting invited to Miyazaki’s new film.

If the close relationship that most of LWA’s crew maintained—not just for its sequels, but also other Yoshinari works and TRIGGER titles in general—deserves a shout-out, then Death Billiard’s has earned it even more. As we pointed out when writing about the origins of the unique, very politely charged DECA-DENCE, the entire existence of Studio NUT can be traced back to this animator training project. Producer Takuya Tsunoki got a taste of what it is like to create crazy works alongside someone like Tachikawa, and quickly went on to create his own studio; hence the allusion to madness by naming the company NUT, and not the foul reason you’re thinking of.

After making that decision, Tsunoki’s ways of assembling a crew for it could be summed up with “simply hire Death Billiard’s crew again.” From character designer Shinichi Kurita to then production assistantProduction Assistant (制作進行, Seisaku Shinkou): Effectively the lowest ranking 'producer' role, and yet an essential cog in the system. They check and carry around the materials, and contact the dozens upon dozens of artists required to get an episode finished. Usually handling multiple episodes of the shows they're involved with. Kei Miura, they’ve essentially all gathered together again. And of course, that includes the animators they once mentored. Minamii and Mishima are now recurring animators and supervisors in their works, while Liang, Ogata, and Murakami also hold various design responsibilities. Even Suzuki, whose unique career keeps her too busy for TV anime work, has kept somehow influencing the team. Back during the production of Death Parade, Tachikawa essentially tried to bribe her by proposing to include dancing in its opening as he knew of her preferences. Even though Suzuki couldn’t work on it in the end, the iconic bizarre sequence remains nonetheless. These tight animators and surrounding veterans continue to show up in his new works like DECA-DENCE and the recent Blue Giant, but also right about every other NUT project to this day.

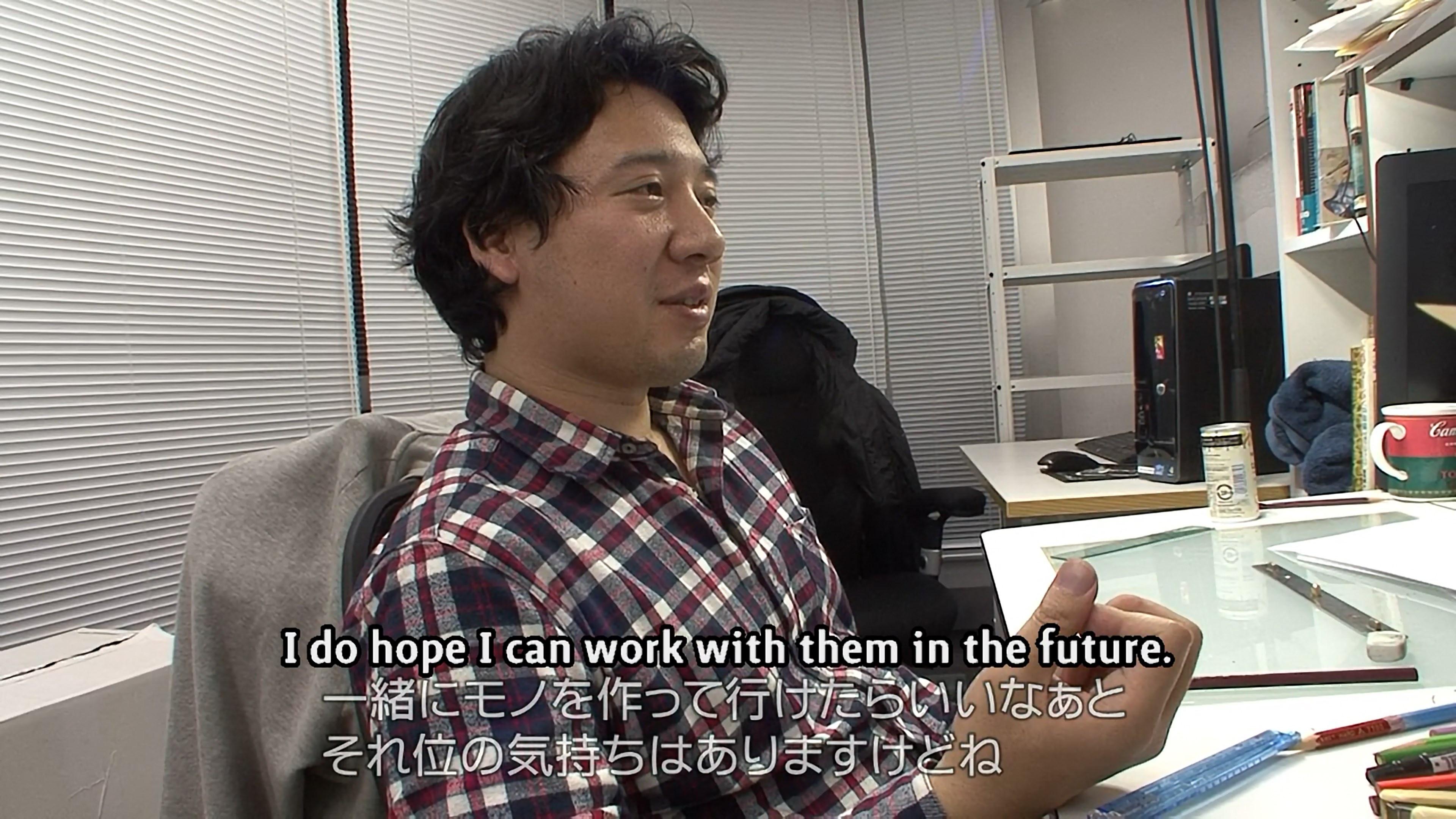

At the very end of Little Witch Academia’s making of feature, Yoshinari was asked if he’d come to like those young animators. After pondering about it for a while, he answered that he’d have to spend some more time with them to be able to tell. Having seen many young artists with potential forced out of the industry before they could blossom, Yoshinari hoped that they’d keep at it, and that they’d be able to work together in the future. A whole 10 years later, and as scattered as individuals in a freelance-based industry can appear, most of them still do show up to work with him whenever possible.

Even if you never bought it as a grand solution, which was clearly never in the cards given its limited scope, it’s hard to call the Young Animator Training Project a success. For as commendable as its core idea is, the execution of the program has been iffy, sometimes tainted, and eventually faded into irrelevance as it has distanced itself from creators. For all the praise we’ve thrown at the first era of the program, its deflation has been so thorough that even people who paid attention to it then likely don’t know that it’s still going on under different branding. With the switch to the Anime Tamago brand, its organization transferred to The Association of Japanese Animation AJA, a much more business-minded entity. While its origins have kept it linked to JAniCA-adjacent creative figures, the studio and project selection took a nosedive after this distance between the program and the collective of artists was established, making interesting pitches much rarer. And of course, it didn’t help that they switched to 50% fully 3DCG productions, which further pissed off animators—not because they hold a grudge against their CGi peers, but because this program was built from the ground to address very specific issues 2D animators face.

In contrast to that messy legacy, what does feel like a resounding success is the tangible positive effects and lasting bonds that we’ve highlighted today. Be it these cases of LWA and Death Billiards we’ve examined more at length, or the fact that sakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. superstar Yoshimichi Kameda now sits at WIT alongside friends he worked with in the delightful Paroru’s Future Island, there’s no denying that the Young Animator Training Project has done some great things for anime. For its future then, and the present now.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

There’s a small typo jut before you talk about Dream Machine, it should be herself, not himself. Great read!

You’re absolutely right, fixed!

Is change “subjective”?

Another entry into the “Remember back when I said anime was fucked? Still is! ” series.

Great write up. Particularly enjoyed the section focused on Ai Suzuki, who I’d never heard of before. What an interesting career path she’s had.

Fantastic read! More content like this is always welcome

10 years already! ‘Madre mía’, where did the time go?

One day you are waiting for some information to drop on an animemirai livestream presentation to discuss it at the /anime/ textboard, and the next you are here pondering about the crumbling Japanese animation production line going worse than ever.

Remember scrounging for tweets from Daisuke Okeda, or waiting even for episodes of NHK WORLD‘s imagine-nation to air and see if they had something new about the project? I certainly do.

Anyway, it is funny in retrospect how critic Ryūsuke Hikawa, within an evaluation of the project tasked by the ACA itself, nails the pin exactly on the problems derived from higher resolution lineart complexity and lack of a virtuous feedback cycle from supervisors, and still praises higher cels counts for the sake of it as a positive outcome; when economy of resources, and clever limiting to achieve healthy efficiency, are more necessary for the well-being of workers on the program and by extension the industry as a whole. That mentality inside the evaluators themselves shows that the program seemed more like an attempt at creating simple cog replacements for the machinery, instead of rewarding a more intelligent (see as “creative”) use of scarce human resources on an aging society overall.

One thing I personally would have liked to see from the initiative —when it was at its top— was tackling some riskier themes, given the fresh and bold perspective you can attach to the actual “young” qualifier; if the ACA gave them as much liberties as any allowed TV or film content had like Mr. Okeda implied, then it could have birthed ideas more akin to some of Japan Anima(tor)’s Exhibition works —obvious gap in mastery of the respective staffs involved notwithstanding—.

I love The Illusionist, a highly underrated film

I have a question: does this collapse in mentorship (and interesting layouts) only apply to Japan? Are other countries like China and South Korea able to pass down the techniques they’ve either learned or reinvented from anime?

Amazing article, even though I barely know a thing about any of these guys. Funny too.

also i think “less altruistic and creator-drive” is supposed be “creator-driven”.

Are Animenotane projects available for anyone to see? I remember avidly following the projects from 2010 to 2016, but after that they got harder and harder to find.

Thanks for the article.