Systemic Lack Of Training, “Convenient” Technological Advances, And The Destruction Of Technique & Knowledge In The Anime Industry

As the anime industry fails to properly train new generations of creators, “convenient” technological advances (whether good or not in their own right) have accelerated the loss of technique, fundamentals, and knowledge among the workforce. This is how veterans and newcomers face an already devastating issue that only stands to get worse.

When asked about the future of the anime industry in an interview for Kyoto College, veteran director Tatsuya Ishihara took a moment to ponder about the recent craze around—and fury against—the potential role of AI in animation. While many (not all) artists have expressed their worries and pushed back against aspects like the exploitation of people’s work without consent, cynical studio figureheads have been much more receptive to its adoption.

Production IG and Studio WIT CEO George Wada, notorious for an aggressive production stance and making overwork something between a point of pride and a joke, is ironically quick to invoke poor working conditions to justify his decisions or simply lie to unaware audiences to earn their sympathy. It’s no surprise, then, that he’s one to embrace AI as an inevitable force of good, to fight against brutal schedules imposed by a nebulous other. Mind you, those aren’t simply thoughtless answers given during conventions, as he already partnered with Netflix to have Studio WIT produce a short film where a portion of the backgrounds were generated through AI; judging by the results, an experiment in creating something that is visually and morally hideous in an equal manner. Other studio presidents cut from the same cloth, such as MAPPA’s Manabu Otsuka, have repeatedly stated that they consider AI worth pursuing when their application in anime is feasible. In eyes like his, this will be a way to produce anime with smaller teams—something you apparently can’t achieve with healthier schedules and better control of the scope of your projects and studio altogether, against all evidence that proves that is possible.

In contrast to that, Ishihara—who may not be as high on the ladder but still is KyoAni’s current veteran leader and a member of the company’s board of directors—was anxious about the potential consequences of embracing tech like this. He first pointed at the continuous mentorship of younger artists, the act of passing down techniques from generation to generation, as the main reason behind the studio’s consistently high-quality work. Technological disruptions can help us bypass challenges that once demanded the application of those carefully fostered techniques, but in his experience, that is a double-edged sword. To illustrate it, he brought up the depiction of one of his hobbies: train animation. Once upon a time, they were all drawn traditionally, but with the adoption of CGi people embraced that less cumbersome alternative… until virtually no one was able to draw them by hand anymore. Ishihara’s fear is to live in a world where increasingly fewer things can be expressed—not just by hand, but altogether in a way, because the choice of material is an important factor in what your work evokes.

It’s worth noting that Ishihara is no Luddite, as someone who has made an art out of the emulation of real photographic lenses in digital animation. What he is expressing worry for here, though, is the dangerous partnership between convenient technological advances—whether those are genuinely positive or not in their own right—and the failure to continue passing down anime’s accumulated knowledge and traditional techniques. And he’s saying this at a time when the industry’s systems of training have completely collapsed, with the mechanical canaries in the robot mines long dead, and with plenty of other industry members already complaining about having to face the consequences of that loss of institutional knowledge.

You’re likely already aware that the collapse of anime mentorship has been a recurring conversation within the industry, as we’ve echoed it on this site for years. It has persisted for long enough to transform from a potential worry for the future to a disaster with palpable consequences in the present, and future prospects only appear grimmer. We’ve already approached the topic from its relationship with the fragmentation of the production process, we’ve spoken at length about the impact it has already had over the animation layouts and thus anime’s immersive qualities according to industry veterans, and spoken about the issues with programs that tried to address these systemic issues—present even in individually brilliant works.

When talking about the skillset required in the industry, it’s always important to keep in mind that working in anime doesn’t simply test the artistic merits of someone’s work, or even their technical skill in a vacuum. The job is all about understanding the industry’s quirks, counterintuitive as they may appear, and being able to work around them without creating too much friction. If you’re a brilliant artist but lack the awareness of the production process at large, that will severely limit what you can accomplish in the commercial space, likely meaning you’d be better off in a small indie framework. Those who don’t have the speed to keep up with the pace of production, a factor even in more orderly projects, will struggle even if their eventual output is great; having the speed but not the mindset to somewhat consistently face the desk is also an issue that great veteran mentors point to as a common downfall. Even if you check all those boxes, lacking the specific knowledge about the tricks anime is built upon—how to abbreviate walk cycles, drawing satisfying flutter/nabiki, and so on—will exhaust you and lead to more costly, less effective work. And conversely, those who commit too strongly to the monotony of those mechanical shortcuts at the cost of creativity are at risk of burning out.

This is to say that, even at a time when it was common to join the anime industry after undergoing some form of traditional training, the expectation was that newcomers weren’t really prepared for the job. This led to the creation of anime-specific courses to bring some people up to speed, but even those don’t truly capture the real dynamics of the job. Instead, the industry is built around on-the-job training, with processes that have the newcomers trace over the lines of more experienced artists, receive their direct corrections, and other means of absorbing the type of institutional knowledge that once accumulated at studios. Artistic fundamentals, handy techniques, and the very attitude to minimize the mental and physical toll of the job are key aspects that were passed down naturally in a cycle of knowledge that the industry has now broken; once again, thanks to Ryoji Masuyama for that easy to understand graphic, as well as for all his work to remedy such issues.

In place of that collapsing mentorship system, the industry has seen various developments to make up for the gradual loss of the knowledge required to keep anime going. There have been individual initiatives like the Masuyama’s, larger programs like the Young Animators Training Course we discussed in a previous piece, and more broadly, massive technological advances have been embraced to make the job easier. Sure, those won’t bring back those fading classic fundamentals, but could they make it possible to bypass challenges, and even pave the path towards new forms of expression?

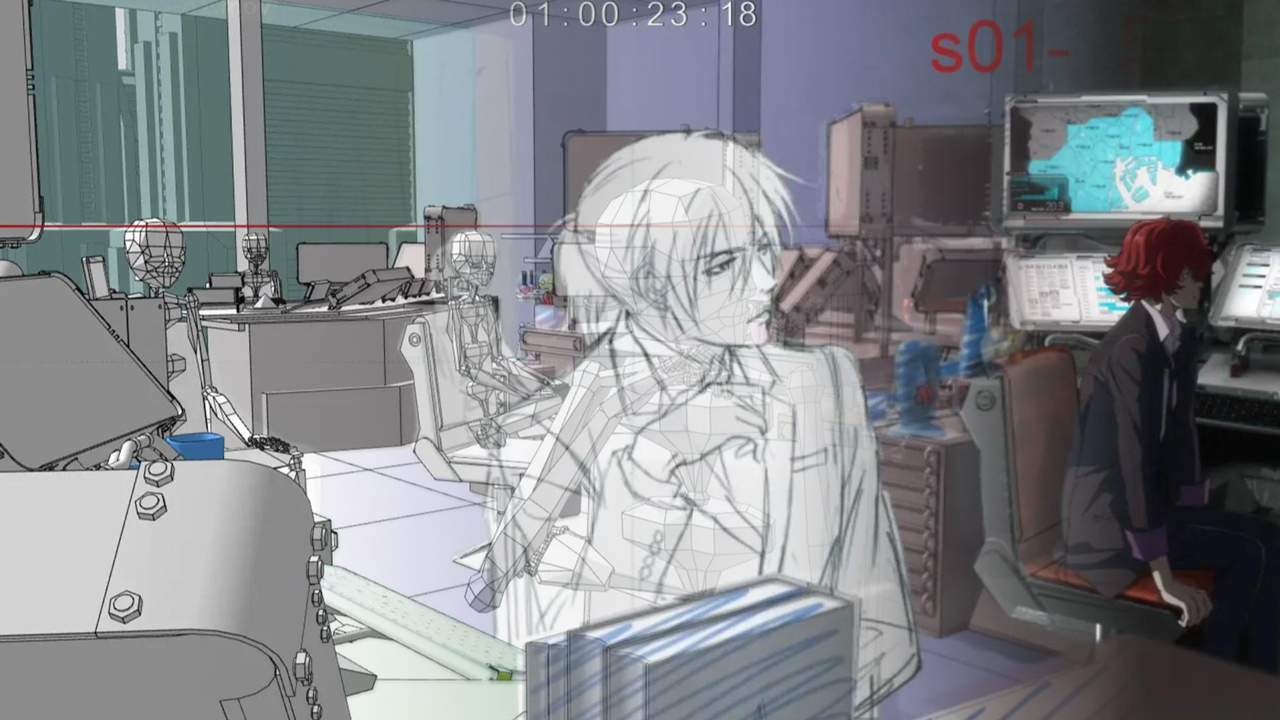

Although the longer answer is a lot more complicated, it’s undeniable that it has achieved those things. The gradual digitalization of the animation process has led to many quality of life improvements in day-to-day tasks, at least in theory; from the ability to quickly preview how your animation is looking to the ease of undoing one specific action across the whole process, the handiness of digital tools is demonstrable. Where things always get messier, however, is when contextualizing those technological advances with the real-world consequences of the change of paradigm that they contribute to. If we look back at the early days of digital anime—which is to say, with essentially all animation still being drawn on paper and simply colored and processed digitally—that taste of convenient technology was already accompanied by the industry’s output skyrocketing. While it is indeed helpful to not always be bound to the restrictions of physical materials, that was offset by making everyone much busier after removing the bottlenecks of the cel process. That is the broader outlook that you must consider when assessing changes in the industry.

Applied to a more current stage of the industry, the change that perhaps best illustrates this dangerous relationship between tech advancements and the labor situation in anime is the webgenWebgen (web系): Popular term to refer to the mostly young digital animators that have been joining the professional anime industry as of late; their most notable artists started off gaining attention through gifs and fanmade animations online, hence web generation. It encompasses various waves of artists at this point so it's hardly one generation anymore, but the term has stuck. revolution; one where there isn’t such direct causality between the tech itself and the worsening of those conditions, but where those two aspects are still inseparable. Although the discourse often approaches webgenWebgen (web系): Popular term to refer to the mostly young digital animators that have been joining the professional anime industry as of late; their most notable artists started off gaining attention through gifs and fanmade animations online, hence web generation. It encompasses various waves of artists at this point so it's hardly one generation anymore, but the term has stuck. animation like an artistic movement and its distinct digital stylizations, its relationship with working practices is the one baked into the term itself—it refers to artists scouted across the web rather than traditionally hired and trained, after all.

That process started with visionaries like the late Osamu Kobayashi cherrypicking young talent from different scenes, and very importantly, ensuring those were then guided by excellent veterans with sturdy fundamentals. After several webgenWebgen (web系): Popular term to refer to the mostly young digital animators that have been joining the professional anime industry as of late; their most notable artists started off gaining attention through gifs and fanmade animations online, hence web generation. It encompasses various waves of artists at this point so it's hardly one generation anymore, but the term has stuck. waves led by people who are now industry titans in their own right, that process has deteriorated so much that you can no longer consider it a distinct movement. Skipping all the introductory phases to work as a key animator or layout artist is no longer an exception supervised by veterans who will follow up with proper guidance, but rather an extremely common occurrence hastily brought by desperation at studios. And for every case where it works out well, many more lead to problems for all parties.

In an environment where meaningful training can’t be taken for granted even for artists joining studios through traditional paths—due to a lack of time, willingness, and simple respect for those supposedly lower-ranking jobs—newcomers scouted online must figure out nearly everything on their own, rely on small online communities with people who’ve suffered through the same paths, or simply fail. If that prospect wasn’t too much on its own, you can add the fact that a whole lot of people in that situation are also very young overseas artists, struggling with language barriers and physical distance on top of it. And to make things even worse, the consequences of those struggles extend to already overworked veteran enshutsu and animation directors, who are the main reason seasonal anime barely manages to air week to week. While their bitter, personal criticisms constantly thrown around as a consequence are easy to understand, it doesn’t strike me as particularly fair to push the blame on youngsters who’ve been recruited for a job no one actually trained them for.

Again, anime doesn’t operate according to universal animation truths, but rather insider practices that are not being passed down properly. In an interconnected world that platforms any youngster with a tablet so that they can be scouted for anime, but that doesn’t ensure they undergo any apprenticeship, how are these people supposed to be mindful of the placement of in-betweens—a job they never did? Even if they’re lucky to have undergone that process, can you be sure it was instructive, given that this intersection between overproduction and convenient tech encourages practices like copypasting the lines drawn by a more experienced artist rather than conscious, didactic tracing? Can you even take it for granted that they’ll eventually learn all these quirks, given how much work is remote and detached, with corrections not necessarily reaching the same person? That is the current labor paradigm in anime, and no handy innovation on its own will solve any of these issues without a fundamental change in the model; if anything, as we’re seeing, those convenient changes are flipped to tighten the noose some more.

To better understand the situation, both the gravity and how widespread the impact of this negative synergy is, it’s worth going through more specific examples. We started the piece with Ishihara lamenting the loss of hand-drawn trains, but when it comes to technological advances eroding anime’s traditional expression, that relates to a historically controversial change: the gradual disappearance of mechanical 2D animation. Specialized animation is by definition more susceptible to fade away from that pool of shared knowledge, and given its massive decline, few cases have been felt as strongly as this one. Although there are clearly other factors at play here, like mecha anime becoming less prevalent for starters, it’s once again that combination of lacking mentorship and a convenient alternative that has led to a loss of traditional technique.

As Gundam’s series producer Naohiro Ogata has noted multiple times, especially when he has to justify his studio’s decision to opt for 3D mechs, it’s a shortage of trained in-betweeners that gets in the way of more traditional robot productions. While enough specialized veterans have stuck around and could be in leading roles, all these years opting for the less cumbersome—which doesn’t necessarily mean cheaper, easy, or even bad—CG alternative means that it has become near-impossible to build an entire team to support such a production. With barely any in-betweeners acquainted with the specificities of 2D mecha animation, often demanding to juggle both perfect volumetry and natural movement, you either sacrifice quality or opt for a 3D alternative; something that even super high-profile Sunrise titles do on occasion now. The resulting work can at its best have an upside unique to its craft, but its expression is inherently different. And when that happens across an entire industry, that’s one flavor you irreparably lose.

While this is the most notable case, there are other types of specialized animation that are being genuinely lost to a more manageable alternative; one that again evokes different feelings, and given the dodgy nature of your average 3D cut in anime, realistically isn’t great for starters. If you watched the anime industry-themed hit Shirobako nearly a decade ago, you might recall that an arc revolved around the necessity to seek a great veteran animator to draw horses by hand. That conflict alluded to the increasing inability to animate animals and other creatures in traditional fashion, for very similar reasons as the whole mecha kerfuffle. By not passing down these specific skills to younger generations, means of expression are already being lost, as veterans like Ishihara worry about.

Looking at this issue solely from the angle of specialized animation, though, would miss the more fundamental erosion of skillsets across the industry. Throughout this entire piece we’ve already noted multiple lacking areas or bad habits that can be traced back to that combination of lacking training and overreliance on handy tech, and there are so many more to note. For an example voiced by a particularly notable figure, you can look at Mitsuo Iso’s rant against the now common preemptive abuse of keyframes. Without inculcation of the basics of timing, animation economy, and the simple awareness that someone else will have to clean up that mess, it’s natural for untrained youngsters to lean in that direction—something that Iso acknowledges, but also strongly warns against if you don’t have a solid grasp of the fundamentals. Coming from a living legend who precisely pioneered his full-limited approach that emphasizes the importance of keyframes to the max, that warning carries a lot of weight.

Iso is hardly the only veteran to point the finger at issues like that, and despite his bluntness at points, not the harshest either. If you follow industry folks on social media, you’ll be aware that it’s an increasingly bitter environment, with less than amiable complaints about newbie errors becoming more common by the day. For as deserved as some of that frustration is, I’d rather not emphasize the punching down too much—but at the same time, it’s some of the brutally honest complaints that shed the most light onto these issues. One of the most noteworthy recent rants on that note came from Mizue Ogawa, a super veteran from an animator household who jokingly declared that it had finally happened: animators are no longer a collective of people who can draw, as someone had straight up told her that they couldn’t draw a layout because they had gotten no 3D guidelines.

In our previous piece about the decline of anime’s layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists. and immersive quality, we noted that this was happening in spite of the industry relying increasingly more on 3D layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists. as the basis. What many other vets argue in her replies, though, is that this is in many ways happening because of that reliance, rather than in spite of it; with the implication being that it’s not the helpful tool on its own, but the abuse in an environment where the fundamentals aren’t drilled onto newcomers.

Kyouko Kotani, another veteran animator who is quite vocal about her complaints, has been consistently pointing out these particular issues too. In addition to the loss of traditional 2D fundamentals, she has pointed out that she will often come across unusable 3D layouts as well, explaining their failures in interpretation and expression. As another loud voice of agony in the industry has noted, the convenient assetization of background art elements will also often destroy the intended perspective and feel of shots, even when those had been carefully laid out in their drafts. At the end of the day, and regardless of how much your toolset tries to make the job easier, you need the same understanding of perspective and image composition to judge—whether it’s your work as an animator or if you’re the episode director checking it—if the cut is up to par. And that’s the type of knowledge anime is failing to cultivate.

Art does not need to stick to realistic perspective to be compelling, and there are endless valid approaches to animation outside the practices of the commercial anime industry. When working within these boundaries, though, there is a required common language that is being lost one word at a time, and a need to understand the fundamental rules even if your artistic intent in the end is to pointedly break them. There is a lot of fresh worldwide talent flowing into anime at the moment, but the failure to properly channel their energy through rigorous mentorship can make even that positive trend backfire tremendously. It’s no secret that viewers gravitate towards artists known for their eye-catching styles, but right now it’s the collective of less visible veteran directors and supervisors who through their overwork manage to turn that situation around to piece together something that can be broadcast every week; or, as has been happening a lot lately, most weeks until an indefinite delay.

Perhaps the scariest part is that the current environment doesn’t favor the growth of more figures like that. Instances of younger creatives who almost instinctively grasp the fundamentals and trickery needed to keep the anime machine going do exist, but between the counterintuitive nature that knowledge often has and this destructive feedback loop between insufficient training and overreliance on tech crutches, anime is not replenishing its capable leaders fast enough. That is worrying for the present, but even more so for the future, as ideas like the automatization of the in-betweening process continue to make noise.

Many of the arguments we’ve presented today as already absorbed realities already used to be invoked as potential what-ifs in a future where the industry completely ditched manual in-betweening in favor of interpolation and other mechanisms to generate them through software, some of them already partially in place at various studios. The desire to explore directions like this is understandable: in-betweening has been an unlivable job for many years, hence why so much of it is done on the cheap offshores, so why not get rid of the job as it is? For as tempting as that may sound if you don’t think about it too much, all the same issues we’ve been bringing up would become a magnitude worse. All youngsters would have to pick up absolutely all fundamentals on their own, as we’ve already seen that the training once you reach the key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. stage is insignificant. Given that these interpolation methods still require human supervision to get a passable result, you’d also need a steady influx of veteran checkers… for a job that wouldn’t naturally produce them, as it wouldn’t really exist anymore.

In the end, it’s hard to see a way out of this without an industry-wide change to the production model. It’s an environment so poisonous that even positive changes on paper materialize in all sorts of harmful ways, and frankly, the problem in people’s hands is so complex that the final read on the current situation depends on how you feel about each of these moving parts. Personally, I do not see the technological advances that have been introduced so far as inherently negative, but it’s worth noting that some very notable people are landing closer to a harsher conclusion. Legend among legends Masao Maruyama recently argued against building around efficient technology as the be-all-end-all in animation, then going as far as arguing that Japanese animation has already collapsed; in Maruyama’s view, it lost its unique charm in the digital transition, and was never able to explore new equivalents as studios no longer properly train creators in all these areas we’ve gone over.

Perhaps a bit naively, I still believe that with a deep reform of the employment, training, and production systems, anime could rebuild around the helpful digital tools of the present. But through hearing all the first-person experiences of acquaintances deep in the maze anime has built for newcomers, and reading up on so many bitter veteran complaints, I’ve become deeply aware of the damage even a seemingly helpful tool can accidentally do in the long run. It’s easy to buy into those ideas of convenience and efficiency, but looking at the consequences, you simply have to ask yourself: who has all of this being convenient for? That’s the paradigm that must change.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

Well i did not know about the Ishihara interview, while not a fan of his style its nice to know his stance on AI more so because he cannot draw (not trying to be rude at all) and how he laments over lack of 2D drawings that has now been replaced by 3DCG, while trying to optimistic i hope KyoAni remains one of studios that values hand drawn animation even after seeing how 3DCG is more visible in their recent works and after reading that interview deep down i still fear that loss of a veteran like Kigami who was… Read more »

This was a fantastic read and extremely insightful about practices in the industry and questions I have had ( why don’t we get more of the extravagant mechanical movement so prevalent in 90s sci-fi flicks anymore? )

thank you for taking the time to write this

The timing of the posting of this article could not have been any more perfect.

how so?

Today on Twitter, people from Mappa were complaining so much about the hellish production behind Jujutsu Kaisen Season 2 that Mappa apparently put NDAs up to have people stop talking about it.

AI can leech off the work of past craftsman to create work that’s “good enough” for some group of people, but there’s no getting around the fact that automation cuts short the passing on of technique. The process of honing your craft can involve tedious and painful work at times, work that like in-betweening may seem to be a ideal candidate to eliminate, but it’s necessary to develop the skill that allows you to do actually interesting work. And that isn’t even getting to the problem you raise of increased technological efficency leading to increased demands on people to output… Read more »

“As another loud voice of agony in the industry has noted, the convenient assetization of background art elements will also often destroy the intended perspective and feel of shots, even when those had been carefully laid out in their drafts.” THIS. I often find that my eyes are drawn to the sterile, digitally assembled backgrounds common to modern anime, rather than the characters I’m supposed to be looking at. This issue particularly affects interior shots, where desks, chairs, books, curtains, etc. seem to be pulled from preexisting image libraries, rather than being designed for individual series. Outdoor scenes aren’t impacted… Read more »

Really, it’s only them, and maybe Bihou (particularly their more stylized efforts like Eizouken), Easter and Totonyan who I can say the backgrounds actually look decent to great. But if we’re being honest, all of them are just as guilty of cheapening out on background art as much as the more serial offenders like Tulip, Kusanagi or Production ai are.

At this point, it really feels like the anime industry just needs to cut down. There are more and more projects coming up and animators spread between them. Take some time to figure out better scheduling instead of taking jobs right away (I hope that’s feasible).

You would think that, and you’d be right. The problem in that case though are the people funding these projects. Companies like Kadokawa, Netflix, Aniplex and TV Tokyo are either ignorant, uncaring or unwilling about any of this situation going on behind the scenes of the anime titles they commission because of THEIR bottom line (it’s why you also got the WGA strike that happened recently, or people opening up about how VFX companies like MPC are as bad, if not worse, than MAPPA in terms of working conditions). Their greenlighting of over 50 titles a season is part of… Read more »

Speaking of the disappearance of 2D trains, remember when 2D cars were the norm? Now you see 3D cars much more often, and it’s been that way for such a long time now. 2D cars could basically disappear altogether too.

They’re definitely on their way out too, for all the reasons mentioned, but also due to some societal changes – which is to say, cars being less central to people’s lives. Here’s a fun anecdote in this regard: an episode of Tsurune S2 had the characters riding a car to the hospital, which they did animate traditionally. However, the people in the episode’s compositing team happened to be pretty young non-drivers, so at some point a veteran had to step in and explain that headlights at night get nowhere as bright as they had depicted them, because if they did… Read more »

have been watching martian successor nadesico lately and was struck by how the scenes calling back to 1960s toei super robot anime are just perfect replications, and feel like this put into perspective that of course they are – the people who were animating nadesico were trained by those animators! the techniques had been passed down directly. now when a modern anime tries to replicate a 1990s anime it never reaches that kind of authenticity and its not just because of the switch from cels to digital, the actual techniques to animating like that are lost.

We all know that the use of AI it has its only purpose. Money. In my opinion, the future of anime will be in the hands of mangakás, artists who are part of the #indie_anime movement and of course, those against AI. If mangakás don’t wanna see their story to fall apart and be a shame through the ”hands” of AI, they’ll stand up for their work. I’m saying this being an artist myself. We artists want people to recognize something through our work. Some, want to show their effort and dedication. Some want you to know that they like… Read more »

I was well aware of Animators conditions in the industry but I was not aware of the technology advancements and their implications in the industry and the over all dark side of Anime industry. I really pray and hope that industry will start to do something about it. I have even more respect for animators. I hope they will get better training , treatment and pay that they deserve.