Studio Ghibli’s Overlooked Training Project: 25 Years Since Ocean Waves

Back in May of 1993, Japanese audiences got to experience a curious experiment: studio Ghibli’s first and essentially last large-scale TV project, a film meant to put their younger staff under the spotlight for a change. Let’s look back at a fascinating little chapter in their story, since both its achievements and shortcomings are rarely discussed with the full context in mind.

Ocean Waves really is a curious case – starting by the fact that you might instead know it by the more literal translation of its Japanese title I Can Hear the Sea, as Ghibli neglected the movie and didn’t grant it their usual official localized name for a long time. Considering how much attention almost all works by the studio receive, the existence of some fairly obscure exceptions gives those a special mystique that might lead you to believe they’re forgotten masterpieces… which as far as I’m concerned this one really is not, as fond of it as I am. At the same time, claims that it was thoroughly mediocre undersell it, and the common interpretation that it was a failure because it didn’t succeed in raising a new generation of Ghibli creators as intended is pretty ahistorical and ignorant of the context. This month marked 25 years since its original broadcast, which gives us a nice opportunity to check what this equal parts interesting and messy little project was like.

To understand where Ocean Waves came from, we’ve got to look back a bit further than that. As documented in The Birth of Studio Ghibli, after wrapping up the production of Kiki’s Delivery Service the studio was forced to tackle a conflict we summed up in our Takahata retrospective; the reliance on freelancers and poor remuneration considering the immense effort that went into their films compromised Miyazaki and Takahata’s ideals, since they once famously fought for worker rights. They stayed true to their beliefs and took the risky bet of entirely restructuring the way the studio operated, switching to a salary system and making an effort to raise talent of their own. Those youngsters were trained in Takahata’s Only Yesterday and Miyazaki’s Porco Rosso, but they needed a platform to stand on their own – and the stars aligned for that idea to become Ocean Waves, which not by coincidence was the very first project animated at their now iconic, idyllic studio. A true fresh start!

This is worth pointing out because the project’s intent to give young staff an opportunity is often conflated with Ghibli’s unsuccessful attempt to find new directors to handle their works, an attitude that’s reductive at the best of times. Don’t get me wrong: that was a factor as well, and as you likely know, they didn’t succeed at all. Much like other renowned directors like Mamoru Hosoda and Hiromasa Yonebayashi, Tomomi Mochizuki failed to become the successor to the titans who founded the studio. Neither raw talent nor sharing artistic (or even literal!) bloodlines could achieve something that was essentially impossible by design – offering something new while at the same time following up the exact steps of the biggest figures in anime. In the end I would argue that Ghibli’s brand asphyxiated even Takahata, whose works were heavily penalized in the box office by his desire to stray away from their established identity, so I wouldn’t blame anyone for failing to sit on a throne that had become Hayao Miyazaki’s alone.

This isn’t to say Mochizuki’s work was without fault, of course. The movie is admittedly clumsy, starting from the patchwork narrative framing device that struggled to cover both past and present even after a sizable length increase. The management of the project in general didn’t fare much better; what was intended as a cheaper, quick TV project ended up costing well beyond expectations, and for all their intent to give Ghibli’s own youth the main role, they had to rely on other studios to save the production from doom. The stress piled up to the point that Mochizuki himself passed out, while he tried juggle his responsibilities with other productions he’d accepted beforehand. But the fact that he enjoys reminiscing about the project, including detailed retellings of the incident that sent him to the hospital, proves it was in its own way a worthwhile experience. Quite the thematically appropriate point of view too, as fans of the films might have already noticed.

As a final note before tackling the film itself, you might be wondering exactly why this was a TV anime. Ghibli is all about movies after all, and even the exceptions that aren’t theatrical projects tend to escape television (the first iteration of Ghiblies, a smaller scale effort, being the other notable exception). The reason is simple: NTV. The network wanted something special to celebrate their 40th anniversary, and so their needs aligned with those of one of their best allies, the hit anime studio they had helped so many times. NTV has been in the committee of all their movies, something that wouldn’t have been possible without the very personal bond that tied their producer Seiji Okuda with Ghibli’s core. His role in directly yet unintentionally inspiring multiple Ghibli movies is well-documented, as is the fact that he’s also the man behind Miyazaki’s naming pattern. Very few people have had as much of an impact in anime while staying relatively unknown, so his recent move to film distributor Shochiku could quietly be huge news… or a chance for him to finally take it easy. Only time will tell.

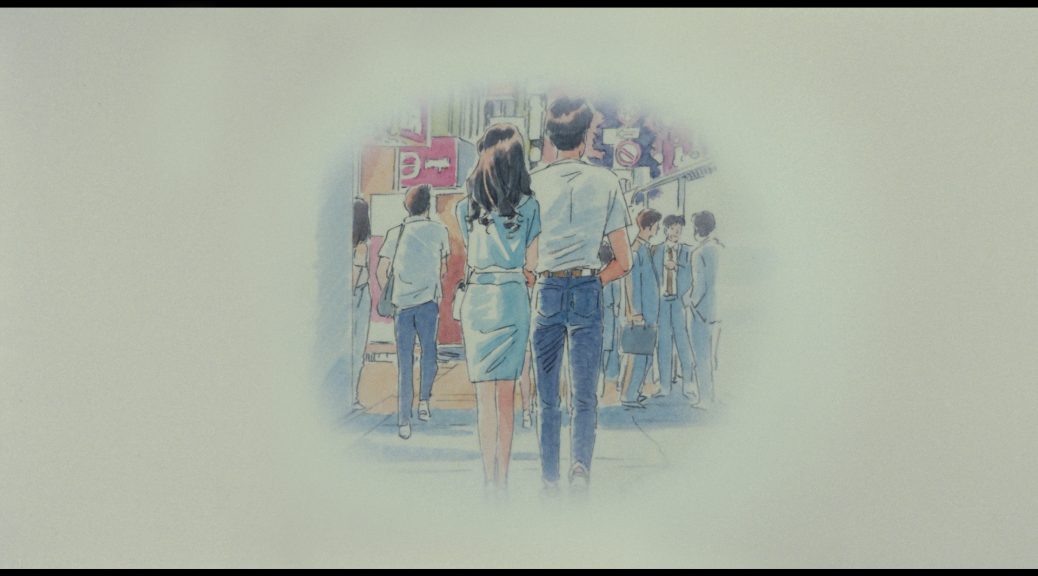

But let’s go back to the movie. Truth to be told, there isn’t much to this story: Ocean Waves is a nostalgic, kinda awkwardly told flashback that lets us see how two friends dealt with the arrival of a beautiful girl to their school, their troublesome experiences together and how they drifted apart. Back in the present, the movie outright states its thesis by explaining that the passage of time had expanded their worlds and that distance allowed them to appreciate just how much they enjoyed being together. Undeniably clumsy, but it’s a charming movie that earns its sweet ending. All of this is made much more interesting however once you remember that the production was mostly entrusted to up-and-coming creators, making it a tailor-made effort for a movie about growth.

Would the staff be able to look back on their hectic past with a smile, like the characters did? Director Mochizuki definitely does, hence why I’m not fond of the reading of this movie as his failure to become Ghibli’s new star. Sure he didn’t achieve that, but it was through projects like this that shine in their quieter moments that he developed his style; though his early work is often talked about for his quirky ideas when it comes to camerawork (best exemplified in this ridiculous Kimagure Orange Road sequence he storyboarded), over time Mochizuki began focusing on clinical control of the atmosphere, with a holistic vision that gets him to cover tasks as varied as writing and sound direction on top of all the standard directorial duties. Considering he was quite the fan of the source material to begin with, it’s no surprise that even his reckless decisions and the harsher experiences during the production left him a bit of a sweet aftertaste. In a way, the movie was set up as a self-fulfilling prophecy.

And it’s not just the director who found something that resonates with them in this tale, the experience extends to the team as a whole. Much like the characters, plenty of artists went through a graduation of sorts when producing Ocean Waves. People who would go on to become long-time Ghibli animators like Takeshi Inamura and Hideaki Yoshio got to draw key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. for the very first time in their careers. That also applies to Kenichi Konishi, a driving force not just at Ghibli but with Shin-Ei, but also under directors as accomplished as Satoshi Kon or Shingo Natsume. But before making history, this project allowed him to jump a couple of steps at the same time, since he was asked to do some uncredited corrections as assistant animation director too. The same could be said about Masashi Ando, whose most recent feat is of course Your Name’s thoroughly acted performance, as well as iconic character designer Kenichi Yoshida. All things considered, the animation is accomplished but hardly spectacular by the studio’s standards (with the exception of Mitsuo Iso’s sequences perhaps), but as a formative experience for artists who went on to become anime superstars, it was invaluable.

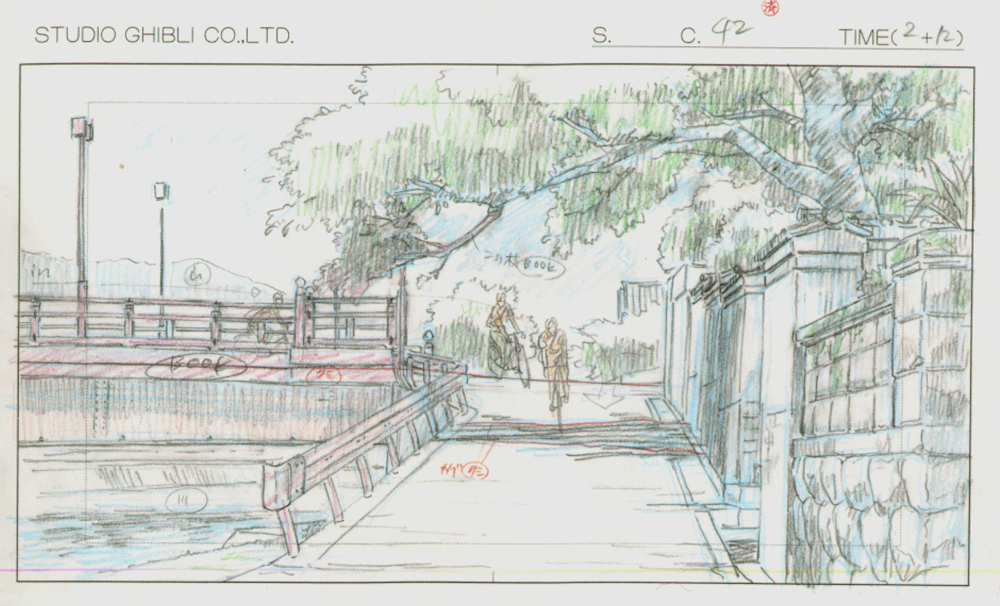

The movie’s background art comes across in similar fashion. Beautiful for sure, with the tint of nostalgia that permeates every element in this film, but at the same time an undeniable step down from Ghibli’s outrageous standards due to the responsibility being placed on newcomers. Ocean Waves’ world feels like a mix of Only Yesterday’s two registers, but it can’t compete in sheer detail nor evocativeness, and lacks the encompassing ethos Kazuo Oga gave it. As Naoya Tanaka’s very first work as art directorArt Director (美術監督, bijutsu kantoku): The person in charge of the background art for the series. They draw many artboards that once approved by the series director serve as reference for the backgrounds throughout the series. Coordination within the art department is a must – setting and color designers must work together to craft a coherent world. though, it’s hard to fault it much – which Ghibli definitely didn’t, since after this project he became one of their main art directors for a long time, right up to his departure to studio Polygon Pictures. The list of painters he commanded at the time included other youngsters who went on to accomplish big things as well; beyond all the Ghibli-affiliated ones I’d like to highlight Seiki Tamura, who trained with them on projects like that before joining Anime Kobo Basara and turning it into one of the most renowned art companies in the industry.

Would all these talented youngsters have moved up either way? The answer is that most likely yes, they’d have eventually found another project that would have let them step up their game. Ocean Waves simply happened to fit their exact needs at the right time, with a story that mirrored theirs to boot. No one’s career peaked here, and it’s understandable that it doesn’t have the massive following of other Ghibli titles. It was a messy tale of youth that served as the launching platform for a more brilliant future. But as the movie hypothesizes, looking back on it, there’s plenty of worth to that.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

Earlier today I saw that “Like The Clouds, Like The Wind” got an English BD release. I seem to recall that movie also had some younger (ex-)Ghibli staff involved. How does it compare to Ocean Waves?

It did because of Katsuya Kondo’s position as designer and animation director, I believe. It’s been a while since I watched it but I recall it being a stronger animation effort that in the end didn’t leave as much of a lasting impression as this kinda messy TV movie.

Nice write up. I didn’t know the director passed out working on this, even simple anime are rip currents under calm water.

Ocean Waves had sweet moments, some I’ll never forget, like the two friends reminiscing by the water or staring up at the lit temple and seeing the beauty, though, he once thought it a waste of money.

Well, I might be digging this out a year and a half after publication, but what can I do, between the Kimagure movie two Tuesdays ago and this one earlier today, I’m having a very good ride with Mochozuki lately (god I gotta rewatch Twilight Q). I feel that this movie wasn’t sloppy, rather very heavy on the realism. Two dumbassstic dumbass teenage dumbasses will propably make for a mess of a tale of young love, can’t blame the premise nor the execution. I like how after the Kimagure movie’s very impactful and aggressive shot composition this one is much,… Read more »