The Pre-Production of Anime #2: Scripting

Welcome back to megax‘s series “The Pre-Production of Anime”, following the journey anime goes through before coming to fruition. On the first post we mentioned how the initial pitch is used to gather the necessary funds and creators, so now it’s time to actually begin the creative process. How is anime written?

Part 2: Scripting

As we mentioned last time, each project has its own production proposal: a document created to sell the idea to other staff members and producers. This typically contains the general outline of the story, but their level of thoroughness varies rather heavily; you might have a very detailed, actually structured rough narrative that already goes in-depth about the main characters, as well as a more businessman-like approach mentioning a general concept with vague ideas to try to capitalize on. This isn’t necessarily definitive either, as there’s many examples of storylines that changed dramatically from the pitch like Free!.

If you want to know just how much an anime can depart from its original idea, let’s look back at Hanasaku Iroha. It started out as an “action girl” show because P.A.Works’ CEO Kenji Horikawa and Infinite’s Takayuki Nagatani felt it was a natural progression from CANAAN, and thus they hired Masahiro Ando as director due to his action expertise. While the studio finished work on Angel Beats, they realized they didn’t want to make that kind of show anymore, so they changed the general concept to a show about “working” featuring high school girls. They hired someone used to writing such tales like Mari Okada as series composer, and then let Ando direct it anyway – which he happily accepted claiming that it let him try out something new. Don’t assume that all decisions by higher-ups run against the will of the creators! A more minor but still substantial change happened with Flip Flappers. Originally it was supposed to be a space opera featuring 2 girls, but after working on Space Dandy, the staff had it evolve to go to different dimensions instead of different parts of the galaxy.

Once a production has been greenlit and the main staff start to come on board, the next major step is to plan out the scope of the series and how to distribute the content amongst the episodes. If we’re dealing with an adaptation of a novel or manga, then it’s likely that the producers have an idea of where to end the series; as you will no doubt have noticed if you’ve seen many of those, if there’s no self-contained tale they tend to deem cliffhangers that leave you hungry for more as a good stopping point – not always the most satisfying thing as a viewer, to be honest! In case the publisher knows that the author will be finishing the story soon, it’s possible that they begin to collaborate with the anime staff so that both the adaptation and source material finish around the same time. One of the best known examples of this involved Ascii Media Works and the Genco-produced Toradora anime, which adapted all 10 novels (plus one tale from a short story collection) in 25 episodes, finishing 3 weeks after the last novel was published. Another good example would be Ichiro Sasaki, who trusted studio BONES twice so that they could fully animate Scrapped Princess and Chaika, even before the final novel was published in the latter’s case. Now that’s some genuine faith in the staff.

Fans often speculate that unreasonably rushed pacing in anime is due to “(company) promising more episodes and then cutting the amount.” That’s rarely ever the case, though there are some notable exceptions. Fuji TV and Aniplex’s producers had originally planned Galilei Donna as a 2 cour production, but it was scaled down by Aniplex to a single cour for reasons that have never been detailed. It’s easy to speculate about other instances, but Galilei Donna represents a rare instance where the creators have confirmed those issues. That forced them to squeeze their content into 11 episodes and as such the production suffered. Conversely, we know of an example where the director and series composer tackled too much for 12 episodes and begged the producers for an extra one: Full Metal Panic! The Second Raid. This is all to say that almost in every case, an anime that feels rushed is due to questionable decisions taken by the series composer and director during pre-production, whether because they genuinely believe in them or due to pressure by the execs. This doesn’t always become public knowledge of course, since those are decisions the producers don’t really want the audience to know. In cases like Kunihiko Ikuhara’s original anime Penguindrum, it seems clear that the original draft included more ideas and characters to be explored through extra episodes that were cut at some point, and so the final product unnaturally dropped entire arcs it hinted at.

How does a story get divided into episodes, then? Though it’s a bit of a cliche, the right phrase to use is “it’s an art.” Most TV anime follow very standard narrative structures. They attempt to introduce us to the characters, get us to care about why they’re doing something, introduce conflict/uneasiness, and resolve everything at the end. Fan concepts like the 3-episode rule only exist because that’s often how much it takes for substantial introductions, though it’s true that producers sometimes push for relatively self-contained 2/3 episodes chunks to coincide with the Japanese disc releases. Broadly restructuring the series is sometimes necessary, to improve the flow and as an attempt to hook viewers early on and make them pay attention to your show over the dozens upon dozens of alternatives. Even many of the people who have come to despise Sword Art Online were quite impressed by its first episode and the palpable tension when it introduced the conflict, which was one of the many changes director Ito prepared to better organize the material he was given.

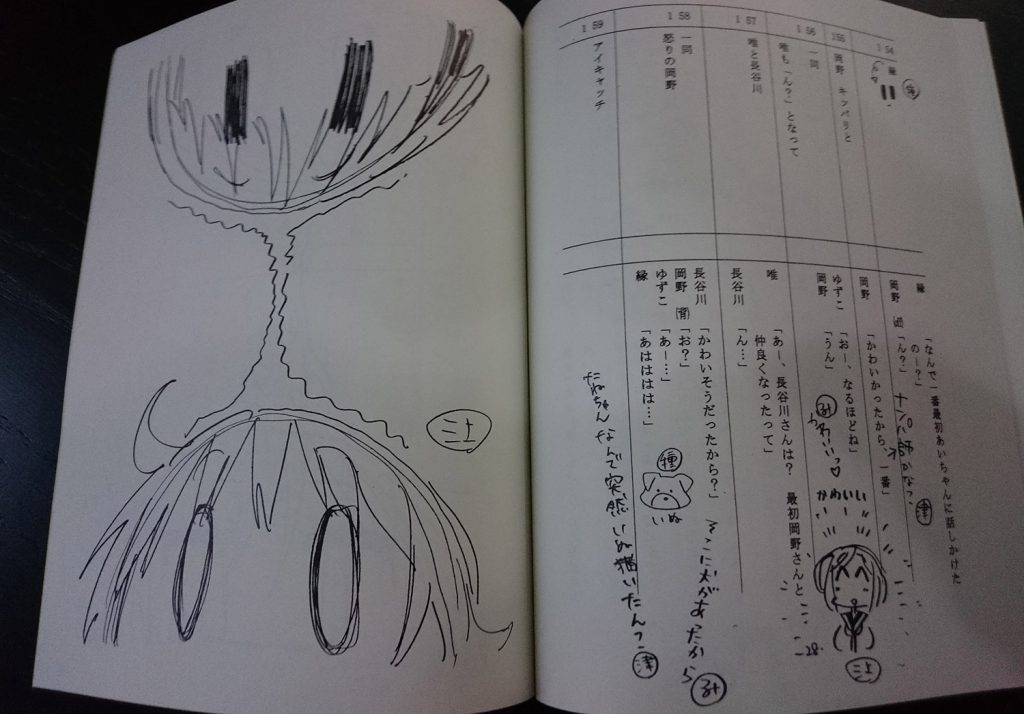

Once the main storylines are completed, the series composer hands the scriptwriting duties off to the writers for each episode. The scriptwriter takes the main points for that episode (and the content from the source material if present) and then writes the exact actions and dialogue that would take place in the ~20 minutes of content they’re entrusted with. Some composers want to handle each episode themselves like Jukki Hanada, while others focus on main episodes and ask others to write the rest. Sometimes, busy enough schedules might even cause the series composer to seemingly disappear after writing a couple of episodes early on. Regardless, it’s the job of the individual scriptwriters to expand on the main points already decided by the main staff; there is a creative component here of course, but it’s not the free writing credit that some fans assume.

To be more precise, let’s focus on another concrete example. There was a lot of discussion regarding Flip Flappers a while back, since its relatively rushed production caused the person in charge of the story concept to “leave” after handling the scripts for the first half. Thus, the second half was instead in the hands of a writer associated with Infinite, one of the companies involved with the project. It didn’t change the concept for the series as that had already been decided beforehand, but it meant that elements like dialogue would be slightly different in tone as someone else handled that aspect. The series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario. Kiyotaka Oshiyama himself acknowledged that both writers left a personal imprint in the series, but that didn’t mean that scriptwriting for the second half changing hands entailed any narrative changes; after all, unless you’re dealing with an experimental anthology project, the role only consists of developing already established ideas into a 24 minutes chunk.

While the director and series composer handle the overall direction of the story and oversee the scripts themselves, they’re not the only ones who have input in that regard. Producers may request certain aspects be included as well. A merchandise company can push for additional focus on certain characters because want the audience to care about them, enabling further monetization. One producer for Tamako Market requested additional scenes at school in order to have more focus on the teenage girls, in contrast to the older, less marketable (get it?) characters in the shopping market. In the end those barely existed, so in this case the creative side managed to hold their ground. Finally, the last role we have to mention regarding scriptwriting is “literature.” Though the exact details change between productions, this person is in charge of obtaining the scripts by their deadlines and passing them onto the episode directors/storyboarders to advance production onward. They may also sit in on readthroughs of each script/revision sessions with series composer and directors and provide their opinion on bits or things to change, plus general small tasks involving right about everything that can be considered writing work.

To summarize, there are a lot of people who work on the scripts for a show. While the director and series composer create the basis for each script, the producers, additional scriptwriters, and even the literature staffers are all involved in forming the final version of the script…which might then be altered by the episode director/storyboarder, if they deem it necessary. It’s all a collaborative effort, so everyone gets the credit and/or blame for aspects that may not be favorable to viewers. Trying to blame someone like Mari Okada for one aspect rather than a director who may have wanted it or a producer who suggested writing that ignores how much they all work together for a script. It’s all a team effort.

While the scripts are being worked on, another batch of people are working towards the designs of the various parts of production; this includes characters, backgrounds/settings, and even the props that are used. We’ll never get tired of pointing out that anime production involves many endeavors happening at the same time, so it’s not as if those wait until a show has been fully written. But for now this is all, we’ll touch on those matters next time!

Support us on Patreon for more analysis, translations, staff insight and industry news, and so that we can keep affording the increasing costs of this adventure. Thanks to everyone who’s allowed us to keep on expanding the site’s scope!

Oh, I thought the Flip Flappers case was planned beforehand, does that mean that animating the episodes uncronologically (?) wasn’t intended either? And why does the scriptwriter seem to make or break a show at times? I mean, if they are only core ideas written, why was it feared that, say, Shuumatsu no Izetta’s writer would handle the series composition? Does he decide things like whether a show will be rushed or not, keypoints and so much the ideas behind the show?

I didn’t follow much of the discussion on Izetta (other than helping a friend with a piece he wrote before the show debuted), so may I first ask: what exactly were people saying about Yoshino?

The paragraph talking about Izetta’s scriptwriter. https://blog.sakugabooru.com/2016/09/26/fall-anime-2016-preview/

Hm…Kevin will have to answer that, as I can’t tell why he was so pessimistic about Yoshino from what he said there.

I mean, I know what I find frustrating that I can definitely attribute to Yoshino (a certain trope that showed up in Code Geass, Mai-HiME and Macross Frontier), but I’m probably as curious as you are about what other people don’t like about his work–or what they attribute to him, anyway.

I think Yoshino is genuinely the worst high profile scriptwriter in the industry so I’m glad we got over the period where he got every big project, with Aniplex in particular dropping him in particular. Part of my dislike comes from purely technical aspects – I think he has 0 series composition sense, and his delivery of even individual scripts is awkward. And besides that, as a writer he embodies all the creepy tropes that put me off from early 00s original Bandai crap. Really not a fan.

I will never not be salty about Galilei Donna’s halved length.

Could you name some of the ideas/characters/arcs that were dropped from Penguindrum? I can’t remember any.

I think Mario is the most blatant “there’s supposed to be an arc here but you won’t see it” example. Yurikuma obviously had ideas for a longer run but Penguindrum actually brings some up and then just moves on. Love my flawed masterpiece.

I FORGOT MARIO EXISTED

So did the show, tbh.