The Pre-Production of Anime #3: Design Work

Welcome back to The Pre-Production of Anime, Megax‘s series following the path of an anime production from the inception of the project until it’s ready to be animated. Last time we talked about how a production organizes its writing work, so today it’s finally time to examine the design process and the main roles it entails. Let’s get to it!

Part 3: Design Work

Character Designs

The production proposal we talked about in previous entries tends to include visual depictions of the main cast, even if they’re just drafts subject to change – the rough equivalent of early visual development process in the West. If we’re dealing with an adaptation of a manga or light novel then the original designs can serve as placeholders, but otherwise the proposal might feature very basic depictions, sometimes even just vague written descriptions of their appearance and character.

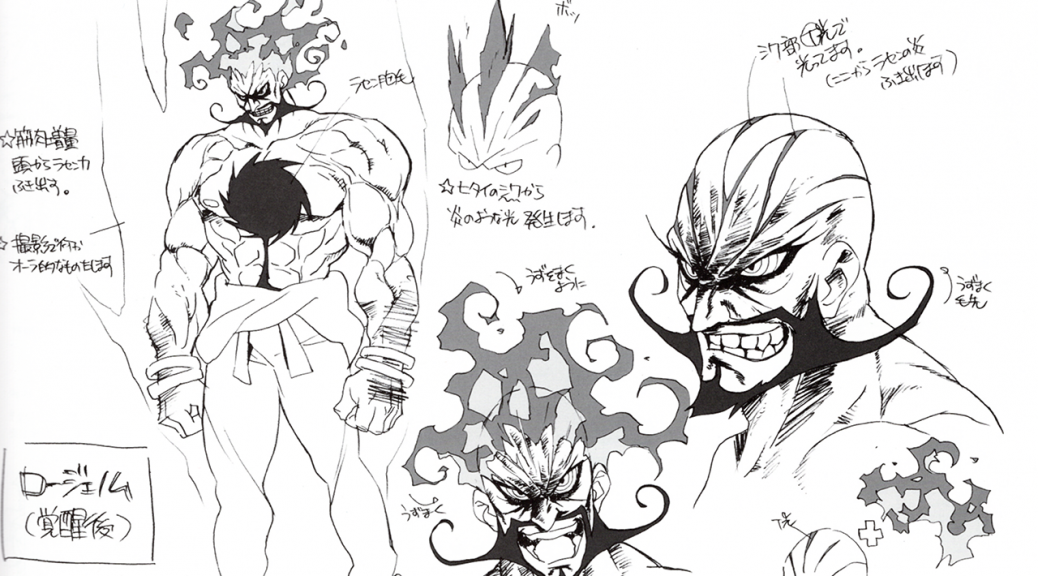

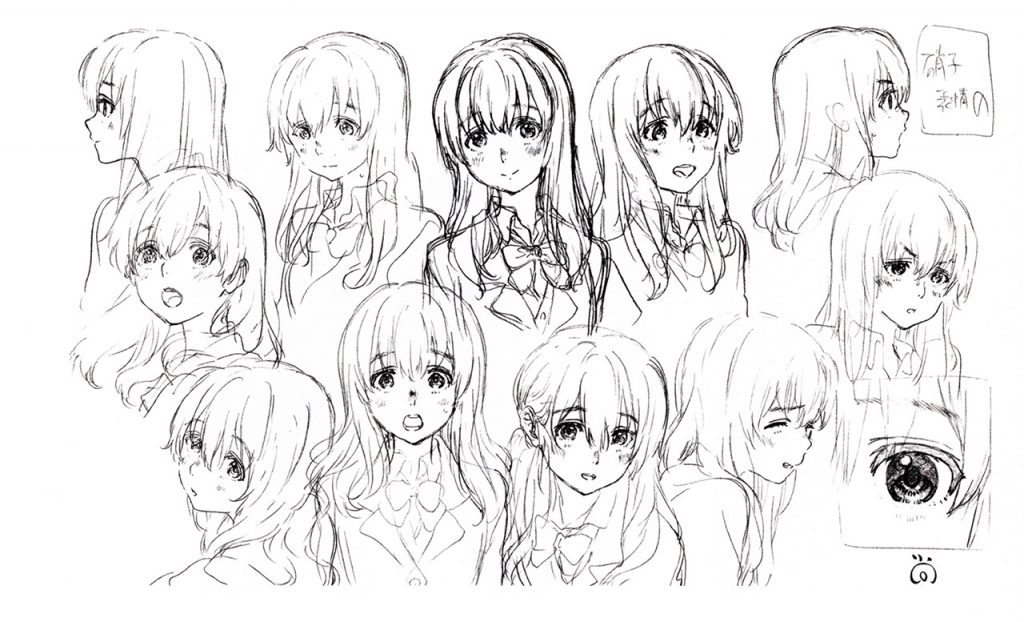

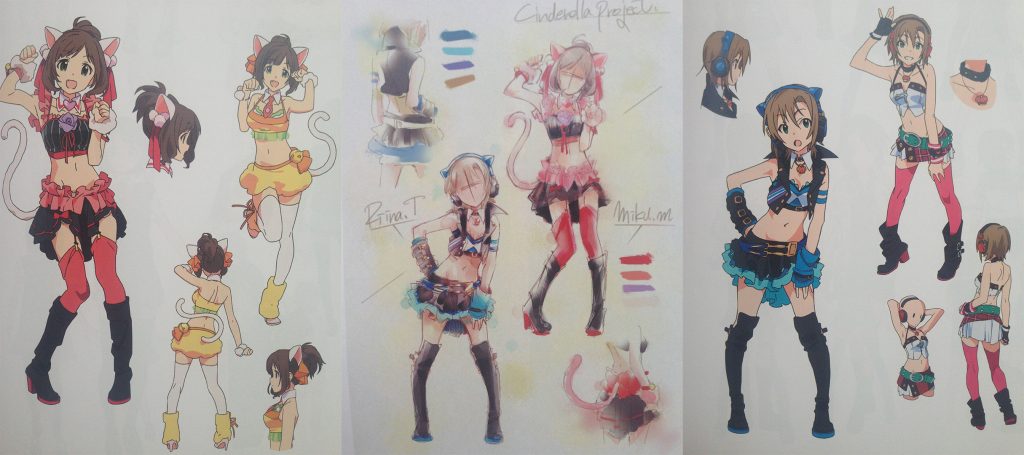

Following that proposal, each character has to be (re-)designed in order to be drawn by animators. This isn’t the same process as designing a character for manga or illustration purposes; these designs need to be created so that animators can easily replicate them from different camera angles, and more importantly, be fit for movement. Characters are perceived as a whole, but creatures don’t move as blocks, so the designs have to be mindful of every one of their parts, and gear their drawings towards ease of motion. This tends to mean that they have to be economic with their level of detail (unless they’re monster designers/supervisors like Futoshi Nishiya), but assuming that just by making drawings simple you’ll achieve the best animation designs is a mistake; if your references don’t make it clear how the designs should operate under different circumstances, no level of stylization will save you.

There are different degrees of design authorship depending on the project. For adaptations of visual media, the designs will likely be adapted using the source material as a basis. If we’re talking about original anime, then the animation character designers may create them from scratch. However, famous illustrators are also chosen to draw original designs (more often seen on original projects, but even adaptations can follow this route) that will later be adapted into animation character designs. This last method is often recommended by producers as a method to generate interest amongst fans as we detailed in the anime planning piece, but we’ve also seen creators willingly following this path.

Productions with source material often have the original designer send over reference images for the animation character designer to use when adapting the cast. Sometimes the anime staff may request additional designs, such as new clothing variations for the characters, but generally that’s handled on the anime staff side since the original artist is under no obligation to conduct extra work. One high profile exception involved abec/bunbun, the original illustrator for the Sword Art Online novel series, who created multiple variations of the clothing used in the series as well as new minor characters, plus additional races for the second arc in the series. The animation staff were incredibly grateful for the work he put in for that adaptation, as it’s far beyond what is typically expected from the illustrator.

The process doesn’t actually finish after wrapping up the main cast. Recurring minor characters may be handled by sub-character designers, especially when dealing with massive casts. And if an episode needs one-off characters that there were no reference sheets for, those might be drawn by the animation director for that episode or another trustworthy animator involved in the episode. These have to be checked by the main character designer and director before approval…if time allows, that is.

Background Designs/Art Design

Once the main staff and/or the committee members decide on an art directorArt Director (美術監督, bijutsu kantoku): The person in charge of the background art for the series. They draw many artboards that once approved by the series director serve as reference for the backgrounds throughout the series. Coordination within the art department is a must – setting and color designers must work together to craft a coherent world. for a production, it’s up to them to realize the director’s vision into the fully-fledged scenery that they will use for that work. Due to a variety of circumstances, they tend to have quite a lot of leeway in this role; directors generally don’t specialize in this field, standard source material for anime isn’t usually very thorough at depicting their worlds, and original works understandably leave them even more room to do their thing. Either way, their goal is to craft surroundings that will feel believable in that world – not to be confused with realistic! If it is set in the real world, they will use certain locations for reference and design the world inside the work to mimic that area. And even if it isn’t, location hunting is common as long as the setting isn’t terribly outlandish.

Once the director conveys their goal for the backgrounds, the art directorArt Director (美術監督, bijutsu kantoku): The person in charge of the background art for the series. They draw many artboards that once approved by the series director serve as reference for the backgrounds throughout the series. Coordination within the art department is a must – setting and color designers must work together to craft a coherent world. (and designers if specifically designated) will begin planning the world design process. As most animation production studios lack an art department, these are typically chosen from companies that specialize in background artwork. Often it’s due to connections between animation producers and the director, but sometimes the studio is sought due to the their distinct style and skill – which explains why Studio Pablo is currently booked until the end of time.

There are as many ways to operate as there are projects, but generally this crew will create design documents called art boards (美術ボード) and art designs (美術設定/設定画), serving slightly different purposes. Art boards are sample drawings of particular areas and situations in the story to show the color usage and general tone of that moment. They are adjusted for special occasions such as time of day or special in-universe events like festivals. In contrast, art designs are always detailed drawings serving as the blueprint of the buildings or locations with a character inserted for size comparisons. Key animators need these to judge how their character will fit into the background when composing the layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists. for scenes. The background artists use these layoutsLayouts (レイアウト): The drawings where animation is actually born; they expand the usually simple visual ideas from the storyboard into the actual skeleton of animation, detailing both the work of the key animator and the background artists. along with the art boards for drawing the backgrounds for that specific scene. As usual though, I recommend to keep an open mind towards terminology and workflows; when you’re producing something, those are secondary to actually achieving your goals, and everyone approaches the craft in their particular way. Always important to remember that!

One additional point worth noting the increase of 3DCG in backgrounds both in-show and and to serve as references. While this wasn’t uncommon, the frequency of this has notoriously increased in recent years as productions have increased usage of dynamic 3D camera movements. As such, these designs too have to be created and approved by the art staff and director, meaning they have to collaborate with the 3D crew if they don’t have artists who specialize in that. In the end, their work can also be used as reference to draw 2D backgrounds.

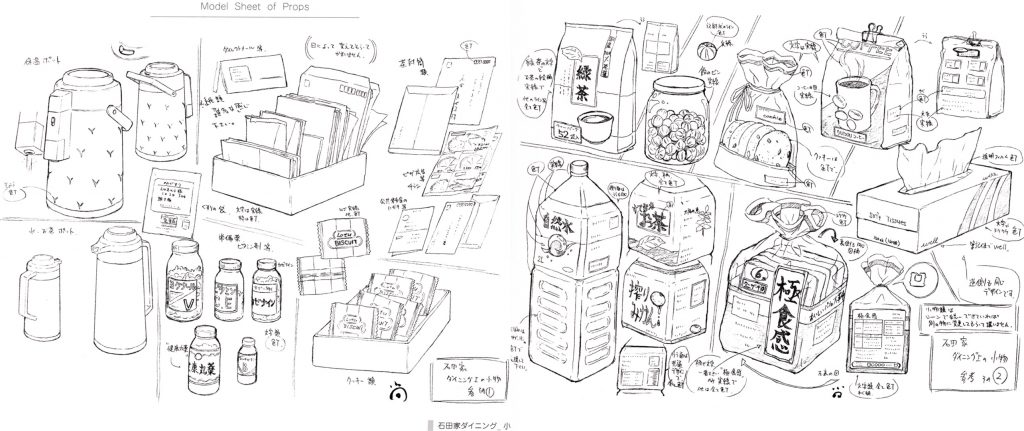

Prop/Accessory Designs

Animators don’t just draw the characters, they are also responsible for drawing the non-inert items in the world. If someone uses a cell phone, it has to be designed to match them and their setting without saying a single word. Is it a retro phone? Smart phone? What model? Is it adorned with any accessories? Similar trains of thought are followed for every element in the series – if no detail is put into it then you end up crafting a barren, artificial world, and without specific sheets then you’re at high risk of ending up with continuity errors. Major items that will be used each episode will need to be designed at the beginning of this process, while less important ones that may get used once or so can be designed during production for that particular episode.

If you’re told that each production requires different types of props altogether you’ll immediately think about drastic circumstances: obviously a war story will tend to seek artists specialized on weaponry to design and supervise the process, whereas the similar figure of a Creature Designer is common in fantasy works and also requires expertise. The truth is that even perfectly down to earth projects benefit from this attention to detail, though. To give one precise example, the staff for Hanasaku Iroha stayed in an actual ryoukan in the area and used their materials as the base for the ones used in the show itself. That’s the kind of dedication that elements you might never notice require!

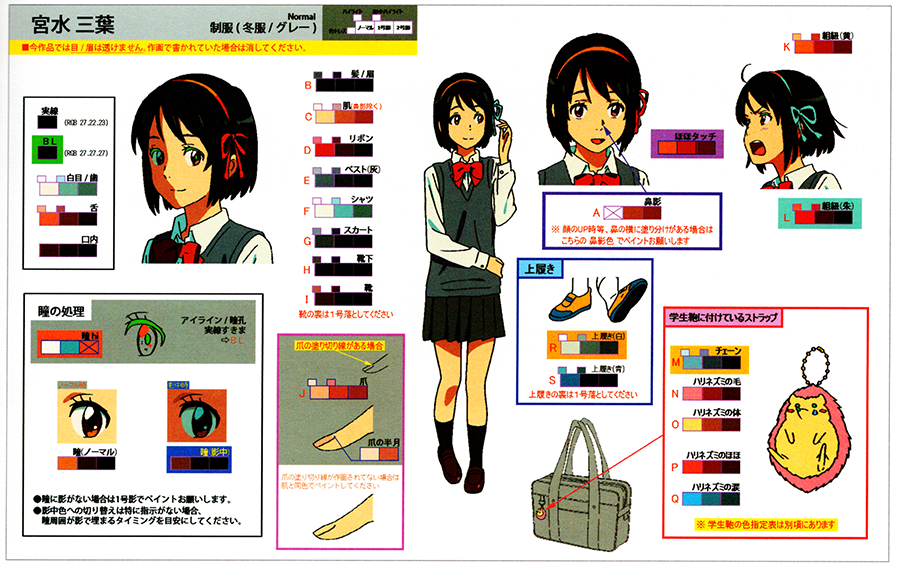

Color Designs

Lastly, let’s touch a bit on color designs. Productions tend to have a figure along the lines of Color DesignerColor Designer (色彩設定/色彩設計, Shikisai Settei/Shikisai Sekkei): The person establishing the show's overall palette. Episodes have their own color coordinator (色指定, Iroshitei) in charge of supervising and supplying painters with the model sheets that particular outing requires, which they might even make themselves if they're tones that weren't already defined by the color designer. (色彩設定/色彩設計), who comes up with the general concept for the palette to be used in that work. There’s obviously a thematic factor to this – choosing from vivid colors that pop out of the screen for lively anime to appropriately moody worlds – but it’s also very concrete work, since they detail the exact tone for every element; the reference sheets they create for the painters list all of those colors to be applied with specialized painting software (like RETAS Paintman) under diverse circumstances. No matter how thorough they are however, anime tends to feature so many settings that specialized Color Coordinators (色指定) are required. They’ll be put in charge of individual episodes/acts of a film, and with the approval of the designer they’ll produce specific variations of those color sheets to fit very particular scenes; a nighttime episode with unusually brighter tones, maybe non-standard variations for dramatic purposes as seen in the first season of Jojo. These coordinators also end up serving as color inspectors, to make sure that every scene complies with the show’s general reference sheets and their own specific ones.

There’s a potential downfall here that you might be imagining already. This is true for all design elements, but moreso on the color front: it doesn’t exist on its own, it has to feel like a part of the world. Ideally everything will follow the director’s vision, and the color designerColor Designer (色彩設定/色彩設計, Shikisai Settei/Shikisai Sekkei): The person establishing the show's overall palette. Episodes have their own color coordinator (色指定, Iroshitei) in charge of supervising and supplying painters with the model sheets that particular outing requires, which they might even make themselves if they're tones that weren't already defined by the color designer. and art directorArt Director (美術監督, bijutsu kantoku): The person in charge of the background art for the series. They draw many artboards that once approved by the series director serve as reference for the backgrounds throughout the series. Coordination within the art department is a must – setting and color designers must work together to craft a coherent world. will work together to mesh the colors of the characters/props with that of the surroundings…but for many works these two elements are outsourced to different companies, creating room for unfortunate visual incongruity. If you’ve ever seen an anime that gives off a vague feeling that there’s no harmony, the problems likely stem from this.

Whew! That’s a lot of design work! Each production goes through processes like this, so think about how many people it takes to simply prepare the visual groundwork for an anime. Considering how overlooked these aspects tend to be, the people in charge might really be the unsung heroes of anime. See you next time, as we’ll finish this series with a culmination of all this work in the storyboards section!

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

I have tried to find some info about the actual intellectual process behind color design for a while now, both in Japan and the West. If anyone knows anything more… I would even be ready to pay for an interview!

Depends on what do you want – color designers talking about their thought process behind a project, or them talking about the job as a whole.

I know what the job entails in terms of tasks, but I never once saw a color designer say how they go about it: the skills they use, the choices they make, the rationale behind them, etc. I have so many questions.

I would be highly interested in an interview like that as well.

I would recommend James Gurney`s books on color and light as well as color psychology by Eva Heller

Thank you very much for these suggestions! However, I cannot seem to find Heller’s book in English (or French, for that matter)…

“As most animation production studios lack an art department” how is that even possible….

Many anime studios choose to focus on the animation and directional workload…and can’t really handle those to begin with, so creating a department that relies on an entirely different skillset isn’t high on their list of priorities. It’s been shown time and again that teams working close by is positive, but not everyone can pull it off.

Could you please x plain me what’s a screen design cause it’s not mentioned here , but I heard it comes under compositing/photography department.