Hyouka: Character Expression Through Inventive Adolescent Daydreaming

As the finale of this month’s Hyouka coverage we’d like to share this look into one of the aspects that make it such a special show: the recurring fantasies in an otherwise grounded series, which each episode’s staff was given immense creative freedom for. The results were unique aesthetics applied to sequences that articulated the inner feelings of the characters much better than dialogue tends to do.

In the many interviews with Hyouka’s core staff that we’ve been publishing over the last month, there’s been one neat point that series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario. Yasuhiro Takemoto has kept on bringing up: he didn’t only allow individual storyboarders to come up with their own unique fantasies, he actively encouraged them all. The result was, as he had desired, countless sequences that escape the show’s usual aesthetic, and sometimes standard hand drawn animation altogether.

It’s a recurring quirk to make the presentation of all the clues required for the show to work as a mystery piece visually engaging, but there’s an even more interesting aspect: Hyouka is a subjective tale, never depicted through a neutral lens. We’re constantly invited into the minds of the characters, Houtarou’s in particular, not just to see the world through their eyes but also imagine it through their insecure, troubled minds – when the staff said they treasured their vulnerabilities, that was no joke! Those often reshape the most striking scenes in the series, so a rundown of Hyouka’s most memorable fantasies seemed like a good way to wrap up this coverage.

─ We couldn’t start any other way than with Chitanda’s first iconic I’m curious. As the series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario., it’s no surprise that Takemoto’s daydreaming sequences are the ones that through metaphor capture Houtarou’s psyche the best. While they’re not the most idiosyncratic when it comes to the craft, Takemoto uses striking imagery – quite literally flowery in this case – to perfectly articulate how Houtarou feels. He’s been trapped in Chitanda’s eyes ever since their first meeting, caught in a beautiful net that he quickly cuts to again at the end of the first segment. It’s not just the rosy moments that get this special treatment though, since he also quickly establishes how overwhelmed Houtarou can feel when faced with the enthusiasm of his peers; that nasty feeling is shown as he drowns in the school club’s passion, taken the form of words from the cluttered billboard.

─ Takemoto himself also storyboarded the second episode, although with Hiroko Utsumi’s assistance as episode director, so it’s no surprise that it followed a similar pattern. Layouts like this depict reality as distorted through Houtarou’s lens – even when the physical distance is small, the emotional gap he perceives between himself and his spirited acquaintances is massive at this point. And once again his main fantasy is triggered by physical contact with Chitanda (whose utter disrespect for his personal space is wonderful), taking us to an alternate reality that gets to the heart of the issue: even when faced with choice, saying no to Chitanda isn’t really an option for him. That he parses this as her forcing his hand only makes him more adorable.

─ And speaking of Houtarou’s cute interpretations, the third episode begins with his misunderstanding of Chitanda asking him out as a confession. The world remains virtually the same, save for a rose tint and a morphing pendulum, which are enough to create palpable romantic tension… until she voices her request and it all returns to normality. This approach, to entirely change the feel of an otherwise standard setting through the colors and postprocessing, is something Taichi Ichidate does on a regular basis – during all his career, within this show, and even in this episode. It’s also appreciable when they’re looking back on the crime scene, re-explored as a pop dream.

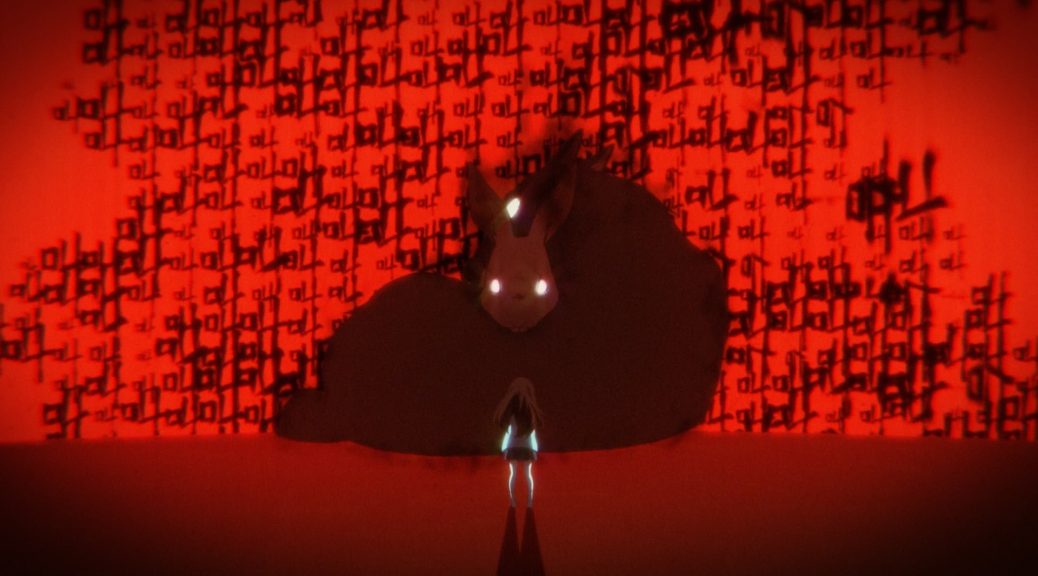

─ Yoshiji Kigami brings closure to the first arc with some of the most memorable imagery in the entire series. Hyouka‘s very grounded atmosphere, which even makes it feel unusually solemn for a series about highschoolers, is what makes these special sequences stand out so much. The show deals with very personal and small-scale conflicts so being loud wouldn’t make much sense to begin with, but that doesn’t mean it pulls any punches. The truth behind the Classics Club’s anthology is presented in gruesome fashion once they find out that the rabbit sacrificed by his immutable peers to face the hound-like administration was Chitanda’s uncle, the one they had been trying to figure out; Kigami’s episodes having the most spectacular animation the studio puts out is a very regular outcome, as this excruciating depiction of inner pain goes to show. Though more than the actual events, what motivates her curiosity is finding out the feelings of the people involved in these cases. And this time around it’s her own, as she recalls the shocking experience of being told what it’s like to be alive but dead, to have a mouth but not being able to icecream.

─ On a much more relaxed register, Kazuya Sakamoto‘s sixth episode proves how funny these delusion sequences can be. The club members begin by joking about Chitanda’s angelic character (Uriel, Gabriel, Chitandaえる might be the best bad pun in the show), Houtarou briefly sees her as one when she lies about her secret desire to save up energy… and then we’re back to the usual dynamic, with him overwhelmed by curious angel Chitanda gremlins. There’s also an interesting sequence when she tries to recall what happened in class to spur her curiosity this time around: since the explicit mystery is again the actual feelings of the people involved in the incident, she’s surrounded by sterile mannequins, who only wear exaggerated expressions as masks – whatever lies behind those is their goal!

─ Since I’ve brought up the presentation of the mystery elements, it’s worth noting that there are many neat sequences in the early episodes. Look no further than Ishidate’s #3, where someone reading a newspaper transitions into Chitanda’s memories in the form of a pop-up book. Utsumi didn’t discard 2D animation, but the aged textures and creepy Ohira-esque silhouettes in her horror tale also managed to stand out. Many directors opt for a dynamic presentation of the text, be it through 3D and motion graphics or accompanying it by eye-catching pieces of hand drawn animation. Eisaku Kawanami‘s episode 4 had to focus in this regard the most, since he illustrated a meeting where each member exposed the clues they’d found and their own theories. And each of them does so in their own unique way, trying to stay fitting to the character and even the time period, thus ending with Houtarou’s exposition that is basically framed as the detective in an old mystery.

─ The End Credits of the Fool arc, where the Classics Club has to figure out the intended ending of a student movie, shakes up the formula quite a bit. Early on there are essentially no notable daydreams, so the staff’s special presentation efforts instead went on to masterfully replicate a disaster; all the quirks you’d expect from an immensely amateur production are there, from the camera to the varying degrees of investment by the cast. Noriyuki Kitanohara isn’t considered one of the studio’s most resourceful directors, but he proved he’s not just a capable animator who just happens to supervise episodes sometimes. And honestly, seeing so much effort put onto faithfully capturing the feeling of poorly made cinema is just amusing.

─ Episodes 10 and 11 return to the earlier approach with two recurring directors, Sakamoto and Kitanohara. The emotional rollercoaster begins with Irisu Fuyumi’s emotional manipulation of Houtarou, aided by a false anecdote shown as a shadow play. She exploits his very human desire to be special, convincing him that he has extraordinary talent solving mysteries that he must put to good use. And so, the scene where he goes over the footage of the film again and makes his deduction is presented in grandiose form, as if he were a true master detective. Things don’t work out all that well however, so after realizing he was prioritizing himself and disregarding the feelings of other people – in particular those who actually made the film he was supposed to solve – Houtarou sees himself as the detective under the spotlight, surrounded by puppets and audience that he only wanted to applaud him.

─ The Kanya Festival that occurs during The Order of Kudryavka arc is broadly considered Hyouka’s peak, and for good reason. But with the angle we’re taking with this post, it’s also arguably the lightest segment in the series; the first three episode directors in charge – Taichi Ogawa, Naoko Yamada, and once again Kitanohara – captured the liveliness of a school festival like no other anime, while Taichi Ishidate handled the thematic and narrative closure in #17 masterfully. Instead it was Hiroko Utsumi who, through episode #15, got to sprinkle the arc with a bit of fantasy, and in an unusual way too. For once we get to see the world filtered through the eyes of someone other than Houtarou, as it’s Satoshi’s and Chitanda’s imagination that is given form this time. The former wants to exploit the coolness he sees in Houtarou’s detective skills to promote the club (sold as a joke here, but very much related to his poignant arc), while Chitanda struggles to put to use Irisu’s misguided advice on how to control people. Utsumi later returns in episode #21 to briefly bring to life Mayaka’s bold Valentine’s resolve as well. Besides the fact that she got to depict the minds of the rest of the Classics Club, what remains consistent is her high-contrast style; colors, angles, even the sharpness of the drawings increases when she’s personally in charge. It didn’t always work, but her boldness made her stand out from the rest of KyoAniDo directors.

─ The next two episodes serving as a bridge into the final stage take more or less opposed approaches. Kitanohara’s episode 18 is a very natural follow-up to previous material: an amusingly relevant clip of mushrooms getting zapped segues into Houtarou’s deduction, which has recovered a bit of its grandeur now that he’s much more comfortable with the role of the detective. On the other hand, Ogawa’s #19 presents a new situation. The entire episode is dedicated to a mental exercise that Oreki and Chitanda get lost into, which shakes up the mystery formula down to its craft. Since it’s all theorizing based off a single point and no new information comes into play, the mystery is all presented in a visually consistent way; this time it’s mostly stylized, game-like silhouettes as motion graphics, although they found a way to bring hand drawn animation into play too. At the end, Houtarou immerses himself in that world until he can finally imagine the solution to their made up (or is it?) mystery. That is depicted in a very distorted way, since for a change they’re dealing with actual crime-solving, a darker kind of mystery that the show doesn’t delve into.

─ No one better than the series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario. to wrap up this fantastic show. Takemoto had a final trick up his sleeve when it came to Houtarou’s illusions: the very end of the series momentarily fools the audience with an indistinguishable what-if, since at this point his fantasies are closest to reality than they have ever been. And even though he can’t quite bring himself to tell Chitanda those words yet, the same wind from his dream ends up blowing in the real world. Takemoto wanted this series to feel like just one year within lives that extend in the past and future, and with this he firmly established what will eventually happen.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Video on Youtube, as well as this SakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

Takemoto and Ishidate directed the last episode, with Takemoto storyboarding. This like the inverse of the last episode of Lucky Star which had Takemoto and Ishidate storyboarding and Ishidate directing.