The Evolution Of Kyoto Animation: A Unique Anime Studio And Its Consistent Vision

Article pinned in memoriam of everyone who lost their lives in the terrorist attack today at the studio. We can only extend our heartfelt condolences to the victims, everyone’s families and friends, and all affected parties in general. Please take care.

Full Metal Panic? Fumoffu! began its broadcast in August 25, 2003, exactly 15 years ago today: a remarkable event not just because it was an amusing series, but because it was the first TV anime produced by Kyoto Animation. How have things changed for them since then, and what was the long road that led them there like? This is the story of one studio that’s had a very clear philosophy many years before their grand debut, and how that’s led to tremendous success and an unusually good working environment, but also the curious issues they’ve had to tough it through. Find out why KyoAni are one of a kind!

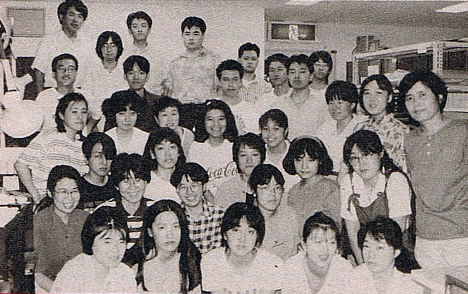

Housewives painting anime cels

Yoko Hatta, a painter with experience on classic titles like Princess Ribbon at Mushi Production, left the studio and moved to Kyoto after marrying Hideaki Hatta. Once she was there, she gathered a few housewives from the neighborhood with time to kill under the name Kyoto Anime Studio, dedicated to painting cels for Tatsunoko Pro and Pierrot productions for the most part. They began appearing in anime credits in the early 80s, including titles like SDF Macross, the Time Bokan series (Ippatsuman and Itadakiman), Genesis Climber Mospeada, Pierrot’s classical magical girl titles, Mirai Keisatsu Urashiman, Urusei Yatsura, and so on. Not all of the initial members – Emiko Honda, Akiko Fujimura, Ayako Takemura, and of course Hatta herself – stayed as they transitioned from a semi-professional crew to a more serious endeavor, but it already set the tone for what would become a studio with a predominantly female voice.

Come 1985, Hatta made an important decision: founding an actual company, Kyoto Animation, which would have her husband Hideaki Hatta as the president but keep her as the actual head of operations; that arrangement hasn’t changed throughout the studio’s lifespan, and to this day she still has the final say on their anime projects. They slowly began to be credited under the company’s new name, though the Hattas always kept Kyoto Anime Studio in their hearts – hence why it was credited for the composition of KyoAni’s first independent anime decades later. It’s hard to forget your own roots.

But let’s not get too ahead, since those early stages of the studio were chock-full of important developments. Just one year after formally coming into existence, Kyoto Animation created its own animation department, later followed up by an art crew, and eventually a photographyPhotography (撮影, Satsuei): The marriage of elements produced by different departments into a finished picture, involving filtering to make it more harmonious. A name inherited from the past, when cameras were actually used during this process. department in the late 90s. As time passed it became a regular occurrence to see their name supporting important productions, be it drawing in-betweensIn-betweens (動画, douga): Essentially filling the gaps left by the key animators and completing the animation. The genga is traced and fully cleaned up if it hadn't been, then the missing frames are drawn following the notes for timing and spacing. (Kimagure Orange Road, 1987), key animationKey Animation (原画, genga): These artists draw the pivotal moments within the animation, basically defining the motion without actually completing the cut. The anime industry is known for allowing these individual artists lots of room to express their own style. (Dirty Pair OVAs and Mister Ajikko, 1988), or even background art (Neon Genesis Evangelion, 1995), all while also doing minor assistance work on notable theatrical works like those of Ghibli or Akira. It’s important to note that this wasn’t notable in itself, since we’re in an industry where everyone has to help their peers, but their ability to regularly tackle sizable chunks of whatever they were entrusted with and produce high-quality work did earn them quick acknowledgment.

The earliest important instance of this dates back to 1987. The studio hadn’t been around for long, but by that point they had assisted enough Tatsunoko projects to catch the eye of now-legendary producer Mitsuhisa Ishikawa. At the time he was looking for a way out of the studio, so when time came to produce Zillion, he entrusted Kyoto Animation with the co-production of the series… though by his own admission, instead of splitting the work with a Tatsunoko sub-unit, it actually ended up being KyoAni’s first production of sorts – not quite manufacturing the show since they weren’t prepared for that, but effectively managing its production. This fully earned Ishikawa’s trust and established a subtle yet crucial bond, as later that year Hideaki Hatta became one of the initial shareholders on Ishikawa’s new subsidiary IG Tatsunoko. KyoAni playing a role in the existence of an entity as massive and seemingly unrelated as Production I.G is one of those pieces of trivia that are always fun to think about.

The road to establishing an individual style

Proficient as they may have been, it’s impossible to develop much of a unique flavor if all you ever do is handle single elements in other people’s productions. Artists like Takeshi Kusaka established themselves as important figures in the studio’s infancy, and yet they were missing any personal flair. This would be a perfectly fine situation if your aim is to be a support studio, but as you can imagine, that wasn’t the case. The first step to move forward, naturally, was to begin making their own episodes and short films. And out of all the things it could have been, Kyoto Animation’s first self-contained piece was Shiawasette Nani: a 1991 short film contracted by the controversial Happy Science cult; far from being noteworthy on its own, even if it did accidentally tease out some creative roles we would see over and over years afterward. Requesting preachy material from KyoAni became a bit of a trend, seeing how they also got tasked with educational OVAs by the government. Maybe all the Haruhiism jokes of the 00s were fated to be.

If you want to understand the direction the studio took though, you’re best served by looking back at 1992’s Noroi no One Piece, a co-production with Shin-Ei Douga that served as Yoshiji Kigami’s directorial debut. Just about every part of that sentence changed KyoAni’s identity and still has a massive effect on them nowadays, so even though we’ve got to summarize the situation, it’s important to get across the basics. While the two studios had begun establishing a link prior to this project through assistance on franchises like Doraemon, this can be considered their first major collaboration. Quite the important development contained in a mostly forgotten VHS!

Kigami was one of Shin-Ei’s animation aces – first as an actual member of the studio and later attached to Animaruya, a group of talented ex-members who still worked for them – so his first bout as director was a noteworthy event. We’re talking about someone talented enough to be considered a rival by the one and only Toshiyuki Inoue! Kigami had already shown his alluring comedic fluidity and his grasp of his mentor Hiroshi Fukutomi’s complex camerawork when working on Sasuga no Sarutobi. And just as importantly, he’d left a very strong impression working on iconic movies on the rise of realism in anime; not many people can boast about having penned some of the most impressive scenes in Grave of the Fireflies and Akira. And he wouldn’t do it, but he definitely has the right to.

Noroi no One Piece is a collection of unsettling short tales penned by Shungicu Uchida, all revolving around a cursed dress that brings misfortune to its wearers. What makes it so interesting isn’t its straightforward yet effective horror trappings, but rather the impeccable character expression, mixing attention to gesture with the right levels of elasticity in the animation; this kind of thorough acting would feel exceptional at the best of times, let alone for the debut of both a director and a studio for what was supposed to be a small project. Kigami saw a diamond in the rough within KyoAni: the makings of a technically brilliant creative crew, waiting for the right person to arrive and polish them up.

And from that point onwards, that was exactly Kigami’s role. Rather than conveying purely technical aspects – which he also did, to the point that even nowadays most animators at the studio draw effects in Kigami-like shapes – what he made an effort to spread was the Shin-Ei attitude of not cutting corners. Not just to go all out during isolated hectic scenes, but to be extremely meticulous when depicting the demeanor of the characters as well. This simple precept that has led to the studio’s unique animation identity has been misconstrued as an attempt to place subdued acting above all, which is slightly off the mark. Kigami is no stranger to exaggeration and outrageous cartoony animation, having directed some of the most extreme episodes in projects like Nichijou. As far as I can tell, simply being willing to be equally fastidious when depicting everyday life is so exceptional in the TV anime space that it can make people feel that’s all there is.

Kigami’s humane approach resonated with the studio from the get-go. KyoAni may not have had a defined style yet, but the team did already have a clear ethos. People often ask why other anime production companies don’t mimic the Kyoto Animation model, if it’s so positive and has directly led to their success. The answer is simple yet discouraging: as seen in this 1992 feature by Masahiro Haraguchi, they’ve had to stick to their beliefs for a long time to become what they are; the explicit mentions of communication between the staff in a shared space, the workplace oozing with gentleness, trying to handle every step in the production process, the female staff preeminence – these are all points that are brought up now to explain what makes them unlike their peers, and yet they were already a factor decades ago. Try as they may, it’s not easy for other studios to emulate this, especially since taking management risks now is even more dangerous in today’s climate.

Deluxe outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio. studio

This ability to deliver high-quality work right off the bat earned the attention of major studios, always on the look-out for new capable hands. It’s easy to see why working with them became such an appealing prospect. KyoAni proved that they were a very consistent assistance crew, as seen by the 33 episodes of Inuyasha they fully produced while also providing help to other staff in the series. Their work was solid at worst and exceptional at best, and yet they could keep things fairly inexpensive due to their location and by avoiding further subcontracting, since they had all departments required to make anime. Viewers nowadays associate anime outsourcingOutsourcing: The process of subcontracting part of the work to other studios. Partial outsourcing is very common for tasks like key animation, coloring, backgrounds and the likes, but most TV anime also has instances of full outsourcing (グロス) where an episode is entirely handled by a different studio. with bad production practices… which to be fair tends to be true, but that wasn’t always the case. For about a decade, subcontracting work to Kyoto Animation was a very smart move.

The result of that allure was endless calls for help. It’s often said that the studio’s excellent schedule management, another defining trait, was developed while juggling all the requests they received in this period. During the 90s and early 00s they were all over the place, starting with productions handled by their old acquaintances. They kept on helping Tatsunoko and especially Shin-Ei’s Doraemon and Shin-chan franchises, peaking with contributions to their theatrical projects where the uncompromising approach the studio had inherited from Shin-Ei in the first place felt right at home. Old companion Pierrot also got a good taste of their skill, not only through various TV shows but also when they let a greenhorn company like them essentially produce an entire Kimagure Orange Road movie. Even the videogame industry quickly reached out to them, which allowed various franchises to feature opening sequences animated by KyoAni.

With 4 openings and 1 ending sequence, Konami’s PawaPuro franchise is the game series that KyoAni contributed to the most.

Their plentiful output at the time makes this a fascinating period in their history, but to get a good grasp on the studio’s history, we need to separate the countless curiosities (like this collaboration between Mamoru Hosoda and KyoAni) from the meaningful developments. Truth be told, not all subcontracted work is made equal. Those led by Kigami were as wonderful as the resources were realistically allocated and then some (especially when he could supervise and provide animation on top of directing), whereas those in the hands of the new generations were generally more modest at first.

Who stepped up to the plate then? Tatsuya Ishihara is an interesting case, since he was never all that invested in the animation process and jumped onto directorial opportunities the second they presented themselves. He became their most ubiquitous director and developed a sense for moderate slapstick comedy that was very rooted in its time, which makes his current output feel amusingly anachronistic when it comes to humor. This stands in contrast with Yasuhiro Takemoto, who had similar origins, save for the fact that he was more enamored with animation, and yet came to go down a very different path. He gradually developed that understanding of physical space that makes his works so special, and gained even more unique flair when coming in contact with Akiyuki Shinbo for the production of The SoulTaker. Though he’s grown to be more of a solemn director that a flashy one, he’s kept that appreciation of chiaroscuro shots and monochromatism with accents, plus that surreal staging for situations that require it.

Working alongside Tsutomu Mizushima on Hare+Guu was a formative experience for Takemoto and the rest of the studio, which still share similar comedic sensibilities.

Other figures rose within the studio during that period (like Yoshiko Shima, KyoAni’s first female director), but if I had to highlight someone as their new ace, that would undoubtedly be Tomoe Aratani. Although she joined the studio much later than all the aforementioned staff, her talent and versatility quickly made her stand out. It didn’t take her long to become a regular storyboarder on Inuyasha, a supervisor and director wherever it was needed, the studio’s first dedicated character designer, and even an animation mentor to all her peers. Her keen awareness of body movement and ability to extrapolate realistic mannerisms onto stylized cartoon forms made her the perfect asset for the studio, and she did her best to spread her teachings around. KyoAni’s predilection for placing women in animation directionAnimation Direction (作画監督, sakuga kantoku): The artists supervising the quality and consistency of the animation itself. They might correct cuts that deviate from the designs too much if they see it fit, but their job is mostly to ensure the motion is up to par while not looking too rough. Plenty of specialized Animation Direction roles exist – mecha, effects, creatures, all focused in one particular recurring element. and character design roles can easily be traced back to Aratani’s positive impact in these early stages. Beyond gender itself, this is simply a neverending attempt to try to capture the same magic – which they did and more, as we’ll see later.

New era for anime, new era for the studio

To understand how quickly things escalated after that, you have to keep in mind the changing landscape for anime as a whole. The industry was about to ditch traditional cel production, and despite their roots doing just that, Kyoto Animation seized the opportunity to grow at hand by getting acquainted to the new ways of production before the rest of the pack. The situation is comparable to the studios currently ahead of the competition when it comes to digital workflows – the likes of Colorido, which unsurprisingly features some artists of KyoAni origins among their ranks. It’s hard to tell when the next game-changing development in production will happen and what it will be (perhaps truly trustworthy automated in-betweening?) but whoever exploits the new possibilities first will surely reap massive benefits, even if they’re newcomers.

What was their first independent offering like, then? Munto was juvenile, often awkward, coming across like Yoshiji Kigami’s own teenage fantasy dreams made into a cartoon. At the same time, it was an astonishing animation feat that easily ranks among the most spectacular studio debut works. It’s worth noting that the first OVA and its 2005 sequel actually channel the team’s action and effects capabilities first and foremost, which brings the result much closer to anime’s regular sakugaSakuga (作画): Technically drawing pictures but more specifically animation. Western fans have long since appropriated the word to refer to instances of particularly good animation, in the same way that a subset of Japanese fans do. Pretty integral to our sites' brand. showcases than the studio’s output usually is. Instead it was the 2009 incarnation of the series – quite the messy format it ended up having, perhaps deservedly so – that went out of their way to humanize the characters through their acting in that distinctly KyoAni-like way.

Their first TV series, which has now reached its 15th anniversary, was none other than Full Metal Panic? Fumoffu!; a spinoff that represented quite the change for the franchise, switching studio and genre in one fell swoop. Back when he directed his first series, Yasuhiro Takemoto hadn’t yet developed the sense of warmth that nowadays gives his works a recognizable flavor even when he handles very different genres, that special touch that makes works as different as High Speed! and Maidragon feel like they share a meaningful something. However, it did put all his eccentric comedy experience to good use, including an episode fully storyboarded around the concept of ingeniously hiding nudity that has to be seen to be believed. There’s a reason that he’s still one of the go-to staff members when it comes to surreal humor, despite viewers associating him with stoic work.

It’s worth noting that, while Fumoffu! is by all means KyoAni’s first show, it’s not fully theirs like the productions that followed it. Capable as they were, the studio simply didn’t have enough staff to make an entire series without compromising quality. The solution to this problem was to fully outsource 4 episodes to Tatsunoko, who had accompanied them in this anime adventure since the very beginning; a touching role-reversal, in spite of the fact that these subcontracted episodes sort of failed to live up to the execution of the rest of the series. The experiment paid off either way, and by the time Full Metal Panic: The Second Raid (the last FMP season that’s avoided having its production horribly implode) was broadcast in 2005, the studio was already capable of producing an entire TV show.

The Goose That Laid the Golden Cartoons

If we’re talking about 2005 KyoAni titles though, the project that had the biggest impact was without a doubt the adaptation of Air. Which means we’ve got to switch protagonists back to Tatsuya Ishihara, who happened to be a big fan of Key visual novels and strongly pushed for this project. As it turns out, Ishihara’s preferences had massive industry-shifting consequences. As a big otaku himself he’s always understood what attracts fans (mostly the male ones) to the world of latenight anime, but his polite and pleasant delivery has historically given his works an unexpectedly broad appeal. Once you notice this, you can understand how he cemented the visual novel anime boom through adaptations with a surprisingly broad appeal, and how one year later he would revolutionize the anime world entirely with The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya. This ability is something he passed onto his pupils as well, as seen in the wild success of K-ON!, and it’s become one of those intangible factors of the studio’s success.

It’s easy to fast-forward through this period, not because the works they produced aren’t worthy of attention in one way or another, but due to the remarkable consistency the studio achieved. Air was followed up by other Key titles like Kanon (2006) and Clannad, gradually refining the skill of the studio’s ever-increasing directorial crew regardless of how clumsy the tales they adapted may have been – not that this ever got in the way of their tremendous success. At the same time, the studio’s partnership with Kadokawa led to even more massive hits like the aforementioned Haruhi and Lucky Star, titles that defined the anime fandom worldwide for years. Even as they took a risk by entrusting an obscure IP to a newbie director, K-ON! turned out to be one of the most successful anime of all time. A curious belief spread: that no matter the vocal detractors, in the end the results showed that KyoAni could basically do no wrong. Even the studio basked in their own popularity by including plenty of references to their other titles in a similar way to what TRIGGER does now.

The company’s management also appeared to follow a consistent path. The stable, high-quality productions became an integral part of what made them special, even more so as the rest of the industry generally headed into a downward spiral. The studio philosophy made explicit in that 1992 article was reinforced with time: a family mentality among the team and the development of all departments involved in animation. To consolidate this unique culture, the studio started focusing on fostering new talent as their number one goal; the KyoAni School began running with the studio’s staff as instructors, and company recruitments were limited to youngsters as well, so everyone working in their projects had a shared set of skills and beliefs that made them more likely to work well together. KyoAni’s works were unlike the rest, made by full-time employees who no matter their (sometimes stark) artistic differences, shared the same fundamentals. The staff developed a clear identity that made it very easy to either love them or hate them, and the former appeared to be the more common reaction.

This isn’t to say that everything went perfectly, as seen by the great exodus of the mid to late 00s. Creators leave the studio on the regular, often attracted by the allure of freelancing life even though they know their working conditions will take a hit. Some key figures have resigned throughout the years: the aforementioned Aratani temporarily transferred to Nintendo following a local program and enjoyed the experience so much that she stayed there, whereas the brilliant Noriko Takao felt the harsh competition to earn a series directorSeries Director: (監督, kantoku): The person in charge of the entire production, both as a creative decision-maker and final supervisor. They outrank the rest of the staff and ultimately have the last word. Series with different levels of directors do exist however – Chief Director, Assistant Director, Series Episode Director, all sorts of non-standard roles. The hierarchy in those instances is a case by case scenario. spot was so overwhelming she fled to A-1, where she’s arguably become their top director.

Aratani is currently in charge of cinematic design on games like Zelda Breath of the Wild, but her animation skills will never get rusty.

While those talent leaks do hurt, they’re generally compensated by the studio’s endless quest to train new artists. What happened at the time, however, was a bigger deal. Unfortunately, to explain what happened I have to bring up Yutaka “Yamakan” Yamamoto, the anime equivalent of crossing Anakin Skywalker with Jabba the Hutt. He was supposed to be the chosen one after all. Yamamoto was the protégé of Kigami and new leading voice of KyoAni’s Osaka branch Animation Do, which had existed for many years (though it only became its own entity in 2000) but began developing a culture of its own under his leadership. After playing a key role in Haruhi, being famously responsible for its iconic dance, Yamamoto was entrusted with Lucky Star… and then removed from the directorial seat after 4 episodes, accompanied by a suspicious blunt note by the studio indicating that he didn’t have the skills to direct a TV show yet. Soon afterward, he left the company altogether and a bunch of his co-workers followed him.

Yamamoto ended up founding studio Ordet, where he gathered the people who followed his steps and other ex-KyoAni members who had departed the studio during the 00s. Their first offerings were very impressive as a consequence, from the amusing Kannagi that they heavily assisted to the astonishing 2010 Black Rock Shooter OVA, your one chance to see KyoAni-bred animation muscle work alongside Yutaka Nakamura. And yet, that was pretty much the end. How come Satoshi Kadowaki immediately left him and is now one of WIT Studio’s main assets? Why did Masaharu Watanabe instead decide to focus on Naruto under the name Gorou Sessha, before starting his own directorial career with the likes of Re:Zero? Why did Yusuke Matsuo abandon him and become a massively popular designer elsewhere?

The answer, to put it plainly, is that Yamamoto is an insufferable asshole that only got more rotten with time. Rather than gather around him, almost all his coworkers quickly found new destinations. The rumors about inappropriate sexual behavior being a factor in his departure gained credibility after stunts like publicly tweeting that he’d have to “hold back on sexual harassment-ish things” with voice actress Minami Tsuda, among many other appalling statements. So even though it led to the departure of some talented people and a chunk of the workforce, perhaps even this incident eventually had a positive outcome for the studio.

Self-sufficiency and complete isolation

What do you do when seemingly everything goes right, then? Stick to your path and do more of the same you say? Actually, you scrap your formula for success and make fundamental changes to your output to screw over your fanbase… or at least that’s how people who fell in love with their Kadokawa-era titles like Haruhi and FMP would like to frame the situation. Something I purposely neglected to mention earlier is that one of the important new developments of their early independent stage was to launch the KyoAniBon. The first of 25 volumes of this web magazine was released in March 2007, as an attempt to reach out to fans directly with interviews, behind the scenes clips, but also by sharing many pitches of potential projects by various staff members. The desire to make anime truly of their own was clearly there, also made obvious by the animated commercials they began putting out.

Getting that across is important because it helps you understand why they’d move away from a model that had been so ridiculously successful, stepping away from popular IPs to start handling dubious titles they have ownership over. They first announced the yearly KyoAni Awards where the staff would give prizes to the amateur submissions they liked the most. Those books would then be published by their new KA Esuma imprint and adapted into animation if any director was up to the task. A controversial decision to this day, and yet entirely coherent to the attitude they’d been showing since the 90s. And also importantly, an excellent business move as well. These changes were tied to the studio’s initiative to start leading the production committees of their projects, bypassing the industry’s major issues with actually rewarding the creators whenever a title is successful. Even though it didn’t quite hit the same levels of massive popularity as their 00s peaks, Free! is undoubtedly the franchise that’s been most lucrative for KyoAni&Do, as the main investors and merchandise producers for the series. And its existence would have never been possible in the first place without the change in their model, which now allows the company to be as financially invested in their properties as the staff is emotionally invested in their making. Risky, but so far it’s paid off.

This desire for independence in all respects, to truly be in charge of the anime they make, is the drive behind many of their decisions. Their self-sufficiency in production matters hasn’t been matched by any other studio in anime history, which makes them the object of envy for other companies and marks the path to follow for others. Studio leaders have come to understand that their attitude towards work isn’t a quirk or them just being nice, but rather an ingredient to their success; the unmatched stability of KyoAni’s quality can’t be explained without their top team of in-betweeners, which features some people who have been doing what’s a criminally underpaid task elsewhere for decades, working alongside newcomers to train. Making animation is a stressful endeavor either way so working at KyoAni is far from a dream job unless you already are hopelessly in love with the art, but it’s comforting to see a successful company that ensures the work you’re seeing wasn’t put together by overworked, underappreciated staff who won’t even be rewarded if it turns out to be successful.

Does that make all their moves towards this unique position unquestionably good? I wouldn’t say that’s the case either. As neat as this self-sufficiency is, they had to get there by discarding an excellent set of connections that most studios would love to have. This seems to have an impact not only when it comes to the people actually making the show, but also with the producers who are now so cut off from the rest of the industry that sometimes they don’t seem to have much of a grasp of what viewers want. On an artistic level I believe it all worked out great though, even if the clear identity of their work can very easily blind detractors and make them feel like it’s all exactly the same; an anecdote with the studio’s designers comes to mind in this regard, as during the latest fan event they showed real curiosity about what viewers perceived to be the “KyoAni animation style”, since they’ve worked together forever and feel like they’re all worlds apart. It’s a matter of perspective and the personal quirks being able to resonate with you or not!

KyoAni in 2018: 15 years of independent creation

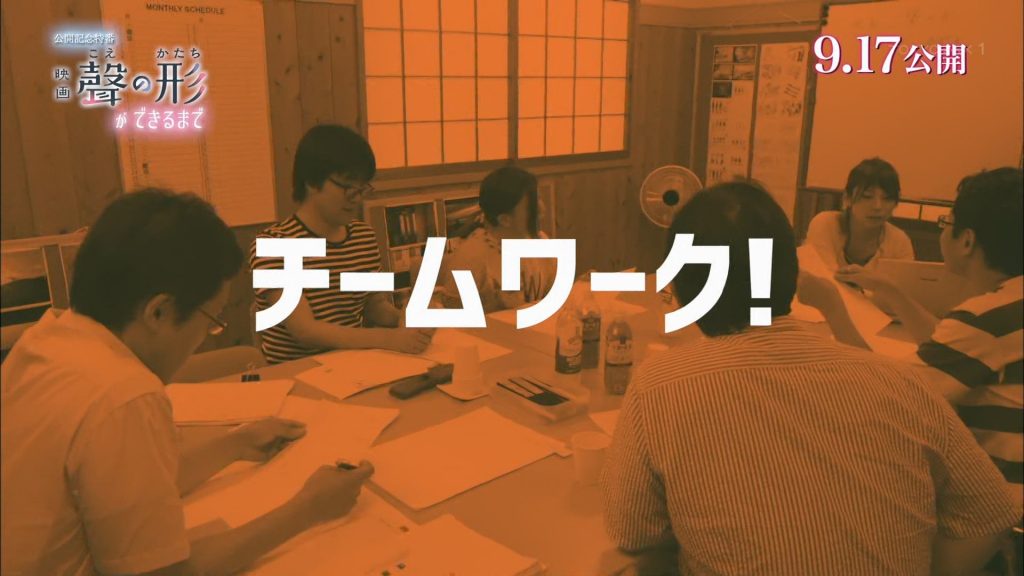

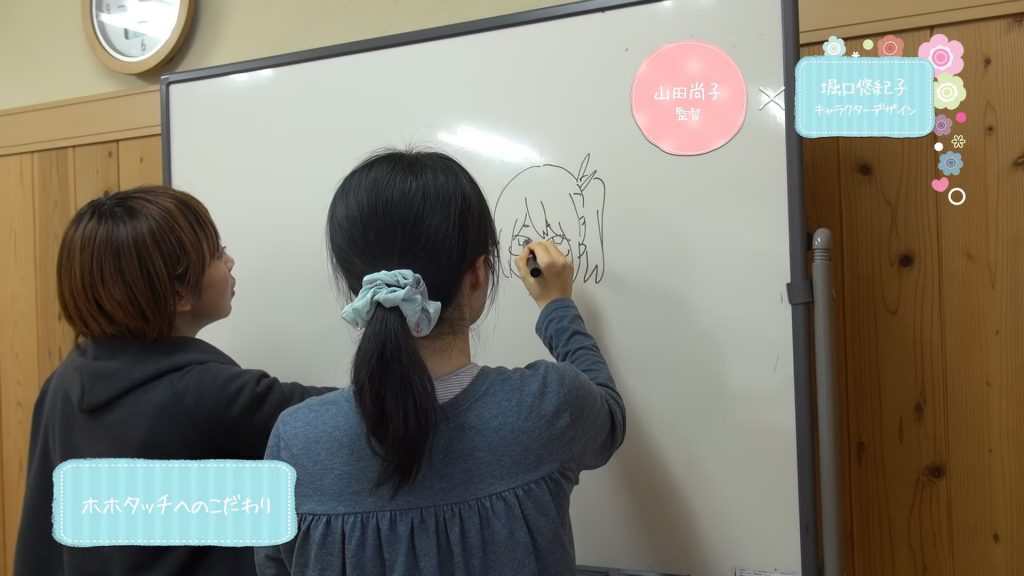

The latest stage in Kyoto Animation’s evolution is plagued with understated yet meaningful changes. The company’s kept on growing, having recently inaugurated a new building that includes a fancier store and animation Studio 5. As they recently passed the 200 employees landmark, KyoAni are now among the top anime studios in sheer size, let alone relevance. This weight in the industry now allows them to approach new kinds of projects and still lead the production committees, as seen in the Euphonium franchise but most impressively in Koe no Katachi – a huge movie adaptation that was truly in their hands.

As interesting as those management changes may end up being though, I’d like to wrap up with a look at the latest stylistic trends at the studio, to help people truly grasp what Kyoto Animation is like now. For example, it’s important to note that it was Takemoto’s attitude during The Disappearance of Haruhi Suzumiya (the studio’s first true theatrical project) that made the studio as a whole switch gears and become even more uncompromising. The obscene quality of the likes of Hyouka can’t be explained without the director’s obsession to create something that felt like a genuine step up during his previous project.

And this didn’t come down to only the animators: it was all departments working together, exploiting that weapon unique to KyoAni. Photorealism that couldn’t be achieved without the cooperation of art and photographyPhotography (撮影, Satsuei): The marriage of elements produced by different departments into a finished picture, involving filtering to make it more harmonious. A name inherited from the past, when cameras were actually used during this process. departments, excellent color design that makes the more traditional work pop out in an attractive way, and of course animation teams that feel respected no matter their position. It’s not as if gathering staff in the same physical place and exclusively making them work forever is the only path to success in anime, but these people have proved that it’s a damn good one.

When it comes to modern trend-setters at the studio though, no one comes close to the golden duo of Naoko Yamada and Yukiko Horiguchi, a perfect combination we’re now tragically bereft of after the latter left the studio (and animation as a whole, temporarily) in 2014. While that partnership lasted though, the two led a revolution that was arguably comparable to the effect Kigami had on the studio ages ago. Although people understandably point at K-ON! as the title that changed everything, there are actually earlier samples like their collaboration on Clannad AS #3, which let them loose (quite literally when talking about Horiguchi’s animation) to make something entirely unlike the rest of the series; lax drawings that feel adorable rather than crude, bouncy animation that isn’t at odds with nuanced gestures. Even taken to their extremes, Yamada’s live action leanings as director and Horiguchi’s cartoony exaggeration were an excellent, elegant mix, because at the end of the day their desire to breathe life into characters was the same. An attitude that two gifted friends had developed together.

Is there life in a world set after the end of their partnership then? As much as it hurt, of course there is. The unimaginable influence that Yamada has over the rest of the studio, even after losing her original partner, is something that we’ve already covered when talking about her career. With her as the new de facto solo studio leader it’s no surprise that low-key acting is now the bread and butter, but projects like Maidragon reminds us that the spirit from Nichijou and even Haré+Guu still lives. KyoAni appears to trend toward higher detail in the design work because of veteran Shouko Ikeda’s Euphonium work and especially Akiko Takase’s monstrous Violet Evergarden concepts, yet at the same time Futoshi Nishiya’s stylized, virtually kagenashi designs on Liz and the Blue Bird feel like a game-changer. More young series directors than ever before have also recently been promoted, so the studio is currently a fascinating melting pot that no one can quite tell which flavor it will take.

What we know for a fact, though, is that unless a tragedy occurs it’ll still feel like Kyoto Animation: a team of creators who’s had a consistent vision for decades, one that they’ve stuck with through hardships and success.

Support us on Patreon to help us reach our new goal to sustain the animation archive at Sakugabooru, Sakuga Video on Youtube, as well as this Sakuga Blog. Thanks to everyone who’s helped out so far!

Excelent write up. Would you say that Kyoani today is bigger than studios like Toei, Pierrot, Sunrise and other big ones?

Toei and Sunrise are unquestionably bigger – simply larger companies attached to massive corporations. Pierrot has less staff as far as I can tell, but they’re in such a different position that it’s hard to even compare. As far as “standard” anime studios though, KyoAni are definitely up there now.

The other thing to consider, which makes comparing KyoAni to other studios difficult, is that most other studios are smaller in staff but bring on many contractors for projects whereas most (all?) of KyoAni’s staff are full-time employees (not that they don’t also use contractors when they need to.)

The “this 1992 feature” leads to an error message.

Good article, btw. I shared it with my friends.

How was the working condition in kyoani before their success? is the exceptional working condition in the studio today only possible because of their success? or is it something that define the studio even before haruhi and k-on ?

They definitely got better with time (we mentioned their incentives to improve maternity breaks when they announced those last year for example) and sustained success helps when you’re taking decisions like this. That said, one of the reasons I went back to that 1992 article about the studio was because the reporter already noted it was a workplace overflowing with kindness. Mid 00s Hatta also spoke against consistent overtime, especially if it wasn’t properly remunerated too – it’s always been a thing for them. Should always aim at improving though – there’s been some comments about tight deadlines as of… Read more »

It’s always fascinating to learn more about the studio, just as it is painful to get reminded of the loss of Yukiko Horiguchi from animation. What a wonderful AD she was. I actually finished a rewatch of “Hyouka” last night and I noticed something that I don’t see as often in recent KyoAni works as I did in this series. This observation may be incorrect, if so please let me know. With the likes of Naoko Yamada, Haruka Fujita and Taichi Ogawa, I see a lot more focus on a ‘capturing through a lens’ approach. This was there for “Hyouka”… Read more »

Your analysis is very on point in my opinion, though I would disagree in one detail – funnily enough, I don’t think it actually applies to Yamada herself. She’s by all means “at fault” for this because she’s the one influencing the studio as a whole, and without Horiguchi by her side there’s less of that appealing cartoon looseness. Other creators look up to her and try to incorporate that camera lens-like approach to their work, but it’s never as refined in my opinion and can lack that inventiveness you get when combining the two registers. I really do think… Read more »

Indeed I agree with pretty much everything you have said here. I haven’t seen “Liz and the Blue Bird” and I have tried to stay far away from promotional materials, and so a lot of what you pointed out I wasn’t very aware of, however what you’ve said he makes me very excited to watch it! Ishidate has blown me away recently. I’m not a fan of his series productions at all, but his episodes are always among my favourites of a series. I would love for Takemoto to tackle bigger projects, but even the likes of “Maidragon” are really… Read more »

It’s undeniable that the studio lost animation power after 2014. And how could they not, Horiguchi & Naitou are all-time great animators! The young replacements haven’t really made up for it – I don’t think Tsunoda’s very good as AD, Myouken has that special touch but I get the feeling we’re not really seeing her true skill, and Maruko is too safe. Takase is an interesting case because… she shouldn’t even be an animation director? She got promoted faster than people like Horiguchi, and I get the feeling it wouldn’t have happened if it weren’t because she was in charge… Read more »

Agreed “Sound Euphonium” episode 9 was wonderful. I think that’s why “Violet Evergarden” was such a let down. I honestly thought we would get the quality of “Sound Euphonium” episode 9 for the entire series. I do admit to being rather foolish there. I wouldn’t be a very big fan of Chiyoko Ueno, outside of her amazing drawing range. Although I loved her AD work in “Miss Kobayashi”! I would have to say for me at the moment Kazumi Ikeda is my favourite. Even though there is nothing truly standout, the episodes where she is AD in always standout for… Read more »

Coincidentally, Nobuaki Maruki is serving as Chief Animation Director on Tsurune, the third show in a row where he’s working from Miku Kadowaki’s character designs. And Yasuhiro Takemoto is serving as Supervisor on Tsurune.

Wow, that was a dense and looonnnnnggg read, but I’m glad I finally made it through the whole thing! I learned so much and have even more respect for my favorite studio now. I should’ve expected it, but this is an even more incredible history than I could’ve imagined.

I actually had to leave out some stuff (more on all the subcontracted work they did like raito-kun did years ago, how their focus on young creators affects the studio dynamics) and got to skip some parts I’d covered in posts like Yamada’s, but yeeeaah it turns out a whole studio’s history can be pretty dense. I should have learned my lesson from when I did something similar regarding SHAFT and split it in different posts, but KyoAni stuff already sets off enough angry spammers as it is. No regrets about how it turned out though, glad you liked it!

I loved it. Don’t worry about the length either. Thankfully there is no rule saying people have to read an entire post in one sitting. lol

Hey Kevin, thanks for this amazing article! Just curious about KyoAni’s start, did Hatta Hideaki have any credits or did he work in anime in any capacity before KyoAni? From what I can gather from this (and a few other articles), it seems like Hatta Hideaki only got involved in anime after his wife Yoko started Kyoto Anime Studio and things grew bigger after that. It seemed strange to me that an anime artist would move to Kyoto if her husband was in anime as well, given that there didn’t seem to be much of an anime industry in Kyoto… Read more »

Yes, he only got involved with anime production after Yoko’s initiative began growing, so she was by all means the “culprit” behind this all! Sometimes it’s complicated to check this stuff since back then the idea that you should credit everyone involved in the production process wasn’t as established as it is now, even though back then it would have been much more feasible than with the current mess. In this case that’s not an issue though!

This is a fantastic and wonderful essay and thank you so much for all this hard work and research! I learned so much today <3

Nice article, can I translate it into Chinese and upload to BiliBili? I’ll put your name there I promise.

Sure, go ahead!

I have to confess, when I saw the title of the article I had a reaction along the lines of “Oh, yet another examination of Kyoani and how they’re so special. I totally haven’t seen this a hundred times before.” Now keep in mind that I do know Kyoani is unique, but sometimes I feel like their uniqueness is over-covered. My bias might play into that a bit also since I tend to find their works fairly unimpressive in terms of story despite my appreciation for their craft. Regardless though, I just wanted to say that this article pleasantly surprised… Read more »

Great informative post. Thanks for this.

I can feel the resentment towards Yamakan in this article, not that he doesn’t deserve to be hated, because honestly he kind of does.

I can add nothing of value, I just want to let you know how great of a write-up this is! Thanks so much!

The end of this post now feels real sad with what happened today

“What we know for a fact, though, is that unless a tragedy occurs it’ll still feel like Kyoto Animation: a team of creators who’s had a consistent vision for decades, one that they’ve stuck with through hardships and success.”

I cried at the last line. I truly hope this amazing studio can recover.

But now we know, even a tragedy occur, it still feel like Kyoto Animation

This was amazing! Sorry for this question, but could you please tell me what the first image is from? It looks like a shooting star? Thank you.

It’s from a short anime KyoAni made about their mascot. “Baja no Studio”.

I still can not believe that such a monstrous crime really happened. I didn’t just enjoy Koe no Katachi, Hyouka, Tamako and their adaptations of Key’s visual novels, this show literally became a part of my life. I … I find it difficult to find words to express my feelings at this moment.

Personally, I’d put this Tragedy on (at least) one Level with the Charlie Hebdo Massacre in Paris.

As far as I know, it’s said that the Man in Charge was supposedly an Ex-Employee of the Studio who felt robbed of personal Intellectual Property. Whatever the Outcome, I hope he gets/got what he deserves.

The final paragraph is haunting in light of the tragedy that has occurred ;-;. Best wishes to KyoAni, the survivors, the families of those who passed away, and everyone else directly connected. I truly hope the studio can recover from this monstrous attrocity.

It is a shame that they weren’t the ones to animate Full Metal Panic: Invisible Victory. The one Xebec made was truly awful.

Pray for Kyoto animation